Is abundance enough? How much is enough?

I was thinking of a high school play - which satires Deux ex Machina - when thinking about the role of abundance and whether goodness is even necessary.

Friends,

I’m really excited for both podcast episodes this week. I hope you enjoy them.

In the first, I was remembering a play I was part of in high school. Woody Allen’s God. One of the satirical elements of the play is the Greek chorus in the play calling for Deus ex machina - “God in the machine” - by name to save everyone.

Will the abundance that innovation creates save us all? That’s a question I asked myself directly when writing Character by Choice.

Do we need to care about goodness and character? Would we be okay if we had a world full of abundance? Perhaps obviously, I didn’t think abundance was enough because I kept writing the book.

Link to S2E4 | Abundance.

I’m equally excited about this week’s audio reflection. Years ago, one of my best friends - Jeff - and I were talking about money. He had heard a book or podcast about money in the Bible and shared a question he was gnawing on. How much is enough? Not even theoretically, but what would the actually dollar amount be?

It’s a question that’s stayed with me for years and the main subject of this week’s guided audio reflection.

Link to S2E4.1 | How much is enough?

I hope you have a good week. If you’re in the US - don’t forget to make a plan to vote or complete your absentee ballot.

With love from Detroit,

Neil

Stale Incumbents Perpetuate Distrust

Low trust levels in America benefit groups like “stale incumbents,” who maintain their positions by fostering distrust and resisting change.

In a society where trust levels are low and have been falling for decades, have you ever wondered who stands to gain from this pervasive and persistent distrust?

My hypothesis is this: low trust isn’t just a social ill—it’s a profitable venture for some. Over the years, I’ve noticed different groups that seem to benefit from distrust, both within organizations and across our culture. In this post, I’ll share my observations and explore who profits from distrust. If you have your own observations or data, please share them as we delve into this critical issue together.

Adversaries

The first group that benefits from low trust is straightforward: our adversaries. Distrust and infighting often go hand in hand. It’s much easier to defeat a rival, whether in the market, in an election, in a war, or in a race for positioning, when they are busy fighting among themselves and imploding from within.

Brokers

Another group that profits from distrust are brokers. Though they often don’t have bad intentions, brokers make a living by filling the gap that distrust creates. By “broker,” I mean someone who advocates on our behalf in an untrusting or uncertain environment. This could be a real estate agent, someone who vouches for us as a business partner, a friend who sets people up on blind dates, or someone whose endorsement wins us favor with others.

Mercenaries

Mercenaries are a less well-intentioned version of brokers. These people paint a dark picture of a distrustful world and then offer to fight for us or provide protection—for a price. Mercenaries never portray themselves as such, even if that’s what they really are.

Aggregators

Aggregators are people or organizations that build a reputation for being consistently trustworthy, especially when their rivals are not. Essentially, they aggregate trust and communicate it as a symbol of value. A good example of aggregators are fast food brands. When traveling abroad, people trust an American fast food chain to be clean, consistent, and reasonably priced. Many brands across industries thrive because they’ve built a trustworthy reputation.

These groups are fairly straightforward, and many of you might find these categories intuitive and relatable. However, they didn’t seem to cover enough ground to explain the persistent low trust levels in our culture. As I thought more about it, I realized that the largest group benefiting from distrust might be hidden in plain sight…

Stale Incumbents

Now, let’s consider the largest group that might be benefiting from distrust: stale incumbents.

Imagine someone you’ve worked with who always slows down projects. They resist learning new things and believe in sticking to the old ways. They’re nice, but their team never meets deadlines or finishes projects—they always have a believable excuse. This person is a stale incumbent.

More specifically, a stale incumbent is someone in a position who is out of ideas or motivation to innovate. Their ability to keep their job depends on everyone being stuck in the status quo. Here’s how it works:

They get into a comfortable position.

They stop learning and trying new things.

They run out of ideas because they stopped learning.

They try to hide and let new ideas fade.

They allow distrust and low standards to settle in.

When new people ask questions, they blame distrust: “It’s not my fault; others aren’t cooperating.”

They make the status quo seem inevitable, doing the minimum to keep their position and discourage change.

They repeat steps 4-7.

Stale incumbents need distrust to hide behind. They want to keep their comfortable position but have no new ideas because they stopped learning. A culture of distrust is the perfect scapegoat: it can’t argue back, and people think it can’t be changed, so they stop asking questions and give up. The distrust also makes it harder for new people to show up, innovate, annd expose the stale incumbent.

Ultimately, stale incumbents can keep their jobs while delivering mediocre results. This staleness spreads, making the culture of distrust harder to reverse because more stale incumbents depend on it. It’s a cycle of mediocrity, not anger and fear.

I don’t have experimental data, but I do have decades of regular observation draw from. I believe stale incumbents help explain the persistent low trust in America. Many people started with energy but never found allies, and the stale culture assimilated them.

The good news is there’s hope. If distrust is due to stale incumbents rather than malicious actors, we may not face much resistance in bringing about change. The path to change is clear: bring in energetic people and help them bring others along. It’s hard, but not complicated. By fostering a culture of learning, innovation, and trust, we can break the cycle of mediocrity and create a more trusting and dynamic society.

Doing Strategy in Politics

Don’t give me a platform without a vision first!

Here’s my thought experiment for how we might do political visioning in America, grounded in the aspirations of the entire polity.

The first bit is a good illustration of how I think about the American Dream. But for what it’s worth, I mean this post more as an exercise in how to “do” politics differently than just having a platform on 50+ issues that matter to the polity and shouting about it as loud as you can - not an unpacking of my own vision.

My main consternation as a citizen is this: I don’t want a policy platform unless you’ve shared a bona fide vision first! Rather than just griping, I figured I’d actually explain how I think things could work instead.

And, for what it’s worth, this is how I’ve seen great organizations function across sectors. This sort of discipline around strategy and execution is one of the things I most wish the public sector would adopt from private sector organizations and business school professors.

To start, let’s assume a visionary political leader believes these are the three overarching questions that unify the largest possible amount of our polity:

On average, do people have enough optimism about the present and future to want to bring children into this world?

On average, once someone is brought into this world, do they flourish from cradle to grave?

Overall, the simplest and most comprehensive way to measure the health of a society is Total Fertility Rate vs. replacement rate. Is our long-run population stable, growing, or declining?

Thinking about the fundamental need gripping the polity is key. I think whether or not people want to reproduce is a good bellwether of a LOT and therefore a good framework for contemplating political issues at a national level.

A vision statement based on these questions could be:

I imagine a country where our citizens believe it’s worth bringing children into the world and have reasonable confidence that those children will flourish during their lifetimes.

A vision statement statement has to describe the world after you’ve succeeded from the POV of the citizen, not the work itself.

A pithy slogan / mission (which does sharply focus and describe the work itself) to capture the essence of this vision statement could be:

“Families will thrive here.”

Let’s assume this is a vision / mission statement that the polity believes in. If so, then the political leader can translate their rhetoric into action by asking two simple questions:

Is the vision true today?

If not, what would have to be true for the vision to become reality?

From there, a political leader can create an integrated set of mutually reinforcing policy and administrative choices that they believe will allow the polity to make disproportionate progress toward the vision state.

Put another way, by working backwards from the vision, you can place bets on the initiatives that are more likely to succeed rather than wasting resources on those that won’t get us to where we agreed we want to go.

The problem with this approach is that you actually have to articulate a vision, understand the root causes that are preventing it from happening without intervention, do the extremely abstract work of forming a strategy, and then communicate it clearly enough so that people get behind it. That’s really hard, and you have to have major guts to go through this exercise of vision -> strategy -> priorities -> outcomes.

This is quite different, I think, than simply articulating a pro-con list of policy preferences across a widely distributed set of issue areas that aren’t contemplated in an integrated way. But the thing is, having focus and priorities tends to work much better than “boiling the ocean” or “being all things to all people.”

