If true, am I really a “leader”?

If I choose to shirk responsibility, what am I?

If I choose to…

…say “just give it to me” instead of teach,

…set a low standard so I don’t have to teach,

…blame them for not “being better”,

…blame them for my anger instead of owning it,

…let the outcome we’re trying to achieve remain unclear,

…keep the important reason for what we’re doing a secret,

…leave my own behavior unmeasured and unmanaged,

…set a high standard without being willing to teach,

…proceed without listening to what’s really going on,

…proceed without understanding their superpowers and motivations,

…withhold my true feelings about a problem,

…avoid difficult conversations,

…believe doing gopher work to help the team is “beneath me”,

…steal loyalty by threatening shame or embarrassment,

…move around 1 on 1 time when I get better plans,

…be absent in a time of need (or a time of quiet celebration),

…waffle on a decision,

…or let a known problem fester,

Am I really a “manager” or a “leader”? Can I really call myself a “parent”?

If I’ve shirked all the parts requiring responsibility, what am I?

To me all “leadership” really is, is taking responsibility. It’s the necessary and sufficient condition of it. The listed items I’ve prepared are just some examples of the responsibilities we can choose (or not) to take.

And, definitely, there are about 5 of those that I fail at, regularly. My hope is that by making these moments transparent, it will be more possible to make different choices.

The Great Choice

The greatest of all choices is choosing whether or not to be a good person.

In the spring of 2012, my life was a mess - even though it didn't appear that way to almost everyone, even me. But a few people did realize I was struggling, and that literally changed the trajectory of my life. It was just a little act, noticing, that mattered. And from noticing, care. Those seemingly small acts were a nudge, I suppose, that put me back on the long path I was walking down, before I was able to drift indefinitely in the direction of a man I didn’t want to become.

Those small acts of noticing and care were acts of gracious love, that probably prevented me from squandering years of my life. Without a nudge, it might have been years before I had realized that I lost myself. Because in the spring of 2012, I was making the worst kind of bad choices – the ones I didn’t even know were bad.

But I’m getting ahead of myself here.

Trying to become a good person is like taking a long walk in the woods. It’s winding. It’s strenuous. It’s not always well marked and there are a lot of diversions. There’s also, as it turns out, not a clear destination. Being a good person is not really a place at which we arrive, and then just declare we’re a good person. It’s just a long walk in the woods that we just keep doing – one foot in front of the other.

It is not something we do because it is fun. A long walk in the woods can be chilly, rainy, uncomfortable – not every day is sunny.

Righteousness is a word that I learned at an oddly young age. I must have been 10 or younger, I think. It was a world I heard lots of Indian Aunty’s and Uncles say during Swadhyaya, which is Sanskrit for “self-study” and what my Sunday school for Indian kids was called that I went to as a boy. And when those Auntys and Uncles would teach us prayers and commandments and the like – righteousness was a word that was often translated.

My father also used that word, righteous. I can hear him, still, with his particular pronunciation of the word talking to me about the rite-chus path. This idea of taking a long walk in the woods, you see boys, is an old idea in our culture. To me, talking about being a good person, going on a long walk in the woods, taking the righteous path – whatever you want to call it – are not just words and metaphors. It’s a dharma – a spiritual duty. It’s a long walk down an often difficult, but righteous, path.

But it is still a choice. Will we take the long walk?

This is a choice to you, like it was to me, my father before me, and his father before he. All of your aunts and uncles, grandparents, had this choice. In our family, this is a choice we have had to make – will we walk the righteous path or not? Will we do the right thing, or not? Will we take the long walk, day after day, or will we not? Will we try to be good people, or will we not?

This is the great choice of our lives. We have to choose.

This passage is from a book I’ve drafted and am currently editing. To learn more and sign up to receive updates / excerpts click here.

We Need To Understand Our Superpowers

We need to take the time to understand our superpowers, as individuals or as an organization, so we have the best chance to create surplus.

Surplus is created when something is more valuable than it costs in resources. Creating surplus is one of the keys to peace and prosperity.

Surplus ultimately comes from asymmetry. Asymmetry, briefly put, is when we have something in a disproportionately valuable quantity, relative to the average. This assymetry gives us leverage to make a disproportionally impactful contribution, and that creates surplus.

Let’s take the example of a baker, though this framework could apply to public service or family life. Some asymmetries, unfortunately, have a darker side.

Asymmetry of…

…capability is having the knowledge or skills to do something that others can’t (e.g., making sourdough bread vs. regular wheat).

…information gives the ability to make better decisions than others (e.g., knowing who sells the highest quality wheat at the best price).

…trust is having the integrity and reputation that creates loyalty and collaboration (e.g., 30 years of consistency prevents a customer from trying the latest fad from a competitor).

…leadership is the ability to build a team and utilize talent in a way that creates something larger than it’s parts (e.g., building a team that creates the best cafe in town).

…relationships create opportunities that others cannot replicate (e.g., my best customers introduce me to their brother who want to carry my bread in their network of 100 grocery stores).

…empathy is having the deep understanding of customers and their problems, which lead to innovations (e.g., slicing bread instead of selling it whole).

…capital is having the assets to scale that others can’t match (e.g., I have the money to buy machines which let me grind wheat into flour, reducing costs and increasing freshness).

…power is the ability to bend the rules in my favor (e.g., I get the city council to ban imports of bread into our town).

…status is having the cultural cachet to gain incremental influence without having to create any additional value (e.g., I’m a man so people might take me more seriously).

We need to understand our superpowers

So one of the most valuable things we can do in organizational life is knowing the superpowers which give us assymetry and doing something special with them. We need to take the time to understand our superpowers, as individuals or as an organization, so we have the best chance to create surplus.

And once we have surplus - whether in the form of time, energy, trust, profit, or other resources - we can do something with it. We can turn it into leisure or we can reinvest it in ourselves, our families, our communities, and our planet.

—

Addendum for the management / strategy nerds out there: To put a finer point on this, we also need to understand how asymmetries are changing. For example, capital is easier to access (or less critical) than it was before. For example, I don’t know how to write HTML nor do I have any specialized servers that help me run this website. Squarespace does that for me for a small fee every month. So access to capital assets and capabilities is less asymmetric than 25 years ago, at least in the domain of web publishing.

As the world changes, so does the landscape of asymmetries, which is why we often have to reinvent ourselves.

There’s a great podcast episode on The Knowledge Project where the guest, Kunal Shah, has a brief interlude on information asymmetry. Was definitely an inspiration for this post.

Source: Miguel Bruna on Unsplash

“Friends of friends are all friends”

Being part of a collective story is a very special type of human experience that brings a deep, grounded, and peace-giving joy.

“Friends of friends are all friends”

This is one of the enduring bits of wisdom my friend Wyman has taught me. And sure enough, at the friends’ night the evening before his wedding, we were, indeed, all friends.

This has been the case at the weddings and bachelor parties I’ve been to over the years. I get along swimmingly, without fail, with the friends of my closest friends. And the most fun I’ve had at weddings are usually preluded by an energizing, seemingly providential, friends night. This has been a pattern, not a coincidence.

I think the underlying cause of this is stories, and how we want to be part of stories that matter.

Weddings are great examples of stories that matter. Robyn and I still talk often about stories from our own wedding.

Like the bobbing poster sized cutouts of our heads that our friends Nick and Liz found and the heat it brought to an already sizzling dance floor. We remember the quick stop we had at Atwater brewery for post-ceremony photos, that our entire family showed up at, and the pints of Whango we had to chug on our way to our wedding reception. And I’ve learned to laugh about how my very best friends let me get locked in the church after our wedding rehearsal.

But just as often, we reminisce over the stories of other weddings we’ve attended, where we were just part of the supporting cast, rather than the protagonists.

We remember how we scurried across Northern California to attend a Bay Area and Tahoe wedding in the same weekend. We remember the picnic in a Greenville park and how we climbed a literal mountain for the marriage of Robyn’s closest childhood friend. We relive trips to places like Grand Rapids, Chicago, and Milwaukee and the adventures we’ve had with old friends we reconnected with at destinations across the country.

