Deregulating Parenting

There’s a secular lesson to take from Matthew 11: don’t over-regulate children. I want to try, at least, to simplify.

Our parish’s pastor, Father Snow, is about my height. Which means that he’s far shorter than an NBA prospect, though some students at his former parish - Creighton University - were indeed NBA prospects.

Today at mass, our Father Snow gave a homily on Matthew 11: 21-25 which was today’s Gospel reading. To start, he shared an anecdote from his experience at Creighton.

An angry parishioner was lecturing Father Snow about an annulment that she thought the Church shouldn't have given. She was fuming over this application of rules. So much so that one of his giant basketball-playing parishioners stepped in. Putting his elbow on Father Snow’s shoulder, he facetiously asked, “Want me to take her down, Father?”

Father Snow could tell the story better than me, but his point was that too much focus on rules and compliance can be overwhelming. When we fixate on rules they place a heavy burden upon us, chaining us to a slew of anger and stress.

Today’s Gospel reminds us, he said, that Jesus really only had two rules, the first and second greatest commandments: Love God and Love thy neighbor. That’s it. Just two.

In contrast to the 600+ laws imposed upon the Jewish people by the Pharisees, following just two laws is a significantly lighter burden. While this lesson and Gospel reading hold theological and spiritual implications, my immediate takeaway was secular: I impose too many laws on my children.

I have so many rules that underly my parenting. I say “no” all the time, for every little thing it seems, some days at least. If I put myself into the shoes of our sons, I would feel heavy, suffocated even by the grind of the complex, nagging structure of laws I’m imposing.

Surely, a house needs rules about things like not eating ice cream three times a day or not running around naked. But if I’m saying no a hundred times a day, which I think I do sometimes, probably means I’ve gone over the top.

My secular reflection exercise from this biblical lesson - to lighten the burden of rules and laws - was to see if I could simplify my regime of parental law. I wondered, could I get my parenting principles down to two or even just three?

These three are what I came up with. These three principles - be honest, be kind, and learn from your mistakes - can govern every standard I set as a parent.

I’m not trying to advocate for these three rules to become yours if you’re a parent or caregiver, though they fit terrifically for me as a parent. If you like them, steal them.

The more important point I’d advocate is for you to try the exercise. If you’re a parent, caregiver, or even a manager to a team at work, what are the 2-3 principles that you expect others to follow that will govern every standard you set?

It’s not as important what the principles are, as long as they're thoughtful and intentional. What matters the most is that we simplify the burden of our household law to a few principles rather than hundreds.

Even just today, reducing my laws to these three principles has been liberating for me. Instead of trying to regulate every of our sons’ behaviors, I could focus on honesty, kindness, and learning from mistakes.

For example, instead of saying, “stop calling your brother stupid dummy,” I could let this question hang in the air: “It’s important to be kind. Is that language kind?” Instead of having mistakes feel like failure, I could reinforce something they learned. Today it was about how to be kind when sharing food. Tomorrow it can be something else.

I understand that changing my parenting approach will be challenging. After relying on processes and rules for 5 years to establish standards, transforming my behavior will not happen overnight. While every parent is different, I’m confident I’m not the only one who struggles with this.

We can focus on essential principles and free ourselves and our children from a long list of rules by de-regulating parenting. I know I should.

If you try to get your parenting down to a few principles, I’d love to compare notes with you. Please leave a comment or contact me if you give it a go.

—

For those interested, here’s some context for the three principles I’ve been playing with. Again, the point is not to copy the principles exactly, the point is to think about what our, unique, individual ones will be. I wanted to share for two reasons: putting my thoughts into writing helps me, and, I always find it helpful to see an example so I assume others may also find it helpful.

Boys, I have been meditating on it and I don’t want to be a parent that’s obsessed with rules and policing your behavior. One, it won’t work. Two, policing your behavior will not allow you to learn to think for yourself. Three, the level of stress, anger, arguing, and effort required - for me and for you all - having a highly regulated house will be a heavy burden.

I think I’ve come up with three principles that encapsulate the standard of what I expect from myself as a member of this family and community. These are the guiding principles I will use to raise and mentor you. I hope that by centering on three principles that get to the core, we can avoid having dozens upon dozens of rules in our house. Here is what they are.

Be honest.

Honesty is the greatest gift you can give yourself. Because if you are honest, you can have trust and confidence in your own beliefs. And that confidence that your own beliefs and observations about reality are true prevents your soul from questioning itself on what is real. There are no small lies - the uncertainty and pain that lies cause is predictable and omnipresent. One principle between me and you all is to be honest.

Be kind.

Kindness is the greatest gift, perhaps, that you can give to the world. Because if you are kind, you can have trusting relationships with other people. If you are kind, your actions are a ripple effect, making it safer for other people to be kind - and a kind world is a much more pleasant one to live in. Finally, by being kind to others, you can also learn to be kind to yourself. One principle between me and you all is to be kind.

Learn from your mistakes.

Mistakes are part of the plan. They aren’t bad. Quite the opposite - if you’re not making mistakes doing things that are hard enough to learn from or that make an impactful contribution to the world. Mistakes are a feature, not a bug. If we have this posture, it’s essential to learn from your mistakes. Because if you make mistakes and never learn from them, you’ll hurt yourself and others. If you don’t learn from smaller mistakes, you’ll eventually make catastrophic, irreversible mistakes. One principle between me and you all is to learn from your mistakes.

These three principles: be honest, be kind, and learn from your mistakes are our compact. I promise to put in tremendous effort and emotional labor to live by these words that I expect of you. I will hold you to these principles as a standard, but I also promise to help you grow, learn, and develop into them over the course of your life.

Our word is our bond, and these words, my words, are a bond between us.

The dance between expression and empathy

The game escalated real quick.

I was in the backyard gardening and weeding. Suddenly, Myles was zooming around as Gecko and deputized me as Catboy, which are both characters in PJ Masks, one of his favorite television shows.

Within minutes, we were both zooming around, in character, from end to end across the backyard. Myles quickly made the Fisher Price table the Gecko-mobile and Robyn's minivan our headquarters. For nearly 20 minutes, Myles, with a full-toothed smile, would proclaim, “to the Gecko-mobile!”, giggling every time.

About 10 minutes into the game, I realized Myles wasn’t pretending. The table was actually the Gecko-mobile and Robyn’s whip was actually our Headquarters. The world inside his head had become real. Myles had fully expressed his inner world and made it his and my outer world.

—

When disappointed, Myles lets out a sound that we call "the shriek," which resembles the yelp of a pterodactyl.

Recently, this happened when we were scrambling to get to Tortola for a family vacation that was two years in the making. The airline canceled our 6:00 AM flight at 6:00 PM the night before. So we rushed, mobilizing within 90 minutes, to rent a car so we could go to Cleveland to make a flight the next morning. But after waiting in line at Avis for an hour, we discovered that the airline only rebooked half our party. At 11pm, after hours of scrambling, we told the kids we may not be going to the beach.

The news took a minute to sink in. And then, as we started to all head back to the airport parking lot, we heard it - the shriek reverberated and echoed off the surrounding concrete. Honestly, all eleven of us wanted to shriek a little.

The shriek moment was the inverse of our afternoon playing PJ Masks in the backyard. This time, Myles internalized the realities of the outer world and his inner world transformed because of it.

—

We all face this predicament. Our inner and outer worlds are constantly in tension.. Sometimes, we want to take our inner world and impose it on our outer world - this is what we call expression.

Other times, we take the realities of the outer world and allow them to shape our inner world - this is what we call empathy.

Our day-to-day lives are a constant negotiation to bring our inner and outer worlds into balance. It’s a dance between the two worlds we all occupy.

Failing to dance and balance our inner and outer worlds has dire consequences.

If we express too much of our inner world onto the outer world, it oppresses those around us. If we don’t express enough of our inner world, we end up subduing and subjugating our own souls.

Excessive empathy and external influences can overwhelm and crush us. But if we empathize too little, we must sacrifice intimacy and human connection.

