How to take more responsibility

If leadership is essentially an act of taking responsibility, how do we create teams where more people take responsibility?

“I’ll take responsibility for that.”

Hearing this phrase in a team setting is generally a good sign. Choosing to be responsible for something is effectively an act of leadership. And whether it’s in our families, at work, at church, or in community groups, more people choosing to lead is a good thing.

So instead of worrying about abstract concepts like “leadership development”, why not just focus on “taking responsibility”? If more folks - like us and our peers - are taking responsibility for their conduct and the needs of others, isn’t that exactly what we want?

One way to foster responsibility-taking is to make it clearer why taking responsibility is really important. This is fairly intuitive, it’s hard to convince someone to take responsibility for something if they believe it doesn’t matter. In my experience, people on teams don’t take responsibility if the challenge is unimportant, myself included.

Another way to foster more responsibility-taking is to build up competence. This is also intuitive, if someone feels like they’re definitely going to fail or have no idea what they’re doing, they don’t step up to take responsibility. For example, if someone asked me to take responsibility for making sure a car’s design was safe, I would say absolutely not. I do believe having safe automobiles is extremely important, but I am not comfortable taking responsibility for something in which I have no competence.

A third way to foster more responsibility-taking is to make teams non-toxic. I’d put it this way. Let’s say you’re in a meeting about a new problem that’s come up, maybe it’s a product safety recall your company has to do. You’re deciding whether or not to step up and take responsibility for executing the recall effort.

If you believed everyone would dump every last problem on you and vanish, would it make you more or less likely to step up? If you weren’t sure whether your boss would constantly overrule your decisions or if it seemed like your colleagues would scrutinize your work unfairly, would you volunteer? If you questioned whether or not you’d get the money and staff to solve the problem, or felt like you’d get all the blame for a mistake and no gratitude for a success, wouldn’t you think twice about taking responsibility?

I would, regardless of how important it was or how competent I felt. If the culture around us is toxic, we shouldn’t expect to see responsibility-taking.

In the American context, we tend to emphasize competence a lot. We like “all-stars” and “high-potentials” to save the day. There is a danger, however, to overindexing on this when assessing leadership. Competence (and also confidence) is easy to fake. It’s also easy to have hubris and think we have more competence than we really do.

I would also hypothesize there are diminishing marginal returns to competence. After a certain point, adding more competence doesn’t lead to more responsibility taking if importance isn’t clear or if a team has a toxic environment. If we want to increase responsibility-taking, competence matters, but it’s not the only thing that matters.

The big realization from this thought experiment came when I put these ideas into the context of our family.

I, like many others, want my kids to take responsibility for their actions and for helping others as they grow older. In fact, I believe that I owe it to them to help them learn how to do take responsibility. But no extra-curricular activity, or online video is going to do that for me. I cannot expect our kids’ school to teach them to take responsibility.

Rather, the responsibility lies with me. I have to explain to them why taking responsibility for something, like befriending a classmate who is struggling with a bully, is important. I have to create a non-toxic environment at home, and let them make decisions for themselves. I have to give them the time and support, and help them clean up a mess when they screw up - even if I knew beforehand that whatever they were doing was going to fail.

Sure, maybe at the margins, some sort of class, extra-curricular, or book is going to help them build up fundamental competence in some way, like say in how to run a meeting or how to manage the budget of their lemonade stand. But even then, I’ll still have to coach them - they won’t learn everything from a class, video, or book.

In a family setting, it seems to me that learning to take responsibility has much more to do with how we interact with our kids and shape our family’s culture than it does with sending them away to camp for a few weeks and assuming the “training” they receive there will be enough.

So why do we think “leadership training” at work would have different results? It seems to me that if we really want to create teams where more and more people take responsibility, having “leadership development” retreats or “high-potential talent pipelines” are a bit of a sideshow.

What we should be doing is telling stories about why the work we do is important. What we should be doing is finding really specific training courses to build up contextually-specific competence. What we should be doing is treating our colleagues with more compassion so they can count on a reasonable level of support and respect when they step up and take responsibility for a challenge.

I’m skeptical of the concept of “leadership” and have been for a long time. It seems to me that if I want other around me to take on more responsibility - whether it’s my family, my neighbors, or my colleagues - the biggest obstacle to that is not them and their “leadership abilities” or creating more “leadership development” opportunities. The biggest obstacle is probably me, and the way I treat them.

I am determined - 2020 will not become a hashtag | Hurricane-proof Purpose

A note about 2020, algorithming ourselves to find our individual higher purpose.

I am determined not to let this year, 2020, become a hashtag. Every time I hear the punchline of a joke or a meme end in something like, “well that’s 2020 for you” I cringe. To me it’s defeat. It’s a resignation that we do not have agency over our own fate, or at least our reaction to our fate. I am determined not to let 2020 become a hashtag, even if it’s just in my own head.