Weddings are more than just significant, however. They are also collective stories, where the narrative is made from the interwoven threads of an ensemble cast, rather than a single strand dominated by the actions of one person. The bride and groom may be the protagonists, but for a wedding the rest of the ensemble and the setting is just as important. That everyone can be part of the story is exactly the point.

All the best stories, I think, are collective, ensemble tales. The story of a wedding. The novel East of Eden. The story of my family. The story of America. The stories of scripture. The story of a championship athletic teams. The stories of social movements to expand rights and freedoms all across the world. The story of Marvel’s Avengers. The story of great American cities like Detroit, New York, and Chicago. The story of a marriage. The story of our marriage.

These stories are all made up of interwoven threads and an ensemble cast, and that’s what make them transcendent. Collective stories have archetypes and themes that everyone understands, and that’s what makes them powerful and magnetic.

I think the deep yearning to become part of a meaningful, transcendent, collective story is why friends of friends become friends at weddings. The yearning opens our hearts and minds to new experiences and brings out the truest and purest versions of ourselves.

But more broadly than that, collective stories also explain why we see people making seemingly irrational and painful sacrifices for something larger than themselves. The desire to be part of a collective story drives people to do everything from serve their country, commit to a faith, travel thousands of miles to be home for the holidays, or take on a cause that others think is lost.

Being part of a collective story is a very special type of human experience that brings a deep, grounded, and peace-giving joy. Giving someone the chance to be a part of a story like that is one of the greatest gifts that can be given.

“Papa? Will you never die?”

What I need, desperately, is to be here.

“Papa? If you take good care of your body, will you never die?”

This was the last tension, that once revealed, unwound the bedtime tantrums a few nights ago. As it turns out, it wasn’t the imminent end of our annual extended family vacation in northern Michigan that had Bo’s feelings and stomach in knots.

It was death.

Unasked and unanswered questions about death. Doubts about death. Anxiety about death, so insidious that I have not a single clue how the questions were seeded in his mind and why they sprouted so soon.

“I want to be with you for a hundred million infinity years, Papa. A hundred million INFINITY.”

Such earnest, piercing, and deeply empathetic honesty is the fingerprint of our eldest son’s soul.

When he tells me this, my excuses all evaporate. How could I ever not eat right from this day forward? How could I ever get to drunkenness ever again? How can I not be disciplined about, exercise, sleep, and going to the doctor? How could I ever contemplate texting and driving, ever again? How could I let myself stress about something as artificial as a career? For Bo, for Robyn, and our two younger sons, how could I do anything else?

I needed to hear this, this week, because I have been losing focus on what really matters.

I have been moping about how I feel like many of my dreams are fading. My need to return to public service. My need to challenge the power structures that tax my talent everyday at work. The book I need to finish, or the businesses I need to start. Ego stuff.

In my head, at his bedside, my better angels turned the tide in the ongoing battle with my ambition. Those are not needs. Those are wants. To believe they are needs is a delusion. Dreams are important, yes, but they are wants, not needs.

All I really need, desperately, is to be here. To show up. To wake up with sound-enough mind and body. To not lose anyone before the next sunset. To have who and what I am intertwined with to stay intertwined. This is what I need.

What I vowed to Bo is that I would take care of my body, because I wanted to be here for a long, long, long, long, long, long time.

“I will be here for as long as I can. I want to be here, with you and our family, for as long as I can.”

And as he drifted to sleep, I stayed a moment, kneeling, and thought - loudly enough, only, perhaps, for his soul to overhear,

“Please, God, help us all be here for as long as we can.”

Measuring the American Dream

If you set the top 15 metrics, that the country committed to for several decades, what would they be?

In America, during elections, we talk a lot about policies. Which candidate is for this or against that, and so on.

But policies are not a vision for a country. Policies are tools for achieving the dream, not the American Dream itself. Policies are means, not ends.

I’m desperate for political leaders at every level - neighborhood, city, county, state, country, planet - to articulate a vision, a vivid description of the sort of community they want to create, rather than merely describing a set of policies during elections.

This is hard. I know because I’ve tried. Even at the neighborhood level, the level where I engage in politics, it’s hard to articulate a vision for what we want the neighborhood to look like, feel like, and be like 10-15 years from now.

Ideally, political leaders could describe this vision and what a typical day in the community would be like in excruciating detail, like a great novelist sets the scene at the beginning of a book to make the reader feel like they’ve transported into the text.

What are you envisioning an average Monday to be like in 2053? I need to feel it in my bones.

Admittedly, this is really hard. So what’s an alternative?

Metrics.

I’m a big fan of metrics to help run enterprises, because choosing what to measure makes teams get specific about their dreams and what they’re willing to sacrifice.

Imagine if the Congress and the White House came up with a non-partisan set of metrics that we were going to set targets for and measure progress against for decades at a time? That would provide the beginnings of a common vision across party, geography, and agency that everyone could focus on relentlessly.

This is the sort of government management I want, so I took a shot at it. If I was a player in setting the vision for the country, this would be a pretty close set of my top 15 metrics to measure and commit to making progress on as a country.

This was a challenging exercise, here are a few interesting learnings:

It’s hard to pick just 15. But it creates a lot of clarity. Setting a limit forces real talk and hard choices.

It pays to to be clever. If you go to narrow, you don’t have spillover effects. It’s more impactful to pick metrics that if solved, would have lots of other externalities and problems that would be solved along the way. For example, if we committed to reducing gun deaths, we’d necessarily have to make an impact in other areas, such as: community relationships, trust with law enforcement, healthcare costs, and access to mental health services.

You have to think about everybody. Making tough choices on metrics for everyone, makes the architect think about our common issues, needs, and dreams. It’s an exercise that can’t be finished unless it’s inclusive.

You have to think BIG. Metrics that are too narrow, are more easily hijacked by special interests. Metrics that are big, hairy, and audacious make it more difficult to politicize the metric and the target.

Setting up a scorecard, with current state measures and future targets would be a transformative exercise to do at any level of government: from neighborhood to state to nation to planet.

It’s not so important whether my metrics are “right” or if yours are, per se. What matters is we co-create the metrics and are committed to them.

Let’s do it.

“How do I become a good father?”

The question of how to raise good children starts with figuring out how to be a good person myself.

Let me be honest with you.

I don't know whether I'm a good man, whether I will be a good father, or even whether I'll ever have the capacity to know - in the moment, at least - whether I'm either of those things. I, nor anyone, will truly be able to judge whether I was a good father or a good man until decades after I pass on from this earth.

I do know, however, that is what I want and intend to be. I want to be a good father and the father you all need me to be.

Wanting to be a good father was my central objective in writing this book. The sentiment I had in the Spring of 2017, a few months before Bo was born, is the same sentiment I feel now – I want to be a good father, but I need to figure it out. I am not nervous to be a father, but I’m not sure I know how just yet. I am excited to be a father, but what would it mean to be a good one? What do I need to do? How do I actually do it? How do I actually walk the walk?

This book is my answer to this simple, fundamental, difficult question: how do I become a good father? In this letter and the letters that follow, my goal is to answer that question in the greatest rigor and with the most thoughtfulness I can. As you’ll see in the pages that follow, the answer to the question quickly becomes an inquiry on how I become a good person myself, because I need to walk the walk if I want you three to grow to become good people. As it turns out, the best way (and perhaps only way) I could adequately answer this question with the intensity and emotional labor it required was by talking with you all – my three sons – and writing to you directly. You boys are the intended audience of this volume of letters.

When I first started writing in 2017, your mother and I only knew of Robert’s pending birth, though we dreamed of you both, Myles, and Emmett. And by the grace of God, all three of you are here now as I begin rewrites of this manuscript in the spring of 2022, about three weeks after Emmett was born. Now that you three are here, I have edited this volume to address you all in these letters collectively, even though that wasn’t the case in my original draft.

