The Leadership Trifecta: Management, Leadership, Authorship

What matters is the nuance, because the three affect dynamics at different levels of organization: management affects individual dynamics, leadership affects team dynamics, and authorship affects ecosystem dynamics.

When we choose to lead, the first question we must answer is: who are we leading for?

Are we choosing to lead to enrich ourselves or everyone? Are we doing this for higher pay, social status, career advancement, and spoils? Or, are we doing this to improve welfare for everyone, enhance freedom and inclusion, or better the community?

If you're not in it for everyone (including yourself, but not exclusively or above others), you might as well stop reading. I am not your guy - there are plenty of others who have better ideas about power, career advancement, or gaining increased social status.

But if you're in it for everyone, if you're willing to take the difficult path to do the right thing for everyone in the right way, you probably struggle with the same questions I do, including this big one: what does choosing to lead even entail? Do I need to lead or manage? What am I even trying to do?

Is the goal management or leadership?

For many years, I’ve rolled my eyes whenever someone starts talking about leadership versus management or how we need people to transcend from being “managers” and elevate their game to become “leaders.” In my head, I'd question anytime this leadership vs. management paradigm comes up: “what are we even talking about?”

After many years, I finally have a point of view on this tired dialogue: management, leadership, and authorship all matter. What matters is the nuance, because the three affect dynamics at different levels of organization: management affects individual dynamics, leadership affects team dynamics, and authorship affects ecosystem dynamics.

Management, Leadership, and Authorship

Management, though the term itself is not what matters, can be defined as the practice of influencing individual performance. Think "1 on 1" when considering management. In management mode, the goal is to ensure that every individual is contributing their utmost.

Management primarily influences individual dynamics. Hence, when discussing management, we often refer to directing work, coaching, providing feedback, and developing talent. These are the elements that shape individual performance.

Similarly, leadership can be viewed as the practice of enhancing team performance as a collective unit. Think "the sum is greater than its parts" when contemplating leadership. In leadership mode, the goal is to ensure the team can make the highest possible contribution as a single unit.

Leadership predominantly affects team dynamics, which is why discussions about leadership often involve vision, strategy, culture, and processes. These elements impact the performance of a team functioning as a single unit.

Authorship, however, is the practice of influencing the performance of an entire network of teams and organizations aiming to achieve collective impact, often without formal or centralized coordination.

Authorship has become more feasible in recent history due to the rise of the internet. Unlike 50 years ago, many of us now have the opportunity to consider authorship because we can communicate with entire networks of people.

When considering authorship, think of it as being part of a movement that's larger than ourselves. In authorship mode, the goal is to mobilize an entire network to benefit an entire ecosystem - whether it's an industry, a community, a specific social issue or constituency, or in some cases, society as a whole. The aim is to ensure that the entire network is making the highest possible positive contribution to its focused ecosystem.

Authorship primarily affects ecosystem dynamics. That's why, when I ponder authorship, I think about concepts like purpose, narratives, opportunity structures, platforms, and shaping strategies. These elements influence entire networks and mobilize them to create a collective impact, particularly when they're not part of the same formal organization.

To illustrate, consider a software development company. In the context of management, the team lead may ensure every developer is performing at their best by providing guidance, setting clear expectations, and offering constructive feedback.

When it comes to leadership, the same team lead would be responsible for setting the vision for their team, aligning it with the company's goals, creating a positive team culture, and facilitating effective communication.

Authorship, however, would usually (but not necessarily) involve the CEO or top management. They would work towards building industry partnerships, contributing to open-source projects, or organizing industry conferences, ultimately aiming to influence the broader tech ecosystem, perhaps to achieve a broader aim like improving growth in their industry or solving a social problem - like privacy or social cohesion - through technology.

It all boils down to three questions:

Management question: On a scale of 1 to 100 how much of my potential to make a positive impact am I actually making?

Leadership question: On a scale of 1 to 100, how much of our team’s potential to make a positive impact are we actually making?

Authorship question: On a scale of 1 to 100, how much of our potential positive impact are we making, together with our partners, on our ecosystem or the broader world?

To assess your potential impact on a scale from 1 to 100, start by understanding the maximum positive impact you, your team, or your ecosystem could theoretically achieve. This '100' could be based on benchmarks, best practices, or even ambitious goals. Then, honestly evaluate how close you are to that maximum potential. This is not a perfect science and will require introspection, feedback, and perhaps even some experimentation. The important thing is to have a reference point that helps you understand where you are and where you could go.

In my own practice of leading, these are the questions I have been starting to ask myself and others. These three questions are incredibly helpful and revealing if answered honestly.

To really make a positive impact, I’ve found that it’s important to ensure all three dynamics - individual, team, and ecosystem - are examined honestly. If we truly are doing this to benefit everyone (ourselves included) we need to be good at management, leadership, and authorship.

Developing skills in these three areas isn't always straightforward, but you can start small. The easiest way I know of is to begin asking these three questions. If you’re in a 1-on-1 meeting or even conducting your own self-reflection, ask the management question. If you’re in a weekly team meeting, ask the leadership question. If you’re meeting with a larger team or a key partner, ask the ecosystem question.

Beginning with honest feedback initiates a continuous improvement engine that leads to enhancement in our capabilities of management, leadership, and authorship.

In conclusion, whether we're discussing management, leadership, or authorship, it's clear that each plays a crucial role in achieving positive impact. From enhancing individual performance to influencing entire ecosystems, each area has its distinct but interrelated role. As leaders, our challenge and opportunity lie in understanding these nuances and developing our capabilities in all three areas. Remember, it's not about choosing between management, leadership, and authorship - it's about embracing all three to maximize our collective potential.

I'd love to hear your thoughts on these three aspects of leading - management, leadership, and authorship. How have you balanced these roles in your own leadership journey? What challenges have you faced? Feel free to share your experiences and insights in the comments below or reach out to me personally.

Photo by Aksham Abdul Gadhir on Unsplash

The silhouette of brotherhood

I’m witnessing a brotherhood form. This is my deepest joy as a father.

It is so obvious how quickly children change. Even a single day after they are born, something changes. They learn and grow immediately. They start to eat, and they quickly discover how to grasp, with their whole hand, the little finger of their father.

Then they smile, sit up, and then crawl and walk. They speak and laugh. They get haircuts and pairs of new light-up velcro shoes and they learn to hold their breath while swimming.

They were born to change, truly. And it does happen fast. But occasionally we’ll notice something, one little thing, that endures a bit. One little, essential, thing about these children that will remain permanent even as they grow, like a thumbprint of their personality.

Something, finally, which is consistent and deeply comforting and helps us find a peaceful, amicable reconciliation with the passing time. I need these little, essential things to stay anchored when the water in our lives gets choppy.

We are at the beach and I am sitting in the sand when Robert catches my eye.

He is about 25 yards ahead of me, at the water’s edge. As he looks out at the the waves I notice his silhouette, the tide splashing past his ankles. I am awestruck by how Robert’s posture and demeanor have remained consistent over the years.

Robert has an empathy and quiet confidence in his posture. His feet are grounded and his back is straight, but there’s a softness to his stance. He stands like an explorer does who has both the anticipation to go where others have not and the humility to appreciate the vastness of the ocean before him. Robert’s silhouette has had a tender graciousness to it his whole life.

Myles is about 10 feet ahead of me and is sitting cross-legged, while building sandcastles with his Grandad. I notice, immediately, the sturdiness in Myles’s back. His posture is upright, erect. His silhouette is eager, bold, and focused. His muscles and frame are sinewy and taut, and he always carries his chest a few degrees forward as if in an athlete’s ready stance.

And yet, just as everything about him is sturdy, Myles also radiates a sense of playfulness and joy - his body moves with a rhythm of jazz music even now, as he plops sand in the bucket shovel by shovel. This mix of intensity and ease gives him an uncommon swagger, I think to myself, which could not possibly have been taught to him - it’s something calm and natural. Myles’s silhouette has always been deliberate and electric, just as it is now, as I watch him fill another bucket with wet sand.

