The essential role of aunts and uncles

“Aunts” and “Uncles” build resilient cultures - whether it’s in a family or a larger organization.

I have come to appreciate aunts and uncles more lately, because now I see the effect that they have on our sons.

I am just in awe of how loved the boys feel by their aunts and uncles, whether they are blood-relatives or just close friends that care about our children as if they were blood family. And the love of an aunt or uncle is different than what we can give them, it’s something more generous perhaps. It’s as if the boys know, “you are not my parents, but you care about me and love me for who I am anyway, and that makes me feel safe and valued.”

Seeing the special love of aunts and uncles in the lives of our boys, has reminded me of my own aunts and uncles. I never could put words to it before, but I feel that same special, freely given, unconditional love from them. Thinking about it in retrospect, the love and support of my aunts and uncles has been a stabilizing force in my life.

I remember when my car broke down on the way into New York after college - miles away from the George Washington Bridge - and my Masi and Massasahib and extended family rescued me from a shady mechanic shop in the middle of North Jersey.

Or when my uncles in India deliberately ripped on American domestic policy to get a rise out of me and make sure I had some fire and fight in me. Or all our family friends who subtly reminded me I was a good kid in the middle of high school, by letting me sit and listen and hang out while they talked about scientific discovery, foreign affairs, or literature.

Or when Robyn’s aunts and uncles pulled me in and made me feel like part of the family, even from the very first family dinner I met them at by telling me stories and asking me questions. And they showed up at my father’s funeral as if they had known me my entire life.

I think what’s special about the love of aunts and uncles is that it’s redundant, affirming, and honest. It builds stability and resilience because it’s not the primary, day-in-day out sort of relationship you lean on. But it’s there, waiting to catch you, and to pick you up. And at times, it’s only an aunt or uncle who can really sit you down and get you out of the muck because they are able to have unconditional love but also enough distance and objectivity to call it like they see it.

It’s this combination of redundancy, affirmation, and honesty that makes aunts and uncles so important for a family’s culture. Theirs is a moderating influence that kicks in when things are going wrong.

And the more I think of it, the more I believe that every organization and community needs people who play the role of an aunt or uncle to thrive. In a company, for example, “aunts and uncles” are the people who take an active interest in you and give you advice, but don’t manage you directly. I can think of dozens of people who have been that sort of guide from afar, for me or others. When you mentor and develop others for whom you aren’t directly responsible, it’s such a gift to the culture of the company.

The same dynamic exists in a city. There are plenty of people who don’t have formal responsibilities over something but raise people up anyway. It could be neighbors who aren’t a block captain, but throw parties on their block and keep an eye out for neighborhood kids. It could be successful business owners who give advice behind the scenes to those coming up, outside of the auspices of business incubators and mentor programs. It could be the elderly couple in the church parish who invite newlywed couples to have dinner once or twice a year and help to nurture them through the ebbs and flows of marriage. These little acts are gifts that build the culture of a City and make the community more resilient. Which, it seems, is exactly like what aunts and uncles do.

I organize my life around three pillars - being a husband, father, and citizen. But what I’m realizing is that “uncle” is a really important role that fits within this framework, that I want to be intentional about - despite how invisible that role may be.

Status fights and wasted talent

What to do if your company feels like a high-school cafeteria.

Companies, and really any organization, can function like a fight for status. This “fight” plays out in organizations the same way whether it’s a corporation, a community group, or a typical school cafeteria.

There’s a limited number of spots at the top of the pecking order, and the people up there are trying to stay there, and those that aren’t are either trying to claw to the top or survive by disengaging and staying out of the fray.

If you’re engaged in a fight for status there are two ways to win, as far as I can tell: knocking other people down or promoting yourself up.

Knocking other people down is what bullies do. They call you names in public, they flex their strength, they form cartels for protection, and they basically do anything to show their dominance. They become stronger when they make others weaker.

This is, of course, easy to relate to if you’ve ever been to middle school or have seen movies like Mean Girls or The Breakfast Club. However, the same sort of dominating behavior that lowers others’ status occurs in work environments.

“Bullies” in the work environment do things like interrupt you in a meeting, talk louder or longer than you, take credit for your work, exclude you from impactful projects, tell stories about your work (inaccurately) when you’re not there, pump up the reputation of people in their clique, or impose low-status “grunt work” on others. All these things are behaviors which lower the status of others. In the work environment, bullies get stronger by making others weaker.

The other way to win a status fight is to promote yourself up and manage your perception in the organization. In the work environment, tactics to promote yourself up include things like: advertising your professional or educational credentials, talking about your accomplishments (over and over), flashing your title, hopping around to seek promotions and avoid messy projects, or name dropping to affiliate yourself with someone who has high status.

Let’s put aside the fact that status fights are crummy to engage in, cause harm, and probably encourage ethically questionable behavior. What really offends me about organizations that function as a status fight is that they waste talent.

In a status-fight organizations people with lower status are treated poorly. And when that happens they don’t contribute their best work - either because they disengage to avoid conflict or because their efforts are actively discouraged or blocked.

Think of any organization you’ve ever been part of that functions like a status fight. Imagine if everyone in that organization of “lower status” was able to contribute 5% or 10% more to the customer, the community, or the broader culture. That 5 to 10% bump is not unreasonable, I think - it’s easy to contribute more when you’re not suffocating. What a waste, right?

Of course, not all organizations function like a status fight and I’ve been lucky to have been part of a few in my lifetime. I think of those organizations as participating in a “status quest” rather than a “status fight”. In a status-questing organization, status actually creates a virtuous cycle rather than a pernicious one.

A status quest, in the way that I mean it, is an organization that’s in pursuit of a difficult, important, noble purpose. Something that’s aspirational and generous, but also exceptionally difficult.

In these status-questing organizations the standard for performance (what you accomplish) and conduct (how you act) is set extremely high, because everyone knows it’s impossible to accomplish the important, noble, quest unless everyone is bringing their best work everyday and doing it virtuously.

And when the bar is set that high, everyone feels the tension of needing to hit the standard, because it’s hard. Whether it’s to achieve the quest or be seen by their peers as making a generous contribution to the organization’s efforts, everyone wants to do their part and needs the help of others.

And as a result, the opposite dynamic of a status fight occurs. Instead of knocking other people down, people in a status-questing organization have no choice but to coach others up, which ultimately raises everyone’s status.

If you’re on a noble quest, there’s plenty of “status” to go around and the organization can’t afford to waste the contribution of anybody in the building - whether it’s the person answering the phone or a senior executive. In a status-questing organization, the rational decision is to raise the bar and coach instead of throw other people under the bus.

And what’s nice, is that in an organization with that raise-the-bar-and-coach-others-up dynamic is that the bullies don’t succeed, because their inability to raise and coach is made visible. And then they leave. And so the virtuous cycle intensifies.

So if you’re in an organization that feels more like a high-school cafeteria than an expeditionary force of a noble, virtuous quest, my advice to you is this: raise the bar of performance and conduct for the part of the organization you’re responsible for - even if it’s just yourself. And once you raise the bar, coach yourself and others up to it.

And when you do that, you’ll start to notice (and attract) the other people in the organization who are also interested in being on a noble quest, rather than a status fight. Find ways to team up with those people, and then keep raising the bar and coaching up to it. Raise and coach, raise and coach, over and over until the entire organization is on a status quest and any “bullies” that remain choose to leave.

Of course, this is one person’s advice. Looking back on it, it’s how I’ve operated (but I honestly didn’t realize this is how I rolled until writing this piece) and it’s served me well. Sure, I haven’t had a fast-track career with a string of promotions every two years or anything, but I have done work that I’m proud of, I’ve conducted myself in a way that I’m proud of, and I have a clear conscience, which has been a worthwhile trade-off for me.

—

Note: this perspective on equality / the immorality of wasted talent is well-trodden ground, philosophically speaking. John Stuart Mill (and presumably his contemporaries) wrote about it. Here’s an explainer on Mill’s The Subjection of Women from Farnam Street that I just saw today. It’s a nice foray into Mill’s work on this topic.