At the beginning of this project, I wasn’t sure if I would share it with anyone but our family. But as I went, I started to believe that the ideas were relevant and worth sharing beyond our roof. This book become something I’ve always wanted from philosophers, but I felt was always missing. As comprehensive as moral philosophy and theology are with the question of “what” – what is good, what is the right choice, etc. – what I found lacking was the question of “how”. How do we actually become the sort of people that can actually do what is good? How do we actually become the sort of people that make the tough choices to live out and goodness in our thoughts and our actions? How do we actually learn to walk the walk?

This question of “how” is unglamorous, laborious, and pedantic to answer. It takes a special kind of zealotry to stick with, especially because it requires a tremendous amount of context setting and when you’re done all the work you’ve done seems so obvious, cliché even. And yet, the question of how – how we become good people is so essential.

Perhaps that’s why philosophers don’t seem to emphasize it, but parents and coaches do. Coming up with the “what” is sexy, cool, flashy, and novel and once you lay down the what, it’s easy to walk away and leave the details to the “lesser minds” in the room. On the contrary, you have to care deeply about a person to get into the muck of details to help them figure out “how” to do anything. Figuring out the how is a much longer, arduous, and entangled journey.

This passage is from a book I’ve drafted and am currently editing. To learn more and sign up to receive updates / excerpts click here.

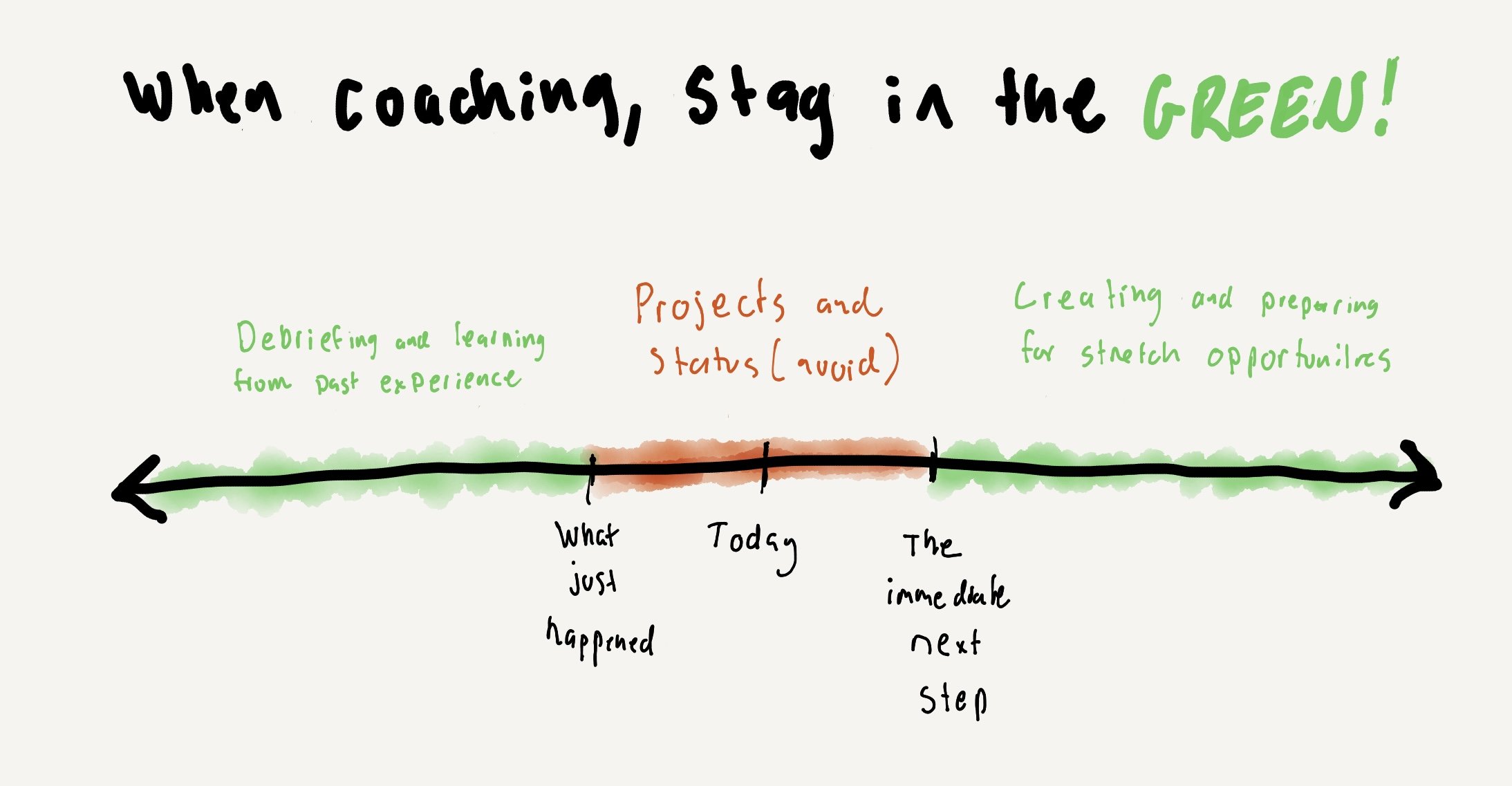

Coaching Requires Dedicated, intensely Focused Time

The biggest error of coaching - not being intentional about it - can be avoided by dedicating real time to it.

People develop faster when they are coached well, but coaching doesn’t happen without intent. To be a better coach, start with making actual “coaching time” that is intentional and intensely focused.

First, as a manager, we must dedicate one-to-one time with whomever we are trying to coach. 30 minutes per week, used well, is enough.

Second, that time can’t be about projects or status. It has to be spent on debriefing to glean learnings from past performance, or on how to create and prepare for future stretch opportunities.

Find a better way to manage status and project work than during a 1-1 and dedicate that time too and use it with intense focus. Personally, I like daily stand-ups from Agile/Scrum methodology and a once weekly full project review with the whole team.

Then, set a rule that during the dedicated time you will not talk about project status or the daily grind of work. If you dedicate time and hold firm to that rule, you’ll end up having a productive coaching conversation. Here are four questions that I’ve found work well to structure a 30-minute coaching conversation.

On a scale of 1 to 100, what percent of the impact you think you could be making are you actually making? (2-4 minutes)

Compared to last week, is your rate of growth accelerating, decelerating, or about the same? (2-4 minutes)

What do you want to talk about? (20-25 minutes)

What’s something I can do to help you feel respected and supported? (2-4 minutes)

This concept applies broadly: whether it’s coaching our team at work, our kids, our students, a volunteer group we’re part of, or co-coaching our marriage together with our partner, we must dedicate and focus the time. In my experience, the results of that dedicated time are exponential after just a few weeks.

Don’t Work Saturdays

Don’t waste the magic of Saturday mornings with work.

As a young twenty-something, I had a friend from work who told me one time that he went to great lengths to avoid working on Saturdays. It was some of the best advice I’ve ever received, and was provocative given that at the time both of us worked for a consultancy that required long hours and many of our colleagues bragged about how many hours they logged.

And what fortuitous advice to get from a peer at a such a formative time in my professional life. I started to avoid work on Saturdays and I still do. And thank God for that. Saturday mornings are a sacred time.

To some extent, I think I always knew this, or at least acted as if they were by accident.

If you grew up in the Midwest or went to college here, you know that our ritualistic observance and respect of Saturday mornings runs deep, and might as well be explained by “something in the water.” Because, after all, we have college football.

This observance and participation in the magic of saturday morning college football started when I was a pre-teen. I remember little of what happened when I was 10, except for the herculean Michigan team that won the National Championship. I still remember Charles Woodson, Brian Griese, and many of the key plays of that season. Every week I would get up, watch the pre-game show and then the game. That was that. No exceptions. Saturday mornings. That’s just what we do.