And finally, I turn my gaze to Emmett, who has just crawled out from between my legs to be closer to the action of the sandcastle factory in front of me. Even at just one year old, Emmett’s unique qualities are already starting to emerge. Emmett’s posture is open and gregarious. His arms and his legs, even while sitting on the beach, are spread out as if he’s giving the breeze and the sunshine a hug as he giggles.

Emmett’s silhouette is like a starfish, always reaching and spreading his limbs and fingers to wave at, greet, and smile outwardly to the whole world. Already, I can tell that within Emmett there is an enduring openness, friendliness, and dynamic warmth. This is a truth his silhouette is already revealing.

These are the silhouettes of my three sons. What I am seeing is my three sons. And even though so much of who they are and who they will be is not yet decided, I am seeing something essential about them. There is something of them that is already drawn. Something that will not change. And what is already drawn is something unique and something good.

And then I snap back to the moment. The children laughing, the friends, the sand, the waves, and the horizon all come back into focus. I’m back here, sitting on the beach.

But then I remember some of the other wonderful silohouttes I’ve seen throughout this day at the beach and this trip - like when Myles and Robert were walking hand in hand down the boardwalk, or when the three of them were dog-piling on the floor laughing and tickling each other, or when they were all right in front me me working on the same sandcastle.

What I’m seeing is a bond being formed. As I watch my three sons play and explore the world together, their individual silhouettes are blending together to form a beautiful, harmonious picture of brotherhood. Witnessing this is what fills my heart the most.

There have been so many moments during this trip where I see them together, the lines of their silhouettes and complementary postures all within one frame. What gives me the deepest pleasure as a father is seeing the Tambe Brothers become a silhouette of it’s own.

And deep down, I accept their relationship with each other will grow and evolve. They’ll tussle and wrastle and have spats from time to time. I know this.

I know that their bond as brothers will never again be the same as it is now. Time will, despite my best efforts and sincerest prayers, continue to pass.

But I know, too, that something about this scene in front of me won’t change. Something of their brotherhood is already drawn and will endure, even after we are gone. I find comfort in this. This is the anchor I am looking for.

This image of the three of them together, in a bond of harmonious brotherhood, is the silhouette I treasure the most.

Photo by Pichara Bann on Unsplash

Reverse-Engineering Life's Meaning

Finding meaning is an act of noticing.

It's difficult to directly answer questions like "why am I here," "what is the meaning of my life," or "what's my purpose." It may even be impossible.

However, I believe we can attempt to reverse-engineer our sense of meaning or perhaps trick ourselves into revealing what we find meaningful. Here's how I've been approaching it lately.

Meaning, it seems, is an exercise in making sense of the world around us and, by extension, our place in it.

Instead of tackling the big question head-on (i.e., what's the meaning of my life), we can examine what we find salient and relevant about the world around us and work backward to determine what the "meaning" might be.

Here's what I mean. The italicized text below represents my inner monologue when contemplating the question, "What is the world out there outside of my mind and body? What is the world out there?"

The world out there is full of people, first and foremost. It teems with friends I haven't made yet, individuals with stories and unique contributions. Everyone has a talent and something special about them, I just know it. The world out there is full of untapped potential.

The world out there also contains uncharted territory. There is natural beauty everywhere on this planet. It is so varied and colorful, with countless plants, animals, rocks, mountains, rivers, and landscapes. The world out there is wild. Beyond that, we don't even know the mysteries of our own oceans and planet, let alone our solar system or the rest of the universe. The world out there is a vast galaxy filled with natural beauty and wonder.

But the world out there has its share of senseless human suffering, often due to our own mistakes and the systems we strive to perfect. There is rampant gun violence, hunger, homelessness, anger, and disease—all preventable. The world out there is a mess, but the silver lining is that not all of that senseless suffering is outside our control. We can make it better if we do better.

The world out there also has an abundance of goodness. Many people strive to be part of something greater than themselves. They help their neighbors, practice kindness, teach children to play the piano, visit the homebound, tell the truth, do the right thing, seek to understand other cultures, learn new languages, and strive to be respectful and inclusive. The world out there is full of parks, festivals, parties, and places where people play, eat, and share together. The world out there is generous.

The world out there is also close. My world is people like Robyn, Riley, Robert, Myles, and Emmett, as well as our parents, siblings, family, friends, colleagues, neighbors, and kind strangers. The world out there is our neighborhood, our backyard, our church, our school, and our local pub. It's the people on our Christmas card list and those we encounter around town for friendly conversations. The world out there includes the individuals I pray for during one or two rounds of a rosary. It doesn't have to be big and grand; it's the people I can hug, kiss, cook a meal for, or call just to say "hey."

So, the exercise is simple:

Find a place to write (pen, paper, computer, etc.).

Set a 15-minute timer.

Start with the phrase "The world out there is..." and keep writing. If you get stuck, begin a new paragraph with "The world out there is..." and continue.

After completing this exercise and taking stock of my own answers, I begin to see patterns in my responses that resonate with my day-to-day life. Meaning, for me, involves helping unleash the untapped potential in others, exploring the natural world, dreaming about the universe, fostering goodness and virtue, and being a person of good character. Meaning, for me, also entails honoring and cherishing my closest relationships, both the ones that are close in proximity and deep in their intimacy.

It seems that meaning is not generated in what we think of as our "brain." Our brain manages our body's energy budget, makes decisions, predicts the future, and solves problems. That’s our brain’s work.

Meaning, I believe, is created in our mind. When I think of the mind, I envision it as the function we perform when we absorb the seemingly infinite information about the external world through all five senses and attempt to make sense of it.

Meaning, it appears, is not an abstract thing we have to create. We don't "make" meaning. Instead, we discern meaning from what we find relevant and salient in the world around us. Out of the countless details about the external world, we hone in on certain aspects. The meaning is what bubbles to the top of our minds. We don't have to make meaning; we can just notice it.

This exercise has shown me that we can reverse-engineer our way into discovering meaning. If we can bring to the surface what we believe about the external world, it becomes clear what holds significance for us.

For example, if you find that "the world is full of cities and people, which leads to innovations in business, art, and culture," it's an easy leap to conclude that part of your meaning or purpose likely involves experiencing or improving cities and their cultural engines. If you discover that "the world is full of teachings about God and has a history of religious worship," it's a straightforward leap to deduce that part of your meaning or purpose likely relates to your faith and religious practice.

Being mindful of what we notice about the world is our back door into these abstract and challenging questions about "meaning" or "purpose."

What's difficult about this, I think, is the sheer volume of noise out there. Also, if we accept this perspective on meaning, we must acknowledge that meaning is not static and enduring—if it's discerned by our worldview, then changes in our perspective may also change or even manipulate our notions of meaning.

Many people try to tell us about the world outside of us. This includes companies through their commercials, authors, politicians, artists, philosophers, scientists, and priests—anyone who shares an opinion. Even I do this—if you're reading this, I am also guilty of adding to the noise that shapes your perspective of the external world.

Making sense of our lives is crucial for feeling sane and alive. It would be easy to average out what others around us say about the world out there, but if meaning truly is a discernment of what we notice about the external world, just listening to everyone else would effectively outsource the meaning in our lives to other people.

I don't think we should do that. After all, we live in a country where we have the freedom to speak, think, and make sense of the world for ourselves—what a terrible freedom to waste. Instead, we should be selective about who we pay attention to and listen to our own minds, noticing what they're trying to tell us. We shouldn't outsource meaning; we should notice it for ourselves.

Photo by Dawid Zawiła on Unsplash

Gifts drive culture

Culture often changes with extremely small, risky acts.

Robyn and I, technically, had two weddings. The first, on a Saturday, was celebrated by a priest in an old Catholic Church in Detroit. The church had hand-painted ceilings and huge multi-story pillars made of upper-peninsula timber, wider in diameter than hula hoops. It was beautiful.