To be fair, I’ve seen some contemporary politicians operate this way. Not many though.

In a nutshell, one of the biggest lessons I’ve learned from observing the leadership of private-sector companies is that it’s a big waste to just start doing stuff in a way that’s not integrated and focused—as if every possible initiative is equally impactful. It works much better when you start with a specific end state in mind and work backwards. It’s an idea that’s useful for political leaders, too.

My Dream: Bringing CX to State and Local Government

Bringing CX to State and Local Government would be a game-changer for everyday people.

My number one mission for my professional life is to help government organizations become high performing. If every government were high performing, I think it would change the trajectory of human history for the better in a big way.

One way to do that is to bring customer experience (CX) principles pioneered in the private sector and some forward thinking places (like the US Federal Government, the UK Government, or the Government of Estonia) and bring them to State and Local Government.

It is my dream to create CX capabilities in City and State Government in Michigan and have our state be a model for how CX can work at the State and Local level across the country.

Dreams don’t come true unless you talk about them. So I’m talking about it.

If you have the same mission or the same dream, I want to meet you. If you have friends or colleagues who have similar missions or dream, I want to meet them too. We who care about high performing, citizen-centric government want to make this happen. I want to play the role that I can play to bring CX to State and Local Government and I want to help you on your journey. Full stop.

I have so much more to say about what this could be, but I had to start somewhere. I had ChatGPT help me take some thoughts in my head and convert them into a Team Charter and a Job Description for the head of that team.

What do you think? Have you seen this? What would work? What’s missing? Maybe we can make something happen together, which is exactly why I’m putting a tiny morsel of this idea out there for those who care to react to.

The country and world are already moving to more responsive, networked, citizen-centric models of how government can work. Let’s hasten that transformation by bringing CX principles to the work our City and State Governments do every day.

I can’t wait to hear from you.

-Neil

—

Team Charter for Customer Experience (CX) Improvement in City or State Government

Purpose (Why?)

To transform and enhance the quality of government services and citizens’ daily life through CX methodologies. High impact domains include touchpoints with significant impact for the citizens who are engaged (e.g., support for impoverished families obtaining benefits) and those touchpoints affecting all citizens (e.g., tax payments, vehicular transportation), and touchpoints with high community interest.

Objectives (What Result Are We Trying to Create?)

Increase citizen satisfaction

Strengthen trust in government

Elevate the quality of life for residents, visitors, and businesses

Scope (What?)

This initiative will focus on the top 5-7 stakeholders personas driving the most value to start:

Improve how citizens experience government services, daily life, and vital community aspects

Drive change cross-functionally and at scale across interaction channels

Foster tangible improvements in the quality of life

Create and align KPIs with community priorities and establish ways to measure and communicate success

Activities (How?)

Segment residents, visitors, businesses, and identify top personas and touchpoints

Develop customer personas, journey maps, and choose highest-value problem areas to focus on for each persona

Prioritize and create an improvement roadmap

Partner with various stakeholders to drive change

Measure results, gather feedback, and align with community priorities

Share progress regularly and communicate value to stakeholders to gain momentum and support

Team and Key Stakeholders (Who?)

Leadership: A head with experience in leadership, CX methods, data, technology, innovation, and intrapreneurship

Department Liaisons: Individuals driving CX within different governmental departments

External Partners: Collaboration with other government agencies, citizen groups, foundations, the business community, and vendors

Core Team: A mix of professionals with expertise in relationship management, digital, innovation, leadership, and related fields

Timeline and Next Steps (When?)

0-6 Months: Segmentation, personas, and journey mapping

6-12 Months: Problem analysis and a prioritized roadmap creation

9-18 Months: Tangible improvements and iterative changes in focus areas

Ongoing: Continual refinement and adaptation to changing needs and priorities

—

Job Description: CX Improvement Team Leader

Position Overview:

As the CX Improvement Team Leader for City or State Government, you will drive transformative change to enhance citizens’ experience with government services and improve quality of life for citizens in this community. You will guide a cross-functional team to create innovative solutions, aligning with community priorities and creating tangible improvements in quality of life.

Responsibilities:

Lead and inspire a diverse team to achieve objectives

Create and align KPIs, establish methods for measurement

Develop and execute an improvement roadmap

Engage with stakeholders across government agencies, citizen groups, businesses, and more

Regularly share progress and communicate the value of initiatives to gain momentum and support

Collaborate with external partners and vendors as needed

Foster an innovative and responsive culture within the team

Qualifications:

Minimum of 10 years of experience in customer experience, leadership, technology, innovation, or related fields

Proven ability to drive change at scale across various channels

Strong communication and relationship management skills

Experience in government, public policy, or community engagement is preferred

A visionary leader with a passion for improving lives and a commitment to public service

Photo by NordWood Themes on Unsplash

Maximizing Organizational Performance: 7 Key Questions

Making organizations better is hard, but it doesn’t have to be complicated.

Leaders are often charged with "making the organization perform better." That's an incredibly difficult mission unless we understand what an organization, especially ours, is and how it works. Only then can we diagnose organizational problems and make improvements.

This is a pretty long, nerdy post, so here's the tl;dr for those in a hurry, and for those who need a little taste to prove the read is worth it.

If you're trying to make an organization perform better, start by asking (just) seven questions. I think you'll make sense of your biggest problems pretty quickly:

