Management Is Shifting From Leadership to Authorship

The same forces that disrupted the macroeconomy - like the internet and globalization - are making a similar disruption to the management of firms.

Harnessing this disruption is critical - to ensure the growth individual companies, but also for the continued progress of society at large.

It’s not that management is about to change at a fundamental level. What I’d propose is that it already has changed, but we just haven’t noticed it yet.

I predict that we will start noticing dramatic change in management practices within the next 10 years, because Covid-19 accelerated two trends that have been brewing for the previous quarter century: the digitization of internal firm communications, and, the adoption of Agile management practices.

What’s the fundamental change that’s happened in management?

In a sentence, the way I think about this fundamental change is that management is shifting its primary paradigm from “leadership” to “authorship”.

The paradigm of leadership is that there are leaders and followers. In a world oriented toward leadership, the manager is responsible for delivering results, making the efforts of the team exceed the sum of its parts, and aligning the team’s efforts so they contribute to the goals of the larger enterprise. The leader-manager takes on the role of structuring the vision, process, and the management structures for the team to hit its goals. The leader is directly responsible for their direct reports and accountable for their results. The leader-manager paradigm is effective in environments that call for centralization, control, consistency, and accountability.

The paradigm of authorship is that there are customers and needs to fulfill, that everyone is ultimately responsible for in their own way. In a world oriented toward authorship the manager is responsible for understanding a valuable need, setting a clear and compelling objective, and creating clear lanes for others to contribute. The author-manager takes on the role of finding the right objectives, communicating a simple and compelling story about them, and creating a platform for shared accountability rather than scripting how coordination will occur. The author-manager paradigm is effective in environments that call for dynamism, responsiveness, and multi-disciplinary problem solving.

This distinction really becomes clearer when thinking about the skills and capabilities critical to authorship. To be successful as an author-manager one must be incredibly good at really understanding a customer, and articulating how to serve them in an inspiring and compelling way. The author-manager has to create simple, cohesive narratives and share them. The author-manager needs to build relationships across an entire enterprise (and perhaps outside the firm) to bring skills and talents to a compelling problem, much as a lighting rod attracts lighting. The author-manager needs to create systems and platforms for teams to manage themselves and then step out of the way of progress. This set of capabilities is very different than the core MBA curriculum of strategy, marketing, operations, accounting, statistics, and finance.

In both paradigms, management fundamentals still matter. Both postures of management - leadership and authorship - require great skill, are important, and are difficult to do well. I don’t mean to imply that “leadership” is without value. The relative value of each, however, depends on the context in which they are being used. And for us, here in 2022, the context has definitely shifted.

How has the context related to the internal organizations of firms shifted?

In a sentence, firms are shifting from hierarchies to networks.

I’d note before any further discussion that this is idea of shifting from hierarchies to networks is not a new idea. General Stanley McChrystal saw this shift happening while fighting terrorist networks. Marc Andreessen and other guests on the Farnam Street Knowledge Project podcast also hint at this shift directly or indirectly. So do progressive thinkers on management, like Steven Denning. I’m not the first to the party here, but there’s some context I would add to help explain the shift in a bit more detail.

After the industrial revolution, as economies and global markets began to liberalize in the 20th Century, companies got big. Economies of scale and fixed cost leverage started to matter a lot. Multinationals started popping up. Globalization happened. Lots of forces converged and all these large corporations and institutions came into existence and needed to be managed effectively.

Hierarchical bureaucracies filled this need. In these hierarchical bureaucracies, tiers of leader-managers worked at the behest of a firm’s senior management team, to help them exert their vision and influence on a global scale. The vision and strategy were set at the top, and the layers of managers implemented this vision.

I think of it like water moving through a system of pipes In a hierarchy, it is the job of the executive team to create pressure, urgency, and direction and push that “water” down to the next layer. Then the next layer down added their own pressure and pushed the water down to the next layer, and so on, until the employees on the front line were coordinated and in line with the vision of the executive team. This was the MO in the 20th and early 21st Century.

A network operates quite differently, it functions on objectives, stories, and clearly articulated roles. In a network an author-manager sees a need that a customer or stakeholder has. Then, they figure out how to communicate it as an objective - with a clear purpose, intended outcome, measure for success, and rules of engagement for working together. This exercise is not like that of the hierarchy where the manager exerts pressure downward and aims for compliance to the vision. In a network what matters is putting out a clear and compelling bat signal, and then giving the people who engage the principles and parameters to self-organize and execute.

Both approaches - hierarchies and networks - are effective in the right circumstances. But a trade off surely exists: put briefly, the trade-off between hierarchies and networks is a trade-off between control and dynamism.

Why is this change happening?

In the 20th century, control mattered a lot. These were large, global companies that needed to deliver results. But then, digital infrastructures (i.e., internet and computing) started to make information to flow faster. Economic policies become more liberal so goods and people also started to flow faster. And all these changes led to consumers having more choice, information, and therefore more power. Again, this was not my idea, John Hagel, John Seeley Brown, Lang Davison, and Deloitte’s Center for the Edge articulated “The Big Shift” in a monumental report almost 15 years ago.

Here’s the top-level punchline: the internet showed up, consumers got a lot more power because of it, the global marketplace was disrupted, and firms started to have to be much more responsive to consumers’ needs. The trade-off between control and dynamism tilted toward dynamism.

What I’d suggest is that these same force that affected the global market also affected the inner world of firms. That influence on the firm is what’s tilting the balance from leadership and hierarchy to authorship and networks.

To start, digital infrastructures like the internet didn’t just change information flows in the market, it changed information flows inside the firm. Before, information had to flow through cascades of people and analog communication channels. The leader-manager layer of the organization was the mediator of internal firm communications. In the pre-digital world, there was no other way to transmit information from senior executives to the front-line - the only option was playing telephone, figuratively and literally.

But now, that’s different. Anyone in a company can now communicate with anyone else if they choose to. We don’t even just have email anymore. Thanks to Covid-19, the use of digital communication channels like Zoom, Slack, and MS Teams are widely adopted. We now have internal company social networks and apps that work on any smartphone and actually reach front-line employees. We have easy and cheap ways to make videos and other visualizations of complex messages and share them with anyone, in any language, across the world. Just like eCommerce retailers can circumvent traditional distribution channels and sell directly to consumers, people inside companies can circumvent middle managers and talk directly to the colleagues they most want to engage.

Now, more than ever, putting out a bat signal that attracts people with diverse skills and experience from across a firm to solve a problem actually can happen. Before, there was no other choice but to operate as a hierarchy - middle level managers were needed as go-between because direct communication was not possible or cheap. But now that’s different, any person - whether it’s the CEO or a front-line customer service rep - can use digital communication channels to interact with any other node in the firm’s network if they choose to.

I’ve lived this change personally. When I started as a Human Capital Consultant in 2009, we used to think about communicating through cascaded emails from executives, to directors, to managers, to front-line employees. Now, when I work on communicating strategy and vision across global enterprises, our small but mighty communications team works directly with front-line mangers who run plants and stores. We might actually avoid working through layers of hierarchy because it slow and our message ends up getting diluted anyway. Working through a network is better and faster than depending on a hierarchy to “cascade the message down.”

Agile management practices have also enabled the shift from hierarchies to network occur. Agile was formally introduced shortly after the turn of the 21st century as a set of principles to use in software development and project management. There’s lots of experts on Agile, SCRUM and other related methodologies, but what I find relevant to this discussion is that Agile practices allow teams to work more modularly and therefore more dynamically than typical teams. Working in two week sprints with a clear output scoped out, for example, makes it so that new people can more easily plug in and out of a team’s workflow.

What that means in practice is that the guidance, direction, accountability, and pressure of a hierarchy is no longer necessary to get work done. Teams with clarity on their customer, their intended outcome, and their objectives can manage work themselves without the need for centralized leadership from the focal point of a hierarchy. Agile practices allow networks of people to form, work, and dissolve fluidly around objectives instead of rigid functional responsibilities. Especially when you add in the influence of Peter Drucker’s Management by Objective in the 1950s and the OKR framework developed at Intel in the 1970’s, working in networks is now possible in ways that weren’t even 25 years ago. For the first time, maybe ever, large enterprises don’t absolutely need hierarchical management.