The second ceremony was performed by a Hindu pandit, the next day. Shastri Ji is someone I’ve known since the age of 6, when we moved to Metro Detroit and started going to the local Temple. As he performed the Pheras, our marriage rites where we circled an open fire used for the ceremony, he shared two pieces of sage wisdom. I think about regularly.

First, he explained the essence of marriage, simply and with just one word - together, together, together.

Second, he shared an important idea in the Hindu conception of marriage, which explains one reason (among many) of why women are so important. A woman marrying into a family purifies it, not once, but twice - first she purifies her husband, second she purifies the ancestral line through any children she bears.

Marriage, in the way, is an act of double purification.

—

Even though giving a gift, truly and sincerely is difficult - demanding something of our souls - it’s what drives our culture forward.

It seems to me that there are two general ways to improve culture: changing possibilities and changing norms.

Changing possibilities requires an innovation, a new and better way of doing something. In this way refrigerators and democracy are quite similar.

Refrigerators gave a new and better of storing and preserving food, opening up the possibilities of agricultural exports, stretching the reach of the food supply, and culinary exploration for home cooks. Democracy gave a new and better way of governing states, opening up possibilities to mitigate the risk of tyrants and creating the condition of human rights and flourishing.

Changing norms requires a deviant behavior, ideally positive, which by definition is a risky act because it is different. In this way, art and telling someone you love them are quite similar.

Art is a risky act because the artist is bring a point of view, something fresh, that is untested and unusual, which means nobody may like, pay for, or even understand it. Telling someone you love them, obviously, is a risk because if they don’t say it back it’s surely heartbreaking.

The risk is what makes positive deviance so impactful - the deviant bears the social risk of being different, proves that different is possible. This is how norms change.

Innovations have switching costs, which is what makes them feel so sudden, so violent sometimes. Pressure builds, like a tea kettle, and then when the time has come for the better way, it bursts and whistles, jolting the masses into something novel. The nature of culture changing innovations is that of a phase shift.

Gifts can be gradual. They change the culture one conversation and one hug at a time. The effects of gifts layer, and years later we wonder, “how could it have ever been different?”

So many of the littlest moments can be gifts, like when we hear…

“Excuse ma’am, you dropped this,” in the grocery line.

“Good afternoon,” as a neighbor smiles as we pass on the sidewalk.

“Thank you for your leadership,” from a respected colleague.

“I know you like this kind of granola,” from our spouse who went grocery shopping.

“Let me get that for you,” from a shopkeeper who sees our hands are full.

Or “I’m glad you’re here,” from just about anyone at any time.

—

There is a certain agony that comes from buying a present that’s really from the heart. In a moment of Charlie Brown-esque inner turmoil, we think, “dear God, I hope they like it.”

Part of this angst is about the gift itself. There’s a genuine worry that the contents of the package will be pleasing to the person whose day we seek to brighten.

The other half of the angst is that the TLC we put into the gift will be rejected, or wasted. We worry about the risk we have taken, the love that we have wagered in this gift, and whether that piece of our soul that we’ve woven into the wrapping and bow will be seen, or if it will not.

It seems to me that this is what all gifts have in common, even if that gift is simply holding the door open for the stranger in public who happens to also be walking into the Olive Garden for an early dinner.

All gifts are both the content of the gift, plus the social risk taken to give it. When we give a gift that is truly sincere, we acknowledge that our effort may be shunned and proceed anyway.

I think that’s what makes a gift truly special. Perhaps it’s not quite the thought that counts, but the risk that counts even more. We intuitively understand this - we respond emotionally and perhaps unconsciously to the notion that “someone bore all this risk, for me?”

And so too for the giver, they also respond emotionally and perhaps unconsciously to the notion that “I was able to shoulder all this risk, for someone else?”

Gifts, too, are an act of double purification.

—-

I am fascinated by Silicon Valley, the salons of Europe, or even Detroit and New York when Motown and hip-hop were coming on the scene in the back half of the 20th century. How did these creative clusters develop? How did it happen? How did these incredibly vibrant, artistic, and entrepreneurial places emerge?

In Detroit, to be called an “OG”, short for “Original Gangster” is one of the highest signs of respect one can be bestowed with. It doesn’t simply mean, “old person”, it implies some level of experience but also generosity. An OG is someone who not only has the wisdom of experience but the willingness to be a pillar of a community, that others can lean on to grow and thrive.

Being on OG implies that you were not only successful in your own right, but were also responsible for helping the next generation come up behind you.

I think it’s these OGs, who are often working behind the scenes in a community, that are the unsung heroes of these creative cluster. What would Silicon Valley be without the cadre of angel investors and mentors in the early days that funded and brought those behind them along? What would Paris be without the bakers who let starving artists pay for bread with their paintings? What would hip-hop be without the radio DJs who would play these strange, new songs on air?

These small acts did not make history, but they are what made history. These gifts mattered.

Even though giving a sincere gift is difficult - demanding something of our souls -it’s what drives our culture forward.

Maximizing Organizational Performance: 7 Key Questions

Making organizations better is hard, but it doesn’t have to be complicated.

Leaders are often charged with "making the organization perform better." That's an incredibly difficult mission unless we understand what an organization, especially ours, is and how it works. Only then can we diagnose organizational problems and make improvements.

This is a pretty long, nerdy post, so here's the tl;dr for those in a hurry, and for those who need a little taste to prove the read is worth it.

If you're trying to make an organization perform better, start by asking (just) seven questions. I think you'll make sense of your biggest problems pretty quickly:

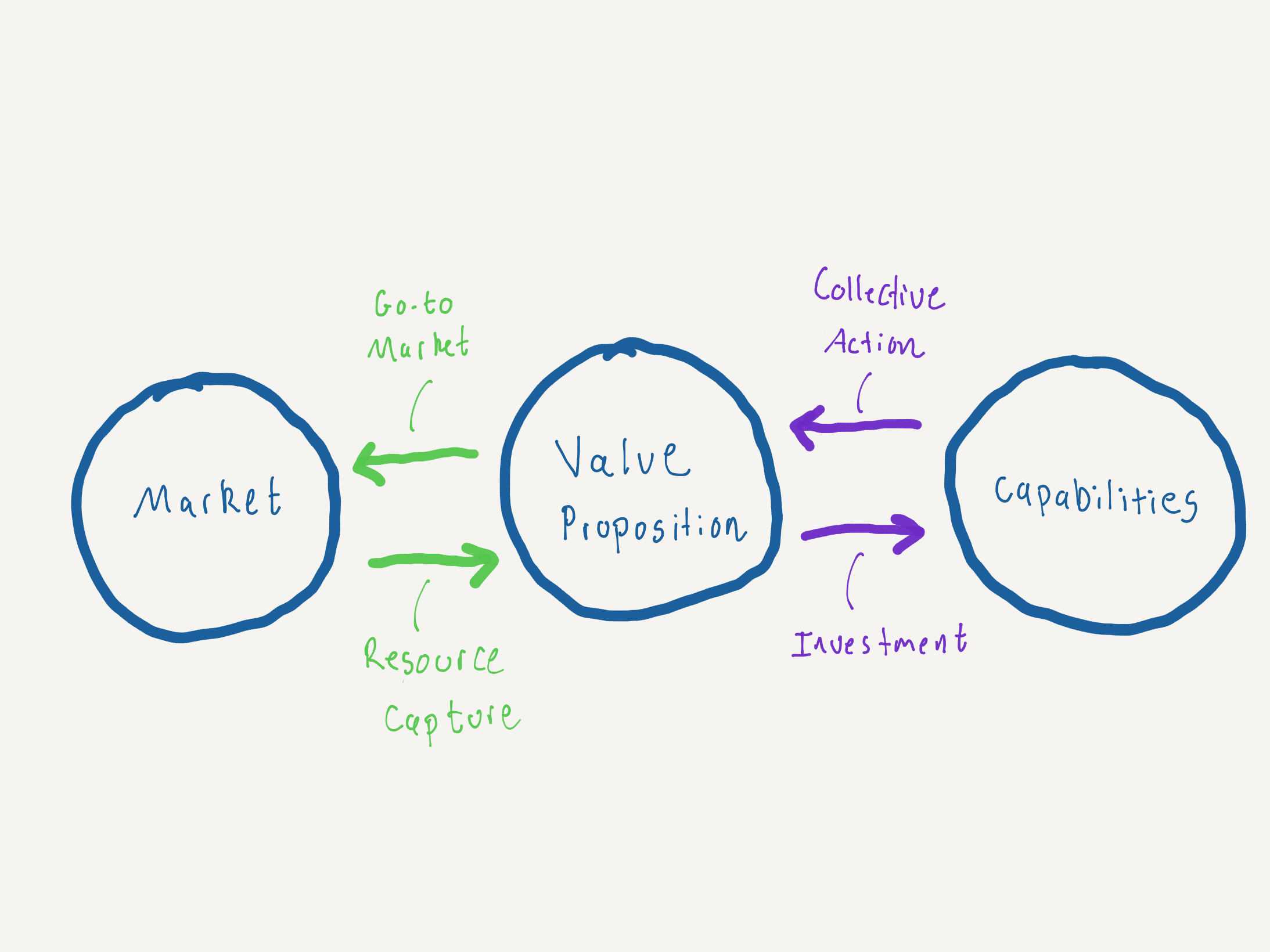

Value Proposition: What do we create that other people are willing to sacrifice something (i.e., pay) for?

Market: Who cares about what we have to offer?

Capabilities: What are the handful of things we really need to be good at to create something of value?

Go-to-Market Systems: How will we engage with our market?

Resource Capture Systems: How does the organization get the resources it needs?

Collective Action Systems: How will we work together to turn our capabilities into something of value?

Investment Systems: How will we develop the capabilities that matter most?

Making organizations better is hard, but it doesn't have to be complicated.

Leaders are often charged to “make the organization perform better”. That’s an incredibly difficult mission unless we understand what an organizations, especially ours, is and how it works. Only then can we diagnose organizational problems and make improvements.

This is a pretty long, nerdy, post so here’s the tl;dr for those in a hurry, and for those that need a little taste to prove the read is worth it.

If you’re trying to make understand and organization and help it perform better, start with asking (just) seven questions. I think you’ll make sense of your biggest problems pretty quickly:

Value Proposition: What do we create that other people are willing to sacrifice something (i.e., pay) for?

Market: Who cares about what we have to offer?

Capabilities: What are the handful of things we really need to be good at to create something of value?

Go-to-Market Systems: How will we engage with our market?

Resource Capture Systems: How does the organization get the resources it needs?

Collective Action Systems: How will we work together to turn our capabilities into something of value?

Investment Systems: How will fwe develop the capabilities that matter most?

Making organizations better is hard, but it doesn’t have to be complicated.

The Seven-Part Model of Organizations

So, what is an organization?

I'd propose that an organization, at its simplest, is only made up of seven components:

Value Proposition

Market

Capabilities

Go-to-Market Systems

Resource Capture Systems

Collective Action Systems

Investment Systems

If we can understand these seven things about an organization, we can understand how it works and consequently make it perform better. There are certainly other models and frameworks for understanding organizations (e.g., McKinsey 7-S, Business Model Canvas, Afuah Business Model Innovation Framework) which serve specific purposes - and I do like those.

This seven-part model of organizations is the best I've been able to produce which maintains simplicity while still having broad explanatory power for any organization, not just businesses. Each component of the model answers an important question that an organization leader should understand.

The seven parts (Detail)

The first three parts of the model are what I think of as the outputs - they're the core foundation of what an organization is: a Value Proposition, a Market, and a set of Capabilities.

Value Proposition: What do we create that other people are willing to sacrifice something (i.e., pay) for?

The Value Proposition is the core of an organization. What do they produce or achieve? What is the good or the service? What makes them unique and different relative to other alternatives? This is the bedrock from which everything else can be understood. Why? Because the Value Prop is where the internal and external view of the organization come together - it's where the rubber meets the road.

It's worth noting that every stakeholder of the organization has to be satisfied by the Value Proposition if they are to engage with the organization: customers, constituents, shareholders, funders, donors, employees, suppliers, communities, etc.

Market: Who cares about what we have to offer?

Understanding the Market is also core to an organization because any organization needs to find product-market fit to survive. This question really has two subcomponents to understand: who the people are and what job they need to be done or need that they have that they're willing to sacrifice for.

It's not just businesses that need to clearly understand their Markets - governments, non-profits, and even families need to understand their Market. Why? Because no organization has unlimited resources, and if the Value Proposition doesn't match the Market the organization is trying to serve, the organization won't be able to convince the Market to part with resources that the organization needs to survive - whether that's sales, time, donations, tax revenues, or in the case of a family, love and attention from family members.

Capabilities: What are the handful of things we really need to be good at to create something of value?

Thus far, we've talked about what business nerd types call "product-market fit," which really takes the view that the way to understand an organization is to look at how it relates to its external environment.

But there's also another school of thought that believes a firm is best understood from the inside out - which is where Capabilities come in.

Capabilities are the stuff that the organization has or is able to do which they need to be able to produce their Value Proposition. These could be things like intellectual property or knowledge, skills, brand equity, technologies, or information.

Of course, not all Capabilities are created equal. When I talk about Capabilities, I'm probably closer to what the legendary CK Prahalad describes as "core competence." Let's assume our organization is a shoe manufacturer. Some of the most important Capabilities probably are things like designing shoes, recruiting brand ambassadors, and manufacturing and shipping cheaply.

The shoe company probably also has to do things like buy pens and pencils - so sure, buying office supplies is a Capability of the firm, but it's not a core Capability to its Value Proposition of producing shoes. When I say "Capabilities," I'm talking about the "core" stuff that's essential for delivering the Value Proposition.

Finally, we can think of how Capabilities interact with the Value Proposition as an analog to product-market fit, let's call it "product-capability fit." Aligning the organization with its external environment is just as important as aligning it to its internal environment.

When all three core outputs - Value Proposition, Market, and Capabilities - are in sync, that's when an organization can really perform and do something quite special.

In addition to the three core outputs, Organizations also have systems to actually do things. These are the last four components of the model. I think of it like the four things that make up an organization's "operating system."

Go-to-Market Systems: How will we engage with our Market?

How an organization "goes to market" is a core part of how an organization operates. Because after all, if the product or service never meets the Market, no value can ever be exchanged. The Market never gets the value it needs, and the organization never gets the resources it needs. A good framework for this is the classic marketing framework called the 4Ps: Price, Product, Place, and Promotion.

But this part of the organization's "operating system" need not be derived from private sector practice. Governments, nonprofits, faith-based organizations, and others all have a system for engaging with their Market; they might just call it something like "service delivery model," "logic model," "engagement model," or something else similar.

The key to remember here is that go-to-market systems are not how parties within the organization work together; it's how the organization engages with its Market.

Resource Capture Systems: How will the organization get the resources it needs?

Just like a plant or an animal, organizations need resources to survive. But instead of things like food, sunlight, water, and oxygen, and carbon dioxide, organizations need things like money, materials, talent, user feedback, information, attention, and more.

So if you're an organizational leader, it's critical to understand what resources the organization needs most, and having a solid plan to get them. Maybe it's a sales process or levying of a tax. Maybe it's donations and fundraising. Maybe for resources like talent, it's employer branding or a culture that makes people want to work for the organization.

This list of examples isn't meant to be comprehensive, of course. The point is that organizations need lots of resources (not just money) and should have a solid plan for securing the most important resources they need.