This continued, obviously, when I showed up for college in Ann Arbor and learned the true glory and glee of a collegian’s tailgate. When we lived in the fraternity house, we’d rally the brotherhood, and march down the street to a nearby sorority house - as if we were part of a parade - trays of Jell-O shots in hand. We’d then rouse the sorority sisters from sleep, with said Jell-O shots before continuing to the senior party house by the football stadium where the tailgate had already begun, and the streets had already started filling with sweatshirts and jerseys laden with maize and blue.

It’s absolutely magical, and for some borders on being a quasi-religious experience if you can believe that. Saturday mornings are a sacred time.

Buy Saturday morning magic extends far beyond football. There were the summers in Washington D.C., for example, where I interned every year of college. We lived in the George Washington University dorms, with about 50 other Michigan undergrads and the few others living down the halls from smaller schools that we’d adopted.

The morning would always start slow, and we’d have an invite for everyone to venture through our open door and brunch on some pancakes that my roommates and I had made, catching up about the latest stories made into zeitgeist by the The Washington Post, the pubs folks had visited the night before, the latest policy paper from a think tank making the rounds, or plans for sightseeing over the weekend.

As we’d wrap up shortly before noon, someone would inevitably bellow, with full throat and diaphragm through the dormitory corridors, “TTRRRRAAADDDERRRR JOOOOOOOOEEEESSS!”, which was our universally understood cry that someone was going grocery shopping and was looking for a friend to join them for round trip to and from the edge of Georgetown.

And that was that. That is just what we did, for no other reason than it being Saturday morning. Magical times.

I was reminded of the sacredness of Saturday mornings just yesterday. It was our first trip as a family of five to Eastern Market - Detroit’s largest farmer’s market, which is one of it’s crown jewels, rights of passage, and among the most illustrious and inclusive farmers markets in the country.

We strolled through shed-by-shed, perusing the day’s produce - me pushing the littler boys in the stroller and Robyn walking a few steps ahead with Bo, our 4-and-a-half year old. We grabbed a coffee, and worked our way back through the market’s sheds, stopping by a few farm stands that caught our eye for their fresh produce and attractive prices.

Then we stopped by the Art Park on our way a crepe stand for an early lunch, waiting patiently and with gentle smiles, because we were glad to just be there together. We didn’t care that it took a while, being slow was an opportunity, not an inconvenience.

This is what Saturday mornings are supposed to be like. If you ask me at least.

They’re not for moving fast, they’re for being uncharacteristically slow. They’re not for gearing up, they’re for gearing down. They’re not for hustling, or even for walking with a modicum of fierceness, they’re for ambling. They’re not for to-do-lists, they’re for togetherness and tradition. They’re not for working, they’re for everything but.

I am so grateful that someone set an example for me to not work on Saturday’s. It changed the course of my life, and I don’t think it’s hyperbolic to say that.At every phase of my life, with every community I’ve been part of, in every location I’ve ever lived, Saturday mornings have become magical, sacred times.

But none of that Saturday has a chance if we’re working - whether that’s emails, doing chores with tunnel vision, or otherwise doing something with the intention of being “productive.” We only have a few thousand of these Saturday mornings and it’s a tragedy to waste them.

Don’t work Saturdays.

Creating Safe and Welcoming Cultures

The two strategies - providing special attention and treating everyone consistently well - need to be in tension.

To help people feel safe and welcome within a family, team, organization, or community, two general strategies are: special attention and consistent treatment.

Examining the tension between those two strategies is a simple, powerful lens for understanding and improving culture.

The Strategies

The first strategy is to provide special attention.

Under this view, everyone is special and everyone gets a turn in the spotlight. Every type of person gets an awareness month or some sort of special appreciation day - nobody is left out. Everyone’s flag gets a turn to fly on the flag pole. The best of the best - whether it’s for performance, representing values, or going through adversity - are recognized. We shine a light on the bright spots, to shape behaviors and norms.

And for those that aren’t the best of the best, they get the equivalent of a paper plate award - we find something to recognize, because everyone has a bright spot if only we look.

This strategy works because special attention makes people feel seen and acknowledged. And when we feel seen, we feel like we belong and can be ourselves.

But providing special attention has tradeoffs, as is the case with all strategies.

The first is that someone is always slipping through the cracks. We never quite can neatly capture everyone in a category to provide them special attention. It’s really hard to create a recognition day, for example, for every type of group in society. Lots of people live on the edges of groups and they are left out. When someone feels left out, the safe, welcoming culture we intended is never fully forged and rivalries form.

The second trade off is that special attention has diminishing marginal returns. The more ways we provide special attention, the less “special” that attention feels. Did you know, for example, that on June 4th (the day I’m writing this post) is National Old Maid’s day, National Corgi Day, and part of National Fishing and Boating week, plus many more? Outside of the big days like Mother’s Day and Father’s Day - how can someone possible feel seen and special if the identity they care about is obscure and celebrated on a recognition day that nobody even knows exists?

The existence of “National Old Maid’s day” is obviously a narrow example, but it illustrates a broader point: the shine of special attention wears off the more you do it, which leads to the more obscure folks in the community feeling less special and less visible, which breeds resentment.

The second strategy to create a feeling of safety and welcoming in a community is to treat everyone consistently well.

In this world everyone is treated fairly and with respect. Every interaction that happens in the community is fair, consistent, and kind. We don’t treat anyone with boastful attention, but we don’t demean anyone either. We have a high standard of honesty, integrity, and compassion that we apply consistently to every person we encounter..

The most powerful and elite don’t get special privileges - everyone in the family only gets one cookie and only after finishing dinner, the executives and the employees all get the same selection of coffee and lunch in the cafeteria, and we either celebrate the birthday of everyone on the team with cake or we celebrate nobody at all.

The strategy of treating everyone consistently well works because fairness and kindness makes people feel safe. When we’re in communities that behave consistently, the fear of being surprised with abuse fades away because our expectations and our reality are one, and we know that we will be treated fairly no matter who we are.

But this strategy of treating other consistently well also has two tradeoffs.

The first, is that it’s really hard. The level of empathy and humility required to treat everyone consistently well is enormous. The most powerful in a group have to basically relinquish the power and privilege of their social standing, which is uncommon. The boss, for example, has to be willing to give up the corner office and as parent’s we can’t say things like “the rules don’t apply to grown ups.” A culture of consistently well, needs leadership at every level and on every block. To pull that off is not only hard, it takes a long time and a lot of sacrifice.

The second tradeoff is that to create a culture of consistently well there are no days off. For a culture of consistently well to stick, it has to be, well, consistent. There are no cheat days where the big dog in the group is allowed to treat people like garbage. There are no exceptions to the idea of everyone treated fairly and with respect - it doesn’t matter if you don’t like them or they are weird. There is no such thing as a culture of treating people consistently well if it’s not 24/7/365.

The Tension

The answer to the question, “Well, which strategy should I use?” Is obvious: both. The problem is, the two approaches are in tension with each other. Providing special attention makes it harder to treat others consistently and vice versa. They key is to put the two strategies into play and let them moderate each other.

A good first step is to use the lenses of the two strategies to examine current practices:

Who is given special attention? Who is not?

Who doesn’t fit neatly into a category of identity or function? Who’s at risk of slipping through the cracks?

What do our practices around special attention say about who we are? Are those implicit value statements reflective of who we want to be?

What are the customs that are commonplace? How do we greet, communicate, and criticize each other?

Who is treated well? Who isn’t? Are differences in treatment justified?

How do the people with the most authority and status behave? Is it consistent? is it fair?

What are the processes and practices that affect people’s lives and feelings the most (e.g., hiring, firing, promotion, access to training)? Are those processes consistent? Are they fair? Do they live up to our highest ideals?

As I said, the real key is to utilize both strategies and think of them as a sort of check and balance on each other - special attention prevents consistency from creating homogeneity and consistency prevents special attention from becoming unfairly distributed.

From my observation, however, is that most organizations do not utilize these strategies in the appropriate balance. Usually, it’s because of an over-reliance on the strategy of providing special attention. That imbalance worries me.

I do understand why it happens. Providing special attention feels good to give and to receive and is tangible. It’s easy to deploy a recognition program or plan an appreciation day quickly. And most of all, speical attention strategies are scalable and have the potential to have huge reach if they “go viral.”

