Crafting a Resident-Centric CX Strategy for Michigan

What might a resident-centric strategy to attract and retain talent look like for Michigan?

Last week, I shared an idea about one idea to shape growth, talent development, and performance in Michigan through labor productivity improvements. This week, I’ve tried to illustrate how CX practices can be used to inform talent attraction and retention at the state level.

The post is below, and it’s a ChatGPT write-up of an exercise I went through to rapidly prototype what a CX approach might actually look like. In the spirit of transparency, there are two sessions I had with ChatGPT: this this one on talent retention. I can’t share the link for the one on talent attraction because I created an image and sharing links with images is apparently not supported (sorry). It is similar.

There are a few points I (a human) would emphasize that are important subtleties to remember.

Differentiating matters a ton. As the State of Michigan, I don’t think we can win on price (i.e., lower taxes) because there will always be a state willing to undercut us. We have to play to our strengths and be a differentiated place to live.

Focus matters a ton. No State can cater to everyone, and neither can we. We have to find the niches and do something unique to win with them. We can’t operate at the “we need to attract and retain millennials and entrepreneurs” level. Which millennials and which entrepreneurs? Again, we can’t cater to everyone - it’s too hard and too expensive. It’s just as important to define who we’re not targeting as who we are targeting.

Transparency matters a ton. As a State, the specific segments we are trying to target (and who we’re deliberately not trying to targets) need to be clear to all stakeholders. The vision and plan needs to be clear to all stakeholders (including the public) so we can move toward one common goal with velocity. By being transparent on the true set of narrow priorities, every organization can find ways to help the team win. Without transparency, every individual organization and institution will do what they think is right (and is best for them as individual organizations), which usually leads to scope creep and a lot of little pockets of progress without any coordination across domains. And when that happens, the needle never moves.

It seems like the State of Michigan is doing some of this. A lot of the themes from ChatGPT are ones I’ve heard before. Which is great. What I haven’t heard are the specific set of segments to focus on or what any of the data-driven work to create segments and personas was. If ChatGPT can come up with at least some relatively novel ideas in an afternoon, imagine what we could accomplish by doing a full-fidelity, disciplined, data-driven, CX strategy with the smartest minds around growth, talent, and performance in the State. That would be transformative.

I’d love to hear what you think. Without further ado, here’s what ChatGPT and I prototyped today around talent attraction and retention for the State of Michigan.

—

Introduction: Charting a New Course for Michigan

In an age where competition for talent and residents is fierce among states, Michigan stands at a crossroads. To thrive, it must reimagine its approach to attracting and retaining residents, and this is where Customer Experience (CX) Strategy, intertwined with insights from population geography, becomes vital. Traditionally a business concept, CX Strategy in the context of state governance is about understanding and catering to the diverse needs of potential and current residents. It's about seeing them not just as citizens, but as customers of the state, with unique preferences and aspirations.

Understanding CX Strategy in Population Geography

CX Strategy, at its essence, involves tailoring experiences to meet the specific needs and desires of your audience. For a state like Michigan, it means crafting policies, amenities, and environments that resonate with different demographic groups. Population geography provides a lens to understand these groups. It involves analyzing why people migrate: be it for job opportunities, better quality of life, or cultural attractions. This understanding is crucial. For instance, young professionals might be drawn to vibrant urban environments with tech job prospects, while retirees may prioritize peaceful communities with accessible healthcare. Michigan, with its rich automotive history, beautiful Great Lakes, and growing tech scene, has much to offer but needs a focused approach to highlight these strengths to different groups.

Applying CX Strategy: Identifying Target Segments

The first step in applying a CX Strategy is identifying who Michigan wants to attract and retain. This involves delving into demographic data, economic trends, and social patterns. Creating detailed personas based on this data helps in understanding various needs and preferences. For instance, a tech entrepreneur might value a supportive startup ecosystem, while a nature-loving telecommuter may prioritize scenic beauty and a peaceful environment for remote work. These insights lead to targeted strategies that are more likely to resonate with each group, ensuring efficient use of resources and increasing the effectiveness of Michigan's efforts in both attracting and retaining residents.

In the next section, we'll explore the importance of differentiation in attraction and retention strategies, and delve into the specific segments that Michigan should focus on. Stay tuned for a detailed look at how Michigan can leverage its unique attributes to create a compelling proposition for these key resident segments.

Importance of Differentiation in Attraction and Retention

Differentiation is crucial in the competitive landscape of state-level attraction and retention. It’s about highlighting what makes Michigan unique and aligning these strengths with the specific needs of targeted segments. For attraction, it might mean showcasing Michigan’s burgeoning tech industry to young professionals or its serene natural landscapes to nature enthusiasts. For retention, it involves ensuring that these segments find ongoing value in staying, like continuous career opportunities for tech professionals or maintaining pristine natural environments for outdoor lovers.

In focusing on segments like automotive innovators or medical researchers, Michigan can leverage its historic strengths and modern advancements. By tailoring experiences to these specific groups, the state can stand out against competitors, making it not just a place to move to but a place where people want to stay and thrive.

Overlap and Distinction in Attraction and Retention Strategies

The overlap and distinctions between attracting and retaining segments offer nuanced insights. Some segments, like tech and creative professionals, show significant overlap in both attracting to and retaining in urban settings like Detroit. This indicates that strategies effective in drawing these individuals to Michigan may also foster their long-term satisfaction. However, for segments with minimal overlap, such as medical researchers (attraction) and sustainable farmers (retention), strategies need to be distinct and targeted to their unique needs and lifestyle preferences.

Successful implementation teams will use these insights to create nuanced strategies for each segment. Avoiding a one-size-fits-all approach and recognizing the different motivations between someone considering moving to Michigan and someone deciding whether to stay is key. The primary pitfall to avoid is neglecting the distinct needs of each segment, which could lead to ineffective strategies that neither attract nor retain effectively.