We have a choice. We can either snap from the tension between our inner and outer worlds, or we can learn to dance the dance which brings our worlds into balance.

I suppose there’s a third choice, but I think it’s the worst option of the three: suppress and numb. When the tension between our two worlds gets too strong, we can just rub some dirt on it. We can distract ourselves with substances or thrilling pleasures. We can pretend our troubles don’t exist.

Maybe suppressing and numbing is okay for a time. I do believe that nothing in the world can take the place of persistence and that sometimes we need to keep calm and carry on. But I have never met a sane person who can live like that indefinitely. Eventually we all snap - it’s just a matter of when.

In retrospect, this is exactly what happened in my early twenties: I suppressed, then numbed, and then eventually I snapped. Only after that snap did I learn to dance.

This is one of our greatest responsibilities we have as parents. Our children need us to help them learn to dance. Otherwise, the only way they will deal with the tension between their inner and outer worlds will be to suppress and numb, or snap. Luckily, as millennial parents, we have the data and research to know and do better.

I aspire to do better for my three sons, so they can navigate the balance between self-expression and empathy, without having to suppress, numb, and eventually snap. Instead, I must help them learn to dance.

Leaders must create profound silence

Imagine walking into a bustling coffee shop. The whirring of espresso machines, heated debates over the latest news, and the clatter of cups and saucers create an overwhelming din. Now, imagine if all those noises were amplified by a microphone and broadcast over a loudspeaker as you sipped your coffee.

But finally, imagine if someone in the middle of this chaos could flick a switch, transforming the noise into a hum, the hum into a whisper, and finally, the whisper into silence. Suddenly, in the quiet, you can hear the person next to you, the words of a book being read aloud, or even your own thoughts. This is the power of creating silence.

We live in a world of ceaseless noise. At work, we often find that the louder we are – the more assertive in meetings, the more vocal in lobbying for promotions, the more boisterous in attracting customers and followers – the more recognition we receive. Particularly in large organizations, there's a perceived correlation between the volume of one's voice and the likelihood of reward.

Likewise, our family and community lives are marked by volume, though less as an incentive and more as a trap. Community meetings frequently devolve into verbal contests of who can yell the loudest. As parents, we often get swept up in hectic schedules and an unending flood of information, resorting to yelling out of sheer desperation to keep things under control.

Then there's social media, which amplifies this noise to near-deafening levels. It equips everyone with a microphone, fostering an environment that rewards those who shout the loudest. I'm not criticizing influencers or social media—a trend that's fashionable to critique these days. I'm merely labeling our day-to-day American life for what it is: incredibly loud.

The usual advice is to promote listening, to foster better listeners in this noisy world. But listening, as underrated as it is, may not suffice. Amid the cacophony of voices and plethora of microphones, effective listening becomes an Everest to climb. What we need, in professional settings, at home, or within our communities, is the ability to create silence.

Creating silence differs from listening. Listening involves one person attentively comprehending and empathizing with another—a personal act. On the other hand, creating silence entails reducing the ambient noise, enabling everyone in that space to hear and listen. While listening is a two-person tango, creating silence resembles providing noise-cancelling headphones for the entire room.

So, what does 'creating silence' look like? At work, it might be the pause in a meeting that encourages thoughtful responses, allowing even the quietest person to be heard and respected. It could be a company creating a safe space for critical feedback or praise from its customers and partners. It's the breakthrough idea emerging during a moment of quiet reflection in a workshop. It's a team communicating so effectively that members eagerly anticipate meetings or even deem them unnecessary.

In our homes and communities, creating silence might be even more crucial. It happens when those in power amplify the voices of the less powerful—be it our children or marginalized groups. It's when community leaders stay calm and receptive, encouraging constructive dialogues even when faced with challenging questions. It's the genuine connection made during a family dinner where everyone feels comfortable enough to discuss their week, free from platitudes and arguments.

Creating silence requires a particular kind of swagger—not an arrogant narcissism, but a quiet confidence stemming from self-belief and humility. Only when we are secure within ourselves can we create the silence that allows others to flourish.

Creating silence isn't without challenges, though. It could be misconstrued as suppressing voices or dismissing dissent. In our quest for quiet, we might unintentionally stifle vibrant discussion or inhibit creative conflict. The genuine creation of silence isn't about muffling noise but about cultivating an environment where every voice gets a chance to be heard without being drowned out. It's about discerning when to speak, when to listen, and when to simply relish the silence.

There's also a risk of silence being associated with absence or inactivity. In our fast-paced world, we're conditioned to see quiet as wasted time or empty space needing to be filled. We must remember that silence isn't emptiness but a space full of potential. In silence, we find room to think, reflect, and connect on a deeper level.

Perhaps the concept of creating silence has never been as vital as it is now, given our world's unprecedented noise levels. And why is it so crucial? Because silence makes space for collaboration and connection. We can't collaborate or build relationships unless we hear each other. Even the best listener can't function if they can't hear. That's why we must create silence.

So, where do we start? Like most things, we start with ourselves. We begin by creating silence within our own minds. We can work to silence catchy songs, the hum of to-do lists, or our own inner critics. Whether it's through meditation, self-expression, therapy, or exercise, we need to create silence so we can listen to ourselves.

But we mustn't stop there. Our teams, families, and communities need us to create enough silence so that the shouting subsides. Then we can stop worrying about being heard and truly begin to listen.

As we learn to create this silence, let's maintain an open dialogue about what works and what doesn't. Because in a world that's becoming louder, it's not just about who can shout the loudest, but also about who can create the most profound silence.

How to build a Superteam

Superteams don’t just achieve hard goals, they elevate the performance of teams they collaborate with.

In today's dynamic business landscape, the concept of building high-performing teams and managing change has been extensively discussed in management and organization courses.

However, as I've gained real-world experience, I've come to realize that the messy reality we face as leaders is far different from the pristine case studies we encountered in school. Collaborating with other teams, even within high-performing organizations, presents unique challenges that demand a fresh perspective.

The Dilemma of Collaboration for High-Performing Teams

As high-performing teams, we often find ourselves operating within larger enterprises, requiring collaboration with teams from other departments and divisions. However, the reality is that not all these teams are high-performing themselves, which poses a significant challenge. Most enterprises lack the luxury of elite talent, and even the most high-performing teams can burn out if burdened with carrying the weight of others.

Over time, organizations tend to regress to the mean, losing their edge and succumbing to stagnation. If we truly aspire to change our companies, communities, markets, or even the world, simply building high-performing teams is not enough. We must contemplate the purpose of a team more broadly and ambitiously.

What we need are Superteams.

As I define it, a Superteam meets two criteria:

A Superteam is a high-performing team that's able to achieve difficult, aspirational goals.

A Superteam elevates the performance of other teams in their ecosystem (e.g., their enterprise, their community, their industry, etc.).

To be clear, I mean this stringently. Superteams not only fulfill their own objectives and deliver what they signed up for but also export their culture. Through doing their work, Superteams create a halo that elevates the performances of the people and partners they collaborate with. They don't regress to the mean; they raise the mean. Superteams, in essence, create a feedback loop of positive culture that is essential to make change at the scale of entire ecosystems.

One way to think of this is the difference between a race to the bottom and a race to the top. In a race to the bottom, the lowest-performing teams in an ecosystem become the bottlenecks. Without intervention, these low-performing teams repeatedly impede progress, wearing down even high-performing teams. Eventually, the enterprise performs to the level of that sclerotic department. This is the norm, the race to the bottom where organizations get stale and regress to the mean.

Superteams change this dynamic. They export their culture to those low-performing teams that are usually the bottlenecks in the organization, making them slightly better. This improvement gets, reinforced, and creates a transformative, positive feedback loop. As other teams achieve more, confidence in the lower-performing department grows. This is the race to the top, where raising the mean becomes possible.

The biggest beneficiary of this feedback loop, however, is not the lower-performing team—it's actually the Superteam itself. Once they elevate the teams around them, Superteams can push the boundaries even further, reinvesting their efforts in pushing the bar higher. This constant pushing of the boundary raises the mean for everyone, ultimately changing the ecosystem and the world.