Collective Action Systems: How will we work together to turn our capabilities into something of value?

Teamwork makes the dream work, right? I'd argue that's even an understatement. The third aspect of the organization's operating system is collective action.

This includes things like operations, organization structure, objective setting, project management approaches, and other common topics that fall into the realm of management, leadership, and "culture."

But I think it's more comprehensive than this - concepts like mission, purpose, and values, decision chartering, strategic communications, to name a few, are of growing importance and fall into the broad realm of collective action, too.

Why? Two reasons: 1) organizations need to move faster and therefore need people to make decisions without asking permission from their manager, and, 2) organizations increasingly have to work with an entire network of partners across many different platforms to produce their Value Proposition. These less-common aspects of an organization's collective action systems help especially with these challenges born of agility.

So all in all, it's essential to understand how an organization takes all its Capabilities and works as a collective to deliver its Value Proposition - and it's much deeper than just what's on an org chart or process map.

Investment Systems: How do we develop the capabilities that matter most?

It's obvious to say this, but the world changes. The Market changes. Expectations of talent change. Lots of things change, all the time. And as a result, our organizations need to adapt themselves to survive - again, just like Darwin's finches.

But what does that really mean? What it means more specifically is that over time the Capabilities an organization needs to deliver its Value Proposition to its Market changes over time. And as we all know, enhanced Capabilities don't grow on trees - it takes work and investment, of time, effort, money, and more.

That's where the final aspect of an organization's operating system comes in - the organization needs systems to figure out what Capabilities they need and then develop them. In a business, this could mean things like "capital allocation," "leadership development," "operations improvement," or "technology deployment."

But the need for Investment Systems applies broadly across the organizational world, too, not just companies.

As parents, for example, my wife and I realized that we needed to invest in our Capabilities to help our son, who was having a hard time with feelings and emotional control. We had never needed this "capability" before - our "market" had changed, and our Value Proposition as parents wasn't cutting it anymore.

So we read a ton of material from Dr. Becky and started working with a child and family-focused therapist. We put in the time and money to enhance our "capabilities" as a family organization - and it worked.

Again, because the world changes, all organizations need systems to invest in themselves to improve their capabilities.

My Pitch for Why This Matters

At the end of the day, most of us don't need or even want fancy frameworks. We want and need something that works.

I wanted to share this framework because this is what I'm starting to use as a practitioner - and it's helped me make sense of lots of organizations I've been involved with, from the company I work for to my family.

If you're someone - in any type of organization, large or small - I hope you find this very simple set of seven questions to help your organization perform better.

Making organizations better is hard, but it doesn't have to be complicated.

Holding onto forever

To be held is to be loved.

ACT I

I appreciate things I can hold. I mean this literally.

I savor burritos and breakfast sandwiches - these are the foods that I enjoyed with my father and remind me of him, down to the detail of us both dousing them with hot sauce. I relish the feel of a tennis racket in my grasp, gripped to perfectly that the racket feels like it’s gripping back - the tennis court was where I could find peace and freedom, before I even knew what meditation even was.

I like pens, pencils, and chef’s knives - because words and a meal prepared for others are two of the only ways I know how to tell someone I love them. All those three objects - pens, pencils, and a good knife - feel less like implements and more like extensions when I handle them. Then take on the rhythm and flow of my heartbeat and tapping toe, as if they’re a part of my body.

With the things I hold, I develop a symbiotic relationship. I fuse with them somehow - I become a little of them, and they become a little of me. This connection brings a feeling of peace, serenity, and security.

My whole life may resemble that one chaotic drawer in the house, filled with knick-knacks, rarely used items, and tiny screwdrivers that only see the light of day in a frenzy. But when I'm holding something in my hand, I've got it. And when I've got the thing in my hand, I start to feel like I've got this. The act of the body changes the act of the mind.

I, quite literally, cherish things I can hold. But I also mean this metaphorically. I appreciate buffer and the freedom it provides, borne from a lifetime of needing to feel control and security. I prefer to save rather than spend. To this day, I pack one more pair of underwear than the number of nights I'm traveling. I’ll pack a rain jacket even when it’s sunny. I like to be prepared. I like to hold onto extra.

I think I do this because I know what it feels like to lose. When I was young, money was tight. It was tight again when the recessions hit Michigan. Our brother, Nakul, was taken from us too soon, as was my father. In some ways, the seriousness with which I was raised makes me feel like the innocence of childhood slipped away prematurely.

When I hold things, I' feel like I’ve got them. And when I've got them, I can tell myself for a little while that nobody else can take them. Now, I finally have a world - my wife, my children, my family, good friends, my health, a livelihood, and a few dreams - that's worth holding onto.

And I'm going to hold them in the palm of my hand, gripping them tight enough so that nobody can ever take them away from me.

I intend to hold onto them forever.

ACT II

Everything feels like forever when you're a child.

Even a summer vacation, with all its bike rides and fireflies, seems endless. Middle and high school, infused with a sense of invincibility, appear as though they'll never run out. Every long car ride, every grocery queue, every football practice - every single thing is long.

Childhood is the part of our lives that feels like forever.

And for you three, so much of that forever is shaped by your mom and me. The golden, fuzzy forever you experience - your memories of childhood - isn't entirely up to you. Part of it is your responsibility, sure. But a lot of it is ours.

And so I wonder - what will you three, my sons, remember about what forever felt like?

I want you to remember being held because to be held is to be loved. I want you to recall that you were loved. I want you to feel loved. I want you to be loved, and I want to love you.

Holding onto someone and being held is not a small thing. It, in a very physical way, proves that we are bonded. It proves that we are together and committed to each other. It demonstrates, with certainty that I care about you because I am here. The Jesuits talk about finding God in all things, and I think embraces are an example of what they mean in this teaching. There is something divine about being held, because to be held is to be loved.

You will have memories of fun, laughter, and joy, of course. You will experience snow days and summer nights. You'll have spring flings and Friday night lights. You'll have moments with your toes in Burt Lake and in the backyard grass on Parkside, ice cream dribbling down your chins. You'll have all this. I promise you'll have all this.

But when I think about my own childhood, the only thing that endures enough to be more than a memory but a feeling, a deep-seated sensation, is love. Love is what endures.

Even a single moment of true, unconditional love is what carries you when you want to give up or when you feel like all you can do is surrender everything. Just one moment of love is enough to save us.

I want you to remember being held because being held is to be loved. So that no matter what, you have that. When you think of the part of your life that was forever, I want you to feel like holding onto it. I want you to feel like holding onto forever.

This is why I must hold you, all three of you, forever.

ACT III

Nothing feels like forever now that we're grown. We have a clock, and it's ticking. Tick tock, tick tock.

When we’re drinking wine after the kids go to bed, I often say that last weekend feels like "forever ago," but that's not really true. Our days are full. Our nights never seem long enough to rest. Our weeks and weekends are packed enough to trick me into thinking time is passing slowly.

I notice this the most in photographs now. We look different than we did not long ago. I see it in our hair and skin. Our postures. The settings in which those photos were taken.

Seven years have passed since my favorite photo of our wedding day was captured. It's the one on our mantle, the black and white image in the silvery frame, where we're on the river, and you're embracing me from behind, around my neck and shoulders, your mehendi-adorned hand visible. I'm smiling at you over my right shoulder, looking up at you, as if you're the sunshine. It reminded me of what forever can feel like.

We've aged seven years since then, and luckily it doesn't look like more. But it feels like it should have only been two, maybe three years since that photo by the river. Tick tock, tick tock.

We hug and hold each other often and spontaneously. We naturally find our way to an embrace. It could be in the kitchen while the pasta is boiling, or for a few minutes in bed after you've showered, and I'm still lying in my pajamas. You hold me, and I hold you.

These moments, where we're holding each other, don't stop the clock. The clock moves ahead. The alarm rings. But during those moments, when we're holding onto each other, we're reminded. It takes us back to that photo by the river, where I am smiling, and you look like sunshine, in the moment that reminds me of forever.