Deep Dive into Experience Enhancements

Let’s delve into two specific segments: nature-loving telecommuters for attraction and tech and creative young professionals in Detroit for retention. For the nature-loving telecommuter, Michigan can offer unique experiences that blend the tranquility of its natural landscapes with the connectivity needed for effective remote work. Imagine "remote worker eco-villages" scattered across Michigan’s scenic locations, equipped with state-of-the-art connectivity and co-working spaces, set against the backdrop of Michigan's natural beauty. This not only caters to their desire for a serene work environment but also positions Michigan as a leader in innovative remote working solutions.

For tech and creative young professionals in Detroit, the strategy should be about fostering a dynamic urban ecosystem that offers continuous growth opportunities and a thriving cultural scene. Initiating a Detroit Tech and Arts Festival could serve as an annual event, bringing together tech innovators, artists, and entrepreneurs. This festival, coupled with collaborative workspaces and networking hubs, would not only retain existing talent but also attract new professionals looking for a vibrant, collaborative, and innovative urban environment.

Conclusion: Michigan’s Path Forward

Michigan is uniquely positioned to become a beacon for diverse talents and lifestyles. By adopting a resident-centric CX Strategy, informed by population geography, Michigan can tailor its offerings to attract and retain a dynamic population. It’s about moving beyond generic policies to creating experiences and opportunities that resonate with specific segments. The call to action is clear: Let's embrace innovation, leverage our unique strengths, and build a Michigan that’s not just a place on a map, but a destination of choice for a vibrant and diverse community. With these strategies, Michigan won’t just attract new residents – it will inspire them to stay, contribute, and flourish.

Attraction Segments Table:

Retention Segments Table:

Corporate Strategy, CX, and the end of gun violence

Techniques from the disciplines of corporate strategy and customer experience can help define the problem of gun violence clearly and hasten its end.

What gut punches me about gun violence, beyond the acts of violence themselves, is not that we’ve seemed to make little progress in ending it. What grates me is that we shouldn’t expect to make progress. We shouldn’t expect progress because in the United States, generally speaking, we haven’t actually done the work to define the problem of gun violence clearly enough to even attempt solving it with any measure of confidence.

Gun violence is an incredibly difficult problem to solve, it’s layered, it’s complex, and the factors that affect gun violence are intertwined in knots upon knots across the domains of poverty, justice, health, civil rights, land use, and many others.

Moreover, it’s hard to prevent gun violence because different types of violence are fundamentally different, requiring different strategies and tactics. What it takes to prevent gang violence, for example, is extremely different from what it takes to prevent mass shootings. Forgive my pun, but in gun violence prevention, there’s no silver bullet.

I know this because I lived it and tried to be a small part in ending gun violence in Detroit. I partnered with people across neighborhoods, community groups, law enforcement, academia, government, the Church, foundations, and the social sector on gun violence prevention - the best of the best nationwide - when I worked in City Government, embedded in the equivalent of a special projects unit within the Detroit Police Department.

Preventing gun violence is the hardest challenge I’ve ever worked on, by far.

Just as I’ve seen gun violence prevention up close - I’ve also worked in the business functions of corporate strategy and customer experience (CX) for nearly my entire career - as a consultant at a top tier firm, as a graduate student in management, as a strategy professional in a multi-billion dollar enterprise, and as a thinker that has been grappling with and publishing work on the intricacies of management and organizations for over 15 years.

(Forgive me for that arrogant display of my resume, the internet doesn’t listen to people without believing they are credentialed).

I know from my time in Strategy and CX that difficult problems aren’t solved without focus, the discipline to make the problem smaller, accepting trade-offs, and empathizing deeply with the people we are trying to serve and change the behavior of.

This is why how we approach gun violence in the United States, generally speaking, grates me. Very little of the public discourse on gun violence prevention - outside of very small pockets, usually at the municipal level - gives me faith that we’re committed to the hard work of focusing, making the problem smaller, accepting trade-offs and empathizing deeply with the people - shooters and victims - we are trying to change the behavior of.

If I had to guess, there are probably less than 100 people across the country who have lived gun violence prevention and business strategy up close, and I’m one of them. The solutions to gun violence will continue to be elusive, I’m sure - just “applying business” to it won’t solve the problem.

However, all problems, especially elusive ones like gun violence, are basically impossible to solve until they are defined clearly and the strategy to achieve the intended outcome is focused and clearly communicated. To understand and frame the problem of gun violence, approaches from strategy and CX are remarkably helpful.

This post is my pitch and the simplest playbook I can think of for applying field-tested practices from the disciplines of strategy and CX to gun violence prevention. My hope is that by applying these techniques, gun violence could become a set of solvable problems. Not easy, but solvable nonetheless.

If you can’t put it briefly and in writing the strategy isn’t good enough

The easiest, low-tech, test of a strategy, is whether it can be communicated in narrative form, in one or two pages. If someone trying to lead change can do this effectively, it probably means the strategy and how it’s articulated is sound. If not, that change leader should not expect to achieve the result they intend.

The statement that follows below is entirely made up, but it’s an illustration of what clear strategic intent can look like. I’ve written it for the imaginary community of “Patriotsville”, but the framework I’ve used to write it could be applied by any organization, for any transformation - not just an end to gun violence. Further below I’ll unpack the statement section by section to explain the underlying concepts borrowed from business strategy and CX and some ideas on how to apply them.

Instead of platitudes like, “we need change” or “enough is enough” or “the time is now”, imagine if a change leader trying to end gun violence made a public statement closer to the one below. Would you have more or less confidence in your community’s ability to end gun violence than you do now?

Two-Pager of Strategic Intent to End Gun Violence in Patriotsville

We have a problem in Patriotsville, too many young people are dying from gunshot wounds. We know from looking at the data that the per capita rate of youth gun deaths in our community is 5x the national average. And when you look at the data further, accidental gun deaths are by far the largest type of gun death among youth in Patriotsville, accounting for 60% of all youths who die in our community each year. This is unacceptable and senseless heartbreak that’s ripping our community apart by the seams.

I know we can do better - we can and we will eliminate all accidental shooting deaths in Patriotsville within 5 years. In five years, let’s have the front page stories about our youth be for their achievements and service to our community rather than their obituaries. By 2027 our vision is no more funerals for young people killed by accidental shootings. We should be celebrating graduations and growth, not lives lost too early from entirely preventable means.