How to Build a Superteam

The first step to building a Superteam is to establish a high-performing team that consistently achieves its goals. Moreover, a Superteam cannot have a toxic culture since it is difficult, unsustainable, and dangerous to export such a culture.

Scholars such as Adam Grant, who emphasizes the importance of fostering a culture of collaboration, have extensively studied how to build high-performing teams with positive cultures. Drawing from their work, particularly in positive organizational scholarship, we can further expand our understanding of Superteams.

In addition to the exceptional work of these scholars, it is essential to focus on the second criterion for a Superteam: elevating the performance of other teams in the ecosystem. How can a team work in a way that raises the performance of others they collaborate with? To achieve this, I propose four behaviors that make a significant difference.

First, a Superteam must act with positive deviance. Superteams should feel materially different from average teams in its ecosystem. Whether in composition, meeting structures, celebration of success, language, or bringing energy and fun, Superteams challenge conventions. Such explicit differences not only generate above-average results but also create a safe space for others to act differently.

Second, a Superteam must be self-reflective and constantly strive to understand and improve how it works. Holding retrospectives, conducting after-action reviews, or relentlessly measuring results and gathering customer feedback allows Superteams to make adjustments and changes with agility. This understanding of internal mechanics and the ability to transmit tacit knowledge of the culture enable every team member to become an exporter of the Superteam's culture.

Third, a Superteam walks the line between open and closed, maintaining a semi-permeable boundary. While being open and transparent is crucial for exporting the team's culture, maintaining a strong boundary is equally important. Being overly collaborative or influenced by the prevailing culture can hinder positive deviance. Striking the right balance allows Superteams to create space for exporting their culture while protecting it from easy corruption.

Finally, a Superteam must act with uncommon humility and orientation to purpose. By embracing the belief that "you can accomplish a lot more when you don't care who gets the credit," Superteams prioritize the greater purpose of raising the mean instead of seeking personal recognition. This humility allows them to make cultural improvements without expecting individual accolades, empowering others to adopt and embrace the exported culture.

Over the years, I've become skeptical of mere "culture change initiatives." True culture change requires more than rah-rah speeches and company-wide emails. Culture change demands role modeling and the deliberate cultivation of Superteams. Any team within an ecosystem can change its culture and aspire to build Superteams that export their culture, ultimately transforming the world around them for the better.

Resistance against easy

The easy path is attractive. But what would that make me? What would that make us?

At my angriest or most exhausted especially, I question whether my effort to do the right thing makes a difference.

And then I wonder if I should be a bit more “flexible” in how I choose to act. Because…

…I could angle for a promotion by courting competing offers that I never intend to take.

…I could get my colleagues to bend to my will by shaming them a little during a team meeting, sending a nasty email, or politicking with their boss.

…I could yell more at my kids or threaten them with no more ice cream.

…I could pawn domestic responsibilities off on my wife or run to my parents to bail me out.

…I could adhere to a rule of “no new friends” and prioritize the relationships in my life based on social status or what that person can do for me.

…I could say “because I said so”, much more.

…I could make all my blog posts click bait or say things I don’t actually believe to get more popular.

…I could find reasons to take more business trips or weekends with buddies to get away.

…I could play with facts to make them more persuasive.

…I could keep my head down if I notice little problems or injustices that others don’t.

…I could stop listening or talk over quieter people so that I can be heard.

…I could just throw away the toys the kids leave all over the floor.

…I could tear down others ideas, with no viable alternatives, to gain supporters.

…I could, literally, sweep dust under the rug.

…I could do these things to make it a little easier.

Lots of people do, right?

And honestly, I for sure still fail my better angels no matter how hard I try. I’m no perfect man, especially when it it comes to that one about yelling at my kids (yikes).

But damn, if I did shit like this on purpose, what would that make me?

“But what would that make me?” is all I need to ask myself when I want to stop trying so hard. That sets me straight when I want to loosen up a little on principles.

I share all this because I’m feeling the weight of the daily grind a little extra today. And I know I’m not the only one who fights the urge to compromise on their principles, even just slightly.

We could. But what would that make us?

Thank you teachers, for being the rain

Thank you, teachers, for everything you do and have done - for me, for our three sons, and for all children. We have all yearned for the rain to drench our gardens, and you have made it pour.

The job of a gardener, I’ve realized three years into our family’s adventure planting raised beds, is less about tending to the plants as it is tending to the soil.

Is it wet enough? Are there weeds leeching nutrients? Is it too wet? How should I rotate crops? Is it time for compost? Are insects eating the roots? As a gardener, making these decisions is core to the craft.

The plants will grow. The plants were born to grow, that’s their nature. But to thrive they require fertile soil. That’s essential. And as a home gardener, ensuring the soil’s fertility is my responsibility.

Gardening is not just a hobby I love, it’s also one of my favorite metaphors for raising children. The connection is beautifully exemplified by a German word for a group of children learning and growing: kinder garten.

The kids will grow, but they rely on us to provide them with fertile soil.

And so we do our best. We cultivate a nurturing environment, providing them with a warm and cozy bed to sleep in. We diligently weed out negative influences, ensuring their growth is not hindered. Just as we handle delicate plants and nurture the soil, we handle them with gentle care, aware of their tenderness. And of course, we try to root them in a family and community that radiates love onto them as the sun radiates sunshine

If we tend to the soil, the kids will thrive.

Well, almost. The kids will only flourish if we just add one more thing: rain.

Without rain, a garden cannot thrive. While individuals can irrigate a few plants during short periods without rainfall, gardeners like us can’t endure months or even weeks without rain. Especially under the intense conditions of summer heat and sun, our flowers and vegetables struggle to survive without rainfall. The rain is invaluable and irreplaceable.

As the rain comes and goes throughout the spring and summer, it saturates the entire garden bed, drenching the plants and the soil surrounding them. The sheer volume of rainwater is daunting to replicate through irrigation systems; attempting to match the scale of rainwater is financially burdensome. Moreover, rain possesses a gentle touch and a cooling effect. It nourishes the plants more effectively than tap water.

For all these reasons, rain is not something we merely hope for or ask for - rain is something we fervently pray for.

It's incredibly easy to overlook and take for granted the rain. It arrives and departs, quietly watering our garden when we least expect it. Rain can easily blend into the backdrop, becoming an unscheduled occurrence that simply happens as a part of nature's course.

When we harvest cherry tomatoes, basil, or bell peppers, a sense of pride and delight fills us as we revel in the fruits of our labor. The harvest brings immense satisfaction and a deep sense of pride, even if our family’s yield is modest and unassuming.

As we pick our cucumbers, pluck our spinach, or uproot our carrots, it rarely occurs to me to credit the rain. And yet, without the rain, our garden simply could not be.

In the lives of our children and within our communities, teachers serve ASC the rain. And by teachers, I mean a wide range of individuals. I mean the educators in elementary, middle, and high schools. I mean the pee-wee soccer coaches. I mean the Sunday school volunteers. I mean the college professors engaging in discussions on derivatives or the Platonic dialogues during office hours. I mean the early childhood educators who infuse dance parties into lessons on counting to ten and words beginning with the letter "A".

I mean the engineer moms, dads, aunts, and uncles who coach FIRST Robotics, or the recent English grads who dedicate their evenings to tutoring reading and writing. I mean the pastors and community outreach workers showin’ up on the block day in and day out. I mean the individuals running programs about health and nutrition out of their cars. I mean the retired neighbors on their porch who share stories of their world travels and become cherished bonus grandparents. I mean the police officers and accountants who serve as Big Brothers and Big Sisters despite having no obligation to do so.

I mean them all and more. These people, these teachers, are the rain.

They find a way to summon the skies and shower our kids with nourishing, life-giving rain. As a parent and a gardener nurturing the soil in which children are raised, I cannot replicate the rain that teachers provide. Without them, our children simply could not flourish.