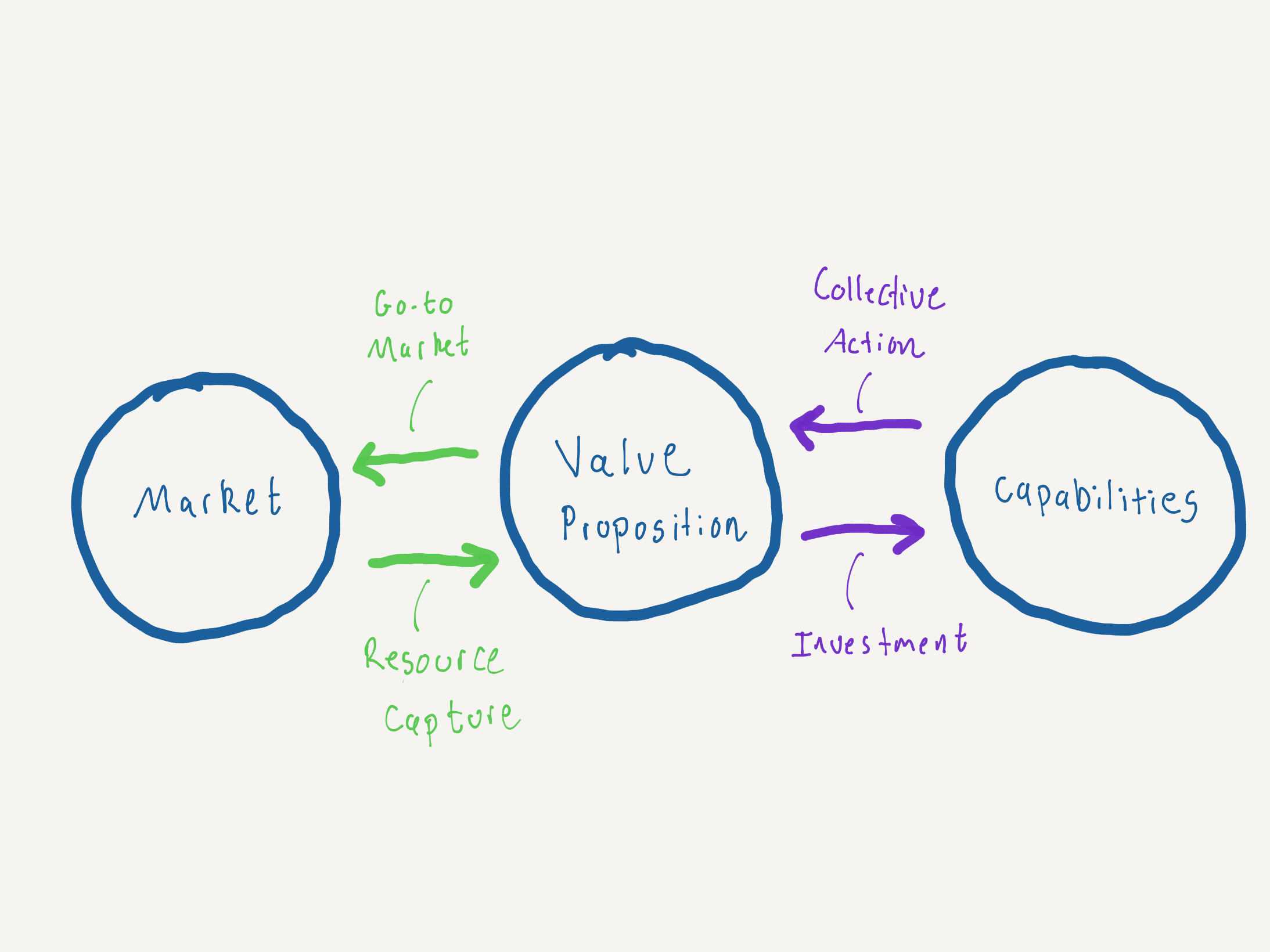

Value Proposition: What do we create that other people are willing to sacrifice something (i.e., pay) for?

Market: Who cares about what we have to offer?

Capabilities: What are the handful of things we really need to be good at to create something of value?

Go-to-Market Systems: How will we engage with our market?

Resource Capture Systems: How does the organization get the resources it needs?

Collective Action Systems: How will we work together to turn our capabilities into something of value?

Investment Systems: How will we develop the capabilities that matter most?

Making organizations better is hard, but it doesn't have to be complicated.

Leaders are often charged to “make the organization perform better”. That’s an incredibly difficult mission unless we understand what an organizations, especially ours, is and how it works. Only then can we diagnose organizational problems and make improvements.

This is a pretty long, nerdy, post so here’s the tl;dr for those in a hurry, and for those that need a little taste to prove the read is worth it.

If you’re trying to make understand and organization and help it perform better, start with asking (just) seven questions. I think you’ll make sense of your biggest problems pretty quickly:

Value Proposition: What do we create that other people are willing to sacrifice something (i.e., pay) for?

Market: Who cares about what we have to offer?

Capabilities: What are the handful of things we really need to be good at to create something of value?

Go-to-Market Systems: How will we engage with our market?

Resource Capture Systems: How does the organization get the resources it needs?

Collective Action Systems: How will we work together to turn our capabilities into something of value?

Investment Systems: How will fwe develop the capabilities that matter most?

Making organizations better is hard, but it doesn’t have to be complicated.

The Seven-Part Model of Organizations

So, what is an organization?

I'd propose that an organization, at its simplest, is only made up of seven components:

Value Proposition

Market

Capabilities

Go-to-Market Systems

Resource Capture Systems

Collective Action Systems

Investment Systems

If we can understand these seven things about an organization, we can understand how it works and consequently make it perform better. There are certainly other models and frameworks for understanding organizations (e.g., McKinsey 7-S, Business Model Canvas, Afuah Business Model Innovation Framework) which serve specific purposes - and I do like those.

This seven-part model of organizations is the best I've been able to produce which maintains simplicity while still having broad explanatory power for any organization, not just businesses. Each component of the model answers an important question that an organization leader should understand.

The seven parts (Detail)

The first three parts of the model are what I think of as the outputs - they're the core foundation of what an organization is: a Value Proposition, a Market, and a set of Capabilities.

Value Proposition: What do we create that other people are willing to sacrifice something (i.e., pay) for?

The Value Proposition is the core of an organization. What do they produce or achieve? What is the good or the service? What makes them unique and different relative to other alternatives? This is the bedrock from which everything else can be understood. Why? Because the Value Prop is where the internal and external view of the organization come together - it's where the rubber meets the road.

It's worth noting that every stakeholder of the organization has to be satisfied by the Value Proposition if they are to engage with the organization: customers, constituents, shareholders, funders, donors, employees, suppliers, communities, etc.

Market: Who cares about what we have to offer?

Understanding the Market is also core to an organization because any organization needs to find product-market fit to survive. This question really has two subcomponents to understand: who the people are and what job they need to be done or need that they have that they're willing to sacrifice for.

It's not just businesses that need to clearly understand their Markets - governments, non-profits, and even families need to understand their Market. Why? Because no organization has unlimited resources, and if the Value Proposition doesn't match the Market the organization is trying to serve, the organization won't be able to convince the Market to part with resources that the organization needs to survive - whether that's sales, time, donations, tax revenues, or in the case of a family, love and attention from family members.

Capabilities: What are the handful of things we really need to be good at to create something of value?

Thus far, we've talked about what business nerd types call "product-market fit," which really takes the view that the way to understand an organization is to look at how it relates to its external environment.

But there's also another school of thought that believes a firm is best understood from the inside out - which is where Capabilities come in.

Capabilities are the stuff that the organization has or is able to do which they need to be able to produce their Value Proposition. These could be things like intellectual property or knowledge, skills, brand equity, technologies, or information.

Of course, not all Capabilities are created equal. When I talk about Capabilities, I'm probably closer to what the legendary CK Prahalad describes as "core competence." Let's assume our organization is a shoe manufacturer. Some of the most important Capabilities probably are things like designing shoes, recruiting brand ambassadors, and manufacturing and shipping cheaply.

The shoe company probably also has to do things like buy pens and pencils - so sure, buying office supplies is a Capability of the firm, but it's not a core Capability to its Value Proposition of producing shoes. When I say "Capabilities," I'm talking about the "core" stuff that's essential for delivering the Value Proposition.

Finally, we can think of how Capabilities interact with the Value Proposition as an analog to product-market fit, let's call it "product-capability fit." Aligning the organization with its external environment is just as important as aligning it to its internal environment.

When all three core outputs - Value Proposition, Market, and Capabilities - are in sync, that's when an organization can really perform and do something quite special.

In addition to the three core outputs, Organizations also have systems to actually do things. These are the last four components of the model. I think of it like the four things that make up an organization's "operating system."

Go-to-Market Systems: How will we engage with our Market?

How an organization "goes to market" is a core part of how an organization operates. Because after all, if the product or service never meets the Market, no value can ever be exchanged. The Market never gets the value it needs, and the organization never gets the resources it needs. A good framework for this is the classic marketing framework called the 4Ps: Price, Product, Place, and Promotion.

But this part of the organization's "operating system" need not be derived from private sector practice. Governments, nonprofits, faith-based organizations, and others all have a system for engaging with their Market; they might just call it something like "service delivery model," "logic model," "engagement model," or something else similar.

The key to remember here is that go-to-market systems are not how parties within the organization work together; it's how the organization engages with its Market.

Resource Capture Systems: How will the organization get the resources it needs?

Just like a plant or an animal, organizations need resources to survive. But instead of things like food, sunlight, water, and oxygen, and carbon dioxide, organizations need things like money, materials, talent, user feedback, information, attention, and more.

So if you're an organizational leader, it's critical to understand what resources the organization needs most, and having a solid plan to get them. Maybe it's a sales process or levying of a tax. Maybe it's donations and fundraising. Maybe for resources like talent, it's employer branding or a culture that makes people want to work for the organization.

This list of examples isn't meant to be comprehensive, of course. The point is that organizations need lots of resources (not just money) and should have a solid plan for securing the most important resources they need.

Collective Action Systems: How will we work together to turn our capabilities into something of value?