And sometimes, when we were there in those embraces that remind me of forever, I don’t want to leave. I want to stay there. I feel safe there, loved there. To be held, after all, is to be loved.

But at the same time, what would our lives be if we did not have the world around us, if we just kept it to us in that embrace, just you and me?

If we did not have our children or our families? Or if we didn’t have our friends and neighbors? Or even kind strangers? To embrace them we have to open up and expand our hearts from just us, to give more than we think we have. To hold onto them, we have to let go.

I have to remember sometimes, that not everyone is trying to take you all away from me. Not everyone is a threat to what we finally have. I can hold on while still letting go, at least for as long as it takes to share some of the love in our hearts with others.

This ability to hold on and let go first felt like a paradox, but I think now that it’s merely a leap of faith. It is okay to make this leap, I know this now, because we will always get back to holding each other. We will come back to an embrace of each other. And we will get back to this place that reminds me of forever.

Photo by Marcel Ardivan on Unsplash

Overcoming Ivy League rejection, finally

Overcoming the weight of Ivy League rejection, I discovered that the key to success and self-worth lies in embracing our own unique paths.

I was rejected by the Ivy League on three separate occasions. Twice while applying for undergraduate studies and once for grad school. The best I could manage was getting on the waitlist of one public policy school.

The Ivies were not my dream or my “league”, per se, but the league everyone, it seemed, wanted me to be in. Everyone around me implicitly signaled that Ivy League admission was the symbol of being elite and on a trajectory of success and respect. I don’t think I could've had an independent thought about the matter because the aura of the Ivy League was so insidious and pervasively woven into my psyche while I was growing up. Everyone else put their faith in the Ivy League, so I did too.

Ever since, it has been the source of whatever inferiority complex I have. I believe I am dumber than other people because I didn’t get into an Ivy League school. I thought I had to catch up, prove myself, and show everyone that I’m elite, too.

In a way, the Ivy League mythology is probably true. Extremely talented and capable people gain admission into Ivy League schools. And if I had too, I assume my career would’ve been easier and simpler. My “network” would have probably been more powerful and able to open stubborn doors. More people would’ve probably been knocking on my door, instead of the other way around.

And perhaps more importantly, I would’ve believed in myself more. It would’ve been a self-fulfilling cycle. If I had been admitted to the Ivy League, I would’ve believed that I was somebody. And because I believed that, I would’ve spent all that time I was insecure and engaging in negative self-talk actually being somebody. All the times I told myself stories about how I was too down-to-earth to go to the Ivy League, I could’ve been making a contribution.

The biggest trap of all this was not whether or not I got into an Ivy League school, but that I spent so much time in my life thinking about it, questioning what I was, and wondering what might’ve been. What a waste of time and energy.

What I realize now is that life and career are instances of product-market fit. Being able to make an impactful contribution is not just a matter of being talented but a matter of applying one's talents in the most impactful way. That is what I envy so much about Ivy Leaguers; nobody seems to tell them what they should do and what they should be. They seem like they have more mental freedom to just go in the direction they want, without too much questioning.

Even me, going to a relatively elite public university twice, people signal to me what I should be and what I should do all the time. They think they can fit me into the mold they want me to be. They think they can force me into their narrative. That’s what it feels like anyway.

Maybe none of this is true. Maybe nothing would’ve been different had I gotten into Harvard, Columbia, or any other Ivy League school. But putting this all on paper is proving to me that the mythology of the Ivy League has been in my head, rent-free, for a long time. I’ve been waiting for someone to validate my intellect, talent, and capability for so long.

—

The West Wing is probably my favorite television show of all time. I was turned onto it by Lee, who was one of my managers and role models when I was a consultant at Deloitte.

The funny part is that Lee was Canadian, and I figured if someone who wasn’t even born in the US was undeterred in his enthusiasm for a show dramatizing the American presidency, I would probably like it too.

One of my favorite moments of the show is the scene where the Chief of Staff, Leo McGarry, talks with the President and outlines a new strategy for the administration: “Let Bartlet be Bartlet.”

I think that's the lesson here: all of us need to find that moment when we find our footing. We should stop trying to be someone we're not. We need to accept that we should focus on being who we are, instead of obsessing over Ivy League admission, promotions, or awards.

I think we all need that moment when we realize we can embrace our individuality, whether it's "Let Tambe be Tambe," "Let Paul be Paul," "Let Detroit be Detroit," "Let Smith be Smith," or any other iteration that our identity requires.

This whole time, I've been depending on the Ivy League to give me permission to be myself. This whole time, I've been dangling my feet out, hoping for my choices to be validated by someone else.

The greatest lesson in all this has nothing to do with the Ivy League. The lesson here is that we need to create this moment where we grant ourselves permission to be ourselves.

In my case, the turning point came when a role model at work told me about his circuitous path and how he embraced it, reminding himself that sometimes "you've got to bet on yourself."

Maybe we can't will ourselves, completely on our own, to grant self-permission for self-authorship. It's okay and expected to need help, support, and encouragement. But I don't think we need an institution to "pick" us, either. I never needed the Ivy League to "Let Tambe be Tambe," though maybe that would've sped up the process. All I needed, and all that I think any of us need, is someone to remind us that the choice to grant ourselves permission is one that we're allowed to make.

The path is ours to walk if we're willing to claim it as our own.

The potential of Government CX to improve social trust

Government CX is a huge opportunity that we should pursue.

Several times last week, while traveling in India, people cut in front of my family in line. And not slyly or apologetically, but gratuitously and completely obliviously, as if no norms around queuing even exist.

In this way, India reminds me of New York City. There are oodles and oodles of people, that seem to all behave aggressively - trying to get their needs met, elbowing and jockey their way through if they need to. It’s exhausting and it frays my Midwestern nerves, but I must admit that it’s rational: it’s a dog eat dog world out there, so eat or be eaten.

What I realized this trip, is that even after a few days I found myself meshing into the culture. Contrary to other trips to India, I now have children to protect. After just days, I began to armor up, ready to elbow and jockey if needed. I felt like a different person, more like a “papa bear” than merely a “papa”. like a local perhaps.

I even growled a papa bear growl - very much unlike my normal disposition. Bo, our oldest, had to go to the bathroom on our flight home so I took him. We waited in line, patiently, for the two folks ahead of us to complete their business. Then as soon as we were up, a man who joined the line a few minutes after us just moved toward the bathroom as if we had never been there waiting ahead of him

Then the papa bear in me kicked in. This is what transpired in Hindi, translated below. My tone was definitely not warm and friendly:

Me: Sir, we were here first weren’t we?

Man: I have to go to the bathroom.

Me: [I gesture toward my son and give an exasperated look]. So does he.

And then I just shuffled Bo and I into the bathroom. Elbow dropped.

But this protective instinct came at a cost. Usually, in public, I’m observant of others, ready to smile, show courteousness, and navigate through space kindly and warmly. But all the energy and attention I spent armoring up, after just days in India, left me no mind-space to think about others.

This chap who tried to cut us in line, maybe he had a stomach problem. Maybe he had been waiting to venture to the lavatory until an elderly lady sitting next to him awoke from a nap. I have no idea, because I didn’t ask or even consider the fact that this man may have had good intentions - I just assumed he was trying to selfishly cut in line.

Reflecting on this throughout the rest of the 15 hour plane ride, it clicked that this toy example of social trust that took place in the queue of an airplane bathroom reflects a broader pattern of behavior. Social distrust can have a vicious cycle:

Someone acts aggressively toward me

I feel distrust in strangers and start to armor up so that I don’t get screwed and steamrolled in public interactions

I spend less time thinking about, listening to, and observing the needs of others around me

I act even more aggressively towards strangers in public interactions, because I’m thinking less about others

And now, I’ve ratcheted up the distrust, ever so slightly, but tangibly.