Snapping out of social comparison

I snapped out of the LinkedIn doom loop by thinking about the sacrifices a counterfactual world would’ve required.

When I’m stuck in a rut of feeling like I don’t measure up to others’ accomplishments, the advice of “remember how lucky you are” or “don’t compare yourself to others” or “focus on being the best possible version of you” just doesn’t work for me. It never has.

And in general I suppose those are good pieces of advice. They just don’t help me get out of a cycle of comparing my accomplishments to the people I went to school with or am friends with on LinkedIn.

Most Saturdays, these days at least, we go on a family walk. We live a few blocks away from a neighborhood coffee shop and we go after breakfast. Bo gets a hot chocolate with whipped cream, Robyn gets a coffee with milk, and I treat myself to a mocha - it is the weekend after all. Riley gets a extra long walk with extra time for smells and Myles is content just looking around and feeling the breeze go by as he rides in the stroller’s front seat.

And today, instead of trying to convince myself to stop feeling down about not being as accomplished as my peers, I started to wonder about trade-offs. After all, I made choices - for better or worse - that led to the spot I’m in today. And I wondered, if I had made different choices, what would I have had to sacrifice?

And I quickly realized, if I had made different choices that led to more professional success (which is mostly what drives my feelings of insufficiency, relative to my peers) I would’ve probably had to give up two things: living in Michigan and being a present husband and father. Which are two sacrifices I was absolutely not willing to make.

More or less, this was the thought exercise I went through:

And sure, after doing this exercise there were a few things that I regret and would do differently, like working harder on graduate school apps or sacrificing some of house budget for lawn care (I am irrationally embarrassed about how much crabgrass and brown patches we have on our lawn).

But by and large, thinking about the sacrifices making different choices would’ve required helped me to snap out of the doom loop of social comparison. Trying to ignore the feeling of not measuring up never works. Think about sacrifices and trade offs, was remarkably helpful.

If you also struggle with measuring yourself up to others’ accomplishments, I hope this reframing of the question is helpful to you too.

When I’m feeling used up

How I respond to feeling used up is a choice. It’s a choice. It’s a choice.

As a general rule, I don’t advocate for myself. It’s not that I avoid it or find it uncomfortable, I never really think to do it. The reason why, making a long story short, is that I’m a people-pleaser. I’m motivated more by making someone’s day than I am by a feeling of personal accomplishment.

To be clear, this is a personality flaw. Because I am a people-pleaser, I end up feeling used and used up a lot. Other people ask for my time and energy and my default position is to say yes, which leaves me feeling depleted.

This is a choice, with trade-offs.

How I respond when I feel used up is also a choice.

On the one hand, I could start saying no. I could protect my time and energy by setting boundaries.

On the other hand, I could insist upon reciprocity. Doing so would make day-to-day life more of a give-and-take rather than a mostly-give and sometimes take.

And seemingly paradoxically, I could give more. By digging deep and giving more, I could practice and get better at expanding the boundaries of my very little heart, and learn to give without receiving just a little more.

In reality, I should probably do some amount of all these things. Honestly though, I hope I don’t have to set boundaries or insist upon reciprocity. I hope instead that I can dig deep within and give more when I feel used up. I hope I’m dutiful enough to give to others, even if it means bearing more weight and sacrificing status or personal accomplishment.

I don’t know if the sinews of ethics and purpose holding me together can sustain that. I am definitely a mortal man, and not a saint. But still, I hope that I can dig deep and give more. It seems to be the choice most likely to create the world I hope to live in and leave behind.

But the revelation here is that it is indeed a choice. I feel so much pressure from our culture that the way to handle feeling used up are things like, “say no” or “self-care” or “manage your career” or “give and take” or “know your worth”.

And all that probably has a time and a place for mortal men like me. But that’s not the only choice. This choice is what I’ve found comforting.

Another way to handle feeling used is to live by wisdom like, “service is the rent we pay” or “nothing in the world takes the place of persistence”or “no man is a failure who has friends” or “be honest and kind” or “the fruits of your actions are not for your enjoyment”.

How I respond to feeling used up is a choice.

Inputs of good communication

An example of what causes good communication to emerge within daily life.

As I walked upstairs to get dressed and brush my teeth this morning, I said to Robyn, “The tea is steeping, I just put it on.”

It’s common knowledge that poor communication usually leads to strained relationships, especially in marriage. And it dawned on me that I had been thinking about communication in our marriage without much depth.

The key I had been missing was understanding that the practice of good communication, structurally, has to do more with listening and self-awareness than an act of communication itself.

So back to the tea. I made a choice to tell Robyn that I had just put on our morning tea to steep, even though I wouldn’t be upstairs long and Robyn would obviously see that I had put the tea on, if she had gone into the kitchen.

So why did I tell her?

Well, earlier that morning Robyn and I had a conversation about tea and that I would make it. From that conversation, I could tell she was looking forward to having a cup of tea. From past experience, I know that she likes her tea to steep for a certain amount of minutes - usually at least two but no more than 5 or 6.

And I also realized that if I didn’t tell Robyn that I had put the tea on just then, she wouldn’t know exactly when I had. So if I ended up getting stuck upstairs - which I did in this case, flossing and putting away some clothes, I think - our tea may sit steeping for too long. Which means it would be overly strong and would be colder than we wanted it.

In this case, again, the communication I made was simply telling Robyn that I just put on our tea to steep. That turned out to be good communication, because it led to us having tea exactly the way we like it and we had no stress over me starting the tea and letting it steep to long - I didn’t feel guilty about it and Robyn wasn’t let down.

I didn’t think much about telling that to Robyn. That communication emerged organically, because I paid attention to what Robyn was saying about tea - both this morning and historically. And, I was thinking about how my action, going upstairs for a tooth brushing and a change of clothes - might affect her. And as a result of those two practices of listening and self-awareness, I blurted out a simple sentence about the status of our tea without thinking about it.

At the same time, Robyn acknowledged that I went upstairs and took it upon herself to finish our cups of tea so it was perfect by the time I came back downstairs. Because we were both listening and self-aware, we communicated well and having a lovely cup of tea this morning.

And of course, this one interaction would not have made or broken our marriage. But an otherwise stale interaction became a bid of love and mutual respect. I got to make Robyn tea and she got to finish it - we were both grateful to each other and felt loved by each other. And this was one small moment, but all these little interactions add up and fill up the piggy bank of trust in our relationship.

So yeah, good communication is great. But “good communication”, I’ve realized, is not just an exercise in expressing yourself clearly in words or body language. Listening and self-awareness are two structural inputs of good communication.

So if we want to communicate better we should focus there - rather than just trying to “communicate more” or “communicate better”. Good communication can’t help but emerge when we listen and try to understand the impact we have on other people.

And for sure, Robyn and I have lapses and don’t communicate well sometimes, so I don’t mean this story to be self-aggrandizing. Instead, I share this story because we all know that relationships, especially marriages, depend on good communication. Most people I’ve encountered who advise that, however, do so without being specific about where “good communication” comes from or how to actually get better at it.

Walk beyond me

Myles - this is a memory of your first steps, and a reflection of mine for you to remember.

Myles,

8 days ago, my boy, you took your first steps. It was a Saturday. Your mother and I were in the family room with you on the floor and we were playing with Hot Wheels or magnets I think while your brother napped.

And you were up, holding onto your mother. And then you reached out to me, with your mouth-open smile, balanced, and took four steps toward me.

And we were so proud and happy for you. You are growing, and you are starting to cleave away from us, already, and take your own path in life.

But I want you to know, Myles, that those steps are not for me. You do not need to take steps - literally or figuratively - to please me. I am your father, but your life is not for my pleasure.

And you are our second child, as you know. And as it happens, your brother took his first steps in almost exactly the same place, in our family room. And you, son, need not follow in his footsteps, either. You are your own person, with your own gifts. We already see this. You and your brother are best friends, even now and I am overcome with a deep joy that you will be able to walk together in life. But you are each your own. You are each one of a kind.