Candidly, this is also a personal truth. I have greatly relied on and benefited from numerous teachers throughout my life. It has all come full circle for me as I've embraced the roles of both a parent and a gardener. Witnessing our children learn, grow, and thrive under the guidance of teachers has been a humbling revelation. I've come to realize that without teachers, my own growth and development would not have been possible. Without teachers, I simply would not be.

This time of year is brimming with graduations - whether they're from high schools, colleges, or even from Pre-K like our oldest just graduated from this weekend. Much like the bountiful harvest, it is a time for joyous celebration. Our gardens have yielded fruit, and we should take pride in our dedicated efforts.

But in this post, I also wish to honor all of the different types of teachers out there. They have been the gentle, nurturing rain - saturating the soil and fostering a fertile environment for our children to flourish.

Thank you, teachers, for everything you do and have done - for me, for our three sons, and for all children. We have all yearned for the rain to drench our gardens, and you have made it pour.

Photo by June Admiraal on Unsplash

The parenting cheat code(s)

The keys are sleep and paying attention. So obvious, but so elusive.

In retrospect, it seems so obvious that sleep and paying attention are crucial. If parenting were a video game, these would be the two cheat codes.

First, there’s plenty of data out there now that affirms how important sleep is. But as parents, we already know this, intimately, from lived experience. It’s obvious. When I don’t sleep enough, I am cranky and short-tempered. When the kids don’t sleep enough they are cranky and short-tempered. When we sleep, it’s a night and day difference—our household functions so much better when we sleep.

And then there’s paying attention. Again, there’s lots of data that emphasizes the importance of intimate relationships and being deeply connected to others. As parents, we also know this so well from lived experience. How many times a day have you heard, “Watch this, Papa”, “Papa, look at me in my pirate ship”, or worst of all, “Can you stop looking at your phone, Papa?”

When kids aren’t paid attention to, they literally scream for it. They fight to be loved and paid attention to, as they should—cheat code.

And as I’ve reflected on it over the years, these seem to be cheat codes for much more than parenting. It’s as if sleep and paying attention in the moment are cheat codes for a healthy, happy, and meaningful life.

In marriage, we are better partners and more in love when we sleep and pay attention. At work - sleep and paying attention boost performance and build high-performing teams. In friendships, the cheat codes still apply. In spiritual life, it’s the same thing. Sleep and paying attention are cheat codes.

And still, I almost blew it. I messed up for the first few years of Bo’s life. I didn’t get enough sleep. And I was too obsessed with work to pay attention him, fully, when I was home. I often missed stories and tuck-ins. My mind was itching to scratch off items on my to-do list and obsessing over the man I wanted to become in the eyes of others.

And the worst part, the one that makes me want to just…retreat, and trade a limb if I could, is that I remember so little of him as a newborn. I don’t remember how he laughed and giggled at 9 months old, barely at all. I don’t remember more than a handful of games we played together, maybe just peek-a-boo and “foot phone”. Damn, I am so sad, and weeping, as I pen this. I was there, but I still missed out.

I want so badly, for the man I am now to be baby Bo’s papa. Because at some point in the past two years, with a lot of help, I figured this out. I figured out the cheat codes—but, my tears cannot take me back. I have no time machine, no flux capacitor. What’s done is done. Damn.

The only consolation I have is that it didn’t take me longer. If I had lived my whole life not sleeping or paying attention—to Robyn, to our sons, to friends and family, or even just walking in the neighborhood and appreciating the trees—I’d probably pass from this world a miserable man with irreconcilable regret and guilt.

Right now, Bo, Myles, and Emmett, you are 5, 3, and 1 years old respectively. Maybe one day you’ll come across this post. Maybe I’ll be alive when you do—I hope so. Or maybe I’ll have gone ahead already, I don’t know.

But if you’re reading this one day, I am so deeply sorry that I messed up, and it took me years to figure this out—to start using these cheat codes I guess you could say. I apologize about this, especially to you Robert. I wasn’t fully there for you in your first 2-3 years.

I hope you all can forgive me. I am not perfect, but I’ve gotten better, and I’m still trying. I hope that by sharing this with you, you can avoid the same mistakes I made.

Photo by Lucas Ortiz on Unsplash

Leadership in the Era of AI

When it comes to the impact of Generative AI on leadership, the sky's the limit. Let's dream BIG.

Just as the invention of the wheel revolutionized transportation and societies thousands of years ago, we might actually stand on the brink of a new era. One where generative AI, like ChatGPT, could transform our way of life and our economy. The potential impact of AI on human societies remains uncharted, yet it could prove to be as significant as the wheel, if not more so.

Let's delve into this analogy. If you were tasked to move dirt from one place to another, initially, you would use a shovel, moving one shovelful at a time. Then, the wheel gets invented. This innovation gives birth to the wheelbarrow—a simple bucket placed atop a wheel—enabling you to carry 10 or 15 shovelfuls at once, and even transport dirt beyond your yard.

But, as we know, the wheel didn't stop at wheelbarrows. It set the stage for a myriad of transportation advancements from horse-drawn buggies, automobiles, semi-trucks, to trains. Now, we can move dirt by the millions of shovelfuls across thousands of miles. This monumental shift took thousands of years, but the exponential impact of the wheel on humanity is undeniable.

Like the wheel, generative AI could be a foundational invention. Already, people are starting to build wheelbarrow-like applications on top of generative AI, with small but impactful use cases emerging seemingly every day: like in computer programming, songwriting, or medical diagnosis.

This is only the beginning, much like the initial advent of the wheelbarrow. Just as the wheelbarrow was a precursor to larger transportation modes, these initial applications of generative AI mark the start of much more profound implications in various domains.

One area in particular where I'm excited to see this potential unfold is leadership. As we stand on the brink of this new era, we find ourselves transitioning from a leadership style that can only influence what we touch, constrained by our own time. Many of us live "meeting to meeting", unable to manage a team of more than 7-10 people directly. Even good systems can only help so much in exceeding linear growth in team performance.

However, with the advent of generative AI, we're embarking on a new journey, akin to moving from the shovel to the wheelbarrow. Tools like ChatGPT can serve as our new 'wheel', helping us leverage our leadership abilities. In my own experiments, I've seen some promising beginnings:

A project manager can use ChatGPT to create a project charter that scopes out a new project outside their primary domain of expertise. This can be done at a higher quality and in one quarter or one tenth of the usual time.

A product manager can transcribe a meeting and use ChatGPT to create user stories for an agile backlog. They could also quickly develop or refine a product vision, roadmap, and OKRs for annual planning—achieving higher quality in a fraction of the time.

A people leader can use ChatGPT as a coach to improve their ability to lead a team, relying on the tool as an executive coach to boost their people leadership skills faster and more cost-effectively than was possible before.

These are merely the wheelbarrow-phase applications of generative AI applied to leadership. Now, let's imagine the potential for '18-wheeler' level impact. Given the pace of AI development, it's plausible that this kind of 100x or 1000x impact on leadership could be realized in mere decades, or possibly even years:

Imagine a project manager using AI to manage hundreds of geographically distributed teams across the globe, all working on life-saving interventions like installing mosquito nets or sanitation systems. If an AI assistant could automatically communicate with teams by monitoring their communications, asking for updates, and creating risk-alleviating recommendations for a human to review, a project manager could focus on solving only the most complex problems, instead of 'herding cats.'

Consider a product manager who could ingest data on product usage and customer feedback. The AI could not only assist with administrative work like drafting user stories, but also identify the highest-value problems to solve for customers, brainstorm technical solutions leading to breakthrough features, create low-fidelity digital prototypes for user testing, and even actively participate in a sprint retrospective with ideas on how to improve team velocity.

Envision a people leader who could help their teams set up their own personal AI coaches. These AI coaches could observe team members and provide them with direct, unbiased feedback on their performance in real time. If all performance data were anonymized and aggregated, a company could identify strategies for improving the enterprise’s management systems and match every person people to the projects and tasks they can thrive, and are best suited for, and actually enjoy.