In most instances, this is where I’d insert an “easier said than done”, but I don’t think so. It’s actually very easy to bounce back from a “that’s 2020” mindset. All it takes is focus on a higher purpose.

If a higher purpose for my life is clear, then all I have to do is focus on that purpose. And just consistently think about that north star purpose and work on that. Focusing on that pre-established higher purpose pushes all of 2020’s qualms - both the legitimate trauma this year has brought, and the whining too - out of my mind.

The key is that purpose can’t be petty, shallow, or ego-driven. It has to be deep. It has to stir to the core. A higher purpose is only higher if it can withstand the hurricane times, like the ones we are living in. 2020 is not the hard part, building a hurricane-proof purpose is the hard part.

For me, that purpose falls into two parts - one related to my private life and the other related to my public life. I have been thinking about this for years, I think, and it’s starting to become clear. But my personal purpose is a bit beside the point right now. What really matters is, “how?”

Three friends of mine, Alison, Glenn, and Nydia, were among a handful that sent me some transformative comments to an early draft of a book I’m writing. Their particular comments pushed me on this point: the difficulty in living a purposeful life is not just living it consistently. That is hard, but how do we even figure it out? What’s the mental scaffolding we can lean on?

I have much more thinking and writing to do on this, but where it starts, for me at least, is being really good at noticing things. And luckily our mind, body, emotions, and perhaps even our soul are very sensitive instruments for finding these purpose-fulfilling moments if we calibrate them properly. Just listening to our mind, body, and gets us pretty far. But for that to work, we have to know how to listen and what we’re listening for.

Step one, I think, is calibration. Perhaps a good exercise is thinking of 5 or 10 instances where you had very strong emotions or were deeply immersed in thought. Maybe there are a couple of moments that you think about obsessively, even though they were seemingly small.

And when I think about my 5 or 10, some of them are self-indulgent feelings. They are times when I had a strong emotional reaction because of external affirmations, power, recognition, and ego. Throw those times out of your sample, they are false positives. Those aren’t the moments that lead to a discovery of higher purpose, in my experience. Rather, those are the moments that have taken me in the precisely wrong direction.

And then, remember those remaining moments vividly in your mind. Really feel them. How would you describe those feelings? Let your guard down, and let the deep feelings of peace, joy, or courage flow through your body. Try to amplify the feeling until you feel it in your torso or your limbs. Get to cloud nine. Go higher. Get to the place where you know in your bones that something about this memory is related to a hurricane-proof purpose. This feeling is your filter to exclude the memories and experiences that are false positives.

Step two, I think, is adding data to your dataset. Think of all the times where you feel similar feelings of deep emotional courage, peace, and joy. Think of all the times where there was something that stirred in you nobly. Think of all the times you felt flow or a state of pure play. As you go through your day, take a pause if you feel the beginnings of those feelings.

Organize these moments in your mind, write them down if you have to. Get as many data points as you can, being careful to separate out the moments that are simply ego-boosters and not examples of the deep, purposeful stirrings we’re looking for. Try to filter out the false positives.

I find zen meditation techniques to be helpful practice for getting better at this type of noticing.

Then explore the data and find the patterns. Talk about it, journal about it, do whatever you have to do. Slowly, the right words to describe purpose emerges. And then it changes as you get more data. And as you get more data, your filter gets better too. It’s very bayesian in a way.

This post became something much different than I originally intended. Whoops.

But the point is, I am personally determined not to let 2020 become a hashtag. The best antidote I can think of is focusing on a higher purpose. It’s easy to say go do it, so these reflections are the best advice I have to offer, so far, as to what that higher purpose may be for you.

I don’t know what help I can be, but please let me know if you think there’s something I can do to support you if you’re on this type of journey. It’s kind of like applying an algorithm to ourselves and what we feel.

Visualizing the Highest Version of Ourselves

A thought experiment, just like an athlete would do to visualize their peak athletic performance.

I feel so many pressures to “be” very specific, culturally-prescribed, things. Be productive. Be smart. Be professional. Be loving and kind. Be pious. Be cool.

And being all these things is so confusing, because being one seems to conflict with another, much of the time.

Lately, I’ve wondering if I could stop trying to be something specific and try to just be the highest version of myself. Paradoxically, maybe trying to be the best of everything would actually be liberating.

And that’s when this thought experiment came to be. Like an athlete visualizing peak performance in their sport, what if I picked a specific environment in my day-to-day life and just visualized being the “highest” version of myself? It could be in a meeting at work. When with my family on vacation. When running. When mowing the lawn. Doesn’t matter - it could be any environment.