Teamwork makes the dream work, right? I'd argue that's even an understatement. The third aspect of the organization's operating system is collective action.

This includes things like operations, organization structure, objective setting, project management approaches, and other common topics that fall into the realm of management, leadership, and "culture."

But I think it's more comprehensive than this - concepts like mission, purpose, and values, decision chartering, strategic communications, to name a few, are of growing importance and fall into the broad realm of collective action, too.

Why? Two reasons: 1) organizations need to move faster and therefore need people to make decisions without asking permission from their manager, and, 2) organizations increasingly have to work with an entire network of partners across many different platforms to produce their Value Proposition. These less-common aspects of an organization's collective action systems help especially with these challenges born of agility.

So all in all, it's essential to understand how an organization takes all its Capabilities and works as a collective to deliver its Value Proposition - and it's much deeper than just what's on an org chart or process map.

Investment Systems: How do we develop the capabilities that matter most?

It's obvious to say this, but the world changes. The Market changes. Expectations of talent change. Lots of things change, all the time. And as a result, our organizations need to adapt themselves to survive - again, just like Darwin's finches.

But what does that really mean? What it means more specifically is that over time the Capabilities an organization needs to deliver its Value Proposition to its Market changes over time. And as we all know, enhanced Capabilities don't grow on trees - it takes work and investment, of time, effort, money, and more.

That's where the final aspect of an organization's operating system comes in - the organization needs systems to figure out what Capabilities they need and then develop them. In a business, this could mean things like "capital allocation," "leadership development," "operations improvement," or "technology deployment."

But the need for Investment Systems applies broadly across the organizational world, too, not just companies.

As parents, for example, my wife and I realized that we needed to invest in our Capabilities to help our son, who was having a hard time with feelings and emotional control. We had never needed this "capability" before - our "market" had changed, and our Value Proposition as parents wasn't cutting it anymore.

So we read a ton of material from Dr. Becky and started working with a child and family-focused therapist. We put in the time and money to enhance our "capabilities" as a family organization - and it worked.

Again, because the world changes, all organizations need systems to invest in themselves to improve their capabilities.

My Pitch for Why This Matters

At the end of the day, most of us don't need or even want fancy frameworks. We want and need something that works.

I wanted to share this framework because this is what I'm starting to use as a practitioner - and it's helped me make sense of lots of organizations I've been involved with, from the company I work for to my family.

If you're someone - in any type of organization, large or small - I hope you find this very simple set of seven questions to help your organization perform better.

Making organizations better is hard, but it doesn't have to be complicated.

The potential of Government CX to improve social trust

Government CX is a huge opportunity that we should pursue.

Several times last week, while traveling in India, people cut in front of my family in line. And not slyly or apologetically, but gratuitously and completely obliviously, as if no norms around queuing even exist.

In this way, India reminds me of New York City. There are oodles and oodles of people, that seem to all behave aggressively - trying to get their needs met, elbowing and jockey their way through if they need to. It’s exhausting and it frays my Midwestern nerves, but I must admit that it’s rational: it’s a dog eat dog world out there, so eat or be eaten.

What I realized this trip, is that even after a few days I found myself meshing into the culture. Contrary to other trips to India, I now have children to protect. After just days, I began to armor up, ready to elbow and jockey if needed. I felt like a different person, more like a “papa bear” than merely a “papa”. like a local perhaps.

I even growled a papa bear growl - very much unlike my normal disposition. Bo, our oldest, had to go to the bathroom on our flight home so I took him. We waited in line, patiently, for the two folks ahead of us to complete their business. Then as soon as we were up, a man who joined the line a few minutes after us just moved toward the bathroom as if we had never been there waiting ahead of him

Then the papa bear in me kicked in. This is what transpired in Hindi, translated below. My tone was definitely not warm and friendly:

Me: Sir, we were here first weren’t we?

Man: I have to go to the bathroom.

Me: [I gesture toward my son and give an exasperated look]. So does he.

And then I just shuffled Bo and I into the bathroom. Elbow dropped.

But this protective instinct came at a cost. Usually, in public, I’m observant of others, ready to smile, show courteousness, and navigate through space kindly and warmly. But all the energy and attention I spent armoring up, after just days in India, left me no mind-space to think about others.

This chap who tried to cut us in line, maybe he had a stomach problem. Maybe he had been waiting to venture to the lavatory until an elderly lady sitting next to him awoke from a nap. I have no idea, because I didn’t ask or even consider the fact that this man may have had good intentions - I just assumed he was trying to selfishly cut in line.

Reflecting on this throughout the rest of the 15 hour plane ride, it clicked that this toy example of social trust that took place in the queue of an airplane bathroom reflects a broader pattern of behavior. Social distrust can have a vicious cycle:

Someone acts aggressively toward me

I feel distrust in strangers and start to armor up so that I don’t get screwed and steamrolled in public interactions

I spend less time thinking about, listening to, and observing the needs of others around me

I act even more aggressively towards strangers in public interactions, because I’m thinking less about others

And now, I’ve ratcheted up the distrust, ever so slightly, but tangibly.

The natural response to this ratcheting of social distrust is to create more rules, regulations, and centralize power in institutions. The idea being, of course, that institutions can mediate day to day interactions between people so the ratcheting of social distrust has some guardrails put upon it. When social norms can’t regulate behavior, authority steps in.

The problem with institutional power, of course, is that it’s corruptible and undermines human agency and freedom. Ratcheting up institutional power has tradeoffs of its own.

—

Later during our journey home, we were waiting in another line. This time we were in a queue for processing at US Customs and Border patrol. This time, I witnessed something completely different.

A couple was coming through the line and they asked us:

Couple: Our connecting flight is boarding right now. I’m so sorry to ask this, but is it okay if we go ahead of you in line?

Us: Of course, we have much more time before our connecting flight boards. Go ahead.

Couple: [Proceeds ahead, and makes the same request to the party ahead of us].

Party ahead of us: Sorry, we’re in the same boat - our flight is boarding now. So we can’t let you cut ahead.

Couple: Okay, we totally understand.

The first interaction in line at the airplane bathroom made me feel like everyone out there was unreasonable and selfish. It undermined the trust I had in strangers.

This interaction in the customs line had the opposite effect, it left me hopeful and more trusting in strangers because everyone involved behaved considerately and reasonably.

First, the couple acknowledged the existence of a social norm and were sincerely sorry for asking us to cut the line. We were happy to break the norm since we were unaffected by a delay of an extra three minutes. And finally, when the couple ahead said no, they abided by the norm.

We were all observing, listening, and trying to help each other the best we could. In my head, I was relieved and I thought, “thank goodness not everyone’s an a**hole.

It seems to me that just as there’s a cycle that perpetuates distrust, there is also a cycle which perpetuates trust:

Listen and seek to understand others around you

Do something kind that helps them out without being self-destructive of your own needs

The person you were kind toward feels higher trust in strangers because of your kindness

The person you were kind to can now armor down ever so slightly and can listen for and observe the needs of others

And now, instead of a ratchet of distrust, we have a ratchet of more trust. Instead of being exhausting like distrust, this increase in trust is relieving and energy creating.

—

At the end of the day, I want to live in a free and trusting society. If there was to be one metric that I’m trying to bend the trajectory on in my vocational life - it’s trust. I want to live in a world that’s more trusting.

This desire to increase trust in society is why I care so much about applying customer experience practices to Government. Government can disrupt the cycle of distrust and start the flywheel of trust in a big way - and not just between citizens and government but across broader culture and society.

Imagine this: a government agency, say the National Parks Service, listens to its constituents and redesigns its digital experience. Now more and more people feel excited about visiting a National Park and are more able to easily book reservations and be prepared for a great trip into one of our nation’s natural treasures.