We know there are other types of gun violence in our community, and those senseless death are no less important than accidental shootings. But we are choosing to focus on accidental shootings because of how severe the problem is and because we have the capability and the partnerships already in place to make tangible progress. As we start to bend the trajectory of accidental shootings, we will turn our focus to the next most prevalent form of gun violence in our community: domestic disputes that turn deadly.

Our community has tried to have gun buybacks and free distribution of gun locks before. For years we have done these things and nothing has changed. So we started to do more intentional research into the data, the scholarship, and best practices, yes. But more importantly, we started to talk directly with the families who have lost children to accidental shootings and those who have had near misses.

By trying to deeply understand the people we want to influence, we learned two very important things. First, we learned that the vast majority of accidental shootings in Patriotsville have victims between the ages of 2 and 6. This means, we have to focus on influencing the parents and caregivers of children between the ages of 2 and 6.

And two, we learned that in the vast majority of cases, those adult owners of the firearms had access to gun locks and wanted to use them, but just never got around to it.

What we realized the more we talked with people and looked into the data, is that gun locks could work to reduce accidental shootings and that access wasn’t an issue - we just needed to get people to understand how to use gun locks and realize that it wasn’t difficult or a significant deterrent to the use of the firearm in an emergency.

So what we intend to do is work with day care providers to help influence the behavior of parents and caregivers of children who are in kindergarten or younger. We’re going to partner with the gun shop owners in town who desperately want their firearms to be stored safely. And we’re going to help families have all the resources they need to create a system within their entire home of securing firearms.

We’re proud to announce the “Lock It Twice” program here today in Patriotsville. There are many key roles in this plan. Gun shop owners and local hunting clubs are going to have public demonstrations on how to use gun locks and help citizens practice to see just how easy it is to use them. Early childhood educators and the school district are going to create a conversation guide for teachers to discuss with parents during parent teacher conferences. And finally, the local carpenters union, is going to help folks to make sure there are locks on the doors of the primary rooms where guns are kept. The community foundation is going to fund a program where families can get a doorknob replaced in their home for free.

We’re all coming together to end accidental shootings in our community once and for all - and we’re going to do it creatively and innovatively, because we know marketing campaigns and free gun locks don’t actually work unless they’re executed as part of a comprehensive strategy. To this end, we’re committing $2 Million of general fund dollars over the next five years to get this done - we are committed as a government and we invite any others committed to the goal to join us with their time, their talent, or financial backing.

Finally, I’d like to thank the leadership team of our local NRA chapter and Sportsmans’ club who helped us get access to their members and really understand the problem and the challenge in a deep and intimate way. We couldn’t have come up with this solution without their help.

We have said for so long that the time is now. And the time finally is now - we are focused, and we’re committed to ending accidental shootings in our community. In a few short years, if we work together, we know we can end these senseless deaths and never have a funeral for a young person accidentally shot and killed in this community ever again.

Unpacking the key elements of the two-pager of strategic intent

Again, the statement above is entirely an illustration and entirely made up. Heck, it’s not even the best writing I’ve ever done!

But even if it’s not true (or perfect) it’s helpful to have an example of what clearly articulated strategy and intent can look like. I’ve picked it apart section by section below. A narrative of strategic intent can be distilled into 10 elements. Literally 10 bullet points on a paper could be enough to start.

Element 1: Acknowleding the problem - “too many people are dying of gunshot wounds”

The first step is acknowledging the problem and communicating why change is even needed. This question of “why” is under-articulated in almost any organization or on any project I’ve ever been a part of. This is absolutely essential because change requires discretionary effort and almost nobody gives that discretionary effort unless they understand why it’s needed and why it matters.

Element 2 - The Big, Hairy, Audacious, Goal (BHAG): “we will eliminate all accidental shooting deaths in Patriotsville within 5 years”

The second step is to set a goal - a big one that’s meaningfully better than the status quo. This question of “for what” is essential to keep all parties focused on the same outcome. What’s critical for the goal is that it has to be specific, simple, and outcomes-based. Vague language does the team no good because unless the goal is objective, all parties will lie to themselves about progress. It should go without saying, but I’ll say it anyway: it’s practically impossible to lead collective action without a clear goal.

Element 3 - The Statement of Vision: “no more funerals for young people killed by accidental shootings”

The third element helps people more deeply understand what the goal means in day to day life. The vision is a deepening of detail on the question of “what”.

Having an understanding of the aspirational future world helps everyone understand success and what the future should feel like. This is important for two reasons: 1) it clarifies the goal further by giving it sensory detail, and, 2) it makes the mission memorable and inspiring.

In reality, the change leader needs to articulate the vision, in vivid sensory detail, over and over and with much more fidelity than I’ve done in this two-pager. Think of the vision statement I’ve listed in the two-pager as the headline with much more detail required behind the scenes and with constant frequency over the course of the journey.

Element 4 - Where to Play: “But we are choosing to focus on accidental shootings because of how severe the problem is and because we have the capability and the partnerships already in place to make tangible progress”

Where to play is one of the foundational questions of business strategy. The idea is that there are too many possible domains to play in and every enterprise needs to double down and focus instead of trying to do everything for all people. This isn’t a question of “what” as much as it is a question of “what are we saying no to.”

In the case of Patriotsville, the two-pager describes the reasons why the community should focus on accidental shootings (severity and existing capabilities / partnerships) and something important that the community is saying no to (domestic violence shootings). It’s essential to clearly articulate what the team is saying no to so that everyone doubles down and focuses limited resources on the target. Trying to “boil the ocean” is the surest way to achieve nothing.

Element 5 - Identifying the target: “we have to focus on influencing the parents and caregivers of children between the ages of 2 and 6”

There’s substantial time spent describing how the change team is focusing on the specific people they’re trying to influence, parents and caregivers of children aged 2-6. Identifying this specific segment is important, and an example of the ‘for who” question. Who are we trying to serve? Who are we not? What do they need? Without this, there is no possibility of true focus. Defining who it’s for is an essential rejoinder to the “where to play” question.