Nobody has invented this future, yet. But the potential is there. What if we could increase the return on investment in leadership not by 2x or 5x, but by 50x or 100x? What if the quality of leadership, across all sectors, was 50 to 100 times better than it is today?

We should be dreaming big. It's uncertain whether generative AI will be as impactful as the wheel, but imagining the possibilities is the first step towards making them a reality.

Generative AI holds the potential to revolutionize not only computer programming but also leadership. Such a revolutionary improvement in leadership could lead to a drastically improved world.

When it comes to the impact of Generative AI on leadership, the sky's the limit. Let's dream BIG.

Photo by Ēriks Irmejs on Unsplash

The Leadership Trifecta: Management, Leadership, Authorship

What matters is the nuance, because the three affect dynamics at different levels of organization: management affects individual dynamics, leadership affects team dynamics, and authorship affects ecosystem dynamics.

When we choose to lead, the first question we must answer is: who are we leading for?

Are we choosing to lead to enrich ourselves or everyone? Are we doing this for higher pay, social status, career advancement, and spoils? Or, are we doing this to improve welfare for everyone, enhance freedom and inclusion, or better the community?

If you're not in it for everyone (including yourself, but not exclusively or above others), you might as well stop reading. I am not your guy - there are plenty of others who have better ideas about power, career advancement, or gaining increased social status.

But if you're in it for everyone, if you're willing to take the difficult path to do the right thing for everyone in the right way, you probably struggle with the same questions I do, including this big one: what does choosing to lead even entail? Do I need to lead or manage? What am I even trying to do?

Is the goal management or leadership?

For many years, I’ve rolled my eyes whenever someone starts talking about leadership versus management or how we need people to transcend from being “managers” and elevate their game to become “leaders.” In my head, I'd question anytime this leadership vs. management paradigm comes up: “what are we even talking about?”

After many years, I finally have a point of view on this tired dialogue: management, leadership, and authorship all matter. What matters is the nuance, because the three affect dynamics at different levels of organization: management affects individual dynamics, leadership affects team dynamics, and authorship affects ecosystem dynamics.

Management, Leadership, and Authorship

Management, though the term itself is not what matters, can be defined as the practice of influencing individual performance. Think "1 on 1" when considering management. In management mode, the goal is to ensure that every individual is contributing their utmost.

Management primarily influences individual dynamics. Hence, when discussing management, we often refer to directing work, coaching, providing feedback, and developing talent. These are the elements that shape individual performance.

Similarly, leadership can be viewed as the practice of enhancing team performance as a collective unit. Think "the sum is greater than its parts" when contemplating leadership. In leadership mode, the goal is to ensure the team can make the highest possible contribution as a single unit.

Leadership predominantly affects team dynamics, which is why discussions about leadership often involve vision, strategy, culture, and processes. These elements impact the performance of a team functioning as a single unit.

Authorship, however, is the practice of influencing the performance of an entire network of teams and organizations aiming to achieve collective impact, often without formal or centralized coordination.

Authorship has become more feasible in recent history due to the rise of the internet. Unlike 50 years ago, many of us now have the opportunity to consider authorship because we can communicate with entire networks of people.

When considering authorship, think of it as being part of a movement that's larger than ourselves. In authorship mode, the goal is to mobilize an entire network to benefit an entire ecosystem - whether it's an industry, a community, a specific social issue or constituency, or in some cases, society as a whole. The aim is to ensure that the entire network is making the highest possible positive contribution to its focused ecosystem.

Authorship primarily affects ecosystem dynamics. That's why, when I ponder authorship, I think about concepts like purpose, narratives, opportunity structures, platforms, and shaping strategies. These elements influence entire networks and mobilize them to create a collective impact, particularly when they're not part of the same formal organization.

To illustrate, consider a software development company. In the context of management, the team lead may ensure every developer is performing at their best by providing guidance, setting clear expectations, and offering constructive feedback.

When it comes to leadership, the same team lead would be responsible for setting the vision for their team, aligning it with the company's goals, creating a positive team culture, and facilitating effective communication.

Authorship, however, would usually (but not necessarily) involve the CEO or top management. They would work towards building industry partnerships, contributing to open-source projects, or organizing industry conferences, ultimately aiming to influence the broader tech ecosystem, perhaps to achieve a broader aim like improving growth in their industry or solving a social problem - like privacy or social cohesion - through technology.

It all boils down to three questions:

Management question: On a scale of 1 to 100 how much of my potential to make a positive impact am I actually making?

Leadership question: On a scale of 1 to 100, how much of our team’s potential to make a positive impact are we actually making?

Authorship question: On a scale of 1 to 100, how much of our potential positive impact are we making, together with our partners, on our ecosystem or the broader world?

To assess your potential impact on a scale from 1 to 100, start by understanding the maximum positive impact you, your team, or your ecosystem could theoretically achieve. This '100' could be based on benchmarks, best practices, or even ambitious goals. Then, honestly evaluate how close you are to that maximum potential. This is not a perfect science and will require introspection, feedback, and perhaps even some experimentation. The important thing is to have a reference point that helps you understand where you are and where you could go.

In my own practice of leading, these are the questions I have been starting to ask myself and others. These three questions are incredibly helpful and revealing if answered honestly.

To really make a positive impact, I’ve found that it’s important to ensure all three dynamics - individual, team, and ecosystem - are examined honestly. If we truly are doing this to benefit everyone (ourselves included) we need to be good at management, leadership, and authorship.

Developing skills in these three areas isn't always straightforward, but you can start small. The easiest way I know of is to begin asking these three questions. If you’re in a 1-on-1 meeting or even conducting your own self-reflection, ask the management question. If you’re in a weekly team meeting, ask the leadership question. If you’re meeting with a larger team or a key partner, ask the ecosystem question.

Beginning with honest feedback initiates a continuous improvement engine that leads to enhancement in our capabilities of management, leadership, and authorship.

In conclusion, whether we're discussing management, leadership, or authorship, it's clear that each plays a crucial role in achieving positive impact. From enhancing individual performance to influencing entire ecosystems, each area has its distinct but interrelated role. As leaders, our challenge and opportunity lie in understanding these nuances and developing our capabilities in all three areas. Remember, it's not about choosing between management, leadership, and authorship - it's about embracing all three to maximize our collective potential.

I'd love to hear your thoughts on these three aspects of leading - management, leadership, and authorship. How have you balanced these roles in your own leadership journey? What challenges have you faced? Feel free to share your experiences and insights in the comments below or reach out to me personally.

Photo by Aksham Abdul Gadhir on Unsplash

The silhouette of brotherhood

I’m witnessing a brotherhood form. This is my deepest joy as a father.

It is so obvious how quickly children change. Even a single day after they are born, something changes. They learn and grow immediately. They start to eat, and they quickly discover how to grasp, with their whole hand, the little finger of their father.

Then they smile, sit up, and then crawl and walk. They speak and laugh. They get haircuts and pairs of new light-up velcro shoes and they learn to hold their breath while swimming.

They were born to change, truly. And it does happen fast. But occasionally we’ll notice something, one little thing, that endures a bit. One little, essential, thing about these children that will remain permanent even as they grow, like a thumbprint of their personality.

Something, finally, which is consistent and deeply comforting and helps us find a peaceful, amicable reconciliation with the passing time. I need these little, essential things to stay anchored when the water in our lives gets choppy.

We are at the beach and I am sitting in the sand when Robert catches my eye.

He is about 25 yards ahead of me, at the water’s edge. As he looks out at the the waves I notice his silhouette, the tide splashing past his ankles. I am awestruck by how Robert’s posture and demeanor have remained consistent over the years.

Robert has an empathy and quiet confidence in his posture. His feet are grounded and his back is straight, but there’s a softness to his stance. He stands like an explorer does who has both the anticipation to go where others have not and the humility to appreciate the vastness of the ocean before him. Robert’s silhouette has had a tender graciousness to it his whole life.

Myles is about 10 feet ahead of me and is sitting cross-legged, while building sandcastles with his Grandad. I notice, immediately, the sturdiness in Myles’s back. His posture is upright, erect. His silhouette is eager, bold, and focused. His muscles and frame are sinewy and taut, and he always carries his chest a few degrees forward as if in an athlete’s ready stance.