So now, park visitors have more trust in the National Park Service going into their trip and are more receptive to safety alerts and preservation requests from Park Rangers. This leads to a better trip for the visitor, a better ability for Rangers to maintain the park, and a higher likelihood of referral by visitors who have a great trip. This generates new visitors and adds momentum to the flywheel.

I’m a dataset of one, but this is exactly what happened for me and my family when we’ve interacted with the National Parks’ Service new digital experience. And there’s even some data from Bill Eggers and Deloitte that is consistent with this anecdote: CX is a strong predictor of citizens’ trust in government.

And now imagine if this sort of flywheel of trust took place across every single interaction we had with local, state, and federal government. Imagine the mental load, tension, and exhaustion that would be averted and the positive affect that might replace it.

It could be truly transformational, not just with what we believe about government, but what we believe about the trustworthiness of other citizens we interact with in public settings. If we believe our democratic government - by the people and for the people - is trustworthy, that will likely help us believe that “the people” themselves are also more trustworthy. After all, Government does shape more of our. daily interactions than probably any other institution, but Government also has an outsized role in mediating our interactions with others.

Government CX is a huge opportunity that we should pursue, not only because of the improvement to delivery of government service or the improvement of trust in government. Improvement to government CX at the local, state, and federal levels could also have spillover effects which increase social trust overall. No institution has the reach and intimate relationship with people to start the flywheel of trust like customer-centric government could, at least that I can see.

Photo by George Stackpole on Unsplash

Light only spreads exponentially

The algorithm is simple: Light, spread, teach others to spread.

We start with nothing.

And that in a way gives us a beginning. Nothing is from where we all start.

What we need first then, to spread light, is a candle. We need substance. We need our bodies. We need education. We need love. We need food, a home, and a place to work. We need all these things, which are a vessel to sustain light. For some, this candle is a birthright or a gift. Some of us must make our own.

Next, we light the candle. We figure out something which illuminates. We do something which illuminates. Maybe, too, our candle is lit by others and we are illuminated with a light that has been passed on to us. We somehow find a way to bring light into the world and there we are, with candle lit.

But this is not how light spreads. One candle, alone, does not illuminate a whole world of dark places, or even a whole city, or neighborhood, or even one room necessarily. To light up the world we must spread our light.

So we light our candle or let ourselves be lit, then we light two others. That makes three. But this is not enough, either, because three lit candles that will all wax and wane for a moment and then extinguish at the end of a life is surely not enough to illuminate a room, a neighborhood, or a world.

So what then?

The algorithm to spread light is simple, I think. It’s a compounding algorithm. We light our candle, then we light two others. But then, those two must light two others. And then those four light two others each. This is how light spreads, two by two by two. Light only spreads exponentially.

So what this means is that as parents, to really spread the light we cannot stop at being good parents, or teaching our kids how to be parents - we teach our kids to be teachers of parenting and be teachers of parenting ourselves. We cannot stop at being good people managers, or by mentoring the next generation of leaders, we must teach our mentees to make more mentors.

We can’t just make the light. We can’t just spread the light. We must teach others how to spread light. This is the algorithm for spreading light: light, spread, and teach how to spread.

—

We end with nothing.

What remains of us is what we leave behind. So a key question becomes, what should we try to leave behind?

First, I think we should leave behind something good. Something positive that benefits others and leaves the world better for us being there. Human life is a special thing, even after accounting for all the suffering it possesses. Why not leave something behind which honors this human life, this earth, and brings light to dark places?

It seems to me, that if we leave behind something positive and good we ought to leave something that endures, too. Leaving behind something enduring, that illuminates and gives light for a longer time, is better than something that fades quickly.

I don’t know if nothing lasts forever, or maybe some things last forever after all. But given the choice, why not strive for something closer to forever? But what endures, then? What lasts closer to forever?

Even if I were the wealthiest man alive, and passed down the largest inheritance - it would maybe last a few generations. All my photographs, too, will eventually become irrelevant. Our home will eventually change hands, and will be rebuilt or razed. My blog posts, hardly relevant to begin with will be forgotten. Anything that can be consumed, it seems, will eventually fade.

The chance we have then is to leave behind something that can regenerate itself?.

Kindness, for example, regenerates itself. Because when we are kind, it makes others kinder, and that in turn makes even more others kinder. Kindness regenerates. Knowledge is similar. When we create and share knowledge, it inspires the creation of new knowledge, leaving behind a larger body of knowledge from which to create. Knowledge also regenerates.

Good institutions are designed to regenerate. Think of the world’s leading companies and the most enduring governments.

The ones that last are built upon a premise of looking outward, seeing the new needs and having a genuine concern for a noble purpose. Those institutions then take the challenges of a changing world, channel them inward, and then regenerate themselves into something new. The moment that the most established of the world’s most high-profile institutions - like the world’s religions traditions, liberalism, Apple Computer, the US Constitution, or even Taylor Swift - stop regenerating themselves, they’ll begin to fade away like all the rest.

—

So the absolute, most essential question I could answer related to spreading the light is - what can I leave behind that’s positive and might actually last? If when I leave this world, I am only what I leave behind - what can I leave behind that regenerates and endures?

I don’t believe that careers and promotions are regenerative. The enduring impact of my position or title will start fading when I retire and end completely when I die. Nobody will care about my LinkedIn profile after I’m out of the game.

But what will last is a coaching tree of ethical and effective managers if I’m able to create one. What will last is the knowledge of unmet customer needs, if I’m able to bake that understanding into the DNA of companies and institutions. If I can build teams that don’t depend on fear, control, and hierarchy - and those teams actually succeed - they’ll regenerate and create more teams of their own. Those things regenerate, not my career in and of itself.

Simply having a happy marriage and happy children won’t regenerate either. What might last is if we can make such an impression on those around us and share all our secrets for a happy life, so that it starts a chain reaction which regenerates the families and marriages of others, that might endureHaving a wonderful marriage and happy children would be terrific, but those two achievements on their own won’t endure. What will endure is figuring out the secret sauce and then open sourcing the recipe.

When I talk to older people - whether friends or family - their concerns are different than mine. They seem less concerned with what they have and more concerned with what they can give back. As their time winds down, so does their ego. They start to look beyond their own lives.

What’s gut wrenching is when those people can’t prove to themselves that they’ve spread light. Or when they believe they haven’t prepared those that follow to spread light. Or worst of all, when they believe they’ve run out of time. Because spreading light and preparing others to spread light takes time. To see that realization is to witness agony.

—

What the hell have I been doing? For these past three decades, what have I been solving for? Have I been solving for building the world’s biggest candle? Have I been solving for lighting my own candle? Or have I been solving for spreading the light?

If I was solving for spreading the light, I think I would be acting so much differently than I am now.

I wouldn’t care as much about a career trajectory or a “dream job”, I’d just be walking the path of greatest different and would be spending much more time building up others to succeed and teach others.

I too, would be thinking about how to help others outside the four walls of our home, or at least really being generous with time and energy for the people who live near us or who are closest to us. I wouldn’t be waiting for the perfect cause to support or the perfect kid to mentor. I’d just be going for it and creating more builders of others.

And, I certainly wouldn’t be spending as much time pouting about all the others who behave badly toward me or be putting up a facade of politeness. If I was really solving for spreading the light, every conversation I had would be open, honest, sincere, and showing genuine concern for others. It’d be all heart and no polish.

If I were solving for spreading the light, I think I would be acting much differently. God willing, I have time to be different.

Photo by Rebecca Peterson-Hall on Unsplash

Corporate Strategy, CX, and the end of gun violence

Techniques from the disciplines of corporate strategy and customer experience can help define the problem of gun violence clearly and hasten its end.

What gut punches me about gun violence, beyond the acts of violence themselves, is not that we’ve seemed to make little progress in ending it. What grates me is that we shouldn’t expect to make progress. We shouldn’t expect progress because in the United States, generally speaking, we haven’t actually done the work to define the problem of gun violence clearly enough to even attempt solving it with any measure of confidence.