I lived this reality out when our team hosted an intern this summer. I was part of a team which was using Agile principles to manage itself. Our team’s intern was able to integrate into a bi-weekly sprint and start contributing within hours, rather than after days or weeks of orientation. Instead of needing a long ramp up and searching for a role, he just took a few analytical tasks at a sprint review and started running. Even though I’m biased as a true-believer of Agile, I was shocked at how easily he was able to plug in and out of our team over the course of his summer internship, and how quickly he was able to contribute something meaningful.

Even 20 years ago, this modular, networked way of working was much harder because nobody had invented it yet, or at a minimum these practices weren’t widely adopted. Now, these two ideas of Agile and OKR are baked into dozens, maybe hundreds, of software tools used by teams and enterprises all around the world. It’s not that these new, more network-oriented ways of working are going to hit the mainstream, they already have.

The adoption of digital communication tools and Agile practices inside firms has been stewing for a long time. Covid merely accelerated the adoption and the culture change that was already occurring.

And as if that wasn’t enough, the landscape could be entirely different a decade from now if and when blockchain and smart contracts emerge, further blurring the boundaries of the firm and it’s ecosystem. It’s not that management is going to shift, it already has, and it will continue to.

Why does it all matter?

I wrote and thought about this piece because I’ve observed some firms become more successful than their competitors, and I’ve observed some managers become more successful than their peers. I’ve been trying to explain why so I could share my observations with others.

And the simple reason is, some firms and some managers are embracing authorship and networks, while their less successful peers are holding tight to traditional leadership and hierarchy.

Managers who want to be successful act differently. If the world has become more dynamic, managers can’t stick with the same old posture of leadership and clutching the remnants of a hierarchical world. What managers have to do instead is lean into authorship and learn to operate effectively in networked ecosystems.

But I think the stakes are much larger than the career advancement and professional success of managers. What’s more significant to appreciate is the huge mismatch many organizations have between their management paradigm and their operating environment.

The way I see it, enterprises that are stuck in the 20th Century mindset of leadership and hierarchy rather than authorship and networks are missing huge opportunities to create value for their stakeholders. If you’re part of an organization that’s stuck in the past, prepare to be beat by those who’ve embraced authorship, networks, and agility.

But more than that, this mismatch prevents forward progress, not just for individual enterprises, but for our entire society. Management scholar Gary Hamel estimates this bureaucracy tax to be three trillion dollars.

For most people, thinking about management structure is burning and pedantic, but I disagree. Modernizing the practice of management is just as important as upgrading an enterprise’s information technology and doing so successfully leads to a huge windfall gain of value. To progress our society, we have to fix this mismatch so that the management practices deployed widely in the organizational world are the best possible approaches for solving the most critical challenges our teams, companies, NGOs, and governments face. I honestly don’t think it’s hyperbolic to say this: the welfare of future generations depends, in part, on us shifting management from leadership and hierarchy to authorship and networks.

To make faster progress - whether at the level of a team, a firm, or an institution - embracing this fundamental shift in management from leadership and hierarchy to authorship and networks is non-negotiable. Remember, it’s not that this shift is going to happen, it already has.

Photo from Unsplash, by @deepmind

Culture Change is Role Modeling

Lots of topics related to “leadership” are made out to be complicated, but they’re actually simple.

Culture change is an example of this phenomenon, it’s mostly just role modeling.

Probably 80% of “culture change” in organizations is role modeling. Maybe 20% is changing systems and structures. Most organizations I’ve been part of, however, obsess about changing systems instead of role modeling.

In real life, “culture change” basically work like this.

First, someone chooses to behave differently than the status quo, and does it in a way that others can see it. This role modeling is not complicated, it just takes guts.

Two, If the behavior leads to a more desirable outcome, other institutional actors take notice and start to mimic it.

This is one reason why people say “culture starts at the top.” People at the top of hierarchies are much more visible, so when they change their behavior, people tend notice. Culture change doesn’t have to start at the top, but it’s much faster if it does.

Three, if the behavior change is persistent and the institutional actors are adamant, they end up forcing the systems around the behavior to change, and change in a way that reinforces the new behavior. This is another reason why “culture starts at the top”. Senior executives don’t have to ask permission to change systems and structures, then can just force the people who work for them to do it.

If the systems and structure change are achieved, even a little, the new behavior then has less friction and a path dependency is created. A positive feedback loop is born, and before you know it the behvaior is the new norm. See the example in the notes below.

Again, this is not a complicated. Role modeling is a very straightforward concept. It just takes a lot of courage, which is why it doesn’t happen all the time.

A lot of times, I feel like organizations make a big deal about “culture change” and “transformation”. Those efforts end up having all these elaborate frameworks, strategies, roadmaps, and project plans. I’m talking and endless amount of PowerPoint slides. Endless.

I think we can save all that busywork. All we have to do is shine a light on the role models, or be a role model ourselves…ideally it’s the latter. The secret ingredient is no secret - culture change takes courage.

So If we don’t see culture change happening in our organization, we probably don’t need more strategy or more elaborate project plans, we probably just need more guts.

—

Example: one way to create an outcomes / metrics-oriented culture through role modeling.

Head of organization role models and asks a team working on a strategic project to show the data that justifies the most recent decision.

Head of organization extends role modeling by using data to explain justification when explaining decision to customers and stakeholders in a press conference.

Head of organization keeps role modeling - now they ask for a real-time dashboard of the data to monitor success on an ongoing basis.

Other projects see how the data-driven project gets more attention and resources. They build their own dashboards. More executives start demanding data-driven justifications of big decisions.

All this dashboard building forces the organization’s data and intelligence team to have more structured and standardized data.

What started as role modeling becomes a feedback loop: more executives ask for data, which causes more projects to use data and metrics, which makes quality data more available, which leads to more asks for data, and so on.

*Note - this example is not out of my imagination. This is what I saw happening because of the Mayor and the Senior Leadership Team at the City of Detroit during my tenure there.

How We Should Treat Aliens

Thinking about how to treat aliens, helps us think about how we treat each other.

How should I treat a glass of water? Here are a few gut reactions:

I should not shatter it senselessly on the floor. Effort and resources went into making the glass. Destroying it for no reason would be wasteful.

I should keep it clean and in good working order. That way, there’s no stress because it’s ready for use. There’s no need to inconvenience someone else with even a trivial amount of unnecessary suffering.

I should use it in a way that’s helpful. It would be exploitative, in a way, if I took a perfectly good glass and used it as a weapon. If it’s there, I might as well use it to quench thirst, or do something else positive with it. Even glasses are better used for noble purposes than ignoble ones.

If I’m thirsty, I should drink the water. After all, it’s here and it won’t be here for ever - life is short.

And finally, if someone else is thirsty, I should share what I have. After all, we’re all in this together, trying to survive in a lonely universe.

How should I treat an alien?

The thought experiment of the glass of water is interesting because I don’t know how the glass wants to be treated. I can’t communicate with the glass, so I don’t even know if it has preferences. It is after all, just a glass.

And because the glass doesn’t have any discernible preferences, all my suppositions on how to treat the glass are a reflection of my own intuitions about how other beings should be treated. The question is a revealing one, if one chooses to play along with the thought experiment, because I’m asking a question that’s usually reserved for sentient being about an inanimate object. I can more easily access my true, unbiased, preference because I’m thinking about how to treat a glass of water and not, say, my wife and children.

Helpfully, asking the question revealed some of my deep-seeded moral principles. Each of these intuitions are builds on one of the statements I made above:

Don’t be wasteful - energy, and resources are finite.

Be kind - other beings feel pain so it’s good not to inflict suffering unnecessarily.

Have good intentions - I have the chance to make the world better, using my talents for good purposes. The world can be cruel, so why not make it more tolerable for others.