The natural response to this ratcheting of social distrust is to create more rules, regulations, and centralize power in institutions. The idea being, of course, that institutions can mediate day to day interactions between people so the ratcheting of social distrust has some guardrails put upon it. When social norms can’t regulate behavior, authority steps in.

The problem with institutional power, of course, is that it’s corruptible and undermines human agency and freedom. Ratcheting up institutional power has tradeoffs of its own.

—

Later during our journey home, we were waiting in another line. This time we were in a queue for processing at US Customs and Border patrol. This time, I witnessed something completely different.

A couple was coming through the line and they asked us:

Couple: Our connecting flight is boarding right now. I’m so sorry to ask this, but is it okay if we go ahead of you in line?

Us: Of course, we have much more time before our connecting flight boards. Go ahead.

Couple: [Proceeds ahead, and makes the same request to the party ahead of us].

Party ahead of us: Sorry, we’re in the same boat - our flight is boarding now. So we can’t let you cut ahead.

Couple: Okay, we totally understand.

The first interaction in line at the airplane bathroom made me feel like everyone out there was unreasonable and selfish. It undermined the trust I had in strangers.

This interaction in the customs line had the opposite effect, it left me hopeful and more trusting in strangers because everyone involved behaved considerately and reasonably.

First, the couple acknowledged the existence of a social norm and were sincerely sorry for asking us to cut the line. We were happy to break the norm since we were unaffected by a delay of an extra three minutes. And finally, when the couple ahead said no, they abided by the norm.

We were all observing, listening, and trying to help each other the best we could. In my head, I was relieved and I thought, “thank goodness not everyone’s an a**hole.

It seems to me that just as there’s a cycle that perpetuates distrust, there is also a cycle which perpetuates trust:

Listen and seek to understand others around you

Do something kind that helps them out without being self-destructive of your own needs

The person you were kind toward feels higher trust in strangers because of your kindness

The person you were kind to can now armor down ever so slightly and can listen for and observe the needs of others

And now, instead of a ratchet of distrust, we have a ratchet of more trust. Instead of being exhausting like distrust, this increase in trust is relieving and energy creating.

—

At the end of the day, I want to live in a free and trusting society. If there was to be one metric that I’m trying to bend the trajectory on in my vocational life - it’s trust. I want to live in a world that’s more trusting.

This desire to increase trust in society is why I care so much about applying customer experience practices to Government. Government can disrupt the cycle of distrust and start the flywheel of trust in a big way - and not just between citizens and government but across broader culture and society.

Imagine this: a government agency, say the National Parks Service, listens to its constituents and redesigns its digital experience. Now more and more people feel excited about visiting a National Park and are more able to easily book reservations and be prepared for a great trip into one of our nation’s natural treasures.

So now, park visitors have more trust in the National Park Service going into their trip and are more receptive to safety alerts and preservation requests from Park Rangers. This leads to a better trip for the visitor, a better ability for Rangers to maintain the park, and a higher likelihood of referral by visitors who have a great trip. This generates new visitors and adds momentum to the flywheel.

I’m a dataset of one, but this is exactly what happened for me and my family when we’ve interacted with the National Parks’ Service new digital experience. And there’s even some data from Bill Eggers and Deloitte that is consistent with this anecdote: CX is a strong predictor of citizens’ trust in government.

And now imagine if this sort of flywheel of trust took place across every single interaction we had with local, state, and federal government. Imagine the mental load, tension, and exhaustion that would be averted and the positive affect that might replace it.

It could be truly transformational, not just with what we believe about government, but what we believe about the trustworthiness of other citizens we interact with in public settings. If we believe our democratic government - by the people and for the people - is trustworthy, that will likely help us believe that “the people” themselves are also more trustworthy. After all, Government does shape more of our. daily interactions than probably any other institution, but Government also has an outsized role in mediating our interactions with others.

Government CX is a huge opportunity that we should pursue, not only because of the improvement to delivery of government service or the improvement of trust in government. Improvement to government CX at the local, state, and federal levels could also have spillover effects which increase social trust overall. No institution has the reach and intimate relationship with people to start the flywheel of trust like customer-centric government could, at least that I can see.

Photo by George Stackpole on Unsplash

Light only spreads exponentially

The algorithm is simple: Light, spread, teach others to spread.

We start with nothing.

And that in a way gives us a beginning. Nothing is from where we all start.

What we need first then, to spread light, is a candle. We need substance. We need our bodies. We need education. We need love. We need food, a home, and a place to work. We need all these things, which are a vessel to sustain light. For some, this candle is a birthright or a gift. Some of us must make our own.

Next, we light the candle. We figure out something which illuminates. We do something which illuminates. Maybe, too, our candle is lit by others and we are illuminated with a light that has been passed on to us. We somehow find a way to bring light into the world and there we are, with candle lit.

But this is not how light spreads. One candle, alone, does not illuminate a whole world of dark places, or even a whole city, or neighborhood, or even one room necessarily. To light up the world we must spread our light.

So we light our candle or let ourselves be lit, then we light two others. That makes three. But this is not enough, either, because three lit candles that will all wax and wane for a moment and then extinguish at the end of a life is surely not enough to illuminate a room, a neighborhood, or a world.

So what then?

The algorithm to spread light is simple, I think. It’s a compounding algorithm. We light our candle, then we light two others. But then, those two must light two others. And then those four light two others each. This is how light spreads, two by two by two. Light only spreads exponentially.

So what this means is that as parents, to really spread the light we cannot stop at being good parents, or teaching our kids how to be parents - we teach our kids to be teachers of parenting and be teachers of parenting ourselves. We cannot stop at being good people managers, or by mentoring the next generation of leaders, we must teach our mentees to make more mentors.

We can’t just make the light. We can’t just spread the light. We must teach others how to spread light. This is the algorithm for spreading light: light, spread, and teach how to spread.

—

We end with nothing.

What remains of us is what we leave behind. So a key question becomes, what should we try to leave behind?

First, I think we should leave behind something good. Something positive that benefits others and leaves the world better for us being there. Human life is a special thing, even after accounting for all the suffering it possesses. Why not leave something behind which honors this human life, this earth, and brings light to dark places?

It seems to me, that if we leave behind something positive and good we ought to leave something that endures, too. Leaving behind something enduring, that illuminates and gives light for a longer time, is better than something that fades quickly.

I don’t know if nothing lasts forever, or maybe some things last forever after all. But given the choice, why not strive for something closer to forever? But what endures, then? What lasts closer to forever?

Even if I were the wealthiest man alive, and passed down the largest inheritance - it would maybe last a few generations. All my photographs, too, will eventually become irrelevant. Our home will eventually change hands, and will be rebuilt or razed. My blog posts, hardly relevant to begin with will be forgotten. Anything that can be consumed, it seems, will eventually fade.

The chance we have then is to leave behind something that can regenerate itself?.

Kindness, for example, regenerates itself. Because when we are kind, it makes others kinder, and that in turn makes even more others kinder. Kindness regenerates. Knowledge is similar. When we create and share knowledge, it inspires the creation of new knowledge, leaving behind a larger body of knowledge from which to create. Knowledge also regenerates.

Good institutions are designed to regenerate. Think of the world’s leading companies and the most enduring governments.

The ones that last are built upon a premise of looking outward, seeing the new needs and having a genuine concern for a noble purpose. Those institutions then take the challenges of a changing world, channel them inward, and then regenerate themselves into something new. The moment that the most established of the world’s most high-profile institutions - like the world’s religions traditions, liberalism, Apple Computer, the US Constitution, or even Taylor Swift - stop regenerating themselves, they’ll begin to fade away like all the rest.

—

So the absolute, most essential question I could answer related to spreading the light is - what can I leave behind that’s positive and might actually last? If when I leave this world, I am only what I leave behind - what can I leave behind that regenerates and endures?