Gun violence is an incredibly difficult problem to solve, it’s layered, it’s complex, and the factors that affect gun violence are intertwined in knots upon knots across the domains of poverty, justice, health, civil rights, land use, and many others.

Moreover, it’s hard to prevent gun violence because different types of violence are fundamentally different, requiring different strategies and tactics. What it takes to prevent gang violence, for example, is extremely different from what it takes to prevent mass shootings. Forgive my pun, but in gun violence prevention, there’s no silver bullet.

I know this because I lived it and tried to be a small part in ending gun violence in Detroit. I partnered with people across neighborhoods, community groups, law enforcement, academia, government, the Church, foundations, and the social sector on gun violence prevention - the best of the best nationwide - when I worked in City Government, embedded in the equivalent of a special projects unit within the Detroit Police Department.

Preventing gun violence is the hardest challenge I’ve ever worked on, by far.

Just as I’ve seen gun violence prevention up close - I’ve also worked in the business functions of corporate strategy and customer experience (CX) for nearly my entire career - as a consultant at a top tier firm, as a graduate student in management, as a strategy professional in a multi-billion dollar enterprise, and as a thinker that has been grappling with and publishing work on the intricacies of management and organizations for over 15 years.

(Forgive me for that arrogant display of my resume, the internet doesn’t listen to people without believing they are credentialed).

I know from my time in Strategy and CX that difficult problems aren’t solved without focus, the discipline to make the problem smaller, accepting trade-offs, and empathizing deeply with the people we are trying to serve and change the behavior of.

This is why how we approach gun violence in the United States, generally speaking, grates me. Very little of the public discourse on gun violence prevention - outside of very small pockets, usually at the municipal level - gives me faith that we’re committed to the hard work of focusing, making the problem smaller, accepting trade-offs and empathizing deeply with the people - shooters and victims - we are trying to change the behavior of.

If I had to guess, there are probably less than 100 people across the country who have lived gun violence prevention and business strategy up close, and I’m one of them. The solutions to gun violence will continue to be elusive, I’m sure - just “applying business” to it won’t solve the problem.

However, all problems, especially elusive ones like gun violence, are basically impossible to solve until they are defined clearly and the strategy to achieve the intended outcome is focused and clearly communicated. To understand and frame the problem of gun violence, approaches from strategy and CX are remarkably helpful.

This post is my pitch and the simplest playbook I can think of for applying field-tested practices from the disciplines of strategy and CX to gun violence prevention. My hope is that by applying these techniques, gun violence could become a set of solvable problems. Not easy, but solvable nonetheless.

If you can’t put it briefly and in writing the strategy isn’t good enough

The easiest, low-tech, test of a strategy, is whether it can be communicated in narrative form, in one or two pages. If someone trying to lead change can do this effectively, it probably means the strategy and how it’s articulated is sound. If not, that change leader should not expect to achieve the result they intend.

The statement that follows below is entirely made up, but it’s an illustration of what clear strategic intent can look like. I’ve written it for the imaginary community of “Patriotsville”, but the framework I’ve used to write it could be applied by any organization, for any transformation - not just an end to gun violence. Further below I’ll unpack the statement section by section to explain the underlying concepts borrowed from business strategy and CX and some ideas on how to apply them.

Instead of platitudes like, “we need change” or “enough is enough” or “the time is now”, imagine if a change leader trying to end gun violence made a public statement closer to the one below. Would you have more or less confidence in your community’s ability to end gun violence than you do now?

Two-Pager of Strategic Intent to End Gun Violence in Patriotsville

We have a problem in Patriotsville, too many young people are dying from gunshot wounds. We know from looking at the data that the per capita rate of youth gun deaths in our community is 5x the national average. And when you look at the data further, accidental gun deaths are by far the largest type of gun death among youth in Patriotsville, accounting for 60% of all youths who die in our community each year. This is unacceptable and senseless heartbreak that’s ripping our community apart by the seams.

I know we can do better - we can and we will eliminate all accidental shooting deaths in Patriotsville within 5 years. In five years, let’s have the front page stories about our youth be for their achievements and service to our community rather than their obituaries. By 2027 our vision is no more funerals for young people killed by accidental shootings. We should be celebrating graduations and growth, not lives lost too early from entirely preventable means.

We know there are other types of gun violence in our community, and those senseless death are no less important than accidental shootings. But we are choosing to focus on accidental shootings because of how severe the problem is and because we have the capability and the partnerships already in place to make tangible progress. As we start to bend the trajectory of accidental shootings, we will turn our focus to the next most prevalent form of gun violence in our community: domestic disputes that turn deadly.

Our community has tried to have gun buybacks and free distribution of gun locks before. For years we have done these things and nothing has changed. So we started to do more intentional research into the data, the scholarship, and best practices, yes. But more importantly, we started to talk directly with the families who have lost children to accidental shootings and those who have had near misses.

By trying to deeply understand the people we want to influence, we learned two very important things. First, we learned that the vast majority of accidental shootings in Patriotsville have victims between the ages of 2 and 6. This means, we have to focus on influencing the parents and caregivers of children between the ages of 2 and 6.

And two, we learned that in the vast majority of cases, those adult owners of the firearms had access to gun locks and wanted to use them, but just never got around to it.

What we realized the more we talked with people and looked into the data, is that gun locks could work to reduce accidental shootings and that access wasn’t an issue - we just needed to get people to understand how to use gun locks and realize that it wasn’t difficult or a significant deterrent to the use of the firearm in an emergency.

So what we intend to do is work with day care providers to help influence the behavior of parents and caregivers of children who are in kindergarten or younger. We’re going to partner with the gun shop owners in town who desperately want their firearms to be stored safely. And we’re going to help families have all the resources they need to create a system within their entire home of securing firearms.

We’re proud to announce the “Lock It Twice” program here today in Patriotsville. There are many key roles in this plan. Gun shop owners and local hunting clubs are going to have public demonstrations on how to use gun locks and help citizens practice to see just how easy it is to use them. Early childhood educators and the school district are going to create a conversation guide for teachers to discuss with parents during parent teacher conferences. And finally, the local carpenters union, is going to help folks to make sure there are locks on the doors of the primary rooms where guns are kept. The community foundation is going to fund a program where families can get a doorknob replaced in their home for free.

We’re all coming together to end accidental shootings in our community once and for all - and we’re going to do it creatively and innovatively, because we know marketing campaigns and free gun locks don’t actually work unless they’re executed as part of a comprehensive strategy. To this end, we’re committing $2 Million of general fund dollars over the next five years to get this done - we are committed as a government and we invite any others committed to the goal to join us with their time, their talent, or financial backing.

Finally, I’d like to thank the leadership team of our local NRA chapter and Sportsmans’ club who helped us get access to their members and really understand the problem and the challenge in a deep and intimate way. We couldn’t have come up with this solution without their help.

We have said for so long that the time is now. And the time finally is now - we are focused, and we’re committed to ending accidental shootings in our community. In a few short years, if we work together, we know we can end these senseless deaths and never have a funeral for a young person accidentally shot and killed in this community ever again.

Unpacking the key elements of the two-pager of strategic intent

Again, the statement above is entirely an illustration and entirely made up. Heck, it’s not even the best writing I’ve ever done!

But even if it’s not true (or perfect) it’s helpful to have an example of what clearly articulated strategy and intent can look like. I’ve picked it apart section by section below. A narrative of strategic intent can be distilled into 10 elements. Literally 10 bullet points on a paper could be enough to start.

Element 1: Acknowleding the problem - “too many people are dying of gunshot wounds”

The first step is acknowledging the problem and communicating why change is even needed. This question of “why” is under-articulated in almost any organization or on any project I’ve ever been a part of. This is absolutely essential because change requires discretionary effort and almost nobody gives that discretionary effort unless they understand why it’s needed and why it matters.