It was a very sweet memory for your mother and I to have, to see you and hold you as you took your first steps. But this letter to you, also, is not for my pleasure. I want you to remember, yes, that your steps are not for me and nor do you have to follow the footsteps of your brother. But equally, I write this so you can remember that your steps are not fully yours alone either.

I hope you realize that the steps you take, matter. I hope you realize that you have the capability to carry others forward as you walk. I hope you choose to walk toward goodness and with righteousness with every step you take. I hope you walk with conviction and take steps in a direction that push our community and the human race forward. And I hope you relish the journey of love, honor, and service that is symbolized by the taking of a long walk.

But more than anything, Myles (and I mean this for your older brother too) that one day, you will walk past me. And you must walk past me. It is difficult for me to even acknowledge that one day I will not be able to walk with you. One day, I will be feeble and my footsteps will falter and I will return to our common father.

But know this: I want you to walk beyond the rim of the mountain where my life ends. I will carry you and your brother as far as I can. But as I falter, you must continue. You must walk beyond me. And don’t for a moment believe that I resent that you will reach lands and truths I will not. I will not look upon my departure from discovered to undiscovered country as a sunset of my own life. I will see that moment as the light of morning, where the moon and night ends, yes, but are eclipsed by a greater light.

You have taken your first steps, Myles, and you are well on your way. I will treasure the steps I get to take with you. But one day, when I return to dust, walk beyond me.

Love,

Your Papa

When our kids have hard days

I want to remember that the goal of parenting is not avoiding my own sadness.

The first words he said to me, as he had the purple towel draped generously over his wet hair and entire frame, were,

“It was a hard day, Papa.”

And then he melted into me, and I, on one knee, wrapped my arms around him and started to rub his back - both to help him dry off and comfort him. And we just stayed there, hugging on the bathroom floor for awhile.

And that’s one of the saddest type of moments I think I’ve had - when you’re kid is just sad. And yes even at three years old and change, he can have hard days and recognize that those days were hard.

And it wasn’t even that I felt and explosive, caustic sadness, where you feel the sadness growing and pushing out from core to skin. Like a sadness that smolders into my limbs and mind, and makes them feel like burning.

It was a depleting sadness, where I started to feel my heart shrinking, my bones and muscles hollowing, and my face and skin starting to feel...transparent maybe. It was a sadness that made me feel like I was disappearing.

When your own children - the ones you have a covenant with God and the universe to take care of - are truly sad, it’s a feeling you want to pass as quickly as possible, and never want to have again.

And when I realized that I “never want to feel this way again”, I started to get these two primal-feeling urges.

First I wanted to “fix it”. And “fixing it” has two benefits. First, it just stops this horrible feeling of depleting sadness. Because if I fix it, my son isn’t sad anymore, and therefore I’m not sad anymore.

But also, if I were the one who failed my son somehow and caused him to fall into this genuine sadness, fixing it is my redemption. Fixing the sadness is what helps me to feel like I’m not to blame. Because if I’ve fixed the external problem causing his sadness - the problem wasn’t me, it was that thing. Fixing it gives me the illusion that I’m the hero in this story, not the villain.

But beyond wanting to fix it, there was a more insidious urge, that crept on me slowly, was to believe this falsehood of, “maybe he’s just not ready” or “maybe we need to protect him more”.

And the fuzzy logic of that urge is this: If my kid is sad, there’s something out there that he can’t handle yet. And if I hold him back from going back out there, he’s less likely to have a hard day. Then he won’t be sad. And then I won’t feel this depleting sadness either.

But the problem with both of these responses is that if I find a way to let myself off the hook, it also deprives him of the opportunity to grow, and muddle his way through his sadness. Our kids will have hard days, and those days will suck. And on those days, we have to bring our best selves as parents. Because that’s when our kids need us to guide them, and love them, and coach them, and encourage them. And, many of those times we won’t be good enough; we will fail as parents and coaches. And they will have to muddle through that sadness for a longer. And we will feel depleted for longer, too.

But, damn. From those hard days, and that sadness, comes strength and confidence for our kids. Once they muddle through sadness, they have one more datapoint to add to their model to remind them that they can do this, they can figure this out, they can be themselves, they can be at peace, and they can rise up and through adversity.

And even though my instinct is to help my sons avoid sadness, I cannot let that instinct win. Because that instinct is selfish. What that motive truly is, is me wanting to avoid that horrible, depleting sadness that comes when your kids are sad.

Because these kids will have hard days. They will be sad. And even though my instinct is to make it stop as quickly as possible, and to never let this happen to them ever again, I must resist that selfish urge to fix their problems for them.

What I really need to do is comfort them, encourage them, love them, and coach them, and show them that no matter what happens I will be with them in this foxhole of sadness until they find a way out, no matter what.

And that I will be there, and support them in a way that doesn’t deprive them of the chance to come out of it stronger, kinder, and wiser.

The pizza stone, snowblower, and being that kind of man

I want to be humble and generous enough to give without receiving.

Two gifts I’ve been using a lot lately are a snowblower and a (2nd) pizza stone. Both were Christmas gifts from our parents in recent years.

The extra pizza stone has doubled our oven’s throughput for making pizza. Which is convenient for us a nuclear family, but it isn’t essential on a weekly basis. Where it makes a big difference is when we’re hosting - say close friends or family. Having that 2nd stone gives us the capability to throw a pizza party.

Similarly, the snowblower is convenient - especially on days of large snowfall - but not essential. I can muddle through with just a shovel if I really need to. Where the snowblower makes a huge difference is for our block.

Our next-door neighbors and we have an unwritten code: whoever gets to the shoveling first takes care of the others’ sidewalk. This makes it easier for whoever comes out second, and it clears more of the sidewalk, earlier in the day, for people walking down the block. Having the snowblower makes it much more possible for me to honor that neighborly code.

With the snowblower, I can basically guarantee I’ll be able to remove snow from our house, as well as for each of our next-door neighbors in about 30 minutes. Without the snowblower, it might take me closer to two hours on a day of heavy snowfall to manage that same task.

Receiving the stone and snowblower wasn’t a particularly flashy ordeal. Both were extremely generous and practical gifts, but it wasn’t particularly exciting to receive something so mundane, in the moment of unwrapping the present on Christmas day.

But these sorts of gifts, I’ve realized, are much more than practical. I’ve come to think of them as exponential because they give us the ability to give to others. In this example, the 2nd stone and snowblower has made the amount of times we’ll end up throwing pizza parties or helping out our neighbors over our lifetime exponentially greater.

I’ve thought recently, how humble one must have to be to give an exponential gift. When someone says “thanks for the pizza, it was great” I don’t, after all, make it a point to say something like, “You’re welcome, it would probably wouldn’t have happened if our parents hadn’t got us a 2nd pizza stone for Christmas 3 years ago.”

Or talking to our neighbors across the fence, I would never in a 100 years say something like, “No problem, I was happy to get your snow while I was out. The credit really goes to our parents who got us this snowblower. It would have been much harder to help you if not for their gift.”

And it’s not like I frequently say to our parents, “oh thanks for those gifts, it’s really helped me to be a better friend and neighbor.” Maybe I should, but that’s not really the sort of exchange I’d probably naturally have in real life.

Nobody knows the impact these gifts from our parents have had. Our parent’s probably don’t even realize it.

Essentially, when you give an exponential gift like a 2nd pizza stone or a snowblower, you can’t expect to get credit for it. This is much different than say a more novel gift that other people notice, like a consumer electronic or a very nice piece of new clothing.

Take a sweater I got this Christmas, for example. People noticed and said things like, “that’s a nice sweater, is it new?” And I could reply with something like, “oh yeah, I’ve loved it - it was a great Christmas gift from our parents.”

That sort of affirmation doesn’t happen with exponential gifts. Which is why I think giving an exponential gift takes tremendous generosity and humility, because the gift-giver isn’t recognized for it, nor might they even know how impactful their gift was.

And as I started contemplating this, I began to wonder - am I humble an generous enough to give gifts that nobody will ever know I was responsible for? And let’s put aside Christmas and birthdays and get to the big stuff.