I don’t believe that careers and promotions are regenerative. The enduring impact of my position or title will start fading when I retire and end completely when I die. Nobody will care about my LinkedIn profile after I’m out of the game.

But what will last is a coaching tree of ethical and effective managers if I’m able to create one. What will last is the knowledge of unmet customer needs, if I’m able to bake that understanding into the DNA of companies and institutions. If I can build teams that don’t depend on fear, control, and hierarchy - and those teams actually succeed - they’ll regenerate and create more teams of their own. Those things regenerate, not my career in and of itself.

Simply having a happy marriage and happy children won’t regenerate either. What might last is if we can make such an impression on those around us and share all our secrets for a happy life, so that it starts a chain reaction which regenerates the families and marriages of others, that might endureHaving a wonderful marriage and happy children would be terrific, but those two achievements on their own won’t endure. What will endure is figuring out the secret sauce and then open sourcing the recipe.

When I talk to older people - whether friends or family - their concerns are different than mine. They seem less concerned with what they have and more concerned with what they can give back. As their time winds down, so does their ego. They start to look beyond their own lives.

What’s gut wrenching is when those people can’t prove to themselves that they’ve spread light. Or when they believe they haven’t prepared those that follow to spread light. Or worst of all, when they believe they’ve run out of time. Because spreading light and preparing others to spread light takes time. To see that realization is to witness agony.

—

What the hell have I been doing? For these past three decades, what have I been solving for? Have I been solving for building the world’s biggest candle? Have I been solving for lighting my own candle? Or have I been solving for spreading the light?

If I was solving for spreading the light, I think I would be acting so much differently than I am now.

I wouldn’t care as much about a career trajectory or a “dream job”, I’d just be walking the path of greatest different and would be spending much more time building up others to succeed and teach others.

I too, would be thinking about how to help others outside the four walls of our home, or at least really being generous with time and energy for the people who live near us or who are closest to us. I wouldn’t be waiting for the perfect cause to support or the perfect kid to mentor. I’d just be going for it and creating more builders of others.

And, I certainly wouldn’t be spending as much time pouting about all the others who behave badly toward me or be putting up a facade of politeness. If I was really solving for spreading the light, every conversation I had would be open, honest, sincere, and showing genuine concern for others. It’d be all heart and no polish.

If I were solving for spreading the light, I think I would be acting much differently. God willing, I have time to be different.

Photo by Rebecca Peterson-Hall on Unsplash

Corporate Strategy, CX, and the end of gun violence

Techniques from the disciplines of corporate strategy and customer experience can help define the problem of gun violence clearly and hasten its end.

What gut punches me about gun violence, beyond the acts of violence themselves, is not that we’ve seemed to make little progress in ending it. What grates me is that we shouldn’t expect to make progress. We shouldn’t expect progress because in the United States, generally speaking, we haven’t actually done the work to define the problem of gun violence clearly enough to even attempt solving it with any measure of confidence.

Gun violence is an incredibly difficult problem to solve, it’s layered, it’s complex, and the factors that affect gun violence are intertwined in knots upon knots across the domains of poverty, justice, health, civil rights, land use, and many others.

Moreover, it’s hard to prevent gun violence because different types of violence are fundamentally different, requiring different strategies and tactics. What it takes to prevent gang violence, for example, is extremely different from what it takes to prevent mass shootings. Forgive my pun, but in gun violence prevention, there’s no silver bullet.

I know this because I lived it and tried to be a small part in ending gun violence in Detroit. I partnered with people across neighborhoods, community groups, law enforcement, academia, government, the Church, foundations, and the social sector on gun violence prevention - the best of the best nationwide - when I worked in City Government, embedded in the equivalent of a special projects unit within the Detroit Police Department.

Preventing gun violence is the hardest challenge I’ve ever worked on, by far.

Just as I’ve seen gun violence prevention up close - I’ve also worked in the business functions of corporate strategy and customer experience (CX) for nearly my entire career - as a consultant at a top tier firm, as a graduate student in management, as a strategy professional in a multi-billion dollar enterprise, and as a thinker that has been grappling with and publishing work on the intricacies of management and organizations for over 15 years.

(Forgive me for that arrogant display of my resume, the internet doesn’t listen to people without believing they are credentialed).

I know from my time in Strategy and CX that difficult problems aren’t solved without focus, the discipline to make the problem smaller, accepting trade-offs, and empathizing deeply with the people we are trying to serve and change the behavior of.

This is why how we approach gun violence in the United States, generally speaking, grates me. Very little of the public discourse on gun violence prevention - outside of very small pockets, usually at the municipal level - gives me faith that we’re committed to the hard work of focusing, making the problem smaller, accepting trade-offs and empathizing deeply with the people - shooters and victims - we are trying to change the behavior of.

If I had to guess, there are probably less than 100 people across the country who have lived gun violence prevention and business strategy up close, and I’m one of them. The solutions to gun violence will continue to be elusive, I’m sure - just “applying business” to it won’t solve the problem.

However, all problems, especially elusive ones like gun violence, are basically impossible to solve until they are defined clearly and the strategy to achieve the intended outcome is focused and clearly communicated. To understand and frame the problem of gun violence, approaches from strategy and CX are remarkably helpful.

This post is my pitch and the simplest playbook I can think of for applying field-tested practices from the disciplines of strategy and CX to gun violence prevention. My hope is that by applying these techniques, gun violence could become a set of solvable problems. Not easy, but solvable nonetheless.

If you can’t put it briefly and in writing the strategy isn’t good enough

The easiest, low-tech, test of a strategy, is whether it can be communicated in narrative form, in one or two pages. If someone trying to lead change can do this effectively, it probably means the strategy and how it’s articulated is sound. If not, that change leader should not expect to achieve the result they intend.

The statement that follows below is entirely made up, but it’s an illustration of what clear strategic intent can look like. I’ve written it for the imaginary community of “Patriotsville”, but the framework I’ve used to write it could be applied by any organization, for any transformation - not just an end to gun violence. Further below I’ll unpack the statement section by section to explain the underlying concepts borrowed from business strategy and CX and some ideas on how to apply them.

Instead of platitudes like, “we need change” or “enough is enough” or “the time is now”, imagine if a change leader trying to end gun violence made a public statement closer to the one below. Would you have more or less confidence in your community’s ability to end gun violence than you do now?

Two-Pager of Strategic Intent to End Gun Violence in Patriotsville

We have a problem in Patriotsville, too many young people are dying from gunshot wounds. We know from looking at the data that the per capita rate of youth gun deaths in our community is 5x the national average. And when you look at the data further, accidental gun deaths are by far the largest type of gun death among youth in Patriotsville, accounting for 60% of all youths who die in our community each year. This is unacceptable and senseless heartbreak that’s ripping our community apart by the seams.

I know we can do better - we can and we will eliminate all accidental shooting deaths in Patriotsville within 5 years. In five years, let’s have the front page stories about our youth be for their achievements and service to our community rather than their obituaries. By 2027 our vision is no more funerals for young people killed by accidental shootings. We should be celebrating graduations and growth, not lives lost too early from entirely preventable means.

We know there are other types of gun violence in our community, and those senseless death are no less important than accidental shootings. But we are choosing to focus on accidental shootings because of how severe the problem is and because we have the capability and the partnerships already in place to make tangible progress. As we start to bend the trajectory of accidental shootings, we will turn our focus to the next most prevalent form of gun violence in our community: domestic disputes that turn deadly.

Our community has tried to have gun buybacks and free distribution of gun locks before. For years we have done these things and nothing has changed. So we started to do more intentional research into the data, the scholarship, and best practices, yes. But more importantly, we started to talk directly with the families who have lost children to accidental shootings and those who have had near misses.

By trying to deeply understand the people we want to influence, we learned two very important things. First, we learned that the vast majority of accidental shootings in Patriotsville have victims between the ages of 2 and 6. This means, we have to focus on influencing the parents and caregivers of children between the ages of 2 and 6.