The Myth of Hard Work

What I was told would lead to success, led to fragility. Hard things, as it turns out, lead to courage and inner-strength.

My eldest sister, in her infinite wisdom, pointed out the subtle difference between hard WORK and HARD work, while we were WhatsApp video-ing across continents.

We were discussing a book we both happened to have read recently, Viktor Frankl’s Man’s Search for Meaning.

Which, if you haven’t read it, I think you should. It’s an essential work for us in this century, helping us to understand what it means to be human, the extremities of human experience, and the boundlessness of our inner strength.

“Why is it that in those extreme circumstances [of a Nazi death camp] some people could have such a response of strength and courage, while others did not?”, I asked her.

“Hard work,” she replied.

And so I pressed her. What kind of hard work? What kind of work should we do to build up our courage?

“Doesn’t matter,” she replied, again, thoughtfully. She continued and explained the difference to me. It doesn’t matter what the work is, as long as it’s challenging, and a struggle. To build our inner-strength and courage all that matters is that we do work that is hard.

If you’re like me - growing up in a well-to-do suburb, with educated parents - there is a myth you’ve probably been told. Everyone seems to be in on it.

If you work hard, you will make it, they tell us. You will be successful. You will have a good life. Perhaps you don’t even need to have grown up in a well-to-do suburb to have heard this myth. It’s pervasive in America.

Earlier in my twenties and thirties I thought this was a myth because hard work doesn’t necessarily lead to success, if you’re one of the people in this country who gets royally screwed because of your luck, the wealth you were born with, or one of many social identities.

What I got wrong, I think, is that there’s a bigger lie at play in the idea that hard work leads to a good life. The bigger lie, I think, is what hard work actually is.

When you’re told this myth, the hard work is presented like this:

Go to school, get good grades and get extra-curricular leadership credentials. That is hard. Get into a famous college, that is hard. Get good grades in an elite major at that famous college, that is hard. Then get a placement at an elite organization - could be an investment bank, could be a fellowship, could be a big tech firm, could even be an elite not-for-profit - that is hard. And do all this “hard” work and go forward and have a good, successful life.

What I realized after talking with my sister is that all that stuff isn’t actually the hard stuff. We perceive it to be “hard” because it’s made so artificially, through scarcity. It’s only hard to get into a famous college or into a plum placement because there are a fixed number of seats. It’s difficult to be sure, and one has to be skilled, but it’s a well trodden path that is hard to fail out of once you’re in it, that happens to have more applicants than seats.

And everybody knows this. Everybody, I think, who plays this game knows that there’s not that much special about them that got them to this point. It’s luck, taking advantage of the opportunities that have been given, and plodding along a well trodden path.

And I think most people, in their heart of hearts, knows that this game isn’t really hard because it’s not actually important. Degrees or lines on a resume don’t make a difference in the world. Getting a degree has no causal link to actually doing something of importance in the world. It’s an exercise to elevate our own status, without having to take any real risks or have any real skin in the game.

And I think this is why I have spent so much of my life having this fragile sense of accomplishment and confidence. I got good grades and was a “student leader” on paper and got into a good college. I did “well” there and got a placement at a prestigious firm where it was almost impossible to fail out. And so on.

Who cares? That didn’t create much value for anyone, save maybe for me. I was going down a well trodden path. I hadn’t actually done anything of any importance. And in my heart of hearts, I knew that. I felt like a fraud, because I was one. I hadn’t really done anything that hard or remarkable. I just played the game, didn’t fumble the ball I was handed, and was slightly luckier than the next person in line.

Of course I wouldn’t feel confident as a result of going down this well trodden path. Everything I had ever done was to build up a resume. That’s not hard.

So what’s hard?

Taking care of other people - whether it’s a child, a parent, a neighbor, or a sibling. It’s burying a loved one. It’s starting a company that actually makes other people’s lives better, even if it’s small. It’s taking that degree from a famous college and pushing from the bowels of a corporation, toward a new direction that actually solves a novel problem that everyone else thinks is ridiculous.

It’s marriage. It’s growing a garden from seeds. It’s baking a loaf of bread from scratch. It’s figuring out how to install a faucet because you don’t have the money to pay a plumber to do it. It’s making a sacrifice for others. It’s pulling a neighborhood kid out of trouble. It’s creating new knowledge and pioneering something nobody else has figured out. It’s telling the truth and being kind, consistently. This is the stuff that’s actually hard.

So yeah, one of the myths of hard work is that it leads to a good life - we know that isn’t fully true. But honestly, the bigger and more pernicious myth about hard work is that we’re lied to about what the truly important, hard work actually is.

The stuff we were told is “hard”, was all artificial and pursuing it left me fragile. It was only after getting chewed up by life in my late twenties, and going from fragile to broken, that I started to actually do the actually hard work of living.