And yet, just as everything about him is sturdy, Myles also radiates a sense of playfulness and joy - his body moves with a rhythm of jazz music even now, as he plops sand in the bucket shovel by shovel. This mix of intensity and ease gives him an uncommon swagger, I think to myself, which could not possibly have been taught to him - it’s something calm and natural. Myles’s silhouette has always been deliberate and electric, just as it is now, as I watch him fill another bucket with wet sand.

And finally, I turn my gaze to Emmett, who has just crawled out from between my legs to be closer to the action of the sandcastle factory in front of me. Even at just one year old, Emmett’s unique qualities are already starting to emerge. Emmett’s posture is open and gregarious. His arms and his legs, even while sitting on the beach, are spread out as if he’s giving the breeze and the sunshine a hug as he giggles.

Emmett’s silhouette is like a starfish, always reaching and spreading his limbs and fingers to wave at, greet, and smile outwardly to the whole world. Already, I can tell that within Emmett there is an enduring openness, friendliness, and dynamic warmth. This is a truth his silhouette is already revealing.

These are the silhouettes of my three sons. What I am seeing is my three sons. And even though so much of who they are and who they will be is not yet decided, I am seeing something essential about them. There is something of them that is already drawn. Something that will not change. And what is already drawn is something unique and something good.

And then I snap back to the moment. The children laughing, the friends, the sand, the waves, and the horizon all come back into focus. I’m back here, sitting on the beach.

But then I remember some of the other wonderful silohouttes I’ve seen throughout this day at the beach and this trip - like when Myles and Robert were walking hand in hand down the boardwalk, or when the three of them were dog-piling on the floor laughing and tickling each other, or when they were all right in front me me working on the same sandcastle.

What I’m seeing is a bond being formed. As I watch my three sons play and explore the world together, their individual silhouettes are blending together to form a beautiful, harmonious picture of brotherhood. Witnessing this is what fills my heart the most.

There have been so many moments during this trip where I see them together, the lines of their silhouettes and complementary postures all within one frame. What gives me the deepest pleasure as a father is seeing the Tambe Brothers become a silhouette of it’s own.

And deep down, I accept their relationship with each other will grow and evolve. They’ll tussle and wrastle and have spats from time to time. I know this.

I know that their bond as brothers will never again be the same as it is now. Time will, despite my best efforts and sincerest prayers, continue to pass.

But I know, too, that something about this scene in front of me won’t change. Something of their brotherhood is already drawn and will endure, even after we are gone. I find comfort in this. This is the anchor I am looking for.

This image of the three of them together, in a bond of harmonious brotherhood, is the silhouette I treasure the most.

Photo by Pichara Bann on Unsplash

Reverse-Engineering Life's Meaning

Finding meaning is an act of noticing.

It's difficult to directly answer questions like "why am I here," "what is the meaning of my life," or "what's my purpose." It may even be impossible.

However, I believe we can attempt to reverse-engineer our sense of meaning or perhaps trick ourselves into revealing what we find meaningful. Here's how I've been approaching it lately.

Meaning, it seems, is an exercise in making sense of the world around us and, by extension, our place in it.

Instead of tackling the big question head-on (i.e., what's the meaning of my life), we can examine what we find salient and relevant about the world around us and work backward to determine what the "meaning" might be.

Here's what I mean. The italicized text below represents my inner monologue when contemplating the question, "What is the world out there outside of my mind and body? What is the world out there?"

The world out there is full of people, first and foremost. It teems with friends I haven't made yet, individuals with stories and unique contributions. Everyone has a talent and something special about them, I just know it. The world out there is full of untapped potential.

The world out there also contains uncharted territory. There is natural beauty everywhere on this planet. It is so varied and colorful, with countless plants, animals, rocks, mountains, rivers, and landscapes. The world out there is wild. Beyond that, we don't even know the mysteries of our own oceans and planet, let alone our solar system or the rest of the universe. The world out there is a vast galaxy filled with natural beauty and wonder.

But the world out there has its share of senseless human suffering, often due to our own mistakes and the systems we strive to perfect. There is rampant gun violence, hunger, homelessness, anger, and disease—all preventable. The world out there is a mess, but the silver lining is that not all of that senseless suffering is outside our control. We can make it better if we do better.

The world out there also has an abundance of goodness. Many people strive to be part of something greater than themselves. They help their neighbors, practice kindness, teach children to play the piano, visit the homebound, tell the truth, do the right thing, seek to understand other cultures, learn new languages, and strive to be respectful and inclusive. The world out there is full of parks, festivals, parties, and places where people play, eat, and share together. The world out there is generous.

The world out there is also close. My world is people like Robyn, Riley, Robert, Myles, and Emmett, as well as our parents, siblings, family, friends, colleagues, neighbors, and kind strangers. The world out there is our neighborhood, our backyard, our church, our school, and our local pub. It's the people on our Christmas card list and those we encounter around town for friendly conversations. The world out there includes the individuals I pray for during one or two rounds of a rosary. It doesn't have to be big and grand; it's the people I can hug, kiss, cook a meal for, or call just to say "hey."

So, the exercise is simple:

Find a place to write (pen, paper, computer, etc.).

Set a 15-minute timer.

Start with the phrase "The world out there is..." and keep writing. If you get stuck, begin a new paragraph with "The world out there is..." and continue.

After completing this exercise and taking stock of my own answers, I begin to see patterns in my responses that resonate with my day-to-day life. Meaning, for me, involves helping unleash the untapped potential in others, exploring the natural world, dreaming about the universe, fostering goodness and virtue, and being a person of good character. Meaning, for me, also entails honoring and cherishing my closest relationships, both the ones that are close in proximity and deep in their intimacy.

It seems that meaning is not generated in what we think of as our "brain." Our brain manages our body's energy budget, makes decisions, predicts the future, and solves problems. That’s our brain’s work.

Meaning, I believe, is created in our mind. When I think of the mind, I envision it as the function we perform when we absorb the seemingly infinite information about the external world through all five senses and attempt to make sense of it.

Meaning, it appears, is not an abstract thing we have to create. We don't "make" meaning. Instead, we discern meaning from what we find relevant and salient in the world around us. Out of the countless details about the external world, we hone in on certain aspects. The meaning is what bubbles to the top of our minds. We don't have to make meaning; we can just notice it.

This exercise has shown me that we can reverse-engineer our way into discovering meaning. If we can bring to the surface what we believe about the external world, it becomes clear what holds significance for us.

For example, if you find that "the world is full of cities and people, which leads to innovations in business, art, and culture," it's an easy leap to conclude that part of your meaning or purpose likely involves experiencing or improving cities and their cultural engines. If you discover that "the world is full of teachings about God and has a history of religious worship," it's a straightforward leap to deduce that part of your meaning or purpose likely relates to your faith and religious practice.

Being mindful of what we notice about the world is our back door into these abstract and challenging questions about "meaning" or "purpose."

What's difficult about this, I think, is the sheer volume of noise out there. Also, if we accept this perspective on meaning, we must acknowledge that meaning is not static and enduring—if it's discerned by our worldview, then changes in our perspective may also change or even manipulate our notions of meaning.

Many people try to tell us about the world outside of us. This includes companies through their commercials, authors, politicians, artists, philosophers, scientists, and priests—anyone who shares an opinion. Even I do this—if you're reading this, I am also guilty of adding to the noise that shapes your perspective of the external world.

Making sense of our lives is crucial for feeling sane and alive. It would be easy to average out what others around us say about the world out there, but if meaning truly is a discernment of what we notice about the external world, just listening to everyone else would effectively outsource the meaning in our lives to other people.

I don't think we should do that. After all, we live in a country where we have the freedom to speak, think, and make sense of the world for ourselves—what a terrible freedom to waste. Instead, we should be selective about who we pay attention to and listen to our own minds, noticing what they're trying to tell us. We shouldn't outsource meaning; we should notice it for ourselves.