What I worry about is the overuse of special attention strategies and the negative externalities that creates. For example, all the special appreciation days and awareness months can feel like an arms race, at least to me. And, I personally feel the resentment that comes with slipping through the cracks and see that resentment in others, too.

Excessive praise and recognition makes me (and my kids, I think) into praise-hungry, externally-driven people. The ability to have likes on a post leads to a life of “doing it for the gram”. The externalities are real, and show up within families, teams, organizations, and communities.

At the same, I know it would be impractical and ineffective to focus one-dimensionally on creating cultures of consistently well. It’s important that we celebrate differences because we need to ensure our thoughts and communities stay diverse so we can solve complex problems. I worry that just creating a dominant culture without special attention, even one that’s rooted on the idea of treating people consistently well, would ultimately lead to homogeneity of perspective, values, skills, and ideologies instead of diversity.

The solution here is the paradoxical one, we can’t just utilize special attention or treating people consistently well to create safe and welcoming communities - we need to do both at the same time. Even though difficult, navigating this tension is well worth it because creating a family, team, organization, or community that feels safe and welcoming is a big deal. We can be our best selves, do our best work, and contribute the fullest extent of our talents when we feel psychological safety.

We All React To Feeling Invisible

I believe that we all feel invisible, to some degree. How we react to that perceived invisibility is an important choice.

Most of the time I feel invisible.

This is mostly because of my three most salient social identities: Indian-American, Man, and Father.

Being Indian in America is like being in purgatory. On the one hand, most people assume I am a physician or in IT and I rarely feel racially profiled by the police, the courts, or other tentacles of the state. Most of the time, in most places, I don’t feel predisposed to racial slurs or ethnic violence. It’s not, hard, per se.

On the other hand, I’ve been told so many times “thanks for herding the cats” instead of “thank you for your leadership.” So many times, people have assumed my parents are stupid because of their accent or seem surprised that I like country music and hip-hop or that I married a white woman.

So many times, people at work have made me work harder and prove more than any of my counterparts for the same opportunities. And, there is no recognized constituency, politically speaking, for Indian-Americans because we’re a small percentage of the population and we’re disproportionally wealthy - I don’t get the sense that anybody feels like we need support. Being Indian is not, easy, per se, either.

I also feel like an outcast among men, because I never feel like I relate to “men.” My interests are different and would probably be considered feminine if anyone was keeping track. I’ve never been able to build muscle mass lifting weights and I don’t like violence, aggression, sarcasm, or sexual humor. I don’t want to play fantasy football or golf, nor do I want to.

I am also a father. And these days its en vouge to make hapless fathers into the butt of jokes. And, in the workplace fathers get no sympathy and have no champions because a lot of time, it seems, than men aren’t allowed to be championed - even dads trying to figure it out.

Yes, I feel invisible. But the truth is, I honestly believe that everyone feels invisible or treated unfairly - even white men - at least sometimes. And I think that’s true - I don’t think anyone is ever treated as fairly as they should be - even white men. We live in a country with low levels of trust so I think we should expect that everyone feels some degree of invisibility, too.

So in truth, we all have a choice to make - how will we react to our perceived invisibility?

There are four options.

I have thought about assimilating. For me, that usually means acting more like a white male, but for others assimilation might mean something different obviously. It’s just easier to be like everyone else. With assimilation it’s a tradeoff between invisibility and authenticity.

I have thought about just letting myself fade away and become more invisible. Not having a public life. Avoiding conflict. Just going through the motions, keeping to myself, and just riding out my days with close friends and family. Even if I’m invisible to the rest of the world, maybe there are a few dozen people who will see me for who I am. But, then, I will have lived an apathetic life. By letting myself become invisible, I would have to resign myself to not making the world a better place - because who can improve the culture we swim in if they don’t engage with it? With fading away, it’s a tradeoff between invisibility and contribution.

I have thought about aligning with a tribe. Maybe I lean more into attending the University of Michigan, a famous college. Maybe I do more “Indian Stuff” or join more “Indian people groups.” Or maybe, I just get more into professional sports and wear logo’d baseball caps more often.

But “aligning with a tribe” is basically a socially acceptable way of saying, “I’m going to join a gang.” The group identify of a “tribe” offers protection, just like a gang - it’s just social protection rather than physical. And the problem with being part of a gang iis that you usually have to be an enemy of a rival gang and prove loyalty to the group…somehow. With tribes, it’s a trade offs between invisibility and conflict.

Again, at some level, I think this is a choice we all face. How will we react to our perceived invisibility? Will we assimilate, fade away, or align with a tribe?

I can’t bring myself to do any of these things. I just can’t.

I’ve assimilated enough, already. I want to contribute rather than fade into the background. I don’t want to become less invisible at the cost of being an enemy of someone else. And so the implied fourth choice is “none of the above.” It is a long hard walk - that leaves me feeling, angry, overwhelmed, and lonely.

How will we react to our perceived invisibility? It’s choices like these that reveal true character and demonstrate its importance. There are few choices, too, I think, that are more difficult and more consequential.

Good Managers Produce Exceptional Teams

This is an OKR-based model to define what a good manager actually produces. It’s hard to be good at something without beginning with the end in mind, after all.

The difference between a good manager and a bad one can be huge.

Good managers make careers while others break them. Good managers bring new innovations to customers while others quit. Good managers find a way to make a profit without polluting, exploiting, or cheating while others cut corners. Good managers find ways to adapt their organizations while others in the industry go extinct.

But it’s almost impossible to be good at something without defining what success looks like. As the saying goes, “begin with the end in mind.”

This is one model for the results a good manager takes responsibility to produce.

What would you add, subtract, or revise? My hope is that by sharing, all of us that are committed to being good managers get better faster.

Objective: Be a Good Manager

Key Results:

Talent of each team member is fully utilized

Develop team members enough to be promoted

Team has and utilizes diverse perspectives

Team delivers measurable results on an important business objective

Team is trusted by internal and external customers

Team and all stakeholders are clear on on the why, what, how, when, and intended result of our work

Whole team feels supported and respected

Team stewards resources (time, money, etc.) effectively

We are reimagining what it means to be a man

There are men that are trying to reimagine what it means to be a man. As in, how to be a different and hopefully better kind of man.

And we are doing this without role models to draw from. We are breaking ground, and it is remarkable.

In the age we live in, what it means to be a man is being completely reimagined. And as a result, what we are trying to do as men - particularly as husbands, fathers, and citizens - is nothing short of remarkable. We are actively reinventing, for the first time, the role of men in society.

I struggle a lot with this.

On the one hand, I am a man. Being a man is a salient part of who I am and how I view the world. This may indicate, to some at least, that I’m less evolved and not as “woke”, if that’s the right word, than others among us. I’m not able to hold a world view that gender is entirely a social construction or that we should create a world that ignores the very concept of “men”. I’m not entirely sure what being a feminist or male ally entails, but I’m pretty sure I’m not that, exactly, either.

At the same time, I reject what being a man means today. And I’m not comfortable with the grotesque baggage that being a man is inseparable from. The criticisms of men and masculinity are legitimate, and that’s an understatement.

Men have controlled and abused women, for most of known history it seems - whether it was politically or through sexual violence. Marriages between men and women, generally speaking, have not be fair or equitable, ever. The glass ceiling is real - I see my women and my female colleague hindered and treated outright badly, in ways that men aren’t. I don’t want to be that kind of man.

But it seems to me, that for the first time, at least some men are trying to take on this tension - identifying with being a man, but rejecting its harmful externalities - and act differently. I don’t know if it’s a majority of men or even that a lot that are trying to reimagine what it means to be a man, but I’m certainly struggling through this tension. So are a lot of my friends and colleagues and it’s something we talk about. So it can’t be an immaterial amount of men who are trying to figure this out, right?