Element 2 - The Big, Hairy, Audacious, Goal (BHAG): “we will eliminate all accidental shooting deaths in Patriotsville within 5 years”

The second step is to set a goal - a big one that’s meaningfully better than the status quo. This question of “for what” is essential to keep all parties focused on the same outcome. What’s critical for the goal is that it has to be specific, simple, and outcomes-based. Vague language does the team no good because unless the goal is objective, all parties will lie to themselves about progress. It should go without saying, but I’ll say it anyway: it’s practically impossible to lead collective action without a clear goal.

Element 3 - The Statement of Vision: “no more funerals for young people killed by accidental shootings”

The third element helps people more deeply understand what the goal means in day to day life. The vision is a deepening of detail on the question of “what”.

Having an understanding of the aspirational future world helps everyone understand success and what the future should feel like. This is important for two reasons: 1) it clarifies the goal further by giving it sensory detail, and, 2) it makes the mission memorable and inspiring.

In reality, the change leader needs to articulate the vision, in vivid sensory detail, over and over and with much more fidelity than I’ve done in this two-pager. Think of the vision statement I’ve listed in the two-pager as the headline with much more detail required behind the scenes and with constant frequency over the course of the journey.

Element 4 - Where to Play: “But we are choosing to focus on accidental shootings because of how severe the problem is and because we have the capability and the partnerships already in place to make tangible progress”

Where to play is one of the foundational questions of business strategy. The idea is that there are too many possible domains to play in and every enterprise needs to double down and focus instead of trying to do everything for all people. This isn’t a question of “what” as much as it is a question of “what are we saying no to.”

In the case of Patriotsville, the two-pager describes the reasons why the community should focus on accidental shootings (severity and existing capabilities / partnerships) and something important that the community is saying no to (domestic violence shootings). It’s essential to clearly articulate what the team is saying no to so that everyone doubles down and focuses limited resources on the target. Trying to “boil the ocean” is the surest way to achieve nothing.

Element 5 - Identifying the target: “we have to focus on influencing the parents and caregivers of children between the ages of 2 and 6”

There’s substantial time spent describing how the change team is focusing on the specific people they’re trying to influence, parents and caregivers of children aged 2-6. Identifying this specific segment is important, and an example of the ‘for who” question. Who are we trying to serve? Who are we not? What do they need? Without this, there is no possibility of true focus. Defining who it’s for is an essential rejoinder to the “where to play” question.

Element 6 - Deep Empathy and Understanding: “By trying to deeply understand the people we want to influence, we learned two very important things”

The two-pager talks about the deep observation and understanding of the “consumer” that the team took the time to do. This yielded some critical insights on how to do something that actually works.

There’s a whole discipline on UX (User experience) and CX (Customer experience), so I won’t try to distill it down in a few sentences - but a broader point remains. To change the behavior of someone or to serve someone, you have to really understand, deeply, what they want and need. When problems are hard, the same old stuff doesn’t work. To find what does work, the team has to listen and then articulate the key insights they learned to everyone else so that everyone else knows what will work, too.

Element 7 - How to Win: “we realized that gun locks could work to reduce accidental shootings and that access wasn’t an issue - we just needed to get people to understand how to use gun locks, and realize that it wasn’t difficult or a significant deterrent to the use of the firearm in an emergency”

“How to win” is the second of the foundational questions asked in business strategy. It raises the question of “how.” Of all the possible paths forward, which ones are we going to pursue, and which are we going to ignore? That’s what this element describes.

Because again, just like the “where to play” question, we can’t do every implementation of every strategy and tactic. We have to make choices and be as intentional as possible as to what we will do, what we won’t, and our reasons why.

By articulating “how to win” clearly, it keeps the team focused on what we believe will work and what we believe is worth throwing the kitchen sink at, so to speak. Execution is hard enough, even without the team diluting its execution across too broad a set of tactics.

What I would add, is that we don’t always get the how right the first time. We have to constantly pause, learn, pivot, and then rearticulate the how once we realize our plan isn’t going to work - the first version of the plan never does.

Element 8 - Everyone’s Role: “There are many key roles in this plan”

Element 8 gets at the “who” question. Who’s going to do this work? What’s everyone’s important role? What’s everyone’s job and responsibility?

Everyone needs to know what’s expected of them. And quite frankly, if a change leader doesn’t ask people to do something, they won’t. It seems obvious, but teams I’ve been on haven’t actually requested help. Heck, I’ve even led initiatives where I’ve just assumed everyone knows what to do and then been surprised when nobody on the team acts differently. That’s a huge mistake that’s entirely preventable.

Element 9 - Credible Commitment: “To this end, we’re committing $2 Million of general fund dollars over the next five years to get this done”

Especially when it comes to hard problems, many people will wait to ensure that their effort is not a waste of time. Making a credible commitment that the change leader is going to stick with the problem nudges stakeholders to commit. By putting some skin in the game and being vocal about it publicly, a credible commitment answers the “are you really serious” question that many skeptics have when a change leader announces a Big, Hairy, Audacious, Goal.

Element 10 - The problem is the enemy: “Finally, I’d like to thank the leadership team of our local NRA chapter and Sportsmans’ club who helped us”

In my years, many ambitious teams get in their own way because they succumb to ego, blame, and infighting. Right away, it’s essential to make sure everyone knows that the problem is the enemy.

In this case, I’ve shared an example of how it’s possible to take seemingly difficult stakeholders, show them respect, and bring them into the fold. How powerful would it be if a group commonly thought of as an obstacle to ending gun violence (the gun lobby) was actually part of the solution and the change leader praised them? That sort of statement would prevent finger pointing and resistance to the pursuit of the vision. If the gun lobby is helping prevent gun violence, how could anyone else not fall in line and trust the process?

Conclusion

I desperately want to see an end to gun violence in my lifetime. It’s senseless. And honestly, I think everyone engaged in gun violence prevention has good intentions.

But we shouldn’t expect to solve the problem if we don’t take the time to understand it, articulate it in concrete terms, and communicate the vision clearly to everyone who needs to be part of solving it.

As one of the few people who have lived in both worlds - violence prevention and business strategy - I strongly believe tools from the corporate strategy and CX worlds have something valuable to offer in this regard.

Photo by Remy Gieling on Unsplash

In-sourcing Purpose

At work, we shouldn’t depend on our companies to find purpose and meaning for us. We have the capability to find it for ourselves.

When it comes to being a husband and father, doing more than just the bare minimum is not difficult. At home, I want to do much more than mail it in.

The obvious reason is because I love my family. I care about them. I find joy in suffering which helps them to be healthy and happy. I believe that surplus is an essential ingredient to making an impactful contribution, and with my family I give up the surplus I have easily, perhaps even recklessly. I love them, after all.

Photo Credit: Unsplash @krisroller

And yet, love doesn’t explain this fully. The ease with which I put in effort at home taps into a deeper well of motivation and purpose.

With Robyn, our marriage is driven by a deeper purpose than having a healthy relationship, or perhaps even the commitment to honoring our vows. We find meaning in building something, in our case a marriage, that could last thousands of years or an eternity if there is a God that permits it. We’re trying to build something that could last until the end of time, until there is nothing of us that exists - in this world or beyond. We’re trying to make a marriage that’s more durable than “as long as we both shall live.” We find meaning in that.

Though we’ve never talked about it explicitly, I think we also find meaning in trying to have a marriage that’s based on equality and mutual respect. It’s as if we’re trying to be a beacon for what a truly equal marriage could look like. I don’t think we’ve succeeded in this yet; I’m certain that despite our best efforts, Robyn still bears an unequal portion of our domestic responsibilities. But yet, we try to find that elusive, perfectly equal, and mutually respectful marriage and we find meaning in that pursuit.