Element 6 - Deep Empathy and Understanding: “By trying to deeply understand the people we want to influence, we learned two very important things”

The two-pager talks about the deep observation and understanding of the “consumer” that the team took the time to do. This yielded some critical insights on how to do something that actually works.

There’s a whole discipline on UX (User experience) and CX (Customer experience), so I won’t try to distill it down in a few sentences - but a broader point remains. To change the behavior of someone or to serve someone, you have to really understand, deeply, what they want and need. When problems are hard, the same old stuff doesn’t work. To find what does work, the team has to listen and then articulate the key insights they learned to everyone else so that everyone else knows what will work, too.

Element 7 - How to Win: “we realized that gun locks could work to reduce accidental shootings and that access wasn’t an issue - we just needed to get people to understand how to use gun locks, and realize that it wasn’t difficult or a significant deterrent to the use of the firearm in an emergency”

“How to win” is the second of the foundational questions asked in business strategy. It raises the question of “how.” Of all the possible paths forward, which ones are we going to pursue, and which are we going to ignore? That’s what this element describes.

Because again, just like the “where to play” question, we can’t do every implementation of every strategy and tactic. We have to make choices and be as intentional as possible as to what we will do, what we won’t, and our reasons why.

By articulating “how to win” clearly, it keeps the team focused on what we believe will work and what we believe is worth throwing the kitchen sink at, so to speak. Execution is hard enough, even without the team diluting its execution across too broad a set of tactics.

What I would add, is that we don’t always get the how right the first time. We have to constantly pause, learn, pivot, and then rearticulate the how once we realize our plan isn’t going to work - the first version of the plan never does.

Element 8 - Everyone’s Role: “There are many key roles in this plan”

Element 8 gets at the “who” question. Who’s going to do this work? What’s everyone’s important role? What’s everyone’s job and responsibility?

Everyone needs to know what’s expected of them. And quite frankly, if a change leader doesn’t ask people to do something, they won’t. It seems obvious, but teams I’ve been on haven’t actually requested help. Heck, I’ve even led initiatives where I’ve just assumed everyone knows what to do and then been surprised when nobody on the team acts differently. That’s a huge mistake that’s entirely preventable.

Element 9 - Credible Commitment: “To this end, we’re committing $2 Million of general fund dollars over the next five years to get this done”

Especially when it comes to hard problems, many people will wait to ensure that their effort is not a waste of time. Making a credible commitment that the change leader is going to stick with the problem nudges stakeholders to commit. By putting some skin in the game and being vocal about it publicly, a credible commitment answers the “are you really serious” question that many skeptics have when a change leader announces a Big, Hairy, Audacious, Goal.

Element 10 - The problem is the enemy: “Finally, I’d like to thank the leadership team of our local NRA chapter and Sportsmans’ club who helped us”

In my years, many ambitious teams get in their own way because they succumb to ego, blame, and infighting. Right away, it’s essential to make sure everyone knows that the problem is the enemy.

In this case, I’ve shared an example of how it’s possible to take seemingly difficult stakeholders, show them respect, and bring them into the fold. How powerful would it be if a group commonly thought of as an obstacle to ending gun violence (the gun lobby) was actually part of the solution and the change leader praised them? That sort of statement would prevent finger pointing and resistance to the pursuit of the vision. If the gun lobby is helping prevent gun violence, how could anyone else not fall in line and trust the process?

Conclusion

I desperately want to see an end to gun violence in my lifetime. It’s senseless. And honestly, I think everyone engaged in gun violence prevention has good intentions.

But we shouldn’t expect to solve the problem if we don’t take the time to understand it, articulate it in concrete terms, and communicate the vision clearly to everyone who needs to be part of solving it.

As one of the few people who have lived in both worlds - violence prevention and business strategy - I strongly believe tools from the corporate strategy and CX worlds have something valuable to offer in this regard.

Photo by Remy Gieling on Unsplash

We Need To Understand Our Superpowers

We need to take the time to understand our superpowers, as individuals or as an organization, so we have the best chance to create surplus.

Surplus is created when something is more valuable than it costs in resources. Creating surplus is one of the keys to peace and prosperity.

Surplus ultimately comes from asymmetry. Asymmetry, briefly put, is when we have something in a disproportionately valuable quantity, relative to the average. This assymetry gives us leverage to make a disproportionally impactful contribution, and that creates surplus.

Let’s take the example of a baker, though this framework could apply to public service or family life. Some asymmetries, unfortunately, have a darker side.

Asymmetry of…

…capability is having the knowledge or skills to do something that others can’t (e.g., making sourdough bread vs. regular wheat).

…information gives the ability to make better decisions than others (e.g., knowing who sells the highest quality wheat at the best price).

…trust is having the integrity and reputation that creates loyalty and collaboration (e.g., 30 years of consistency prevents a customer from trying the latest fad from a competitor).

…leadership is the ability to build a team and utilize talent in a way that creates something larger than it’s parts (e.g., building a team that creates the best cafe in town).

…relationships create opportunities that others cannot replicate (e.g., my best customers introduce me to their brother who want to carry my bread in their network of 100 grocery stores).

…empathy is having the deep understanding of customers and their problems, which lead to innovations (e.g., slicing bread instead of selling it whole).

…capital is having the assets to scale that others can’t match (e.g., I have the money to buy machines which let me grind wheat into flour, reducing costs and increasing freshness).

…power is the ability to bend the rules in my favor (e.g., I get the city council to ban imports of bread into our town).

…status is having the cultural cachet to gain incremental influence without having to create any additional value (e.g., I’m a man so people might take me more seriously).

We need to understand our superpowers

So one of the most valuable things we can do in organizational life is knowing the superpowers which give us assymetry and doing something special with them. We need to take the time to understand our superpowers, as individuals or as an organization, so we have the best chance to create surplus.

And once we have surplus - whether in the form of time, energy, trust, profit, or other resources - we can do something with it. We can turn it into leisure or we can reinvest it in ourselves, our families, our communities, and our planet.

—

Addendum for the management / strategy nerds out there: To put a finer point on this, we also need to understand how asymmetries are changing. For example, capital is easier to access (or less critical) than it was before. For example, I don’t know how to write HTML nor do I have any specialized servers that help me run this website. Squarespace does that for me for a small fee every month. So access to capital assets and capabilities is less asymmetric than 25 years ago, at least in the domain of web publishing.