I love the mental model of using an OKR (Objective and Key Results) to set clear goals (you can get a nice crash course on OKRs, here). And so I tried applying it to “being a good man” - this is what being a “good man” means to me:

When I was done, I had a “whoa” moment. The OKR I created, I realized, is quite different than what I would assume the stereotypical man of the 20th century would create if he were doing the same exercise. Hell, it’s quite different than what my own father would probably create. Like, can you imagine the men of 1950s sitcoms (or even 1990s sitcoms) talking about fair distribution of domestic responsibilities or parenting without fear tactics?

I can’t. Most of the protagonists in those shows had wives who didn’t work outside the homes - the contexts in which those characters were cast is wildly different than our own.

And that’s what makes what we’re doing remarkable. We’re trying to envision a different future - and live it ourselves - without having any sort of role model on what this reconception of what it means to be a man can look like. It’s even more remarkable and complex because it’s not just heterosexual men in same-race relationships that are figuring this out. Gay men and men in interracial or interfaith relationships are also figuring out how to be husbands, fathers, and citizens in this time of cultural flux around what it means to be a man.

I couldn’t talk to my own father about this anyway (God rest his soul), but even if he was around he couldn’t be my role model for this journey. Despite my father being the most honest and perhaps the kindest man I’ve ever met, he was still swimming in a culture with remarkably rigid gender roles. All our male role models were, because that was the culture of the times.

But beyond our own uncles, fathers, and grandparents, we don’t have stories in our culture to draw from for role models, either. There aren’t novels with strong, male protagonists that are trying to redefine manhood in the 21st century, that I’ve found at least. On the contrary, every novel I’ve heard my friends talk about with male protagonists were from detective novels, historical fiction, thrillers, or from science fiction - hardly relatable to men trying to recast their male identities.

There are great male role models from the canon of 20th century literature and culture - Atticus Finch of To Kill a Mockingbird, Aragorn from Lord of the Rings, Reverend John Ames from Gilead, or even Master Yoda from Star Wars are favorites of mine - but those characters are in the wrong context to really help us navigate the process of reimagine manhood as well. Atticus and Yoda are not really dealing with contemporary circumstances, obviously, as much as I really am inspired by their example.

Honestly, it seems like the Marvel Cinematic Universe and its superheroes going through real struggles and making real sacrifices are the closest role models we can look to as men trying to be better men. Maybe that’s why I like those films so much. But it’s hard and probably ego-inflating for me to relate to comic book superheroes. We need, and have to have something better than Marvel movies, right?

My wife loves the titles from Reese Witherspoon’s book club, and I honestly love hearing the stories of the novels she’s reading. All the titles are written by women and have strong female protagonists. I would love to have a similar book club, but with strong male protagonists trying to reimagine what it means to be a man. But what novels do we even have to choose from?

So fellas, what we are trying to do is remarkable. We’re not trying to navigate to a new place, as much as we’re trying to make a map to a place that’s never been visited.

We need to talk about it, blog about it, and podcast about it. Some of us have to write novels about it, or make music and movies about it. We have to leave a body of work for the next generation of men to draw upon. We have to leave our sons, nephews, students, players, and grandsons a place to start as they continue this remarkable journey of reimagining manhood that we’ve started.

To build a great team, get specific

To scale impact, every team leader has to build their team. Building a team is hard, but it’s not complicated.

To set us up for success, they key thing to do is get specific about the role, and the top 2-3 things we can’t compromise on in a candidate.

Building a team is hard, but it doesn’t have to be complicated.

What I’ve learned when trying to build teams (whether serving on hiring committees, recruiting fraternity pledges, or volunteer board members) is that most of the time we’re not specific enough.

To build a great team, we can’t just fill the role with a body. We can’t count on the perfect candidate either - there are no unicorns. Instead, we should be clear about the role, and the attributes that we can and cannot compromise on.

Here’s a video with a tool / mental model on how to actually do that.

Learning to Win Ugly

Learning how to win ugly is an essential skill. And yet, I feel like the world has conspired to keep me from learning it.

What it takes to “win” is different than what it takes to “win ugly.” In sports what it means to win ugly can be something like:

Winning a close, physical game

Winning in bad weather or difficult conditions

Winning without superstars

Winning after overcoming a deficit or when your team is particularly outmatched

Winning by just doing what needs to be done, even if it’s not fancy or flashy

But winning ugly is also a useful metaphor outside sports:

In a marriage: keeping a relationship alive during adversity (e.g., during a global pandemic) or after a major loss

In parenting: staying patient during bedtime when a child is overtired and throwing a tantrum

In public service: improving across-the-board quality of life for citizens after the city government, which has been under-invested in for decades, goes through bankruptcy (I’m biased because I worked in it, but the Duggan Administration Detroit is my thinly veiled example here)

At work: finding a way to reinvent an old-school company that’s not large, prestigious, or cash-infused enough to simply buy “elite” talent

The point of all these examples is to suggest that it’s easier to succeed when circumstances are good, such as when: there’s no adversity, the problem and solution are well understood, you’re on a team of superstars, or you’re flush with cash. It’s something quite different to succeed when the terrain is treacherous.

I’ve been thinking about the idea of winning ugly lately because as a parent, the fee wins we’ve had lately have been ugly ones.

Generally speaking, I’ve come to believe that winning ugly is important because it seems like when the stakes are highest and failure is not an option - like during a global pandemic, or when a city has unprecedented levels of violent crime, or when the economy is in free fall, or a family is on the verge of collapse after a tragedy - there’s usually no way to win except winning ugly.

I’d even say winning ugly is essential - because every team, family, company, and community falls upon hard times. In the medium to long run, it’s guaranteed. But honestly, I don’t think most people look at this capability when assessing talent for someone they’re interviewing for a job, or even when filling out their NCAA bracket.

Moreover, as I’ve reflected on it, I’ve realized that my whole life, I’ve been coached, actively, to avoid ugly situations. I was sent to lots of enrichment classes where I had a lot of teachers and extra help to learn things (not ugly). I had easy access to great facilities, like tennis courts, classrooms, computer labs, and weight rooms (not ugly). I was encouraged to take prep classes for standardized tests (not ugly). I was raised to think that the way to achieve dreams was to attend an Ivy League school (not ugly).

If I did all these things I could get a job at a prestigious firm that was established, and make a lot of money, and live a successful life.

What I’ve realized, is that this suburban middle class dream depends on putting yourself in ideal situations. The whole strategy hinges on positioning - you work hard and invest a lot so you can position yourself for the next opportunity. If you’re in a good position, you’re more likely to succeed, and therefore set yourself up for the next thing, and so on.

If you don’t think winning ugly matters, this is no problem. But if you do believe it’s important to know how to pull through when it’s tough, the problem is that the way you learn to win ugly is to put yourself into tough situations, not easy ones. The problem with how I (and many of us) were raised is that we didn’t have a lot of chances to learn to win ugly.

I, for example, learned to win ugly in city government, at the Detroit Police Department…in my late twenties and thirties.

There, we caught no breaks. Every single improvement in crime levels we had to scrap for. Every success seemed to come with at least 2 or 3 obstacles to overcome. We didn’t have slush fund of cash for new projects. We didn’t have a ton of staff - even my commanding officers had to get in the weeds on reviewing press briefings, grant applications, or showing up to crime scenes. Just about any improvement I was part of was winning ugly.

By my observation here’s what people who know how to win ugly do different:

No work is beneath anyone: if you’re winning ugly, even the highest ranking person does the unglamourous work sometimes. You can’t win ugly unless every single person on the team is willing to roll up their sleeves and do the quintessential acts of diving for loose balls, grabbing the coffee, sweeping the floor, or fixing the copy machine.

Unleashing superpowers: If you are trying to win ugly, that means you have to squeeze every last bit of talent and effort out of your team. That requires knowing your team and finding ways to match the mission with the hidden skills that they aren’t using that can bring disproportionate results. People who win ugly doesn’t just look for hidden talents, they look for superpowers and bend over backwards to unleash them.