Photo by Dawid Zawiła on Unsplash

Gifts drive culture

Culture often changes with extremely small, risky acts.

Robyn and I, technically, had two weddings. The first, on a Saturday, was celebrated by a priest in an old Catholic Church in Detroit. The church had hand-painted ceilings and huge multi-story pillars made of upper-peninsula timber, wider in diameter than hula hoops. It was beautiful.

The second ceremony was performed by a Hindu pandit, the next day. Shastri Ji is someone I’ve known since the age of 6, when we moved to Metro Detroit and started going to the local Temple. As he performed the Pheras, our marriage rites where we circled an open fire used for the ceremony, he shared two pieces of sage wisdom. I think about regularly.

First, he explained the essence of marriage, simply and with just one word - together, together, together.

Second, he shared an important idea in the Hindu conception of marriage, which explains one reason (among many) of why women are so important. A woman marrying into a family purifies it, not once, but twice - first she purifies her husband, second she purifies the ancestral line through any children she bears.

Marriage, in the way, is an act of double purification.

—

Even though giving a gift, truly and sincerely is difficult - demanding something of our souls - it’s what drives our culture forward.

It seems to me that there are two general ways to improve culture: changing possibilities and changing norms.

Changing possibilities requires an innovation, a new and better way of doing something. In this way refrigerators and democracy are quite similar.

Refrigerators gave a new and better of storing and preserving food, opening up the possibilities of agricultural exports, stretching the reach of the food supply, and culinary exploration for home cooks. Democracy gave a new and better way of governing states, opening up possibilities to mitigate the risk of tyrants and creating the condition of human rights and flourishing.

Changing norms requires a deviant behavior, ideally positive, which by definition is a risky act because it is different. In this way, art and telling someone you love them are quite similar.

Art is a risky act because the artist is bring a point of view, something fresh, that is untested and unusual, which means nobody may like, pay for, or even understand it. Telling someone you love them, obviously, is a risk because if they don’t say it back it’s surely heartbreaking.

The risk is what makes positive deviance so impactful - the deviant bears the social risk of being different, proves that different is possible. This is how norms change.

Innovations have switching costs, which is what makes them feel so sudden, so violent sometimes. Pressure builds, like a tea kettle, and then when the time has come for the better way, it bursts and whistles, jolting the masses into something novel. The nature of culture changing innovations is that of a phase shift.

Gifts can be gradual. They change the culture one conversation and one hug at a time. The effects of gifts layer, and years later we wonder, “how could it have ever been different?”

So many of the littlest moments can be gifts, like when we hear…

“Excuse ma’am, you dropped this,” in the grocery line.

“Good afternoon,” as a neighbor smiles as we pass on the sidewalk.

“Thank you for your leadership,” from a respected colleague.

“I know you like this kind of granola,” from our spouse who went grocery shopping.

“Let me get that for you,” from a shopkeeper who sees our hands are full.

Or “I’m glad you’re here,” from just about anyone at any time.

—

There is a certain agony that comes from buying a present that’s really from the heart. In a moment of Charlie Brown-esque inner turmoil, we think, “dear God, I hope they like it.”

Part of this angst is about the gift itself. There’s a genuine worry that the contents of the package will be pleasing to the person whose day we seek to brighten.

The other half of the angst is that the TLC we put into the gift will be rejected, or wasted. We worry about the risk we have taken, the love that we have wagered in this gift, and whether that piece of our soul that we’ve woven into the wrapping and bow will be seen, or if it will not.

It seems to me that this is what all gifts have in common, even if that gift is simply holding the door open for the stranger in public who happens to also be walking into the Olive Garden for an early dinner.

All gifts are both the content of the gift, plus the social risk taken to give it. When we give a gift that is truly sincere, we acknowledge that our effort may be shunned and proceed anyway.

I think that’s what makes a gift truly special. Perhaps it’s not quite the thought that counts, but the risk that counts even more. We intuitively understand this - we respond emotionally and perhaps unconsciously to the notion that “someone bore all this risk, for me?”

And so too for the giver, they also respond emotionally and perhaps unconsciously to the notion that “I was able to shoulder all this risk, for someone else?”

Gifts, too, are an act of double purification.

—-

I am fascinated by Silicon Valley, the salons of Europe, or even Detroit and New York when Motown and hip-hop were coming on the scene in the back half of the 20th century. How did these creative clusters develop? How did it happen? How did these incredibly vibrant, artistic, and entrepreneurial places emerge?

In Detroit, to be called an “OG”, short for “Original Gangster” is one of the highest signs of respect one can be bestowed with. It doesn’t simply mean, “old person”, it implies some level of experience but also generosity. An OG is someone who not only has the wisdom of experience but the willingness to be a pillar of a community, that others can lean on to grow and thrive.

Being on OG implies that you were not only successful in your own right, but were also responsible for helping the next generation come up behind you.

I think it’s these OGs, who are often working behind the scenes in a community, that are the unsung heroes of these creative cluster. What would Silicon Valley be without the cadre of angel investors and mentors in the early days that funded and brought those behind them along? What would Paris be without the bakers who let starving artists pay for bread with their paintings? What would hip-hop be without the radio DJs who would play these strange, new songs on air?

These small acts did not make history, but they are what made history. These gifts mattered.

Even though giving a sincere gift is difficult - demanding something of our souls -it’s what drives our culture forward.

Maximizing Organizational Performance: 7 Key Questions

Making organizations better is hard, but it doesn’t have to be complicated.

Leaders are often charged with "making the organization perform better." That's an incredibly difficult mission unless we understand what an organization, especially ours, is and how it works. Only then can we diagnose organizational problems and make improvements.

This is a pretty long, nerdy post, so here's the tl;dr for those in a hurry, and for those who need a little taste to prove the read is worth it.