What about in my job? Am I unconsciously holding back on making a contribution that I know won’t help me land a promotion? Am I working hard, just so I can get a pat on the back?

Do I volunteer in my community because I relish the credit and respect it provides, or because it’s just the right thing to do? Are there things I do, only because of how someone else might see it on instagram? Am I humble and generous, or am I just a peacock and a brat who gives only to get back reciprocally?

I don’t know how to know this, not yet at least. I think this problem - of knowing whether our own actions are done for their own righteous sake or because of the rewards we expect for them - is one of the essential, practical, moral struggles that we all face.

But I feel strongly that it’s important to try understanding this, and acting differently - more humbly and generously - if we can. Because exponential gifts are transformational in real people’s lives, and they transform the culture we live in for the better. I want to be humble and generous enough to give an exponential gift that I never expect to get any credit or recognition for.

I want to be that kind of man.

The Myth of Hard Work

What I was told would lead to success, led to fragility. Hard things, as it turns out, lead to courage and inner-strength.

My eldest sister, in her infinite wisdom, pointed out the subtle difference between hard WORK and HARD work, while we were WhatsApp video-ing across continents.

We were discussing a book we both happened to have read recently, Viktor Frankl’s Man’s Search for Meaning.

Which, if you haven’t read it, I think you should. It’s an essential work for us in this century, helping us to understand what it means to be human, the extremities of human experience, and the boundlessness of our inner strength.

“Why is it that in those extreme circumstances [of a Nazi death camp] some people could have such a response of strength and courage, while others did not?”, I asked her.

“Hard work,” she replied.

And so I pressed her. What kind of hard work? What kind of work should we do to build up our courage?

“Doesn’t matter,” she replied, again, thoughtfully. She continued and explained the difference to me. It doesn’t matter what the work is, as long as it’s challenging, and a struggle. To build our inner-strength and courage all that matters is that we do work that is hard.

If you’re like me - growing up in a well-to-do suburb, with educated parents - there is a myth you’ve probably been told. Everyone seems to be in on it.

If you work hard, you will make it, they tell us. You will be successful. You will have a good life. Perhaps you don’t even need to have grown up in a well-to-do suburb to have heard this myth. It’s pervasive in America.

Earlier in my twenties and thirties I thought this was a myth because hard work doesn’t necessarily lead to success, if you’re one of the people in this country who gets royally screwed because of your luck, the wealth you were born with, or one of many social identities.

What I got wrong, I think, is that there’s a bigger lie at play in the idea that hard work leads to a good life. The bigger lie, I think, is what hard work actually is.

When you’re told this myth, the hard work is presented like this:

Go to school, get good grades and get extra-curricular leadership credentials. That is hard. Get into a famous college, that is hard. Get good grades in an elite major at that famous college, that is hard. Then get a placement at an elite organization - could be an investment bank, could be a fellowship, could be a big tech firm, could even be an elite not-for-profit - that is hard. And do all this “hard” work and go forward and have a good, successful life.

What I realized after talking with my sister is that all that stuff isn’t actually the hard stuff. We perceive it to be “hard” because it’s made so artificially, through scarcity. It’s only hard to get into a famous college or into a plum placement because there are a fixed number of seats. It’s difficult to be sure, and one has to be skilled, but it’s a well trodden path that is hard to fail out of once you’re in it, that happens to have more applicants than seats.

And everybody knows this. Everybody, I think, who plays this game knows that there’s not that much special about them that got them to this point. It’s luck, taking advantage of the opportunities that have been given, and plodding along a well trodden path.

And I think most people, in their heart of hearts, knows that this game isn’t really hard because it’s not actually important. Degrees or lines on a resume don’t make a difference in the world. Getting a degree has no causal link to actually doing something of importance in the world. It’s an exercise to elevate our own status, without having to take any real risks or have any real skin in the game.

And I think this is why I have spent so much of my life having this fragile sense of accomplishment and confidence. I got good grades and was a “student leader” on paper and got into a good college. I did “well” there and got a placement at a prestigious firm where it was almost impossible to fail out. And so on.

Who cares? That didn’t create much value for anyone, save maybe for me. I was going down a well trodden path. I hadn’t actually done anything of any importance. And in my heart of hearts, I knew that. I felt like a fraud, because I was one. I hadn’t really done anything that hard or remarkable. I just played the game, didn’t fumble the ball I was handed, and was slightly luckier than the next person in line.

Of course I wouldn’t feel confident as a result of going down this well trodden path. Everything I had ever done was to build up a resume. That’s not hard.

So what’s hard?

Taking care of other people - whether it’s a child, a parent, a neighbor, or a sibling. It’s burying a loved one. It’s starting a company that actually makes other people’s lives better, even if it’s small. It’s taking that degree from a famous college and pushing from the bowels of a corporation, toward a new direction that actually solves a novel problem that everyone else thinks is ridiculous.

It’s marriage. It’s growing a garden from seeds. It’s baking a loaf of bread from scratch. It’s figuring out how to install a faucet because you don’t have the money to pay a plumber to do it. It’s making a sacrifice for others. It’s pulling a neighborhood kid out of trouble. It’s creating new knowledge and pioneering something nobody else has figured out. It’s telling the truth and being kind, consistently. This is the stuff that’s actually hard.

So yeah, one of the myths of hard work is that it leads to a good life - we know that isn’t fully true. But honestly, the bigger and more pernicious myth about hard work is that we’re lied to about what the truly important, hard work actually is.

The stuff we were told is “hard”, was all artificial and pursuing it left me fragile. It was only after getting chewed up by life in my late twenties, and going from fragile to broken, that I started to actually do the actually hard work of living.

And that’s when I actually started to feel inner-strength.

When I wasn’t trying to chase a promotion, but was actually trying to work on a team that was trying to reduce gun violence, because our neighbors and fellow citizens were literally dying. That’s hard. When I lost my father suddenly and was picking up the pieces of the life I thought I would’ve had, and the father-son friendship we were finally developing. That’s hard. When I fell in love with my soon-to-be wife, we were married, adopted a dog, and had children; being a husband and father, that’s hard. Monitoring my diet and trying to exercise, not because I wanted to look jacked at the bar, but because I’m confronting and trying to delay my own mortality. That’s hard.

And I say all this, at the risk of sounding like a humble-bragging narcissistic, because I still doom-scroll on LinkedIn, all the time.

I swaggle my thumb up and down the screen, seeing all the updates on promotions and new roles and elite grad school admissions. And I feel myself falling back into that hole of fragile pseudo-confidence, forgetting that I’ve learned all those accolades aren’t the hard work of real life. I forget the path of chasing status, money, and power is not the stuff that actually makes a difference in the world or what builds inner-strength and true courage.

I say all, out loud, this because I need help. I need help to not fall into that hole of that myth again. I need all of us in this collective - the collective that wants to live life differently than the myth we’ve been sold - to pull me back to the path of courage, goodness, and the hard and important work of real life.

And finally, I write all this, as a reminder that if you are also in this collective of living differently, we are in this together, and I am here to pull you back, out of the hole of that myth, too.

Noticing good days

I am trying to remove the concept of bad days out of my mind. Meaning, I’m trying to fully understand that the way I want to think about it is that bad days don’t exist.

There are so many wonderful things about days after all.

The sun, the wind, and the rain, and the fog, and the snow, and the hot and cold. There is deep breaths. There is the chance to wiggle my toes or have a glass of water. Or I can put on a sock. I can blink, just for fun or skip if I want to.

There’s also noise and touch and light, but also silence and the gentle darkness of stars and moonlight. And there’s the feeling of having a body, and things like sweating or a grumbling stomach. Or wishing or hoping or praying for something. Or a funny joke. Or the sweet relief of weeping about something.

And for me when Robyn says “good morning” and gives me a kiss, just about makes my day right when it starts. Or a hug from one of my boys or talking to our parents. Or a quick “hey” from an old friend, too. And I get that we are lucky to be enveloped in love and our relationships are bound by life, they still exist and will have existed.

These are all examples of little joys that actually aren’t little at all.