As the world changes, so does the landscape of asymmetries, which is why we often have to reinvent ourselves.

There’s a great podcast episode on The Knowledge Project where the guest, Kunal Shah, has a brief interlude on information asymmetry. Was definitely an inspiration for this post.

Source: Miguel Bruna on Unsplash

The Power of Thinking in Flywheels

Feedback loops are what underpin huge changes in our world. Understanding what Jim Collins dubbed “the flywheel effect” is essential learning for anyone trying to lead or change culture.

These are learnings I’ve had trying to apply flywheel thinking in my world, over the past 2-3 years. Flywheels have helped me to understand everything from business strategy, to management, to gun violence prevention, and even my own marriage.

There are two types of growth, generally speaking - linear growth and exponential growth. And I’m not just talking about for a corporation, but for teams, culture, families, and ourselves as individuals.

The problem with linear growth is diminishing marginal returns - once your market is saturated you have to spend more and more to get less and less. The problem with exponential growth is that it’s hard and also doesn’t last indefinitely. (Sustaining exponential growth is a topic for a different day.)

Jim Collins developed an interesting concept to make exponential growth less hard, which I find brilliant - the flywheel effect. Flywheels are basically a way of thinking about a feedback loop, deliberately. He explains it well in this podcast interview with Shane Parrish on the Knowledge Project. Some of the key takeaways for me were:

The goal of a leader is to remove friction from the flywheel, because once you get it turning, it builds momentum and starts moving faster and faster.

Each step of the flywheel has to be inevitable outcome of the previous step. Think: “If Step 1 happens, then Step 2 will naturally occur”

The key to harnessing flywheels aren’t a silver bullet or Big Bang initiative, it’s a deliberate process of understanding what creates value and building momentum - slowly at first, but then accelerating. To the outside it’s an overnight breakthrough, but to the inside it was a disciplined, iterative process to understand the flywheel, and reducing friction to get it cranking

I was introduced to this concept when I read Good to Great years ago, and was reintroduced to it before the Covid pandemic. Only recently has it started to click.

I’ve found flywheels to be a transformative way of thinking, both at work and in my real life. Here are a few examples of flywheels I’ve experienced and experimented with.

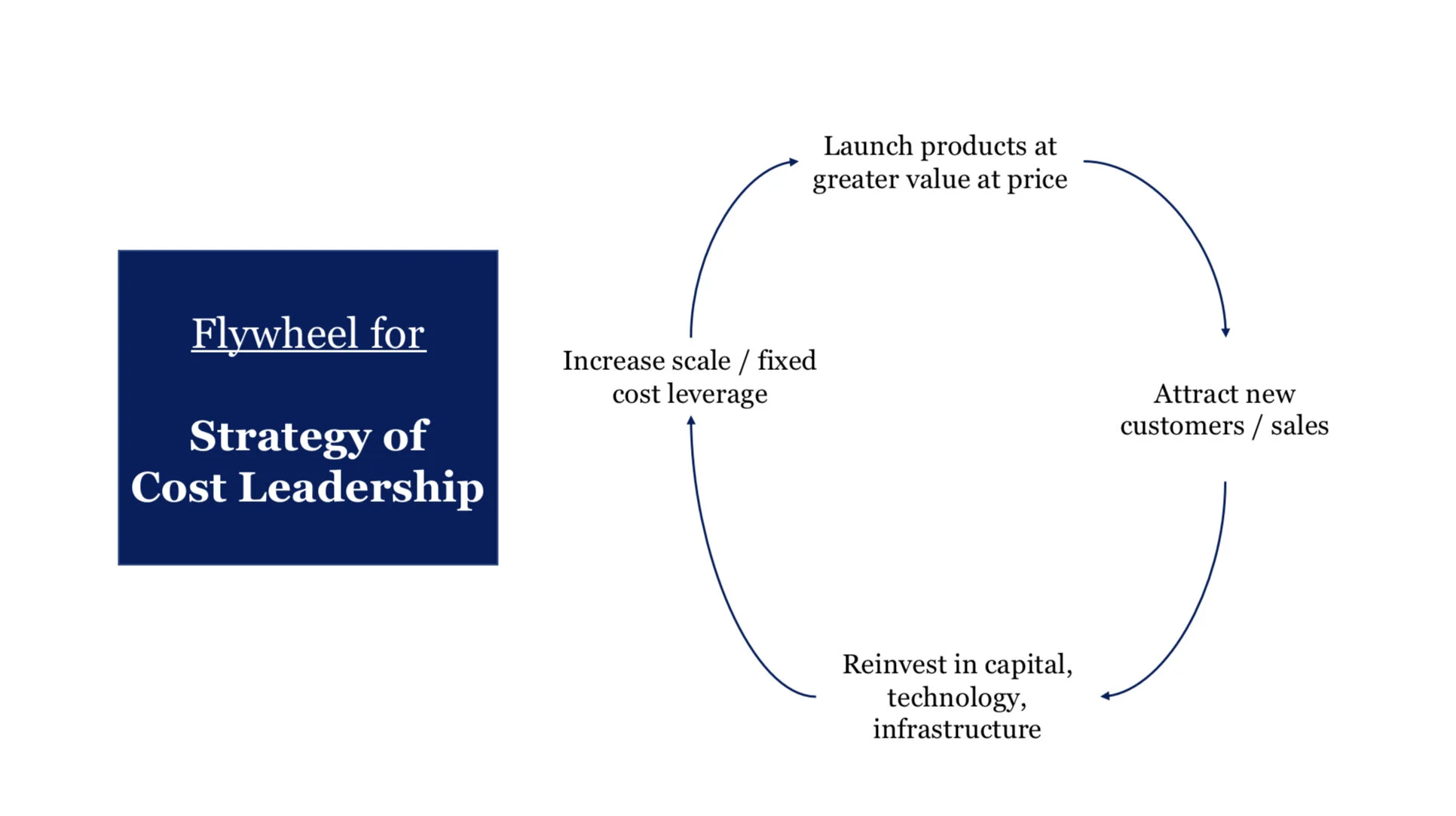

Most business types will be familiar with strategies of differentiation or cost leadership. Both are powerful, value-creating flywheels:

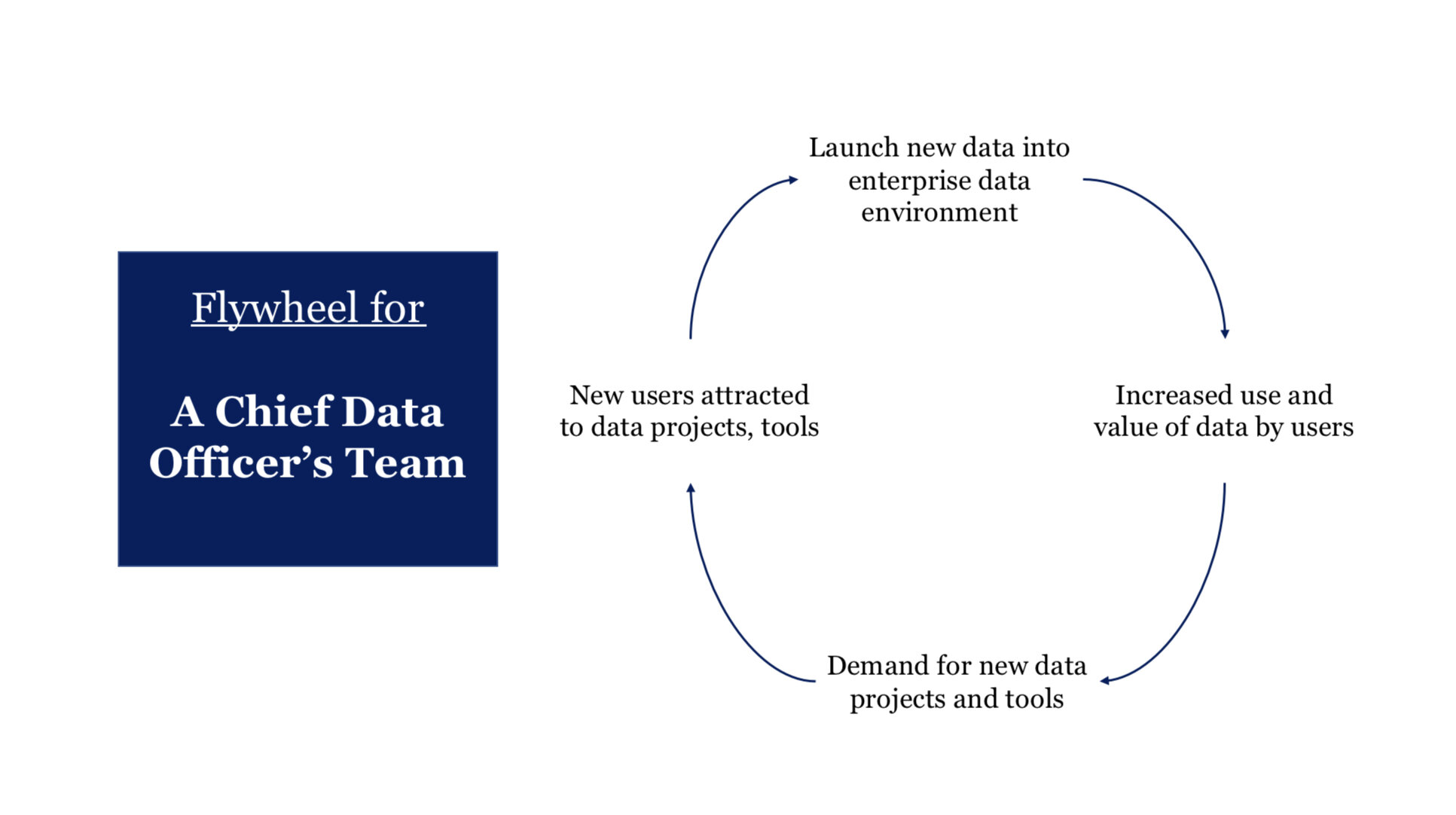

Flywheels are even helpful at the business-unit level. This is an example of how a Chief Data Officer might think about how to create a data-centric culture within their organization.

When experimenting with flywheel thinking, it turns out Robyn and I have been operating a flywheel of sorts within our marriage, and temperature check has been a big part of that.

This is also a good example of how flywheels need to be specific to the stakeholders involved in them. This flywheel doesn’t work for every marriage. Among just our friends, I’ve seen flywheels that are organized around faith or civic engagement.

Gun violence is an interesting example of flywheel thinking because it helps illustrate how particularly complex domains can have multiple flywheels intertwined within them. These are just two dynamics I observed when working on violence prevention initiatives.

Each flywheel has different stakeholders and explain different categories of violence: at the left it’s more about influencing perpetrators making a “business decision” to shoot, at right it’s more about influencing members of trauma-afflicted communities that tend to have simple arguments end with gunfire, usually unintentionally and without pretense.

How we manage and coach is also a classic example of a feedback loop that operates like a flywheel. It’s simplicity doesn’t make it any less powerful, or easy to do in practice.