And that’s when I actually started to feel inner-strength.

When I wasn’t trying to chase a promotion, but was actually trying to work on a team that was trying to reduce gun violence, because our neighbors and fellow citizens were literally dying. That’s hard. When I lost my father suddenly and was picking up the pieces of the life I thought I would’ve had, and the father-son friendship we were finally developing. That’s hard. When I fell in love with my soon-to-be wife, we were married, adopted a dog, and had children; being a husband and father, that’s hard. Monitoring my diet and trying to exercise, not because I wanted to look jacked at the bar, but because I’m confronting and trying to delay my own mortality. That’s hard.

And I say all this, at the risk of sounding like a humble-bragging narcissistic, because I still doom-scroll on LinkedIn, all the time.

I swaggle my thumb up and down the screen, seeing all the updates on promotions and new roles and elite grad school admissions. And I feel myself falling back into that hole of fragile pseudo-confidence, forgetting that I’ve learned all those accolades aren’t the hard work of real life. I forget the path of chasing status, money, and power is not the stuff that actually makes a difference in the world or what builds inner-strength and true courage.

I say all, out loud, this because I need help. I need help to not fall into that hole of that myth again. I need all of us in this collective - the collective that wants to live life differently than the myth we’ve been sold - to pull me back to the path of courage, goodness, and the hard and important work of real life.

And finally, I write all this, as a reminder that if you are also in this collective of living differently, we are in this together, and I am here to pull you back, out of the hole of that myth, too.

Noticing good days

I am trying to remove the concept of bad days out of my mind. Meaning, I’m trying to fully understand that the way I want to think about it is that bad days don’t exist.

There are so many wonderful things about days after all.

The sun, the wind, and the rain, and the fog, and the snow, and the hot and cold. There is deep breaths. There is the chance to wiggle my toes or have a glass of water. Or I can put on a sock. I can blink, just for fun or skip if I want to.

There’s also noise and touch and light, but also silence and the gentle darkness of stars and moonlight. And there’s the feeling of having a body, and things like sweating or a grumbling stomach. Or wishing or hoping or praying for something. Or a funny joke. Or the sweet relief of weeping about something.

And for me when Robyn says “good morning” and gives me a kiss, just about makes my day right when it starts. Or a hug from one of my boys or talking to our parents. Or a quick “hey” from an old friend, too. And I get that we are lucky to be enveloped in love and our relationships are bound by life, they still exist and will have existed.

These are all examples of little joys that actually aren’t little at all.

I’ve been thinking about it like fine chocolates. Many moments in a day are simply exquisite, like a morsel of well made chocolate. But even the finest chocolate can’t be noticed as exquisite if we just put it in our mouths, hurriedly, and just crunch-crunch-crunch, swallow and move on. And these little-but-actually-big joys are the same, even the most remarkable moments aren’t remarkable if we don’t savor them when we have them.

I know that bad moments happen. Sometimes, those moments are really horrific and truly terrible. But I want to also know in my bones and muscle tissues that bad moments don’t imply bad days. Bad moments can imply hard days, sad days, angry days, or even days of hopelessness and despair. But that doesn’t have to be bad.

And all this said, I know my days could be orders of magnitude harder if we weren’t as healthy, wealthy, or loved as we are. With temporal distance, even the hardest days of my life so far, like when I’ve done things that hurt others or the day I had to let my father go ahead without me, weren’t bad. They were unbearably hard, but I don’t have to think of them as bad, as if I wanted them to be wiped from existence.

Because if those days were wiped from existence, it’s one less day with all the good moments a day can have - even if those good moments are hidden in plain sight, waiting for us to notice them. If even one of those days were wiped from existence, I couldn’t have lived them.

And one definition of injustice to me is when there are people on this earth that have so many bad things happen to them that all the little things that can make a day good, even for a moment, remain hidden in plain sight. That they have so many struggles, and so much unbearable pain and disappointment that they aren’t capable of noticing even one good moment that day, even something as simple as the goodness of waking up from sleep or breathing.

I want my mind, my body, and my heart to understand what my soul already does: that good days don’t have to do with the trappings of how “lucky”, “blessed”, or “privileged” I am. That the “good” in a good day in life comes just from living. I want all of me to understand what my soul already does, that every day is a good day and every single one of those days matters.

Clear, shared, expectations: in projects and parenting

My wife made a brilliant parenting move this week.

Our older son is 3, and we’re trying to work on table manners with him. At least 5 days a week we have been getting into some sort of tussle with him over playing with his food, chewing with his mouth open, or deliberately making a mess. Mealtime has been the most common trigger of friction between us all.

And the other day I asked Robyn what she wanted to do, and she calmly replied, “I have a plan.”