Uncertainty matters - Sooner is better than later because we don’t know how much time we have left. If you have an opportunity, take it. The opportunity cost of time is high, and the future has a risk of not happening the way we want it to.

Cooperate if you can - we are all in this universe together, nobody can help us but each other. Life is precious, beautiful, and so rare in this universe, so we should try to keep it going even if it requires sacrifices.

Like a glass of water, if we were to come across an alien species, we would not know what their preferences were. But unlike a glass of water, the aliens might actually have preferences - presumably, the aliens wouldn’t be inanimate objects.

And let’s assume for a minute that we out to respect the moral preferences of aliens, though I acknowledge that whether or not to recognize the moral standing of aliens is a different question, which we may not answer affirmatively.

But let’s say we did.

How we should treat aliens (and how they might treat us)

What this thought experiment helps to reveal is that we have meta-constraints that shape our moral intuitions and in turn, affect our moral preferences.

It matters to our morality that resources and energy are finite. It matters to our morality that we feel mental and physical pain. It matters that the world is an imperfect, sometimes brutal, place. It matters that the future is uncertain. It matters that life is fragile and that for the entirety of our history we’ve never found it anywhere else. Our reality is shaped by these constraints and manifest in how we think about moral questions.

So, like many difficult questions I only have a probabilistic answer to the question of how we should treat aliens: I think it depends. If they face the same sorts of constraints we do, maybe we should treat them as we treat humans. If they face the same constraints we do - like finite resources, uncertainty, and the feeling of physical pain - maybe we could also expect them to treat us with a strangely familiar morality, that even feels human.

But what if? What if the aliens’ face no resource constraints? What if their life spans are nearly infinite? What if their predictive modeling of the future is nearly perfect? What if they know of life existing infinitely across the universe? If some of these “facts” we believe to be universal, are only earthly, it’s quite possible that the aliens’ moral framework is, pun intended, quite alien to our own.

Maybe we’ll encounter aliens 10,000 years or more from now, and maybe it’ll be next week. Who knows. I hope if you are a human from the far out future, relative to my existence in the 21st Century, I hope you find this primitive thought experiment helpful as you prepare to make first contact. More than anything, I’m trying to offer an approach to even contemplate the question of alien morality: one tack we can take is to look at the meta-constraints that affect us at the species and planetary level, and then see how the aliens’ constraints compare.

But for all us living now, in the year of our lord, two thousand twenty two, I think there’s still a takeaway. Thinking about how we should treat glasses of water and aliens provides a window into our own sense of right and wrong. Maybe we can use these same discerned principles to better understand other cultures and other periods of history. Do other cultures have different levels of scarcity or uncertainty, for example? Maybe that affects their culture’s moral attitudes, and we can use that insight to get along better.

If we’re lucky, doing this sort of comparative moral analysis will make the people and species we share this planet with feel a little less, well, alien, while we figure out who else is out there in the universe.

They Need Me To Lead

I cannot break my sons’ innocence early by asking them to dance with my heaviest emotions.

I believe in the practice of walking the talk, especially as a father. Because even as cliche as it is to say, actions definitely speak louder than words.

I know it, because I act like my father. At the hospital, the day before he died, some of his colleagues came to see us and warmly recounted how passionately my father would present a data analysis and how he’d gesticulate, wildly sometimes, to make his point. I never knew that about him, I thought, but I do that too. And sure as shit, when I see my sons, already, intonate their words up or make up pretend games about spaceships, I know they’re acting like me.

As a general rule, I don’t want to be a morally lethargic parent, allergic to even the smallest personal transformation, that cranks on with tropes like, “do as I say, not as I do”. Like, if I want them to stop picking their noses or stop exhibiting the desperate signs of needing to please authority figures, I have to stop doing that myself, or at a minimum be silent on the issue.

And yet, I’ve found a specific uncomfortable, alien, circumstance where I cannot do what I tell them to do.

What I tell them is something along the lines of:

“Bo and Myles, if you want your brother to stop hitting you, you need to tell them to stop, clearly. And if they don’t listen you need to tell them why. I’m here to help you if you can’t figure it out on your own.”

But if it’s bedtime and Myles is going around in circles to the point of running face first into wall of their shared bedroom, while Bo is jumping on his bed and giggling and screaming about the potty, I cannot do what I told them to do.

I cannot tell them to stop running and yelling because that attention just eggs them on and because this behavior, though irritating, is not expressly unsafe. This part is a practical matter.

But I also cannot tell them why I want them to stop. I cannot tell them that I desperately want to spend 20 minutes with their mother talking about something other than our daily grind or syncing up on parenting tactics. I cannot tell them I am exhausted and they’re keeping me from doing the dishes, and the dishes are keeping me from working, and my work is keeping me from sleeping. I cannot tell them how selfish they are for waking up their baby brother who is sleeping in the nursery across the hall. Even though every ounce of flesh in me wants to offload all this frustration and anger onto them…

I cannot ask them for help either. Maybe there’s some exception here but doing so is dangerous territory. I can ask them for help cleaning up toys off the floor, or handing me an infant diaper when my hands are full. But in the middle of a bedtime circus, it’s different - I cannot ask them to carry my emotional burden.

I’m their father, their papa. They need me to be sturdy. They need me to lead and to lean on. They are the sailboats and I must be their safe harbor. They are the explorers and I must be their map and compass. As the temperature rises, I must be their thermostats, not a thermometer.

To make sense of this world, their not-even-school-aged world, they need me. To reassure them that no bad guys will come to get them and take them away under cover of darkness and dreams, they need me. To be the one who stays steady, instead of retaliating, when they hit or scream or kick or spit or piss in anger, they need me. It won’t be like this forever, but for now, they need me to lead.

I have wondered for a long time about childhood, or what it’s supposed to be I guess. I just don’t remember having one. I did, at some point, exist as a child and in childhood, but what was it like? I can’t recall it, save for photographs and loose threads.

I had my early years and it was full of the acceleration you would expect for a middle-class, suburban, child of scrappy South Asian immigrants. And as I kept racing and pacing, my adolescence passed. So did my father, shortly thereafter. And as he left us behind him, I was growing ahead of my time, once again.

It’s as if the passing of my childhood was something I’ve always grieved, without having the presence of mind to use that word as it was happening.

I cannot shatter the glass ceiling of their innocence so early. I just can’t. Not yet. Not until I have to. I can’t thrust them into my world of struggle and responsibility just yet. I can’t get them to help me with the distortions in my own mind. I just can’t. I want them, so badly, to stay in their not-even-school-aged world a little longer.

I feel so often that parenting is a paradox. It’s excruciating but it’s the best. It’s a never-ending slog but it goes by too quickly. It ages you gray or bald, but also keeps you young. So this, it seems, is just the latest paradox - I need to walk the talk because actions speak louder than words, but not on this one thing…I just can’t on this one thing.

Memories Are Only Shards

Memories decay quickly, instantly. And that makes being present, telling stories, and taking photographs so important. We have to protect the shards we have.

At around 2:30pm, when he emerges from the chamber of his midday nap, Myles is at “peak snuggle”. And this day he chose me. I was outlayed on a sofa, tucked into a corner at it’s “L”.

And then, in one single motion, he scooped on top of me, jigsawing in between my knees and sternum. This was a complete surprise, because this never happens. It’s mommy that invariable gets his peak snuggle, not me.

And I was excited-nervous like some get right before an opening kickoff and maybe even before a first date. I wanted to soak this one in, because in addition to this never happening, I’ve come to accept the difficult truth that our kids won’t be little forever.

We will only get 18 Christmases, Diwalis, and birthdays with each of them at home. We will only get 18 summers with them at home. Eventually, Myles’s sternum and knees will outgrow my own. It’s not just a thought of “oh my gawd, this never happens, I’ve gotta soak this in”, it’s a realization that there will be a time where they’re too big for this to ever happen again. Eventually, Myles, and all our children will outgrow the very idea of peak snuggle.