I’ve been thinking about it like fine chocolates. Many moments in a day are simply exquisite, like a morsel of well made chocolate. But even the finest chocolate can’t be noticed as exquisite if we just put it in our mouths, hurriedly, and just crunch-crunch-crunch, swallow and move on. And these little-but-actually-big joys are the same, even the most remarkable moments aren’t remarkable if we don’t savor them when we have them.

I know that bad moments happen. Sometimes, those moments are really horrific and truly terrible. But I want to also know in my bones and muscle tissues that bad moments don’t imply bad days. Bad moments can imply hard days, sad days, angry days, or even days of hopelessness and despair. But that doesn’t have to be bad.

And all this said, I know my days could be orders of magnitude harder if we weren’t as healthy, wealthy, or loved as we are. With temporal distance, even the hardest days of my life so far, like when I’ve done things that hurt others or the day I had to let my father go ahead without me, weren’t bad. They were unbearably hard, but I don’t have to think of them as bad, as if I wanted them to be wiped from existence.

Because if those days were wiped from existence, it’s one less day with all the good moments a day can have - even if those good moments are hidden in plain sight, waiting for us to notice them. If even one of those days were wiped from existence, I couldn’t have lived them.

And one definition of injustice to me is when there are people on this earth that have so many bad things happen to them that all the little things that can make a day good, even for a moment, remain hidden in plain sight. That they have so many struggles, and so much unbearable pain and disappointment that they aren’t capable of noticing even one good moment that day, even something as simple as the goodness of waking up from sleep or breathing.

I want my mind, my body, and my heart to understand what my soul already does: that good days don’t have to do with the trappings of how “lucky”, “blessed”, or “privileged” I am. That the “good” in a good day in life comes just from living. I want all of me to understand what my soul already does, that every day is a good day and every single one of those days matters.

Clear, shared, expectations: in projects and parenting

My wife made a brilliant parenting move this week.

Our older son is 3, and we’re trying to work on table manners with him. At least 5 days a week we have been getting into some sort of tussle with him over playing with his food, chewing with his mouth open, or deliberately making a mess. Mealtime has been the most common trigger of friction between us all.

And the other day I asked Robyn what she wanted to do, and she calmly replied, “I have a plan.”

What she did was simple and immediately effective. When we were serving the next meal, she set expectations for our son as she was putting down his plate. “The expectation is that we eat Cheerios with a spoon, blueberries you can eat with your hands.” And on she went about sitting down properly and what can be dipped and what cannot.

Her plan of setting clear expectations, in advance, worked immediately. It was a master stroke.

—

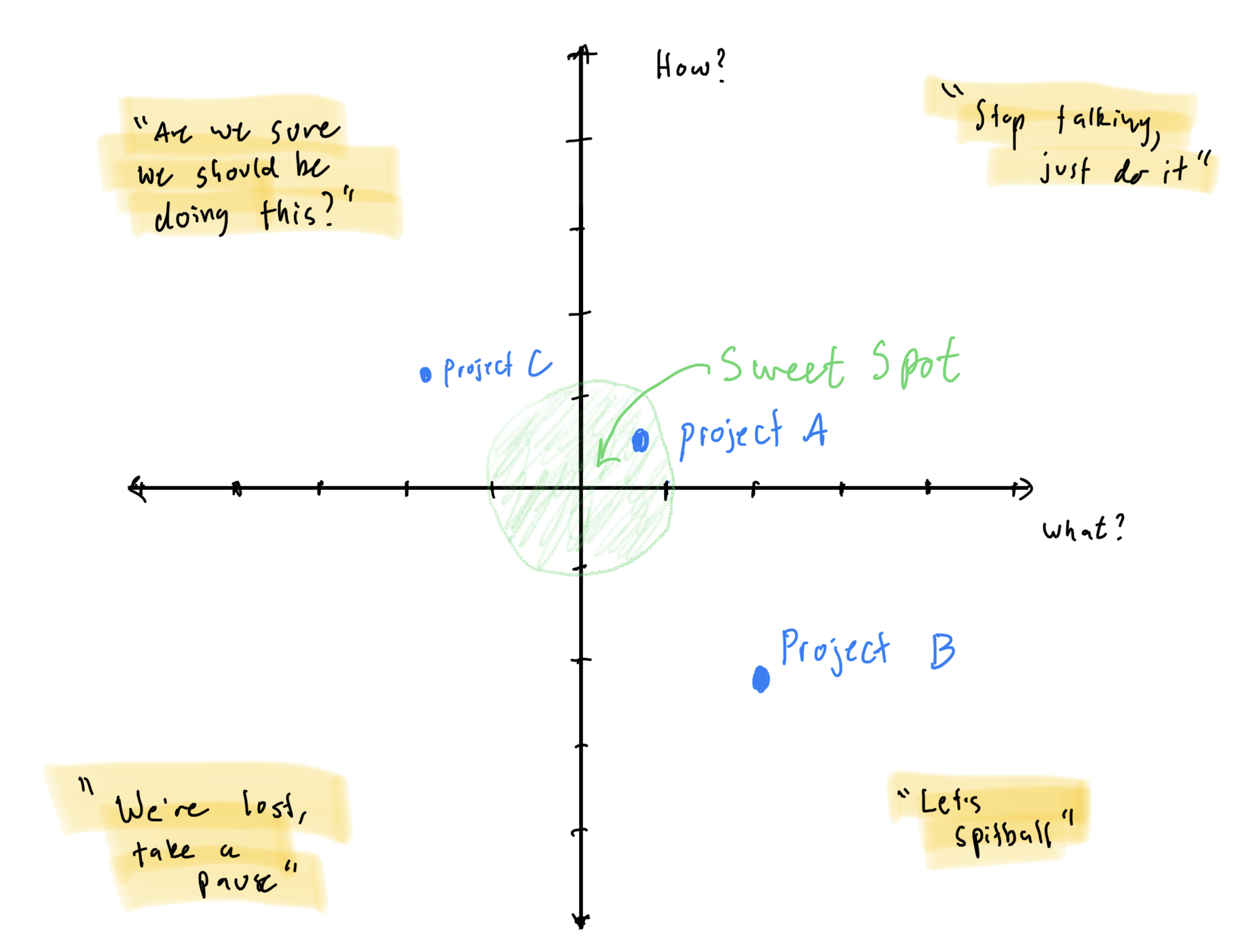

My work colleagues and I have been experimenting with approaches to clarify expectations, too. Instead of doing a weekly check-in with a traditional project board, we made a “why-what-how” board.

Here’s a representation of what our board (which is just a slide in PowerPoint) looks like:

What we do each week is re-score and re-plot our projects on this chart together. The goal of this exercise is to ensure the project is in the sweet spot of clear, shared, expectations.

The x-axis is the what. We make sure we understand what the intended outcome of the project is. Do we understand the deliverables? Do we understand what success looks like and what result we are trying to create? If the value is left of the origin it means the what isn’t clear enough. If the value is to the right of the origin, it means we are over analyzing the intended outcome and/or talking about it more than we need to.

The y-axis is the how. We make sure we understand the steps we need to take to achieve the intended outcome of the project. Do we understand the major milestones and next steps? Do we have a plan for how we’ll actually get the deliverables and analyses done? Do we understand the roadblocks ahead? If the value is below the origin, it means the how isn’t clear enough. If the value is above the origin, it means we’re micromanaging the project or getting too prescriptive about how it should be done.

We ask ourselves each week, usually during our Monday morning check-in, where are we at for each project. If we’re outside of the sweet spot, we spend some time clarifying the what, the how, or both.

Each quadrant, conveniently, has a nicely fitting heuristic which gives us a nudge on how to get back to the sweet spot:

High how, high what: we are talking too much. Let’s just take action.

Low how, high what: we understand what we’re trying to accomplish, but need to talk about how we get there. Let’s spitball and figure it out.

Low how, low what: we’re totally lost. We need to take a pause, reset and understand everything clearly where we are. This is the quadrant where the project is at risk and we have to dig out immediately.