Discomfort with ambiguity: A lot of MBA-types talk about how it’s important to be “comfortable with ambiguity”. That’s okay when you have a lot of resources and time. But that doesn’t work if you’re trying to win ugly. Rather, you move to create clarity as quickly as possible so that the team doesn’t waste the limited time or resources you have.

Pivot hard while staying the course: When you’re winning ugly, you can’t stick with bad plans for very long. People who have won ugly know that you don’t throw good money after bad, and you change course - hard if you need to - once you have a strong inclination that the mission will fail. At the same time, winning ugly means sticking with the game plan that you know will work and driving people to execute it relentlessly. Winning ugly requires navigating this paradox of extreme adjustment and extreme persistence.

Tap into deep purpose: Winning ugly is not fun. In fact, it sucks. It’s really hard and it’s really uncomfortable. Only people who love punishment would opt to win ugly, 99% of the time you win ugly because there’s no other way. Because of this reality, to win ugly you have to have access an unshakeable, core-to-the-soul, type or purpose. You have to have deep convictions for the mission and make them tremendously explicit to everyone on the team. That’s the only way to keep the team focused and motivated to persist through the absolute garbage you have to sometimes walk through to win ugly. Teams don’t push to win when it’s ugly if their motivation is fickle.

Doing the unorthodox: People who can win pretty have the luxury of doing what’s already been done. People who win ugly don’t just embrace doing unconventional things, they know they have no other choice.

Be Unflappable: I’ve listed this list because it’s fairly obvious. When it’s a chaotic environment, people who know how to win ugly stay calm even when they move with tremendous velocity. This doesn’t necessarily mean they don’t get angry. In my experience, winning ugly often involves a lot of cursing and heated discussions. But not excuses.

Sure, I think it’s possible to use this mental model when forming a team or even when interviewing to fill a job: someone may have a lot of success, but can they win ugly?

But more than that, I am my own audience when writing this piece. I don’t want to be the sort of husband, father, citizen, or professional that only succeeds because of positioning. At the end of my life, I don’t want to think of myself as someone who only succeeded because I avoided important problems that were hard.

And, I don’t want to teach our sons to win by positioning. I want them to succeed and reach their dreams, yes, but I don’t want to take away their opportunity to build inner-strength, either. This is perhaps the most difficult paradox of parenting (and coaching at work) that I’ve experienced: wanting our kids (or the people we coach) to have success and have upward mobility, but also letting them struggle and fail so they can learn from it, and win ugly the next time.

Dealing With it When Our Kids Act Ungratefully

I don’t want to make noise about the sacrifices I’ve made, but I don’t want my sacrifices to be insulted by ungrateful children. I don’t want my children feel deep shame or know intense suffering, but I also want them to have opportunities to build inner strength. In some ways I need to tell stories about sacrifice, but in other ways that’s counterproductive.

What’s a parent to do?

My most guttural resentment comes when sacrifices are insulted. These moments, when an unrestrained, vindictive, anger emerges from my otherwise even temperament are also when I’m most ashamed as a father.

This weekend, I have been angry so many times I have a lingering headache as I’m penning this entry. I’m lost my temper, so many times this weekend, despite it being the first beautiful weekend of the season and we haven’t had any adversity or hardship.

It goes like this.

One of our big kids will just do something mean, either to me, Robyn, or his brother. And then, I feel such acidic resentment.

I did not skip my shower today so you could pour soap onto the carpet during your nap. I did not go out of my way to buy a coconut at the grocery at your request so you could spit on the floor or on me. I did not quit a job I liked, was proud of, and found meaning in so you could throw magnet tiles at me or punch me in the privates…I actually did it so I could be a more present father to YOU.

Your mother did not work diligently to create a part time work schedule so you could intentionally pull your brother off a balance bike on our family walk. Three off your grandparents did not leave their home countries in search of a better life so you two could terrorize each other or deliberately destroy books in front of my face because you know it makes me angry. Are you not grateful? Do you know how good you have it?

It’s damning. It hurts so badly and makes me so angry when my sons - or anyone really - takes the sacrifices I’ve made, the sacrifices that I’m trying to make quietly and keep quiet, and throws them back in my face. It’s insulting, infuriating, and maddeningly saddening.

My sons don’t realize any of this, of course. They don’t realize the gravity of the sacrifices that their parents, grandparents, and great-grandparents have made so they could live the life they have. Hell, I didn’t get it at their age and probably don’t fully comprehend the degree of my ancestors’ sacrifices, even now.

Most of the time, I don’t want to tell them either. I, nor my parents and grandparents, made sacrifices in our lives to be able to tell great stories about ourselves and seek the applause of others.

I wouldn’t want my sons to feel some deep shame about their fortunate circumstances, either. After all, it’s not their fault they were born into a loving and prosperous family. And, I don’t want them to have to know what it feels like to be broke and wondering whether our family will lose our house. So yes, I don’t want to throw the sacrifices I’ve made in their face - spiking the football is not what we do, so to speak.

At the same time, hearing stories of my parents sacrifice - especially from others - gave me a halo of sorts. I felt so loved and so compelled to honor their sacrifice by working hard and not taking it for granted. It’s part of being the children of immigrants - when we hear about the sacrifices of our parents and ancestors it is a unique kind of affirming love, that motivates us to try to be better and to not let their sacrifice be squandered. Honoring their sacrifice, builds confidence and inner strength.

I often worry about this at a societal level.

Every person knows, deep down, I think that the most celebrated people on earth; the people who are loved, respected, and admired are not really exalted because of their accomplishments. They are lauded because of their sacrifices. This is as true for common people as it is for celebrities.

Maybe it’s just me, but I feel like our species has this radar and fascination with people who make sacrifices for something larger than themselves. We don’t, after all, tend to celebrate people who are born rich or with some sort of advantage from genetics or birthright. We celebrate people who work hard and make huge sacrifices to contributed whatever it is that they’ve contributed. We may fixate and envy the successes of others, but we don’t revere the successes themselves. We revere those individuals’ capability for sacrifice.

Making sacrifices builds character and confidence. If I can make a sacrifice for something bigger than myself, if I can endure suffering. If I can persist for the greater good, if can do deed cut from this cloth of sacrifice, I have proven my inner strength. Nobody else has to know it, so long as I know it.

Unfortunately, the opposite is also true. If I haven’t made sacrifices, I also know that. I know that I am untested. I know my inner strength is unproven. I know that I might be weak. And that’s a devastating, absolute lead balloon for building confidence. And I would imagine that lack of confidence and inner strength has to be compensated for somehow. If I know I am weak on the inside, I have to make up for it with my outward presentation to the world.

At a societal level, I think this has huge consequences.

Imagine if one generation of parents made big sacrifices during their lifetime and prepared them to make sacrifices during their own lifetime. Imagine if another generation tried to build the most comfortable life possible for their children, protecting them from ever having to make sacrifices for others. Those two generations, I think, would leave monumentally different marks on the world.

It’s such a paradox, I think. I don’t want to make noise about the sacrifices I’ve made, but I don’t want my sacrifices to be insulted by ungrateful children. I don’t want my children feel deep shame or know intense suffering, but I also want them to have opportunities to build inner strength. In some ways I need to tell stories about sacrifice, but in other ways that’s counterproductive. What’s a parent to do?

The only solution I can think of is to tell stories about the sacrifices of others. Instead of talking about my own sacrifices, I can tell my sons the sacrifices that their mother and grandparents made. I can let others tell my story, or let my sons ask me about my story and tell them the truth when they do. This is at least one way out of the paradox.

I hope, too, that elevating and honoring the sacrifices of others helps me to relieve myself of this searing resentment I have when our kids are so unintentionally insulting of the sacrifices we’ve made for them.

Getting Process Out of the Black Box

It seems to me that a simple, relatively cheap, way to radically change the performance of an organization is to take consequential processes that are implicit and make them simple, clear, and explicit.

The first three weeks after Emmett (our third son) was born, were unusually smooth. And then I went back to work.