I know this is all fleeting, and so I was trying to just be there, so still, so as not to perturb Myles into realizing he could move on with his day. I tried to notice everything: the softness of his newly chestnut colored hair, which has lightened as the summer unfolded. I noticed the fuzzy nylon texture of his Michigan football jersey. I tried to cement the feel of his fingers as he tried to read my face like a map, as he reached up above his head, past my chin, and to my cheeks. I embraced the particular top-heavy way his two-and-a-half year old frame carried its weight at this specific moment of his life.

But hard as I tried, my efforts to remember were an exercise in grasping at straws. Memories have the shortest of all half lives.

Even 5 minutes later, as I desperately tried to encode my neurons with this moment, I couldn’t quite remember it as it actually happened. Even after just five minutes, I had only the fragments and feelings of something that now was fuzzy and choppy and bits and pieces. What remained was more like a dream than a memory.

All my memories, are this way. I’ve even experimented to test my mind’s resilience to remember, and everything still fades. Even for the most exhilarating moments of my life - like our marriage vows, the birth of our children, or my first time walking into Michigan Stadium - only the fragments remain. It’s excruciating but true that the only time the we ever experience reality is in the very moment we are in, and only if we’re fully there. After just seconds, the memory decays irreparably. All we are left with is a shard of what really happened.

This unfairly short half life of memory has softened my judgement about social media. After stripping away all the vanity, status signalining, and humble bragging, I think there is at least a sliver of desperation and humanity that’s left. At the end of the day, we just all want to remember. And because our minds are too feeble to remember unassisted, we take a photo and share it as a story.

In the past few weeks, as I’ve realized that I don’t truly have any clear, vivid, life-like memories. I’ve almost panicked about what to do. This is why we have to tell stories. Stories, just like photographs are a way to save a little shard of something beautiful. This is why I have to get sleep. The sleep keeps my eyes wide open and puts a leash on my mind so it doesn’t recklessly wander away from reality as it’s happening. And, most importantly, this is why I have to be with them.

We treasure our relationships and are so protective of them for a reason. If we find friends, family, or colleagues that we actually want to remember, we know intuitively that we ought to see them as much as we can. We know intuitively that if we see those treasured people often, maybe it’ll slow down the decay of our memories a little. Life is too short to throw away chances to be with the people we want, so desperately, to remember. This is why I have to be with them.

And just like that, Myles moved on with his day. He scooped off the sofa, just as quickly as he arrived. Peak snuggle was over. And my memory started to decay immediately, as I expected. But at least I do have this fragment of a feeling. And, thank God that even if I won’t be able to ever have full, real memories of this beautiful moment, I will at least have the shards of it.

“I Promise”

As your father, I promise to love you unconditionally and help you become good people.

Succeeding in pursuit of a goal, I’ve learned, can be simple as long as you ask yourself the right questions. Graduate school - and everything I've read about management that's any good - taught me that the first question to ask yourself before starting any journey is "what result do I want to create?"[1] The idea is, once you clarify exactly what success looks like (and what it doesn't) you can spend all your time working at that result, instead of wasting time and effort toward anything else.

As a father, what result do I want to create? I've thought about that a lot as Robert’s birth approached and since then, as all of you have come into the world. The result I want to create is simple: I want you all to feel loved and become good people. Therefore, my duty as a father, as I see it, is two fold: 1) love you unconditionally, and, 2) help you become good people.

That's it. That’s the mission – to love you unconditionally and help you three become good people. Anything else that comes of my influence in your life is a bonus.

Let me be perfectly up front with you, too – my mission is not your happiness. Obviously, I hope you all live healthy, happy, and prosperous lives. But I'm not committing to or focusing on that. Goodness and happiness are not the same thing and I am focused on goodness, not happiness.

For one, each of you three are the only people who can make you healthy, happy, and prosperous. Guaranteeing your health, happiness, and prosperity is a promise I can’t keep. It’s difficult for me to admit that, but it’s true; health, happiness, and prosperity are only in your hands or the hands of God.

I can’t even truly promise that I will succeed in helping each of you to become good people. I am a mortal, imperfect, man just like you are, who is frustratingly fallible – and so are you. Only a God could veritably guarantee that they could help you become a good person, and a God is something I certainly am not. I may fail at my mission, even if I die trying.

But here’s what I do promise, right now, in writing. Our word is our bond, and these are quite literally my words. I promise two things, to you three, my sons.

First, I promise you that I will never give up on cultivating the goodness in you or in myself.

I will work to do that as long as I exist in body, mind, or spirit. How I approach that task will change as you grow older, but I will never give up on it. I will make mistakes, and I will learn from them. I am committed to the challenge because it is the most important thing I will ever do. I am in it for the long haul.

One of the books I will read to you one day is East of Eden[2] by John Steinbeck. It is one of my favorites and the most important novel I have ever read. I first read it in high school and I don't even remember most of the plot. What I do remember is what I consider to be it’s most important idea - timshel.

Lee, one of the characters in the book, tells the story of a Biblical passage discussing man's conquering of sin – “the sixteen verses of the fourth chapter of Genesis”. Something interesting that Lee finds is that different translations of the Bible have different understanding of what God says about man’s ability to conquer sin.

One translation – from the King James version – says that thou shall conquer sin, implying that a man overcoming his sinning ways is an inevitability. Man shall conquer sin, it’s a done deal. The other translation – the American Standard version – says “do thou”, that thou must conquer sin, implying that God commands man to overcome his sin. In this version it’s not an inevitability, it’s an imperative.

These two translations are obviously radically different, which leaves Lee flummoxed. What he does to remedy this confusion is go back to the original Hebrew (with the help of a few sage old men), to see the exact words used in the original scripture. His hope is that by going back to the original Hebrew, he will be able to decipher a more accurate understanding of the verse’s intent.

In the original Hebrew, Lee finds the word timshel in the verse. This “timshel” word, Steinbeck reveals, translates to “thou mayest” conquer sin. So, conquering our sins is not an inevitability and it's not an imperative - it's a choice. A choice! It is up to us whether we conquer our sins and become good men. What Steinbeck conveys is that the Biblical God says timshel - that we may conquer our sins, if that is the choice we make.

That’s what I have chosen. I choose to try, to try to conquer sin. I choose to try to be a better man, and to try to help you three, my three sons, to become better men, too. I will never give up on you, boys, I swear to you that.

What Steinbeck reminds us, is that conquering our sin is in our hands. Becoming good is our choice. And my first promise to you – my three sons - is to never give up on goodness, and never give up on you, even though I may fail.

But no matter what happens from here forward, this is my second promise to you, no matter what happens. No matter how good or wicked each of you are. No matter how tall or short you are. No matter how wealthy or poor you become, no matter what you look or act like, no matter what - I will always love you, unconditionally, and so will your mother. Always. Always. Always.

I promise.

—

[1] From Lift: Becoming a Positive Force in Any Situation, Ryan W. Quinn and Robert E. Quinn

[2] From East of Eden, John Steinbeck

This passage is from a book I’ve drafted and am currently editing. To learn more and sign up to receive updates / excerpts click here.

Our stories are about light

My dream about light is making it, sharing it, and all of us finding a way home.

In his 2019 memoir, A Dream About Lightning Bugs, musician Ben Folds reveals the meaning of the title a few pages into the manuscript. It was a dream he had as a kid, where he would be in the thick of summer and with awe be catching lightning bugs in a jar.

But for Folds, catching lightning bugs is more than just a whimsical childhood dream, it became a metaphor for the meaning of his life. In the first few chapters, Folds explains that he sees his purpose to catch lighting bugs, through his music, and share that momentary wondrous glow with others. That’s what he’s here for, to catch and share the light.

I heard this story about 15 minutes into a run, while listening to an audiobook of Folds’ memoir.

Damn, I thought while trodding up Livernois Avenue, metaphors about light are so powerful and universal. Why is that?

When really zooming out, what are our lives, really, other than a sequence of concentrating energy, reapplying it somehow, and embracing its dissolution? And what is light, but a transcendent and beautiful form of energy? So much of how we understand our own existence, too, can be thought of as a relationship between light and it’s absence. In a way, all our stories, our most important ones anyway, can be understood as a relationship with light.