High how, low what: this is the we might be wasting our time quadrant. If we don’t know what we’re trying to accomplish, even if we nail the project tactically, are we even solving the correct problem? We need to clarify the what (usually by escalating to the sponsor) or end the project.

What’s not plotted on the graph, but in the data table that powers the graph, are a few other elements: the why and who and the immediate next step.

The why and who has been a recent addition to our board, that we added a few weeks after trying this out for the first time. This value is the motivation for the project. Why does it matter, who is it for, what positive impact is this project in service of, why should anyone care about it? We think about our who as one of four general parties, that are applicable, honestly, to any organization. Any project has to ultimately impact at least one of these stakeholders in a big way to have a compelling why:

Our customer

Our owners or shareholders

Our colleagues

Our society or the communities in which we operate

If we can’t think of a compelling reason why what we’re doing matters to at least one of these four stakeholders, why are we even working on this project? We push ourselves to understand why, for our own motivation and to ensure we’re not doing something that doesn’t actually matter.

We also ensure everyone knows what the immediate next step is. If that’s not clear we establish it right there so there’s no reason we can’t take action right after our meeting.

Our team only started experimenting with this since the beginning of the year, but I’ve been finding it to be much more helpful than a traditional project board where the conversation revolves around the ambiguous concept of “status” and “accountability”.

Instead of checking our “status” non-specifically, and being reactive to a project that is “off-track”, we ensure that everyone on the team has clear, shared, expectations on each project, and we chip away at getting into the sweet spot of clarity on a weekly basis. By using this approach, we end up teasing out problems before they become large. Because after all, how often do projects get off-track if the why, what, and how of the project are clear to everyone, all the time? Rarely.

This approach is also much less autocratic than a traditional project board. Instead of the “manager” being dictatorial and projecting authority, this process feels much more democratic and equal, relatively at least. We all are working through the why, what, and the how together and even though one of us on the team is the titular “manager”, it feels more like we’re all on equal footing.

This is a good thing because everyone is more able to speak up, ask questions freely, and bring their talents forward to benefit the team and the people we’re serving. It’s less of an exercise where everyone is afraid of not having hit their milestones and therefore trying to tap dance around the status of the project.

There is of course a time and place for “status” and “accountability”. Of course, deadlines and results matter and we have to hit those. But what I’ve found so far is that by having clear, shared, expectations we are in a perpetual state of forward motion. We hit our deadlines as a natural consequence of having clarity. As is often said, but no less true, an ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure.

As is usually the case, what my wife and I are learning as parents is incredibly relevant to what we are learning about management and leadership. In this case the lesson is simple: clear, shared, expectations lead to better results (and less strife).

Paying Struggle Forward

I torture myself when a mission is going badly. Let’s say it’s a difficult project at work that I’m responsible for.

In the night, as I’m trying to fall asleep, I imagine myself in the CEO’s office, getting reprimanded, in front of my whole team. I feel the burn of my colleagues’ fearful, nauseated glances. I think about what I’m going to tell my wife, with a tail-between-legs posture, feeling like I embarrassed our family.

And when torturing myself in this self-imposed thought experiment, the bosses voice echoes enough to rattle my jaw. In my head I’m thinking, how did this happen, what was I thinking, why does this have to happen to me, why does it always have to be so hard?

But this week, in this particular version of my irrational thought experiment, the CEO asks me a question he never has:

“Why shouldn’t I fire you?”

And now, in a moment of clarity, I snap out of this hazy daydream. The answer is so clear to me. The boss shouldn’t fire me, because the next time we’re in this bad situation I won’t get beat. I’ve learned something.

Bad situations - whether it’s tough projects, losing a loved one, a failed relationship, an addiction, trauma, entrepreneurship, writing a book, climbing a mountain, you name it - are like viruses to me. They knock me on my ass. Sometimes, like viruses, bad situations quite literally make me ill.

But just as bad situations are like a virus, learning from our mistakes is like an immune response. Once we get through it, we’ve learned something. We’ve developed a sort of immuno-defense any time this particular bad situation comes up in the future. And I can share those anti-bodies with others.

The imaginary CEO shouldn’t fire me, I think in my head, because I now know a little bit about how to survive this bad situation, and I can tell the others how, too.

But that means I have to put this bad situation under a microscope and study it. I have to learn from it. I have to learn it well enough to teach others and then I have to actually teach others. Which means I have to tell the story of my struggle and failure again and again.

But reframing this into a process of learning from mistakes and teaching others makes the struggle feel meaningful. When I share what I’ve learned, I’m giving someone else a line of defense against this type of bad situation. They may not have to endure the same struggle as I did. And that is gratifying.

This was a mindset shift for me. In the past, when I’ve had bad situations happen, particularly at work, I’d just struggle. And I’d get angry. And I’d pout. And I’d just live with the struggle in a chronic condition sort of way for a long time. And I’d live in fear of the CEO’s office, or whoever the boss happened to be, until I had a new success to share.

I’ve had that utterly destructive thought of, why does life always have to be so hard, so many times, in so many types of bad situations. Like when my father died. Or when I choked on standardized tests. Or when I’ve had my heart broken. Or when I’ve been way over my head at work. Or when I’ve been up with a newborn that won’t sleep, for weeks at a time. Or when we’ve lived through a global pandemic. Or whatever.

But now I think there’s an opportunity to think differently. All these struggles are terrible, yes. But they don’t have to be in vain. They can be teachable moments, for me yes, but more importantly for others. I - and not just me, we - can give others some level of immunity from the deleterious effects of these bad situations that happen to us. But only if we’re wiling to share what we learn, humbly and specifically.

The option of paying our struggles forward to our children, our friends and families, our colleagues, and our neighbors seems much better than just living through them and forgetting about them.

Common bonds and unity that endures

The Hindu priest that married Robyn and I - to be clear, we were married twice: once by a Catholic priest, once by a Hindu pandit - left us with simple advice that we still remember and recite often:

From now on, you must be Together, Together, Together. Remember, Together, Together, Together.

From that day, Robyn and I were united in marriage.

But to be honest, I usually find myself wanting more when I hear the word “unity” uttered. Unity, to me, is a hollow word unless the common bond it invokes is specific and salient. Unity for what? Around what purpose? For whom? Unity bound by what beliefs?

In our marriage, and in the marriages of the people that we are close enough to see their marriages up close, I would say the beliefs that bind them are specific and salient. Here are some examples from our marriage:

Our vows: to love, honor, and cherish each other; for better or worse; for richer or for poorer, in sickness and in health, good times and in bad, until death do us part

Our common beliefs: belief in God; that we put family first, but that our marriage ultimately exists to serve others

Our common dreams: to grow old together, to grow a family and stay close to our international extended family, raise our children to be good people, to learn through travel, and be enmeshed in a community throughout our life

Our common experiences: the trips we’ve taken; the dates we’ve been on; the time we’ve spent doing nothing but enjoying each other’s company; the suffering we’ve navigated together; the little moments every day where we affirm, support, respect, and acknowledge each other and the investment of love all those moments - big and small - represent

If you’re a married person ( or expect you will someday) I do suggest trying to do a similar exercise where you specifically write down what the common bond that undergirds the unity you have with your spouse. I honestly had never done this until just now and I feel washed over with warmth, confidence, stability, and love.

I think this exercise is worth doing for more than just marriages. Any team or community that wants to endure also requires a durable common bond that is specific and salient. Asking the question “what unites us?” is just as relevant to companies, communities, and even states or nations.

The real hum-dinging implication, though, is how. How do we discover and articulate our common bonds? How do we create and nurture our common bonds? It’s not useful to merely describe that we need common bonds to have unity - that’s obvious. The very difficult question is how.

I’m planning a few posts over the next 4-6 weeks that push this idea of unity and the “how” of it further. But here’s a start: I think a good place to begin is interrogating our own beliefs, and asking what do I believe?

There was a terrific series some years ago that National Public Radio launched called This I Believe. The premise was simple: ask people to articulate their most core beliefs and then share them publicly. And when you hear some of those essays, you don’t just understand others’ beliefs cognitively, you feel and internalize them. We could all stand to write one of those essays and share it with the people we are close to.