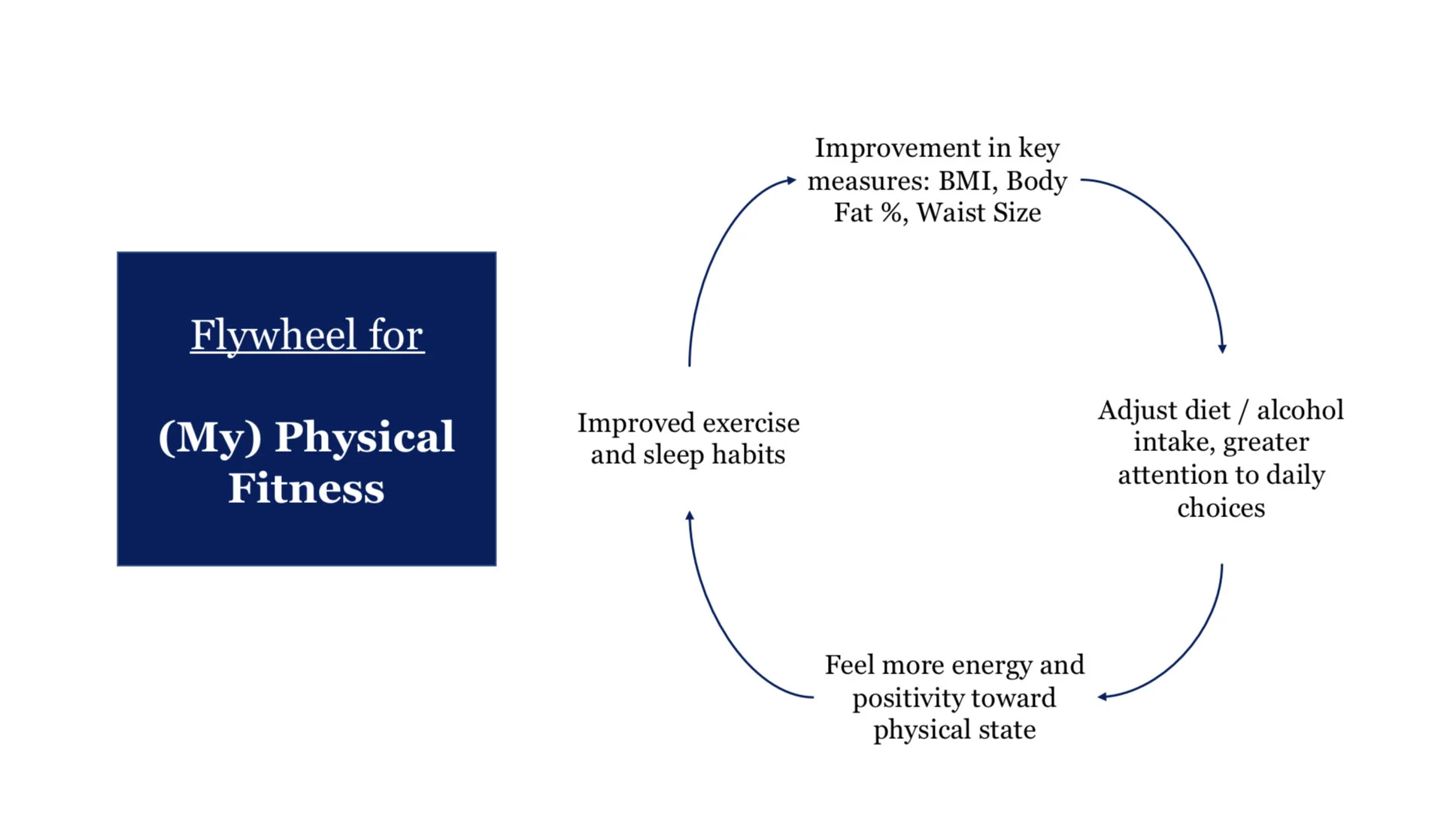

We also have flywheels that explain our behavior as individuals. For me, this is how I specifically respond well to improve my physical fitness.

My flywheel really took off when I understood and started measuring my BMI, Body Fat%, Sleep, Blood Pressure etc. I happen to love the products from Withings because they made the flywheel much more transparent to me as it was occurring, which led to rapid and permanent changes in my behavior.

Social movements utilizing nonviolence techniques (i.e., think US Civil Rights Movement, India Independence) also seem to fit the concept, showing the breadth of flywheel thinking’s explanatory power.

Going through this exercise of identifying flywheels in a number of domains I’m familiar with, I’d offer this practical advice for articulating flywheels in your world:

Think about what is valuable to each involved party. At its core, flywheel thinking is rooted in an understanding of what drives value for everyone. What are the things that if increased or decreased would create win-wins for everyone involved? If the flywheel doesn’t encompass value creation for everyone involved, it’s probably not quite right. Zero-sum flywheels, which create winners and losers between the flywheel’s stakeholders aren’t sustainable because someone will end up trying to sabotage it.

Mind magical thinking. The beauty of the flywheel is that each step in the process is a naturally occurring inevitability of the previous step. Which means as a flywheel detectives we have to be honest about how the world really works; the flywheel has to reflect what the parties involved will actually do in real life and what they’re actually motivated by.

Identify agglomeration. In every flywheel there’s a step where some sort of resource accumulates, and that resource is one where it’s value and impact increases exponentially the more you have of it. That resource could even be things that aren’t technologies or infrastructure (cost leadership example), like data (chief data officer example), knowledge (managing / coaching example), or moral standing (social movement example).

I didn’t use an example with a network effect, but the same idea applies. These agglomerations are all critical resources to the exponential growth unlocked by the flywheel, so if you’re not seeing evidence of that sort of resource agglomeration, the flywheel is probably not quite right.

Identify interactive feedback points. Additionally, there seems to be a step in each flywheel where there is feedback or a learning interaction between the stakeholders participating in the flywheel. Maybe it’s learning about the customer (differentiation strategy example), or maybe it’s response to a measurement (physical fitness example). If there’s not interactive feedback happening, the flywheel is probably not quite right.

I wanted to share this post because applying flywheel thinking is a huge unlock for value creation. It helps, me at least, to get beyond linear thinking and operate at a higher level of effectiveness and purpose.

I get especially excited by how this thinking can apply across disciplines. Jim Collins, who pioneered the concept, is a business guru. But the concept applies broadly, and far beyond what I even suggested - I can imagine it being used to inform feedback loops influencing decarbonization, community development, or regional talent clustering and entrepreneurship.

But flywheel thinking can also be used for nefarious purposes. Rent-seeking and political corruption feedback loops are good examples of this. Specifically, a flywheel like this quickly comes to mind:

My bet is that the sort of people who know me and read my writing are disproportionally good people. By sharing this learning I’ve had, I suppose it’s me trying to do my part create a feedback loop for a community of practice that uses flywheel thinking to make the world a better place.

Reverse Recruiting

Imagine if there were a mechanism like the college common app, except for jobs and hiring.

I imagine how much different life in our country would be if when people went to work, important, valuable, sustainably profitable work is what actually happened. I care about this a lot, because I deeply believe that wasting human potential is inefficient and immoral.