As I kept running, Folds in my ear, I continued to think. Folds’ deal is lightning bugs, but why am I here?

I’m not here to be a lighthouse, I need to be with people in the trenches, not guiding from a distance. I’m not here to be a telescope, pondering into the heavens trying to decipher the secrets of the faintest sources of light. I’m not here to be commanding the spotlight to bring voice to the voiceless. I’m not here to be a firework, illuminating celebrations with color and magic.

Why am I here? What’s my dream about light?

We find ourselves often, in a dark, wet, cave. As Socrates might argue, perhaps that’s the state we are born into. If that’s true, I think I am here to make a fire, creating a light. I’m here to transfer that light onto a torch and find the others in the cave. I am here to take my torch and light the torches of others, give light away as fast as I obtain it. I am here to leave lanterns at waypoints as we go, making the once dark cave, brighter. And maybe I won’t survive long enough to find the way out of the cave. That’s okay.

My dream is not one about lightning bugs. My dream is one of making light, and sharing it with others so we can all go home someday.

I think this is a belief I’ve held for a long time, without consciously realizing it. Perhaps that’s why I’ve been writing this blog for almost 20 years, for no money, and resisting click-bait topics to gain an audience - even though sometimes I feel like I’m singing into a dark, empty cave. I can’t help but share the little bit of light I think I’m discovering with others. It’s what I’m here to do.

It’s so audacious, I think, to engage in this enterprise of “purpose”. Figuring out why we’re here? Trying to understand what our life is supposed to mean? It’s heavy, big stuff. I don’t really have it figured out, and I think anyone who claims they have a magic formula to figure it out is probably lying.

But this exercise, forcing myself to examine my life and turn it into a dream about light was useful. It worked. I don’t have all the answers, but I do feel clearer, about what my life is not, at least. If you’re similarly foolish and trying to figure out why you’re here, it’s an exercise I’d recommend to you, no matter who you are or what your backstory is.

Because, at the end of the day, all our stories are about light.

This Is Soul Searching

What has given me organizing principles for living is thinking honestly about what I would be contemplating in the waning moments of my own life.

In the waning moments of my life, what do I want to be true? If I do not die suddenly, and unexpectedly like my father and my others did, I know I will be taking stock of my life. What story do I want to be the real, true, story I am able to tell myself about my own life?

I want it to be true that I did not bring death, senselessly, upon myself. Whatever is left of me after death would be ashamed at my negligence if I was texting while driving, or accidentally injured myself because I was drunk. Similarly, if I died needlessly young because of poor nutrition, air & water quality, rest, stress, or apathy toward my own health, my lingering soul would be devastatingly sad. When my time comes, it will be my time, but I don’t want that time to be recklessly early. Our bones may break, but I do not want to break my own.

I want it to be true that I did right by my family, by other people, and by other living creatures. I would be so regretful if I had lived my life neglecting my family, by being untrustworthy to my friends, disrespectful to my neighbors, unkind to strangers, and insulting to life, as it came to my doorstep, in any form. How could I steal the opportunity for a good day from others? How could I take out anger on children, a dog, or other defenseless creatures? How could I pollute the water or air and bring suffering to living creatures 100 years from now? I cannot selectively value life - I’m either in, or I’m out. And I’m either honest, kind, and respectful of life or I’m not. I either did right by others, or I didn’t. Do or do not, there is no try.

I want it to be true that I used my gifts to make an impactful contribution. I think I have realized that it’s less important to do something “big” or “noteworthy”. What is it that I and few others on this earth could contribute? It takes a village to leave the village better than we found it. What’s my niche? What’s my lane? What’s the diversity of contribution I can bring to the table? Papa always told you that you were a capable person, Honor your gifts, Tambe.

I also want to be at peace with death itself. Some people call this being ready to die, or having come to terms with death. I think that means forgiving and asking for forgiveness. I think that means righting my wrong and accepting the wrongs I could not make right. I think that means having lived a life seeking out, learning from, and hopefully understanding something of the the natural beauty of this world and traveling graciously to experience the beauty of human culture. I think that means having my affairs in order medically, legally, and financially. I think that means having done the hard, spiritual work to be prepared for the unknown and undiscovered country. I think that means knowing that I’ve shared the good parts of life with the good people God has brought me to. I want to be ready. Live like there are 10,000 tomorrows, all of which that may never come.

Thinking through this has been a bit of a reckoning. Am I really living to these principles? I’m not 100% sure.

Do I really, truly, not drive distractedly? Is eating fish consistent with my perspective on respecting life in all its forms? Is working in business, or even public service, really the way to contribute my unique gifts? Have I righted the wrongs of my adolescence and been present for my extended, global family? I’m not quite sure about any of these. I think the exercise of reconciling life today with the person we are at death’s doorstep is what is meant by “soul searching.” And that’s what this is, soul searching.

—-

I have dedicated a significant amount of my life to understanding teams, organizations, and how they work. Understanding these sorts of human systems is one of my unique gifts. And one of the enduring truths of my study is that the way for a human to solve problems is to begin with the end in mind.

What this approach absolutely depends on is knowing what the end actually is. What is our endgame? What are we trying to achieve? What result are we trying to create? We must know this to solve a problem, especially in a team of people.

This post was inspired by a few things - a few conversations with a few members of my extended family at dinner this weekend, and finishing the book The Path to Enlightenment by His Holiness, the Dalai Lama - and it’s become a set of organizing principles of how I want to live. These four ideas: avoiding senseless death, doing right by others, contributing my unique gifts, and find peace with death itself, have been loose threads that I have been trying to weave into a narrative since the beginning of my time writing this blog in earnest, almost 15 years ago.

What I have been missing this whole time is that tricky question - what is the end? What we experience about death in our culture is truly limited. The end of life is not a funeral or a eulogy. The end of life is not what is written about us in a book or newspaper. The end of life is not our retirement party from a job or a milestone birthday in our late ages where everyone makes a speech and says nice things about us.

Those moments are not the end, but those moments are usually what we experience, either in movies, television, or our own lives. The end we have in mind when we tacitly plan out our lives is maximizing those moments. But that’s not the actual end.

At the end of life we are really mostly alone, mostly with our own thoughts. I have never seen dying up close, and I think most people don’t. I did not have grandparents who lived in this hemisphere. My father wen’t ahead so surprisingly. My surviving parents (Robyn’s folks and my mother), thank God, are not quite that old just yet. I have never truly seen the true end of life.

I think for most of my life I have been optimizing for the wrong “end”. I have been trying to design my life around having a great retirement party, or a great funeral. And that has made me put a skewed amount of emphasis on what others might think and say about me one day.

What is the better, and more honest approach is to organize life around the true end: death.

It is hard, but has been liberating. Imagining what I want to believe to be true has given me remarkable clarity on how I want to live. And that is such a gift because, thank goodness, I still have time to make adjustments. It’s not too late. And in a way, I truly believe it’s never too late, because we’re not dead yet. Even if death is only days away, or even hours perhaps, it ain’t over ‘till it’s over. We still have time to choose differently.

If true, am I really a “leader”?

If I choose to shirk responsibility, what am I?

If I choose to…

…say “just give it to me” instead of teach,

…set a low standard so I don’t have to teach,

…blame them for not “being better”,

…blame them for my anger instead of owning it,

…let the outcome we’re trying to achieve remain unclear,

…keep the important reason for what we’re doing a secret,

…leave my own behavior unmeasured and unmanaged,

…set a high standard without being willing to teach,

…proceed without listening to what’s really going on,

…proceed without understanding their superpowers and motivations,

…withhold my true feelings about a problem,

…avoid difficult conversations,

…believe doing gopher work to help the team is “beneath me”,

…steal loyalty by threatening shame or embarrassment,

…move around 1 on 1 time when I get better plans,

…be absent in a time of need (or a time of quiet celebration),

…waffle on a decision,

…or let a known problem fester,

Am I really a “manager” or a “leader”? Can I really call myself a “parent”?