As a father, too, I find purpose and meaning that exeeceds the strong love and attachment I have with my children. I find it so inspiring to be part of something that spans generations and millennia. I am merely the latest steward to pass down the love, knowledge, and virtues of our ancestors. I find it humbling to be part of a lineage that started many centuries ago, and that will hopefully exist for many centuries in the future. Being one, single, link in this longer chain moves me, deeply.

I also believe deeply in a contribution to the broader community, to human society itself. And there too, fatherhood intersects. Part of my responsibility to humanity, I believe, is to raise children that are a net force for goodness - children that because of their actions make the world feel more trustworthy and vibrant. Through my own purification as a father, I can pass a purer set of values and integrity to our children, and accelerate - ever so slightly - the rate at which the arc of humanity and history bends towards justice. This is so lofty and so abstract, but yet, I find meaning in this.

These sources of deep purpose make it easy, trivial even, to put forth an amount of energy toward being a husband and father that a 16 year old me would find incomprehensible.

Finding this deep and durable source of purpose has been harder in my career, though I’m realizing it might have been hidden in plain sight all along.

I often felt maligned when I worked at Deloitte, especially when it felt like the ultimate end product of my time was simply making wealthy partners wealthier. At least Deloitte was a culture of kind people, and also had a sincere commitment to the community - I found some meaning in that.

But in retrospect, I think I missed the point. Deloitte, after all, is a huge consultancy. Its clients are some of the largest and most influential enterprises in the history of the world. Deloitte also produces research that is read by leaders and managers across the world. The amount of lives affected by Deloitte, through its clients, is probably in the billions. While I was there, I had an opportunity - albeit a small one - to affect the managerial quality of the world’s largest companies. That is incredibly meaningful. In retrospect, I wish I would’ve remembered that when I was toiling away on client projects, wishing I was doing anything else to earn a living.

While working in City government, sources of purpose and meaning were easier to find. It was easy to give tremendous effort, for example, toward reducing murders and shootings. I was a civilian appointee, and relatively junior at that - but we were still saving lives, literally. But even beyond that, I found meaning in something more humble - I had the honor and privilege of serving my neighbors. That phrase, serving my neighbors, still wells my eyes up in tears. What a gift it was to serve.

And now, I work in a publicly traded company. We manufacture and sell furniture. These are not prima facie sources of deep meaning and purpose. In the day-to-day, week-to-week, grind I often find myself in the same mindset as I was at Deloitte, asking myself questions like, why am I here, or, am I wasting my time?

And yet, I also realize that with hindsight I would probably realize that meaning and foundation on which to assemble a strong sense of purpose was always there, had I cared enough to look for it.

Why, I have been thinking this week, is it so easy to to find meaning purpose at home, but so difficult at work? There must be a deep well of meaning from which to draw, hidden in plain sight, why can’t I find it?

At home, I realized, we are free. We have nobody ruling us, but us. We are free to explore and think and make our family life what we wish it to be. I think and talk openly with Robyn about our lives. We reflect and grapple with our lived experiences and take it upon ourselves to make meaning from it. We aren’t waiting for anyone else to tell us what our purpose as partners, parents, or citizens.

In a way, at home, we in-source our deliberations of purpose. We literally do it “in house”. We know it is is on us to make meaning of our marriage and our roles as parents, so Robyn and I do it. We have, in effect in-source our search for meaning and purpose.

At work, I have done the opposite.

In my career, I have outsourced my search for meaning and purpose. I’ve waited, without realizing it, for senior executives to tell me why what we’re doing matters. I’ve whined, in my head at least, when the mission statements and visions of companies I’ve worked for - either as an employee or as a consultant - have been vacuous or sterile.

In retrospect, I’ve freely relinquished my agency to create meaning and purpose to the enterprises for which I have worked. What a terrible mistake that was. Why was I waiting for someone else to find purpose for me, when I could’ve been creating it for myself all along?

When companies do articulate statements of purpose well, it is powerful and I appreciate it. My current company has a purpose statement, for example, and it does resonate with me. I’m glad we have one.

But yet, that’s not enough. To really give a tremendous amount of discretionary effort at work, I need to believe in something much more specific to me. After all, even the best statement of purpose put out by a company is, by design, something meant to appeal to tens of thousands of people. I shouldn’t expect a corporate purpose statement to ignite my inspiration, such an expectation is not reasonable or fair. No company will ever write a purpose statement that’s specifically for me, nor should they.

Rather than outsource my search for meaning and purpose, I’ve realized I need to in-source it. Perhaps with questions like these:

What makes my job and working as part of this enterprise special? What’s something about it that’s so valuable and important that I want to put my own ego, career development, and desire to be promoted aside and contribute to the team’s goal? What can I find meaning in and be proud of? What about being here makes me want to put effort in beyond the bare minimum?

Like I said, I work for a furniture company - certainly not something glamorous or externally validated . And yet, there can be so much meaning and purpose in it, if I choose to see it.

We are in people’s homes and we have this ability to rehabilitate people’s bodies and minds. We create something that brings comfort to other people and for every family movie night and birthday party - the biggest and smallest moments in the lives of our customers and their families, we are there. That’s worth putting in a little extra for.

And we’re a Michigan company, headquartered in a relatively small town. I get to be part of a team bringing wealth, prosperity, and respect to our State. I can’t tolerate it when people from elsewhere in the country snub their noses at Michigan, calling us a “fly over” state. I find meaning in that competition to be an outstanding enterprise - why not have the industry leader in furniture manufacturing and retailing be a Michigan company?

Without even considering the meaning and joy I find in creating high-performing teams that unleash people’s talent, there is so much meaning and purpose that’s hidden in plain sight - even at a furniture company. But that meaning is nearly impossible to find unless we stop being dependent on others to create meaning for us - we have to bring the search for purpose back in house.

How interesting might it be if everyone on the team created their own purpose statement, rather than depending on the enterprise to provide one for them? What if companies helped their employees create their own purpose statement instead of making one for them? I think such an approach would be interesting and, no pun intended, meaningful.

Death is glue

Death is one of the few things every single person on this Earth has in common. What if our politics were informed by the struggle with death we all have?

There are so many issues and problems that we need our politics to alleviate. Everything from the economy, to health, to environment, to violence. So how do we organize it all, what do we do first?

To me, the most profound and impactful thing that will happen to any of us is death. Death is one of, or perhaps the only thing, we all truly have in common. We all grapple with it. We will all face it. Death is non-discriminatory in that way. Death binds us together. Death is glue.

If death is glue, I’ve wondered what a political framework that acknowledges and is informed by the profundity of death would be. To me, three principles emerge that could help our politics sharpen its focus on what matters most.

The first organizing principle is to prevent senseless death. A senseless death is one that does not have to happen, given what is and is not in our control as a species, right now. Death is inevitable and basically nobody wants to die, so let’s prevent (or at least delay) the deaths we can. So that means we should focus on these data, figure out which causes of death are truly senseless, and address all the underlying determinants of them.

Before we do anything else, lets prevent senseless death - whether it’s from war, from preventable disease, from gun violence, or something else.

The next principle is to prevent a senseless life. What is a senseless life? That’s a difficult, multi-faceted question. But I think the Gallup Global Emotions report has data that are onto something. They ask questions about positive or negative experiences and create an index from the answers - surveying on elements like whether someone is well rested, feels respected, or feels sadness. What we could do is understand the data, geography by geography, to understand why different populations feel like life is worth (or not worth) living. Then, we solve for the underlying determinants.

There are so many reasons that someone may feel a senseless life, these challenges are probably best understood locally or through the lens of different types of “citizen segments” like “young parents”, “the elderly”, “small business owners”, or “rural and agriculturally-focused”.