Because after we understand our own beliefs, our next job - and I think it’s the harder and more important one - is to listen and deeply understand, feel, and internalize the beliefs of others.

And from there, we are well on our way to articulating our common bonds specifically and saliently - and developing a unity that is durable and enduring.

The One-way Door

At some point in the past five years, I accepted that the door Papa went through went one way.

It’s been five years since Papa went through the door.

In five years, a lot of life - our marriage, Riley, buying a home, changing jobs, a trip to India, a trip to Frankenmuth, family dinners and washed dishes, backyard barbecues and park walks, Bo’s whole life, Myles’s whole life, 5 Diwalis, 5 Thanksgivings, 5 Christmases, the Trump Presidency, a pandemic, two half marathons, knowing God again, a mostly written book, and many many moments of laughter and tears - has happened.

And for a long time, I knew he had already left. But, still, I thought he might come back through that door. Not in a real way, but in a fantasy sort of way. Like, in a waking up from a dream or being on candid camera sort of way. For a long time, a little part of me was holding onto the only-with-a-miracle possibility that he’d be back.

I don’t know exactly when, but sometime in the past five years I let go of that hope. I knew and thought he wouldn’t be coming back. Finally, I accepted that it was a one-way door.

And so what to do? It is true, the door is one way. And one day, I too, will head through it. That is certain. This is all certain.

Basically all of us have this predicament at some point in our lives. We have to accept that it’s a one way door, and choose what happens next. Do we sit and wait in a chair by the door, biding our time until our turn comes? And then, relief, because we have rejoined our loved ones who have already gone ahead?

Or, do we build a life on this side of the one-way door? Do we make memories and hang those pictures up beside it? Or cover the door in crayon drawings and finger paint? Do we build a table and cook and feast to celebrate life on this side of the door? Do we laugh and cry and yawp and run and play and blush and garden and read and mend things?

I feel guilty, often, for trying to build a life without him on this side of the door. Even though I know it’s not betrayal, I think it is. I know living life is what he would make me promise to do had he known he was going, but I still think something’s not right about it. I may never rid myself of this dissonance. I don’t know.

But the door no longer haunts me, on an hourly and daily basis like it used to. It’s pain that’s chronic and manageable, not acute and insufferable. But here I still am, five years later, torturing myself by reliving memories of his last days, while weeping tears of gratitude for the life we have now. And still, thinking of him, praying, and wondering how he is on the other side of the door.

The Weekly Coaching Conversation

Coaching others is definitely the most important and rewarding part of my job. When I took on this responsibility, I worried: would I waste my colleagues’ talent? How do I help them grow consistently and quickly?

Here’s a summary of what I‘ve been experimenting with.

Experiment 1: Dedicate 30 minutes to coaching every week

I raided my father-in-law’s collection of old business books and grabbed one called The Weekly Coaching Conversation: A Business Fable About Taking Your Game and Your Team to the Next Level.

The idea in it is simple: schedule a dedicated block of 30 minutes every week with each person you’re responsible for coaching. I thought it was worth trying. As it turns out, it was. Providing support, feedback, and advice falls by the wayside if it’s not part of the weekly calendar - at least for me.

Experiment 2: Ask Direct Questions

We start each 30 minute weekly meeting the same way, with a version of these two questions:

On a scale of 1-100 how much of your talent did we utilize vs. waste this week?

This question is useful because it’s direct feedback from the person I’m trying to coach. I can get a sense of what they need. Most of the time, what is holding them back is either me, or something I can support them with, such as: more clarity on the mission, an introduction to a subject-matter expert, some time to spitball ideas, or just some space to explore. This is also a helpful question to ask, because when the person I’m coaching is excited and thriving, I get to ask them why, and do more of it.

What’s one way you’re better than the person you were last week?

This question is useful because it helps make on-the-job learning more explicit and concrete. We get to unpack results and really see tangible progress. Additionally, I get a sense of what the person I’m coaching cares about getting better at which allows me to tailor how I coach them.

Experiment 3: Stop controlling the agenda

At the beginning, I would suggest an agenda for our weekly coaching sessions. But over the course of 3-5 weeks, I transitioned responsibility for setting the agenda to the person I’m coaching. This works out better because we end up focusing our time on what matters to them, rather than what I think matters to them (which is good, because I’m usually wrong about what matters to them).

It also works out well because my colleagues are in the driver’s seat for their own development. And that fosters intrinsic motivation for them, which is really important for fueling real growth. I certainly raise issues if I see them, but it frees up my headspace and my time to be responsive to what they ask of me.

I still have a lot of improvement to do here, but I spend a lot less time talking and much more time asking questions and being a sounding board by letting go of control of the agenda. Which seems to work out better for my colleagues’ growth.

What I’m thinking about now (I haven’t figured it out) how do I know that my support is actually working, and leading to real growth and development?

—

I am absolutely determined to discover ways to stop wasting talent, in my immediate surroundings and across the organizational world. It’s a moral issue for me. And I figure a world with less wasted talent starts with me wasting less talent.

I’ll continue to share reflections on what I’m experimenting with so all of us that care about unlocking the potential of people and teams have an excuse to find and talk to each other.

Radical Questions, Radical Diversity

By asking questions on facebook, I’ve learned the value of radical diversity and radical questions.

Over the holiday, my father-in-law asked me a very interesting question along these lines: after asking questions on facebook for so long, what have you learned?

Over these past five years or so of asking an almost-daily questions, I’ve tried not to ask gimmicky or empirical questions. I’ve tried to ask simple, specific questions that require reflection and emotional labor. This is not for any special reason, I just I think those sorts of questions are most interesting and yield the most wisdom on how to live a good life and be a good person.

What has been surprising is how often someone says something incredibly perceptive and relevant. Like, nearly every response I’ve ever received to any questions I’ve ever asked is something valuable. Individually, everyone has something profound to contribute.

At the same time, I’ve come to realize how deep but narrow of an understanding each of us have about the human experience. Nobody’s perspective fully explains or grasps the full truth on how to live a good life or be a good person. We all have a fragments of it. We all have a remarkably clear understanding on the little piece that’s been made clear to us by virtue of our most unique and compelling experiences.

If the truth of life were a large tree, we are not photographers standing from afar that can see the whole tree. Rather, we are each little birds that understand just the leaves and branches right around us.

Which leads me to two big takeaways - to understand the big truths of our human experience we need radical diversity and radical questions in our lives.

RADICAL DIVERSITY

The importance of diversity in teams trying to solve complex problems is not a new idea. Scott E. Page (Go Blue!) has done fascinating research in this area. I loved his book on the topic, The Difference: How the Power of Diversity Creates Better Groups, Firms, Schools, and Societies.

But what I would say, is that diversity isn’t just important for team problem solving. To understand the tree of human experience we need radical diversity in our live so that we can learn about the far reaching parts of the tree we’re all in, so to speak. Like, we don’t just need to learn from people who are different from us, they need to be radically different, from branches on the tree that are far, far away from us.

For example, there’s just some things that drug addicts understand better than others. Straight up. Or people who have lost parents early in life. Or people who have been bullied. Or people who have been insanely wealthy or dirt poor. Or people who have lived abroad. Or people who’ve had to execute massive projects. Or people who’ve studied the arts. Or people who have built things with their hands. Or people who have been abused. Or people who have raised children. Or people who have lied or have been lied to. Or people who have been to space. Or people who have served the most vulnerable. Or people who grew up in most typical suburbs. Or people who have been farmers. Or people who have committed heinous crimes and returned from prison.

Or whatever radical experience it is. There are just some things that folks who have had certain kinds of radical, intense experiences just understand better than I do. To really understand the human experience, I can’t settle for knowing people who are different than me - I have to learn from people who are radically different than me.

RADICAL QUESTIONS

At the same time, I will not learn much about the human experience, even if I have radical diversity in my life, if I only talk to those people about topics like the weather, sports, politics, or celebrity gossip.

To learn about human experience we have to talk about the radical things that have happened to us, which means we have to ask radical questions.