In any environment, what if we tried to imagine the highest version of ourselves? Would we be more likely to live up to it? Would the process change us? Would we be more or less frustrated at ourselves?

I didn’t know, so I gave it a try. I don’t think you need to read my reflection (below), unless you want to. I include it only to illustrate what I mean.

What I will say is this, I did this on a whim, just to see what would happen. And I don’t know what will happen in the future.

But after I did this thought experiment (in italics below), I had a tingling feeling in my lower abdomen. Not the queasy stomach feeling, but the kind of tingling you feel when you are about to give someone a gift on their birthday. Or the butterflies you get at the last step before solving an equation in math class. Or when the curtain goes up at the theater.

If you want to, give it a try. Just take the sentence below and replace what’s after the ellipsis with something relevant to you. I hope you get the same warm, tingling feeling if you try it for yourself.

I close my eyes as I type this, and push myself to imagine the highest version of myself in a typical situation…in this case when eating dinner, with my family, on a week night, 12 years from now.

I am at the dinner table. Specifically, our dinner table at home with my wife and kids. It is about 12 years from now - say in 2032. We are eating tacos, the same way we have every other Tuesday for nearly 15 years. It’s early autumn. We all sit quietly and pass our dinner around the table, everyone taking a turn. We are light and easy and comfortable feeling, because we are home. Robyn is laughing with one of the boys about a new joke they heard from a son’s friend on their way home from school - Robyn had pickup duty today. I laugh as I put a dollop of sour cream atop a small mound of avocado. Even though I am assembling a taco, I’m paying close attention to everyone. I look up, giggling at the joke.

I scan the room with my eyes only, this is my opportunity to check how everyone is feeling. If they are laughing as they normally do, all is well. I see our other son crack a smile but he doesn’t laugh. Hmm, how unlike him.

I quickly look down at everyone’s plate. Normal, normal, normal, hmm. Our same son, the one that didn’t laugh didn’t take as many tomatoes as he normally does. How unlike him. I sit up straight and start my meal, keeping him in the corner of my eye softly.

We do our nightly ritual of catching up on the day, and we do our “highs and lows”. My son seems to be his normal self, but his eyes are wandering a little bit. There’s something distracting him. I decide instantaneously that I should try talking to him after dinner. I mentally note that and focus my attention back on the entire family and our meal, so I don’t disengage myself.

As we start to break from the table, I ask, “Son, could you help me store the dog food? It’s a pretty big bag and my wrist still hurts from playing tennis yesterday.”

I probably could store the dog food myself. But my wrist IS still sore and I want to create the space for him to open up.

I ask him as he opens the container, “So bud, what have you been thinking about lately?” As he pours the kibble into the bucket, he starts to talk. He mentions a friend off-hand and how he had to cancel on their weekly study session.

I see my opening, but I opt not to take it. Instead I say, “Hey bud, since you’re already over here would you mind helping me load the dishwasher?” When he agrees, I smile extra wide and say thank you.

We chit chat the whole time. Just as we load our last plate, my son pauses, seeming to collect his thoughts. And then he hesitates. I wait . Then I gently raise my eyebrows to let him know that it’s his turn to speak if he wants to.

He takes my cue. Then he says, “Hey papa, have any of your friends ever avoided you?”

I take a moment, and pour two glasses of water. I motion him over to the now spotless dinner table.

“Yeah bud, sometimes. Let’s relax for a minute and I’ll tell you about it.”