If I’ve shirked all the parts requiring responsibility, what am I?

To me all “leadership” really is, is taking responsibility. It’s the necessary and sufficient condition of it. The listed items I’ve prepared are just some examples of the responsibilities we can choose (or not) to take.

And, definitely, there are about 5 of those that I fail at, regularly. My hope is that by making these moments transparent, it will be more possible to make different choices.

The Great Choice

The greatest of all choices is choosing whether or not to be a good person.

In the spring of 2012, my life was a mess - even though it didn't appear that way to almost everyone, even me. But a few people did realize I was struggling, and that literally changed the trajectory of my life. It was just a little act, noticing, that mattered. And from noticing, care. Those seemingly small acts were a nudge, I suppose, that put me back on the long path I was walking down, before I was able to drift indefinitely in the direction of a man I didn’t want to become.

Those small acts of noticing and care were acts of gracious love, that probably prevented me from squandering years of my life. Without a nudge, it might have been years before I had realized that I lost myself. Because in the spring of 2012, I was making the worst kind of bad choices – the ones I didn’t even know were bad.

But I’m getting ahead of myself here.

Trying to become a good person is like taking a long walk in the woods. It’s winding. It’s strenuous. It’s not always well marked and there are a lot of diversions. There’s also, as it turns out, not a clear destination. Being a good person is not really a place at which we arrive, and then just declare we’re a good person. It’s just a long walk in the woods that we just keep doing – one foot in front of the other.

It is not something we do because it is fun. A long walk in the woods can be chilly, rainy, uncomfortable – not every day is sunny.

Righteousness is a word that I learned at an oddly young age. I must have been 10 or younger, I think. It was a world I heard lots of Indian Aunty’s and Uncles say during Swadhyaya, which is Sanskrit for “self-study” and what my Sunday school for Indian kids was called that I went to as a boy. And when those Auntys and Uncles would teach us prayers and commandments and the like – righteousness was a word that was often translated.

My father also used that word, righteous. I can hear him, still, with his particular pronunciation of the word talking to me about the rite-chus path. This idea of taking a long walk in the woods, you see boys, is an old idea in our culture. To me, talking about being a good person, going on a long walk in the woods, taking the righteous path – whatever you want to call it – are not just words and metaphors. It’s a dharma – a spiritual duty. It’s a long walk down an often difficult, but righteous, path.

But it is still a choice. Will we take the long walk?

This is a choice to you, like it was to me, my father before me, and his father before he. All of your aunts and uncles, grandparents, had this choice. In our family, this is a choice we have had to make – will we walk the righteous path or not? Will we do the right thing, or not? Will we take the long walk, day after day, or will we not? Will we try to be good people, or will we not?

This is the great choice of our lives. We have to choose.

This passage is from a book I’ve drafted and am currently editing. To learn more and sign up to receive updates / excerpts click here.

We Need To Understand Our Superpowers

We need to take the time to understand our superpowers, as individuals or as an organization, so we have the best chance to create surplus.

Surplus is created when something is more valuable than it costs in resources. Creating surplus is one of the keys to peace and prosperity.

Surplus ultimately comes from asymmetry. Asymmetry, briefly put, is when we have something in a disproportionately valuable quantity, relative to the average. This assymetry gives us leverage to make a disproportionally impactful contribution, and that creates surplus.

Let’s take the example of a baker, though this framework could apply to public service or family life. Some asymmetries, unfortunately, have a darker side.

Asymmetry of…

…capability is having the knowledge or skills to do something that others can’t (e.g., making sourdough bread vs. regular wheat).

…information gives the ability to make better decisions than others (e.g., knowing who sells the highest quality wheat at the best price).

…trust is having the integrity and reputation that creates loyalty and collaboration (e.g., 30 years of consistency prevents a customer from trying the latest fad from a competitor).

…leadership is the ability to build a team and utilize talent in a way that creates something larger than it’s parts (e.g., building a team that creates the best cafe in town).

…relationships create opportunities that others cannot replicate (e.g., my best customers introduce me to their brother who want to carry my bread in their network of 100 grocery stores).

…empathy is having the deep understanding of customers and their problems, which lead to innovations (e.g., slicing bread instead of selling it whole).

…capital is having the assets to scale that others can’t match (e.g., I have the money to buy machines which let me grind wheat into flour, reducing costs and increasing freshness).

…power is the ability to bend the rules in my favor (e.g., I get the city council to ban imports of bread into our town).

…status is having the cultural cachet to gain incremental influence without having to create any additional value (e.g., I’m a man so people might take me more seriously).

We need to understand our superpowers

So one of the most valuable things we can do in organizational life is knowing the superpowers which give us assymetry and doing something special with them. We need to take the time to understand our superpowers, as individuals or as an organization, so we have the best chance to create surplus.

And once we have surplus - whether in the form of time, energy, trust, profit, or other resources - we can do something with it. We can turn it into leisure or we can reinvest it in ourselves, our families, our communities, and our planet.

—

Addendum for the management / strategy nerds out there: To put a finer point on this, we also need to understand how asymmetries are changing. For example, capital is easier to access (or less critical) than it was before. For example, I don’t know how to write HTML nor do I have any specialized servers that help me run this website. Squarespace does that for me for a small fee every month. So access to capital assets and capabilities is less asymmetric than 25 years ago, at least in the domain of web publishing.

As the world changes, so does the landscape of asymmetries, which is why we often have to reinvent ourselves.

There’s a great podcast episode on The Knowledge Project where the guest, Kunal Shah, has a brief interlude on information asymmetry. Was definitely an inspiration for this post.

Source: Miguel Bruna on Unsplash

“Friends of friends are all friends”

Being part of a collective story is a very special type of human experience that brings a deep, grounded, and peace-giving joy.

“Friends of friends are all friends”

This is one of the enduring bits of wisdom my friend Wyman has taught me. And sure enough, at the friends’ night the evening before his wedding, we were, indeed, all friends.

This has been the case at the weddings and bachelor parties I’ve been to over the years. I get along swimmingly, without fail, with the friends of my closest friends. And the most fun I’ve had at weddings are usually preluded by an energizing, seemingly providential, friends night. This has been a pattern, not a coincidence.

I think the underlying cause of this is stories, and how we want to be part of stories that matter.

Weddings are great examples of stories that matter. Robyn and I still talk often about stories from our own wedding.

Like the bobbing poster sized cutouts of our heads that our friends Nick and Liz found and the heat it brought to an already sizzling dance floor. We remember the quick stop we had at Atwater brewery for post-ceremony photos, that our entire family showed up at, and the pints of Whango we had to chug on our way to our wedding reception. And I’ve learned to laugh about how my very best friends let me get locked in the church after our wedding rehearsal.

But just as often, we reminisce over the stories of other weddings we’ve attended, where we were just part of the supporting cast, rather than the protagonists.

We remember how we scurried across Northern California to attend a Bay Area and Tahoe wedding in the same weekend. We remember the picnic in a Greenville park and how we climbed a literal mountain for the marriage of Robyn’s closest childhood friend. We relive trips to places like Grand Rapids, Chicago, and Milwaukee and the adventures we’ve had with old friends we reconnected with at destinations across the country.

Weddings are more than just significant, however. They are also collective stories, where the narrative is made from the interwoven threads of an ensemble cast, rather than a single strand dominated by the actions of one person. The bride and groom may be the protagonists, but for a wedding the rest of the ensemble and the setting is just as important. That everyone can be part of the story is exactly the point.

All the best stories, I think, are collective, ensemble tales. The story of a wedding. The novel East of Eden. The story of my family. The story of America. The stories of scripture. The story of a championship athletic teams. The stories of social movements to expand rights and freedoms all across the world. The story of Marvel’s Avengers. The story of great American cities like Detroit, New York, and Chicago. The story of a marriage. The story of our marriage.

These stories are all made up of interwoven threads and an ensemble cast, and that’s what make them transcendent. Collective stories have archetypes and themes that everyone understands, and that’s what makes them powerful and magnetic.