Maybe I’m just a novice and I should’ve expected brother-brother conflict while our two older sons, Bo and Myles, jockeyed for new roles in the family. But when I went back to work, and perhaps coincidentally perhaps not, snap. The good times were over and their relationship flipped, seemingly overnight.

This rattled me. I don’t have a sibling and I was resentful toward my sons - that they didn’t realize how lucky they were. I made this known to them and performed several other magnificent feats of faux-parenting, including yelling, calling out mistakes, ignoring the bad behavior, ordering them to “work it out” - and probably several embarrassing and obviously ineffective strategies.

I was particularly frustrated with our older son, who was more frequently the instigator of conflict. Why doesn’t he get it? How is he not learning from this?, I thought.

After a particularly bad episode, involving a modest but intention punch to a defenseless brother’s chest, I accidentally had a small breakthrough. I AAR’d my son.

An AAR is an After-action review that I learned about when reading some books about the US Army’s approach to leadership. Basically, a unit should debrief right after a mission using four simple questions. These questions vary depending on where you read about it but they’re roughly this:

What did we intend?

What actually happened?

Why?

What should we do differently next time?

It turns out, even at 4 years old, Bo was pretty responsive to the AAR. He was capable of thinking through these questions with some modest support and he actually learned something. But the takeaway of this story is deeper than to “AAR your kids.” The real lesson is that important “processes” like helping my sons learn from a mistake shouldn’t be improvised; for the important stuff I shouldn’t be winging it.

—

Let’s simplify the world and say there are two kinds of organizational processes, explicit processes and implicit processes. I’m going to start with family stuff as an example, but as we’ll see shortly it applies to professional life as well.

Explicit processes are ones that are worked out, down to specific, simple steps. Explicit processes are the sorts of activities that everyone in our family has a mental checklist or process map for in their heads. In some instances, we even have simple diagrams drawn up on a whiteboard in our kitchen.

Here are some examples of explicit organizational processes in our family:

The routine at dinner / bedtime

The routine for how we get ready in the morning

The routine for how we get ready when we have to leave the house

The routine for drop-off and pick-up from school

The routine for cleaning up toys

The routine for feeding the dog

The meal plan for the week

To be sure, we don’t have perfect processes worked out for all these routines - we’re always learning and improving. But having any process that are explicitly understood to the entire family does two things: 1) we avoid rookie mistakes (and at least some toddler meltdowns), and, 2) we have a starting point for process improvement. For explicit processes, we’re decidedly not winging it. We have a plan that is explicitly known to everyone.

Implicit processes are the situations that we haven’t thought through in advance or taken the time to make specific, simple, or known to everyone. The way these processes work is in the metaphorical black box - they happen, but it’s not clear how or why - we’re essentially winging it on these. Some examples in our family, past and present, are:

How we coach our kids when they make mistakes

How we share information with our kids and family

How we learn and adjust as parents

How we resolve sibling conflict (and when we intervene as parents and when we don’t)

How we determine how much of a plate needs to be eaten before dessert is allowed.

Most of these are at least a little squishy in our household. But during the heart of Covid Robyn and I took something implicit - how we communicate a day-care Covid exposure and quarantine - and made it explicit. By working through the process and trying to make it simple, clear, and essentially into a checklist a few really good things happened:

We were calmer (because we had a plan to lean on)

We executed faster (because we knew our roles, and cut out unnecessary steps)

We executed better (because we didn’t panic and forget really important, but easy to miss steps like getting complete information from our day care provider about the exposure)

Making the implicit process explicit is a game changer, because routines that are made simpler and clearer go much better than when we wing it. And as I mentioned previously, explicit processes are much easier to improve iteratively.

Of course, in our professional lives not every implicit process is consequential enough to make implicit (e.g., it’s probably okay to wing it when picking a spot for the quarterly happy hour). But in my experience lots of really consequential processes in organizations are ones where most of us are essentially winging it. Or worse, the processes are explicit but are complex, bloated, or shoddily communicated…and as a result outcomes are actually worse than winging it.

Here are some examples - how many of these are explicit processes in your organization? How many are implicit?

How we learn from a failed project

How we manage in a crisis

How we hire, interview, fire, or promote fairly

How we react to changing consumer or market trends

How we coach and develop employees

How we support new managers or employees

How we make a big decision

How we plan or facilitate meetings

How we communicate major decisions or enterprise strategy

How we set goals and measure KPIs

How we scope out, form the right team, and launch a strategic initiative

How we make adjustments to the strategy or plan

How many of these should be simple, clear, and well understood? How many of these are okay to wing it?

It seems to me that a simple, relatively cheap way to radically change the performance of an organization - whether at work or at home - is to take consequential processes that are implicit and make them simple, clear, and explicit.

Bad Managers May Finally Get Exposed

If we’re lucky, the Great Resignation may only be the beginning.

Hot take: the shift to remote work will finally expose bad managers, and help good managers to thrive.

If I were running an enterprise right now, I’d be doubling down HARD on improving management systems and the capabilities of my organization’s leaders. Why?

Because bad management is about to get exposed.

This is merely a prediction, but even with all the buzz about the “Great Resignation” I actually think most organizations - even ones that are actively investing in “talent” - are underrating the impact of workforce trends that have started during the pandemic. The first order effect of these trends manifests in the Great Resignation (attrition, remote work, work-life balance) but I think the second-order effects will reverberate much more strongly in the long-run.

Here’s my case for why.

A fundamental assumption a company could make about most workers, prior to the pandemic, was that they were mostly locked in to living and working in the same metro or region as their office location. Now, hybrid and fully remote work is catching on, and this fundamental assumption of living and working in the same region is less true than it was three years ago.

This shift accelerates feedback loops around managers in two ways. One, it lowers the switching costs and broadens the job market for the most talented workers. Two, it opens up the labor pool for the most talented managers - who can run distributed teams and have the reputation to attract good people.

I think this creates a double flywheel, which creates second order effects on the quality of management. If this model holds true in real life, good managers will thrive and create spillover effects which raise the quality of management and performance in other parts of their firms. Bad managers, on the contrary, will fall into a doom loop and go the way of the dinosaur. Taken together, I hope this would raise the overall quality of managers across all firms.

Here’s a simple model of the idea:

Of course, these flywheels most directly affect the highest performing workers in fields which are easily digitized. But these shifts could also affect workers across the entire economy. For example, imagine a worker in rural America or a lesser known country, whose earnings are far below their actual capability. Let’s say that person is thoughtful and hard working, but is bounded by the constraints of their local labor market.

Unlike before, where they would have to move or get into a well known college for upward mobility - which are both risky and expensive - they can now more easily get some sort of technical certification online and then find a remote job anywhere in the world. That was always the case before, but the difference now is that their pool of available opportunities is expanded because more firms are hiring workers into remote roles - there’s a pull that didn’t exist before.

Here’s what I think this all means. If this prediction holds true, I think these folks would be the “winners”:

High-talent workers (obviously): because they can seek higher wages and greater opportunities with less friction.

High-talent managers: because they are better positioned to build and grow a team; high-talent workers will stick with good managers and avoid bad ones.

Nimble, well-run, companies: companies that are agile, flexible, dynamic, flat, (insert any related buzzword here) will be able to shape teams and roles to the personnel they have rather than suffocating potential by forcing talented people into pre-defined roles that don’t really fit them. A company that can adjust to fully utilize exceptional hires will beat out their competitors

Large, global, companies: because they have networks in more places, and are perhaps more able to find / attract workers in disparate places.

Talent identification and development platforms: if they’re really good platforms, they can become huge assets for companies who can’t filter the bad managers and workers from the good. Examples could be really good headhunters or programs like Akimbo and OnDeck.

All workers: if there are fewer bad managers, fewer of us have to deal with them!

And these are the folks I would expect to be the “losers”:

Bad managers: because they’re not only losing the best workers, they’re now subject to the competitive pressure of better managers who will steal their promotions.

Companies with expensive campuses: because they’re less able to woo workers based on facilities and are saddled with a sunk cost. Companies feeling like they have to justify past spend will adjust more slowly - ego gets in the way of good decisions, after all.