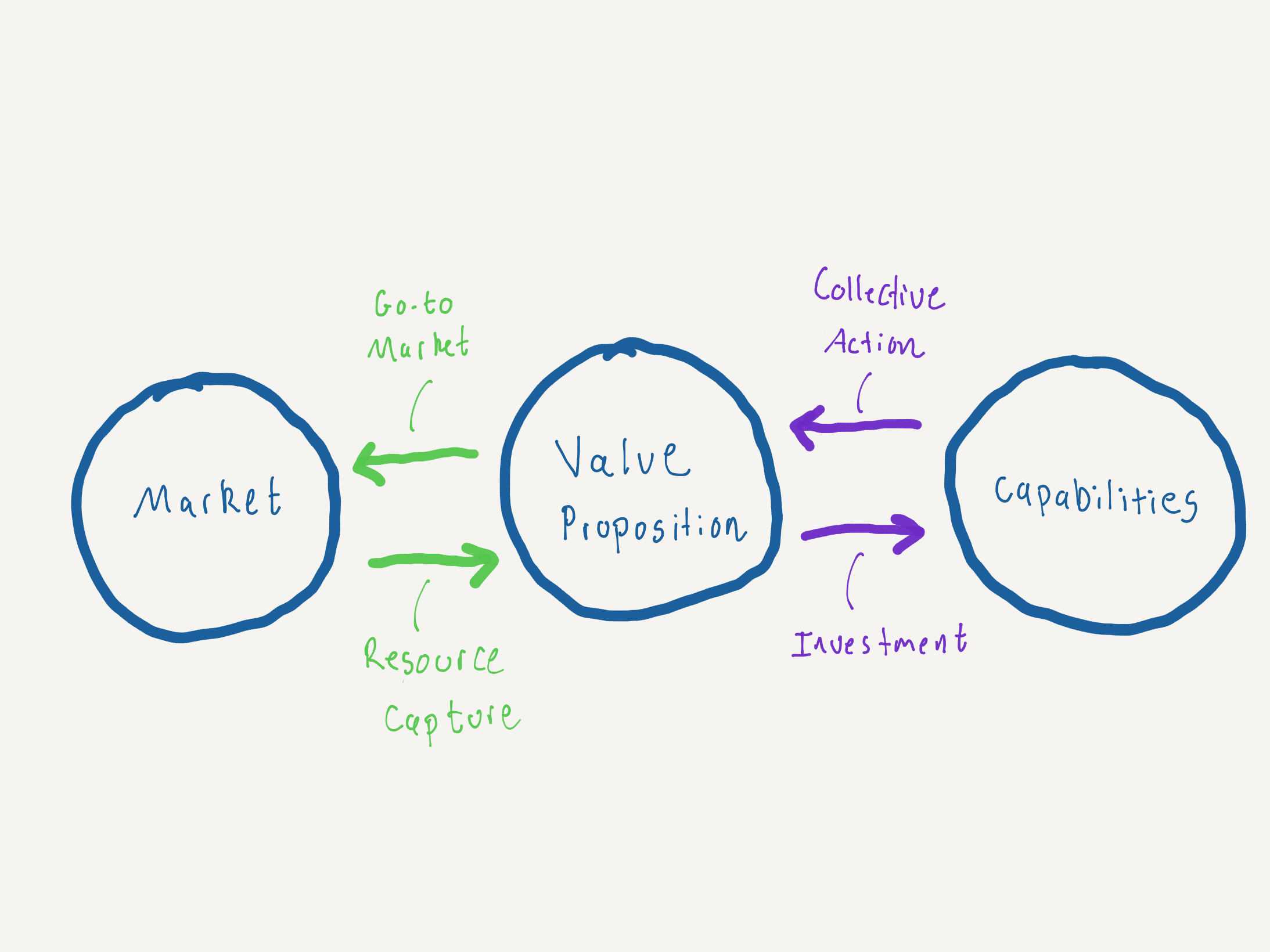

If you're trying to make an organization perform better, start by asking (just) seven questions. I think you'll make sense of your biggest problems pretty quickly:

Value Proposition: What do we create that other people are willing to sacrifice something (i.e., pay) for?

Market: Who cares about what we have to offer?

Capabilities: What are the handful of things we really need to be good at to create something of value?

Go-to-Market Systems: How will we engage with our market?

Resource Capture Systems: How does the organization get the resources it needs?

Collective Action Systems: How will we work together to turn our capabilities into something of value?

Investment Systems: How will we develop the capabilities that matter most?

Making organizations better is hard, but it doesn't have to be complicated.

Leaders are often charged to “make the organization perform better”. That’s an incredibly difficult mission unless we understand what an organizations, especially ours, is and how it works. Only then can we diagnose organizational problems and make improvements.

This is a pretty long, nerdy, post so here’s the tl;dr for those in a hurry, and for those that need a little taste to prove the read is worth it.

If you’re trying to make understand and organization and help it perform better, start with asking (just) seven questions. I think you’ll make sense of your biggest problems pretty quickly:

Value Proposition: What do we create that other people are willing to sacrifice something (i.e., pay) for?

Market: Who cares about what we have to offer?

Capabilities: What are the handful of things we really need to be good at to create something of value?

Go-to-Market Systems: How will we engage with our market?

Resource Capture Systems: How does the organization get the resources it needs?

Collective Action Systems: How will we work together to turn our capabilities into something of value?

Investment Systems: How will fwe develop the capabilities that matter most?

Making organizations better is hard, but it doesn’t have to be complicated.

The Seven-Part Model of Organizations

So, what is an organization?

I'd propose that an organization, at its simplest, is only made up of seven components:

Value Proposition

Market

Capabilities

Go-to-Market Systems

Resource Capture Systems

Collective Action Systems

Investment Systems

If we can understand these seven things about an organization, we can understand how it works and consequently make it perform better. There are certainly other models and frameworks for understanding organizations (e.g., McKinsey 7-S, Business Model Canvas, Afuah Business Model Innovation Framework) which serve specific purposes - and I do like those.

This seven-part model of organizations is the best I've been able to produce which maintains simplicity while still having broad explanatory power for any organization, not just businesses. Each component of the model answers an important question that an organization leader should understand.

The seven parts (Detail)

The first three parts of the model are what I think of as the outputs - they're the core foundation of what an organization is: a Value Proposition, a Market, and a set of Capabilities.

Value Proposition: What do we create that other people are willing to sacrifice something (i.e., pay) for?

The Value Proposition is the core of an organization. What do they produce or achieve? What is the good or the service? What makes them unique and different relative to other alternatives? This is the bedrock from which everything else can be understood. Why? Because the Value Prop is where the internal and external view of the organization come together - it's where the rubber meets the road.

It's worth noting that every stakeholder of the organization has to be satisfied by the Value Proposition if they are to engage with the organization: customers, constituents, shareholders, funders, donors, employees, suppliers, communities, etc.

Market: Who cares about what we have to offer?

Understanding the Market is also core to an organization because any organization needs to find product-market fit to survive. This question really has two subcomponents to understand: who the people are and what job they need to be done or need that they have that they're willing to sacrifice for.

It's not just businesses that need to clearly understand their Markets - governments, non-profits, and even families need to understand their Market. Why? Because no organization has unlimited resources, and if the Value Proposition doesn't match the Market the organization is trying to serve, the organization won't be able to convince the Market to part with resources that the organization needs to survive - whether that's sales, time, donations, tax revenues, or in the case of a family, love and attention from family members.

Capabilities: What are the handful of things we really need to be good at to create something of value?

Thus far, we've talked about what business nerd types call "product-market fit," which really takes the view that the way to understand an organization is to look at how it relates to its external environment.

But there's also another school of thought that believes a firm is best understood from the inside out - which is where Capabilities come in.

Capabilities are the stuff that the organization has or is able to do which they need to be able to produce their Value Proposition. These could be things like intellectual property or knowledge, skills, brand equity, technologies, or information.

Of course, not all Capabilities are created equal. When I talk about Capabilities, I'm probably closer to what the legendary CK Prahalad describes as "core competence." Let's assume our organization is a shoe manufacturer. Some of the most important Capabilities probably are things like designing shoes, recruiting brand ambassadors, and manufacturing and shipping cheaply.

The shoe company probably also has to do things like buy pens and pencils - so sure, buying office supplies is a Capability of the firm, but it's not a core Capability to its Value Proposition of producing shoes. When I say "Capabilities," I'm talking about the "core" stuff that's essential for delivering the Value Proposition.

Finally, we can think of how Capabilities interact with the Value Proposition as an analog to product-market fit, let's call it "product-capability fit." Aligning the organization with its external environment is just as important as aligning it to its internal environment.

When all three core outputs - Value Proposition, Market, and Capabilities - are in sync, that's when an organization can really perform and do something quite special.

In addition to the three core outputs, Organizations also have systems to actually do things. These are the last four components of the model. I think of it like the four things that make up an organization's "operating system."

Go-to-Market Systems: How will we engage with our Market?

How an organization "goes to market" is a core part of how an organization operates. Because after all, if the product or service never meets the Market, no value can ever be exchanged. The Market never gets the value it needs, and the organization never gets the resources it needs. A good framework for this is the classic marketing framework called the 4Ps: Price, Product, Place, and Promotion.

But this part of the organization's "operating system" need not be derived from private sector practice. Governments, nonprofits, faith-based organizations, and others all have a system for engaging with their Market; they might just call it something like "service delivery model," "logic model," "engagement model," or something else similar.

The key to remember here is that go-to-market systems are not how parties within the organization work together; it's how the organization engages with its Market.

Resource Capture Systems: How will the organization get the resources it needs?

Just like a plant or an animal, organizations need resources to survive. But instead of things like food, sunlight, water, and oxygen, and carbon dioxide, organizations need things like money, materials, talent, user feedback, information, attention, and more.

So if you're an organizational leader, it's critical to understand what resources the organization needs most, and having a solid plan to get them. Maybe it's a sales process or levying of a tax. Maybe it's donations and fundraising. Maybe for resources like talent, it's employer branding or a culture that makes people want to work for the organization.

This list of examples isn't meant to be comprehensive, of course. The point is that organizations need lots of resources (not just money) and should have a solid plan for securing the most important resources they need.