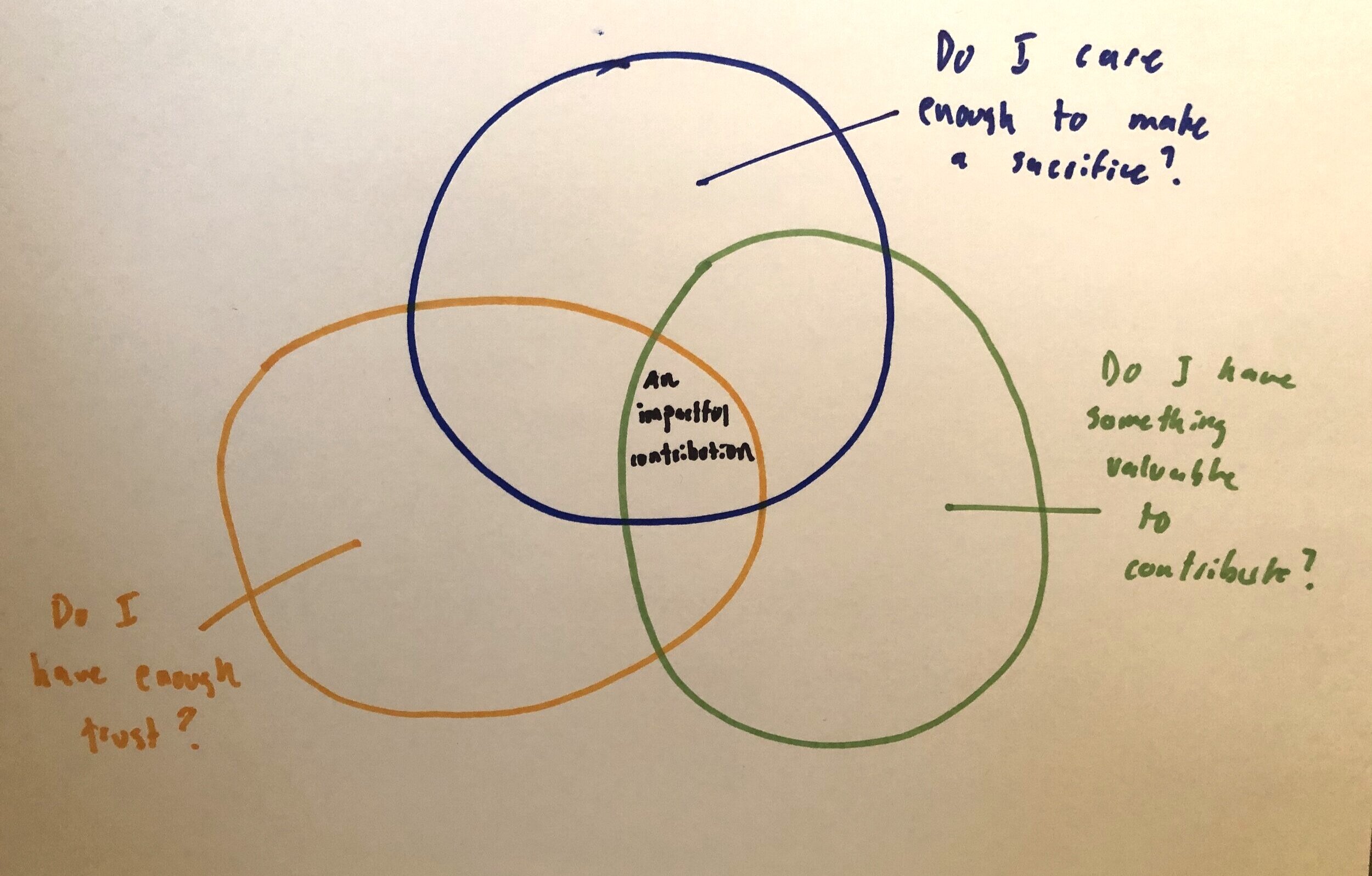

Impactful Contribution

When I’ve already committed to making an impactful contribution, what will I do?

This image of ikigai has been floating around the internet in various forms for a while.

And even though I’m generally skeptical of advice that emphasizes “doing what you love”, I don’t see any reason to criticize the concept the diagram argues for. Those four questions seem sensible enough to me when thinking broadly about the question of “what do I want to do with my life?”

Lately though, in the aftermath of George Floyd’s murder, as protests continue throughout our country, I’ve heard a lot of people ask - “what can I do?”

In this case, the question of “what can I do?” is not a decision where the framework of ikigai easily applies. When it comes to racial equity, if we’re asking the question of what can I do, we’re already committed to issue area and we aren’t expecting to be paid for it.

And this question is common. I have often asked myself, something like what do I want to do to contribute to others when I’m not at work? Nobody has unlimited leisure time, but most of us have some amount of time we want to use to serve others, after we complete our work and home responsibilities. We’re already committed to doing something for others, we just don’t know what to do.

So the question becomes: when I’ve already committed to making an impactful contribution, what will I do?

Here’s how i’ve been thinking about approaching that question lately:

There are three key questions to answer and find the intersection of:

Do I have enough trust to make an impactful contribution?

if so, where?

If not, how can I build it?

Do I have something valuable to contribute?

If so, what is it?

If not, what can I get better at that is helpful to others?

I I don’t know what’s helpful, how do I listen and learn?

Do I care enough (about anyone else) to make a sacrifice?

If so, who is it that I care so deeply about serving?

If not, how do I learn to love others enough to serve them?

Our decision calculus changes when we not trying to determine what to based on whether it will make us feel good. When we’re looking to serve others, it’s not as important to find something we are passionate about doing or finding something which helps us seem important and generous to our peers. What becomes most important is putting ourselves in a position to make an impactful contribution.

Because when we’ve already committed to making an impactful contribution, making that contribution is it’s own reward. We don’t depend as much on recognition to stay motivated. As long as we’re treated with respect, we’re probably just grateful for the opportunity to serve.