I don’t claim to be great at this yet, but I have learned a lot on how to ask good questions. And radical doesn’t mean sensational. It means questions that are reflective and require emotional labor.

And yes, I’d suggest that those sorts of questions are indeed radical. Because honestly, the bar on asking radical questions is really low. Even though the questions I tend to ask aren’t extremely radical most of the time, it’s easy to clear a very low bar.

Most questions that we’re ever asked in our day to day lives are boring and sanitized. Think about every customer feedback survey you’ve ever taken: boring. Think about every question asked during a panel discussion you’ve attend: boring or loaded with assumptions. Think about every question you’ve ever talked about chit chatting at a bar or waiting in line somewhere: boring or safe.

There are so few forums where we ask or are asked questions that require reflection or emotional labor. And so, all we ever learn about is our little twig on the tree of human experience, even if we’re surrounded by radical diversity.

And I’d also say that it’s not that scary to ask a radical question, though it may feel that way. If you haven’t, you should try it sometime.

We are so deprived of radical questions in our lives, I’ve found that many people seem to feel liberated when asked a radical question. We’re just waiting for the opportunity to share something radical, if we believe we are listened to, safe, and respected.

Radical listening and radical love in settings of radical diversity lead to radical answers to radical questions.

I think most people, at least my age, care about this wisdom of how to live a good life and be a good life. We can help each other do this. We really can.

Debrief questions for parents (and coaches)

We can’t “teach” our kids character, but we can debrief it.

I have been struggling for a long time thinking about how to teach our sons “character.” They won’t learn it from a book, nor will sending them to Catholic school magically make that happen.

What dawned on me this week, is that I can debrief with them. And really do that intentionally.

I attended a wonderful summer camp in high school, it was “student council camp.” And there were lots of character building-activities, that I still remember and think about often.

When I become a camp counselor, I had the opportunity to facilitate those character-building activities. And what we always said amongst other counselors is that it’s not the activity that teaches anything, “it’s all about the debrief.”

Debriefing - the process of helping others learn from their own experiences - is a hard-earned skill. It’s not easy. But it’s essentially all about asking the sequence of questions that highlight the salient information which lead to a a novel insight.

During a debrief, the goal isn’t to tell anyone anything, the goal is to nudge them along by bringing relevant facts to the debriefee’s attention which causes them to have an “aha moment”. In those aha moments, so to speak, they learn a lesson on their own. Good debriefers don’t teach, they help others teach themselves.

Cutting to the chase, I started putting a list of questions that could be used to debrief, even with young children. I needed to write them down to debrief myself I suppose.

I share that list here in case it’s useful to those of us that are parents or coaches. I also share it here in hopes that others share their own debrief questions. If you’re uncomfortable leaving a comment, please do contact me if you have a thought to share, I’d be happy to append it anonymously.

Debrief Questions for Parents and Coaches

How do you feel right now?

Are you okay?

Can you tell me exactly what happened?

Then what happened?

What were you thinking right before you did X?

How do you think this made [Name] feel?

What can you do to make this right?

Why didn’t X, Y, or Z happen instead?

What were you trying to do by doing X?

What could you have done instead of X?

Was doing X okay, or not okay? Why?

What else happened because you did X?

Do you have any questions for me?

What are you going to do differently next time?

What happens next, right now?

Reflection Questions: NYE 2020

Some questions in support of your 2020 holiday reflections.

Robyn and I (and our families) relish the last week of the year as a time to reflect on the year past and upcoming.

Here are a few reflection questions, many that we’ve talked about in our household over the past week. I wanted to share them, since this year in particular warrants reflection and prompts can be helpful.

But whether or not you use these prompts, I do think reflection - whether alone, with a friend, a partner, or a notebook - during this time of year is well worth it. I highly recommend taking at least a few quiet, contemplative minutes before you return to your usual routine.

Happy New Year!

Reflections that look backward:

What have you received this year?

What have you given this year?

How have you made life difficult or inconvenient for others this year?

What did you intend for 2020, and what actually happened?

What were your high points and low points? What emotions did you feel at those points?

What do you now know about how the world works, that you didn’t before?

What happiness or sadness are you still holding onto?

In what ways is your relationship different, or stronger?

How has your perception of life in your community changed this year? How has your view of the world changed?

What activities or people did you find a way to hang onto in some form?

What’s an event that you’d want your grandchildren to remember about this year? What lesson would you share with them?

Reflections that look forward:

What about this year would you continue in the future?

What about this year would you never opt to do again?

What do you intend for 2021?

How do you want to make your closest relationships, like your marriage, stronger in 2021?

What outcome that you want to happen is at the top of your list for 2021?

What’s a way that you want to behave differently in 2021?

What’s something you want to spend more time on in 2021? Less time on?

What phase of life are you transitioning into or out of?

What hard thing do you intend to tackle in 2021, even though you may fail?

What are some of the relationships you want to focus on in 2021?

What’s something that seems urgent but is really just a distraction for your most important 2021 priorities? (Pair with this post on anti-priorities).

Kitchen Table Entrepreneurship

We get up off the mat if and when something really, truly matters.

I have been trying my damndest this year to not give into the “that’s 2020” mentality. This whole year, I’ve been operating with a mantra of “get up off the mat, get up off the mat, get up off the mat.”

And let me start with honesty: I’ve failed on many fronts.

I didn’t finish this book, I shouted a lot at my sons, and attended church less, even though it was easier than before - to name a few ways I’ve failed.

But I’m encouraged. At the beginning of the year, I thought basically everyone but me had given up on 2020, as if it made you one of the cool kids to talk about how much 2020 sucked.

But this week, after taking a breath, it hit me how many people hadn’t given up on 2020, and were just going about their lives, quietly, but with tremendous courage and persistence.

In retrospect, I’ve seen an explosion of what I’d call “kitchen table entrepreneurship.”

By this, I don’t mean the venture-backed startups that develop software or some lifestyle product. Though I’m sure that’s continued.

I mean the ideas that were born around kitchen tables, in WhatsApp threads, or on Zoom calls by regular folks just trying to find a way to make things better for the people around them.

Like my sister-in-law who proclaimed it to be “Pajama Christmas” this year, rolled with three onsies to our family get together, and found a way for us to do a family social-distanced wine tasting after virtual church, complete with tasting scorecards to make up for the fact we couldn’t safely do our normal traditions.

Or the public servants in Detroit who just figured out how to rapidly build out drive-through Covid testing within days and weeks of the pandemic starting, put in protocols almost literally overnight to prevent the spread of Covid within DPD and DFD, launched a virtual concert of Detroit artists to help people stay sane, or delivered thousands of laptops to schoolchildren that didn’t have remote learning capabilities.

Or my wife, who’s been charging with some of her colleagues on legit, sincere Diversity and Inclusion programs and a Caregiver support group. She’s too humble to make noise about it, but she and her colleagues are doing really innovative work to change their particular workplace and improving the lives of their colleagues.

Or there are so many people who have figured out how to get their elderly neighbors groceries, or shovel their sidewalks, or get things like neighborhood storm drain cleanings coordinated even though some folks in the neighborhood barely knew how to send an email before this thing started, let alone join a Zoom call.

Or just today, I was able to use my Meijer App like a mobile cash register to scan my items as I shopped - minimizing time in the store and contacts with frontline employees.

Or our local businesses on Livernois, just turning on a dime to find ways to stay in business and operate safely. Narrow Way, our local coffee shop, is really efficient now, has used technology and new offerings to make their customer experience even better than it was before, and even though I’ve been in a mask, they still found a way to know me by name and make me feel respected and welcomed.

And even people who’ve had relative after relative get sick or pass away - I’ve heard so many stories of how they’re finding ways to get through, or continue to help others, or just keep doing what they do.

These are just examples from my own life, but they seem to be illustrative examples of people just making things better where they are, without a lot of money or a lot of fanfare. They’re just doing it.

Maybe this has always been happening and I haven’t noticed it as much. Either way, I think this kitchen table entrepreneurship is worth celebrating.