To be able to have these sorts of workplaces, I believe it’s essential to have the right people are in the right roles.

I believe that life is built in the off season. When applying that belief to talent management, it suggests that the best time to recruit is when you don’t need to fill a job in a hurry. Wouldn’t it be so much better - both for companies and candidates - if we already had a pool of interested candidates that were a skill-set and culture fit, before the job were ever posted?

If that intuition is correct, here’s how I think it could actually be put into practice. Imagine if there were a mechanism like the college common app, except for jobs and hiring. I’d love to hear what you think, especially if you’re an HR professional (or have ever been part of a frustrating hiring process).

Here’s how it would work:

First, the candidate takes everything that you would find on a LinkedIn profile and import it into a profile. This could be supplemented with a portfolio of work, confidential letters of referral, or instruments like StrengthsFinder.

Second, the candidate identifies companies they would be interested in working for, were an opportunity available. They’d also identify broadly defined functional areas they were interested in.

Next, the candidate records video answers to a mix of general interview questions - both prepared and extemporaneous. Some questions could be added that are specific to the companies they are interested in working for.

Then the companies take over. They could review and filter the profiles of interested parties and build a pool of candidates for different functional areas. For individuals they think are great fits, they could connect individually or hold invite-only recruitment events a few times a year.

Then, when a job comes up, the process is improved in two ways:

It moves faster for the company and for the candidate, because there are loads of people that are already through what would be covered in a first-round interview

There’s a better fit for both parties because the initial pool of candidates has been built over time, rather than in a hurry when a job is posted. Quantity drives quality.

Again, the whole goal is to have the right people in the right roles, 100% of the time. Do you think this idea actually solves that problem?

—

On September 30, I will stop posting blog updates on Facebook. If you’d like email updates from me once a week with new posts, please leave me your address or pick up the RSS feed.

Imagine if at work...

Imagine if work - that is important, valuable, and sustainably profitable - is actually what happened at work.

Imagine if at work...

...there were no emergencies when you got there in the morning, and were generally rare…

...meetings started and ended on time…

...competition for promotions wasn’t a clobberfest…

...everyone spent nearly 100% of the time on something that was valuable…

...priorities and anti-priorities were clear…

...saying please and thank you were common and sincere…

...when you arrived and left was flexible and predictable…

...interruptions were always important and worth it…

...everyone knew, believed in, and worked the bugs out of the plan…

...the customer’s voice was loud and clear…

...the product was so valuable that margins were comfortable and the customer sold it for you…

...you could always count on everyone to act with integrity…

…and no heroes, all-stars, or herculean efforts were ever needed because we had the right team in place all along.

Imagine if work - that is important, valuable, and sustainably profitable - is actually what happened at work.

For work to actually happen at work, there are three absolute musts: product-market fit, a sustainably profitable business model, and talent-role fit. Strategy is the process to figure out these three things, which makes strategy indispensable too.

Corporate Social Responsibility: maybe nice guys don't exactly finish last?

If companies are competing against each other in the long-term, the company built to last will surely perform better. Just like two different world-class runners: one a sprinter, the other a marathoner, the length of their race will determine who wins.

A few people have posted some really provocative comments. I think I'll hash out some of the ideas presented tomorrow or Saturday.

I had a thought while walking Apollo--my dog--this afternoon; I was ruminating on an blog post I read here: Straight Talk About Corporate Social Responsibility. The piece came from Robert Stavins, a faculty member at Harvard's John F. Kennedy School of Government and was published on the website of the Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs at KSG.

The post offered four questions to ask when thinking about firms and Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) and some analysis about each of the questions: may they, can they, should they, and do they?

The post also asserted that in many (if not most) cases a CSR-friendly firm--the nice guy, so to speak--does not reap substantial benefit from that choice. Moreover, the firms that do benefit from the move are often existing market leaders. (Of course, the preceding summary is rough, read the post for the author's exact idea...don't worry it's short).

Which got me thinking about nice guys. Why does the adage go, "nice guys finish last"? Well, I don't think nice guys always finish last, it just depends on the length of the race. If companies are competing against eachother in the short-term the company built for short-term results will surely win. If companies are competing against eachother in the long-term, the company built to last will surely perform better. Just like two different world-class runners: one a sprinter, the other a marathoner, the length of their race will determine who wins. If they race in a 200m dash, the sprinter will surely win. If they race a longer distance, the marathoner will surely win. Anecdotally, the "nice guy" successfully courts girls interested in building a long-term relationship, but fouls up with women who are looking for the opposite.

Firms that engage in CSR are firms investing in their long-term health, on balance. I don't exactly know if this is true, but let's assume that the majority of said firms are choosing to engage in CSR for longer-term reasons, relative to firms not engaging in CSR as rigorously.

These CSR-friendly firms are the "nice guys" that succeed in long-term initiatives. It doesn't pay to be CSR-friendly unless it's a long-term business strategy...perhaps a move that changes the competitive landscape over time or will dramatically reduce variable costs in 35 years. Maybe the socially responsibile activities require investment in the short to medium term, but pay dividends in the long-term. Maybe CSR is something that changes the culture of the company, but never leaves a direct mark on stock price. In summary, firms conscious of CSR--and I mean ones that do serious stuff, not off-setting carbon footprint as a PR stunt--might not have any benefit doing so in the short-run. CSR-friendly firms are the marathoners, not the sprinters.

This presents a problem for advocates of CSR, whether the advocates are firms, policy-makers or issue publics, if success is measured in the short-term. Which it seems like it is. Quarterly earnings reports, stock-price, etc. are measures that incentivize behaviors which yield short-term gains, right?

CSR-friendly firms are like marathoners trying to beat a sprinter in a 200m dash. Imagine if there were respected measures of corporations' performance that emphasized long-term vitality. Would that change the actions of companies? Would the changes be drastic? Are there measures of long-term vitality used for evaluating companies now?

Nice guys will certainly finish last in races that don't play to their strengths. But if they change the parameters of the race, maybe they'll win. I think this applies to firms and to nice-guys, generally. Rather, I hope so.