I think the deep yearning to become part of a meaningful, transcendent, collective story is why friends of friends become friends at weddings. The yearning opens our hearts and minds to new experiences and brings out the truest and purest versions of ourselves.

But more broadly than that, collective stories also explain why we see people making seemingly irrational and painful sacrifices for something larger than themselves. The desire to be part of a collective story drives people to do everything from serve their country, commit to a faith, travel thousands of miles to be home for the holidays, or take on a cause that others think is lost.

Being part of a collective story is a very special type of human experience that brings a deep, grounded, and peace-giving joy. Giving someone the chance to be a part of a story like that is one of the greatest gifts that can be given.

“Papa? Will you never die?”

What I need, desperately, is to be here.

“Papa? If you take good care of your body, will you never die?”

This was the last tension, that once revealed, unwound the bedtime tantrums a few nights ago. As it turns out, it wasn’t the imminent end of our annual extended family vacation in northern Michigan that had Bo’s feelings and stomach in knots.

It was death.

Unasked and unanswered questions about death. Doubts about death. Anxiety about death, so insidious that I have not a single clue how the questions were seeded in his mind and why they sprouted so soon.

“I want to be with you for a hundred million infinity years, Papa. A hundred million INFINITY.”

Such earnest, piercing, and deeply empathetic honesty is the fingerprint of our eldest son’s soul.

When he tells me this, my excuses all evaporate. How could I ever not eat right from this day forward? How could I ever get to drunkenness ever again? How can I not be disciplined about, exercise, sleep, and going to the doctor? How could I ever contemplate texting and driving, ever again? How could I let myself stress about something as artificial as a career? For Bo, for Robyn, and our two younger sons, how could I do anything else?

I needed to hear this, this week, because I have been losing focus on what really matters.

I have been moping about how I feel like many of my dreams are fading. My need to return to public service. My need to challenge the power structures that tax my talent everyday at work. The book I need to finish, or the businesses I need to start. Ego stuff.

In my head, at his bedside, my better angels turned the tide in the ongoing battle with my ambition. Those are not needs. Those are wants. To believe they are needs is a delusion. Dreams are important, yes, but they are wants, not needs.

All I really need, desperately, is to be here. To show up. To wake up with sound-enough mind and body. To not lose anyone before the next sunset. To have who and what I am intertwined with to stay intertwined. This is what I need.

What I vowed to Bo is that I would take care of my body, because I wanted to be here for a long, long, long, long, long, long time.

“I will be here for as long as I can. I want to be here, with you and our family, for as long as I can.”

And as he drifted to sleep, I stayed a moment, kneeling, and thought - loudly enough, only, perhaps, for his soul to overhear,

“Please, God, help us all be here for as long as we can.”

Measuring the American Dream

If you set the top 15 metrics, that the country committed to for several decades, what would they be?

In America, during elections, we talk a lot about policies. Which candidate is for this or against that, and so on.

But policies are not a vision for a country. Policies are tools for achieving the dream, not the American Dream itself. Policies are means, not ends.

I’m desperate for political leaders at every level - neighborhood, city, county, state, country, planet - to articulate a vision, a vivid description of the sort of community they want to create, rather than merely describing a set of policies during elections.

This is hard. I know because I’ve tried. Even at the neighborhood level, the level where I engage in politics, it’s hard to articulate a vision for what we want the neighborhood to look like, feel like, and be like 10-15 years from now.

Ideally, political leaders could describe this vision and what a typical day in the community would be like in excruciating detail, like a great novelist sets the scene at the beginning of a book to make the reader feel like they’ve transported into the text.

What are you envisioning an average Monday to be like in 2053? I need to feel it in my bones.

Admittedly, this is really hard. So what’s an alternative?

Metrics.

I’m a big fan of metrics to help run enterprises, because choosing what to measure makes teams get specific about their dreams and what they’re willing to sacrifice.

Imagine if the Congress and the White House came up with a non-partisan set of metrics that we were going to set targets for and measure progress against for decades at a time? That would provide the beginnings of a common vision across party, geography, and agency that everyone could focus on relentlessly.

This is the sort of government management I want, so I took a shot at it. If I was a player in setting the vision for the country, this would be a pretty close set of my top 15 metrics to measure and commit to making progress on as a country.

This was a challenging exercise, here are a few interesting learnings:

It’s hard to pick just 15. But it creates a lot of clarity. Setting a limit forces real talk and hard choices.

It pays to to be clever. If you go to narrow, you don’t have spillover effects. It’s more impactful to pick metrics that if solved, would have lots of other externalities and problems that would be solved along the way. For example, if we committed to reducing gun deaths, we’d necessarily have to make an impact in other areas, such as: community relationships, trust with law enforcement, healthcare costs, and access to mental health services.

You have to think about everybody. Making tough choices on metrics for everyone, makes the architect think about our common issues, needs, and dreams. It’s an exercise that can’t be finished unless it’s inclusive.

You have to think BIG. Metrics that are too narrow, are more easily hijacked by special interests. Metrics that are big, hairy, and audacious make it more difficult to politicize the metric and the target.

Setting up a scorecard, with current state measures and future targets would be a transformative exercise to do at any level of government: from neighborhood to state to nation to planet.

It’s not so important whether my metrics are “right” or if yours are, per se. What matters is we co-create the metrics and are committed to them.

Let’s do it.

“How do I become a good father?”

The question of how to raise good children starts with figuring out how to be a good person myself.

Let me be honest with you.

I don't know whether I'm a good man, whether I will be a good father, or even whether I'll ever have the capacity to know - in the moment, at least - whether I'm either of those things. I, nor anyone, will truly be able to judge whether I was a good father or a good man until decades after I pass on from this earth.

I do know, however, that is what I want and intend to be. I want to be a good father and the father you all need me to be.

Wanting to be a good father was my central objective in writing this book. The sentiment I had in the Spring of 2017, a few months before Bo was born, is the same sentiment I feel now – I want to be a good father, but I need to figure it out. I am not nervous to be a father, but I’m not sure I know how just yet. I am excited to be a father, but what would it mean to be a good one? What do I need to do? How do I actually do it? How do I actually walk the walk?

This book is my answer to this simple, fundamental, difficult question: how do I become a good father? In this letter and the letters that follow, my goal is to answer that question in the greatest rigor and with the most thoughtfulness I can. As you’ll see in the pages that follow, the answer to the question quickly becomes an inquiry on how I become a good person myself, because I need to walk the walk if I want you three to grow to become good people. As it turns out, the best way (and perhaps only way) I could adequately answer this question with the intensity and emotional labor it required was by talking with you all – my three sons – and writing to you directly. You boys are the intended audience of this volume of letters.

When I first started writing in 2017, your mother and I only knew of Robert’s pending birth, though we dreamed of you both, Myles, and Emmett. And by the grace of God, all three of you are here now as I begin rewrites of this manuscript in the spring of 2022, about three weeks after Emmett was born. Now that you three are here, I have edited this volume to address you all in these letters collectively, even though that wasn’t the case in my original draft.

At the beginning of this project, I wasn’t sure if I would share it with anyone but our family. But as I went, I started to believe that the ideas were relevant and worth sharing beyond our roof. This book become something I’ve always wanted from philosophers, but I felt was always missing. As comprehensive as moral philosophy and theology are with the question of “what” – what is good, what is the right choice, etc. – what I found lacking was the question of “how”. How do we actually become the sort of people that can actually do what is good? How do we actually become the sort of people that make the tough choices to live out and goodness in our thoughts and our actions? How do we actually learn to walk the walk?

This question of “how” is unglamorous, laborious, and pedantic to answer. It takes a special kind of zealotry to stick with, especially because it requires a tremendous amount of context setting and when you’re done all the work you’ve done seems so obvious, cliché even. And yet, the question of how – how we become good people is so essential.

Perhaps that’s why philosophers don’t seem to emphasize it, but parents and coaches do. Coming up with the “what” is sexy, cool, flashy, and novel and once you lay down the what, it’s easy to walk away and leave the details to the “lesser minds” in the room. On the contrary, you have to care deeply about a person to get into the muck of details to help them figure out “how” to do anything. Figuring out the how is a much longer, arduous, and entangled journey.

This passage is from a book I’ve drafted and am currently editing. To learn more and sign up to receive updates / excerpts click here.

Coaching Requires Dedicated, intensely Focused Time

The biggest error of coaching - not being intentional about it - can be avoided by dedicating real time to it.

People develop faster when they are coached well, but coaching doesn’t happen without intent. To be a better coach, start with making actual “coaching time” that is intentional and intensely focused.

First, as a manager, we must dedicate one-to-one time with whomever we are trying to coach. 30 minutes per week, used well, is enough.

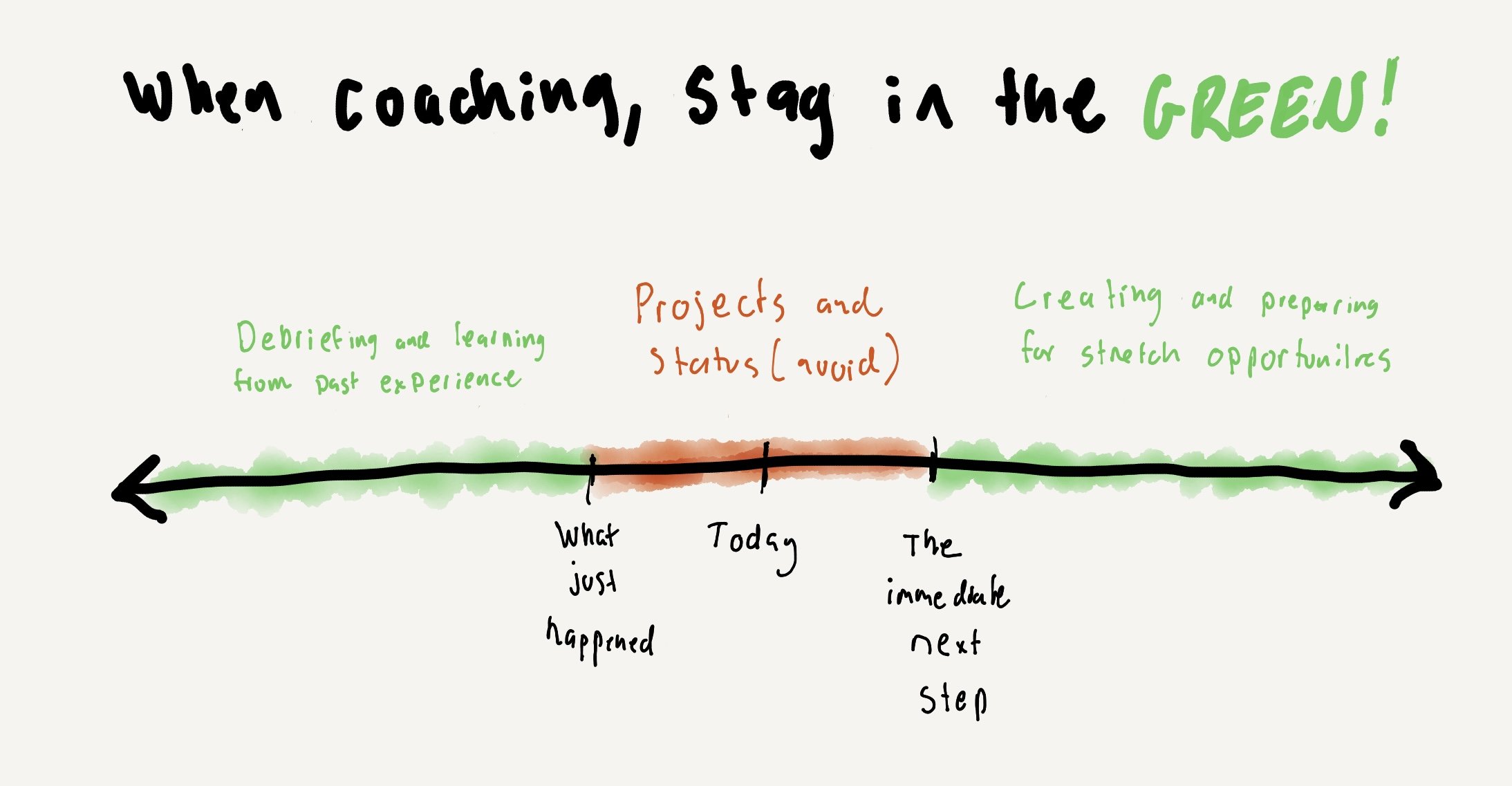

Second, that time can’t be about projects or status. It has to be spent on debriefing to glean learnings from past performance, or on how to create and prepare for future stretch opportunities.

Find a better way to manage status and project work than during a 1-1 and dedicate that time too and use it with intense focus. Personally, I like daily stand-ups from Agile/Scrum methodology and a once weekly full project review with the whole team.

Then, set a rule that during the dedicated time you will not talk about project status or the daily grind of work. If you dedicate time and hold firm to that rule, you’ll end up having a productive coaching conversation. Here are four questions that I’ve found work well to structure a 30-minute coaching conversation.

On a scale of 1 to 100, what percent of the impact you think you could be making are you actually making? (2-4 minutes)

Compared to last week, is your rate of growth accelerating, decelerating, or about the same? (2-4 minutes)

What do you want to talk about? (20-25 minutes)

What’s something I can do to help you feel respected and supported? (2-4 minutes)

This concept applies broadly: whether it’s coaching our team at work, our kids, our students, a volunteer group we’re part of, or co-coaching our marriage together with our partner, we must dedicate and focus the time. In my experience, the results of that dedicated time are exponential after just a few weeks.

Don’t Work Saturdays

Don’t waste the magic of Saturday mornings with work.

As a young twenty-something, I had a friend from work who told me one time that he went to great lengths to avoid working on Saturdays. It was some of the best advice I’ve ever received, and was provocative given that at the time both of us worked for a consultancy that required long hours and many of our colleagues bragged about how many hours they logged.

And what fortuitous advice to get from a peer at a such a formative time in my professional life. I started to avoid work on Saturdays and I still do. And thank God for that. Saturday mornings are a sacred time.

To some extent, I think I always knew this, or at least acted as if they were by accident.

If you grew up in the Midwest or went to college here, you know that our ritualistic observance and respect of Saturday mornings runs deep, and might as well be explained by “something in the water.” Because, after all, we have college football.

This observance and participation in the magic of saturday morning college football started when I was a pre-teen. I remember little of what happened when I was 10, except for the herculean Michigan team that won the National Championship. I still remember Charles Woodson, Brian Griese, and many of the key plays of that season. Every week I would get up, watch the pre-game show and then the game. That was that. No exceptions. Saturday mornings. That’s just what we do.

This continued, obviously, when I showed up for college in Ann Arbor and learned the true glory and glee of a collegian’s tailgate. When we lived in the fraternity house, we’d rally the brotherhood, and march down the street to a nearby sorority house - as if we were part of a parade - trays of Jell-O shots in hand. We’d then rouse the sorority sisters from sleep, with said Jell-O shots before continuing to the senior party house by the football stadium where the tailgate had already begun, and the streets had already started filling with sweatshirts and jerseys laden with maize and blue.

It’s absolutely magical, and for some borders on being a quasi-religious experience if you can believe that. Saturday mornings are a sacred time.

Buy Saturday morning magic extends far beyond football. There were the summers in Washington D.C., for example, where I interned every year of college. We lived in the George Washington University dorms, with about 50 other Michigan undergrads and the few others living down the halls from smaller schools that we’d adopted.

The morning would always start slow, and we’d have an invite for everyone to venture through our open door and brunch on some pancakes that my roommates and I had made, catching up about the latest stories made into zeitgeist by the The Washington Post, the pubs folks had visited the night before, the latest policy paper from a think tank making the rounds, or plans for sightseeing over the weekend.