What she did was simple and immediately effective. When we were serving the next meal, she set expectations for our son as she was putting down his plate. “The expectation is that we eat Cheerios with a spoon, blueberries you can eat with your hands.” And on she went about sitting down properly and what can be dipped and what cannot.

Her plan of setting clear expectations, in advance, worked immediately. It was a master stroke.

—

My work colleagues and I have been experimenting with approaches to clarify expectations, too. Instead of doing a weekly check-in with a traditional project board, we made a “why-what-how” board.

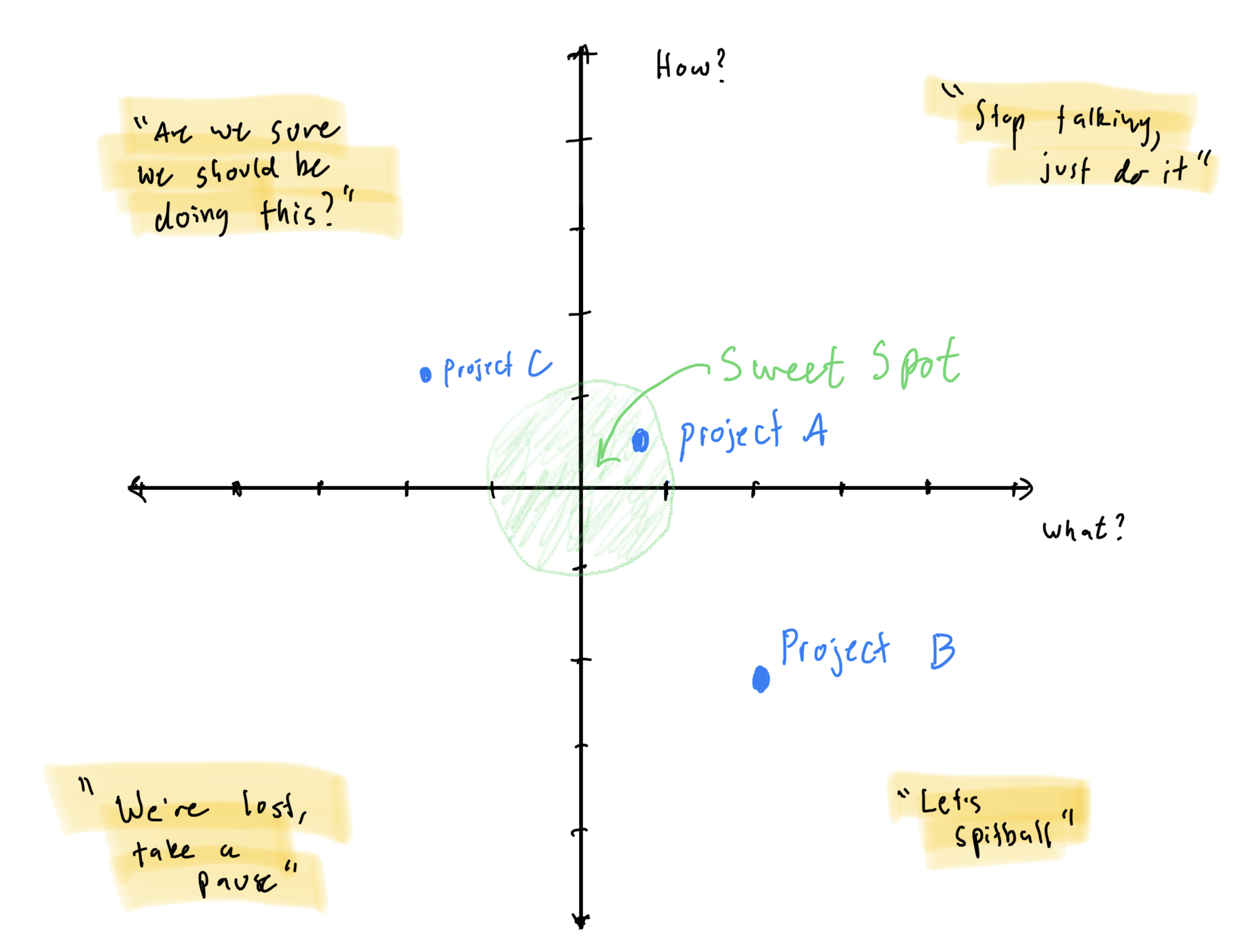

Here’s a representation of what our board (which is just a slide in PowerPoint) looks like:

What we do each week is re-score and re-plot our projects on this chart together. The goal of this exercise is to ensure the project is in the sweet spot of clear, shared, expectations.

The x-axis is the what. We make sure we understand what the intended outcome of the project is. Do we understand the deliverables? Do we understand what success looks like and what result we are trying to create? If the value is left of the origin it means the what isn’t clear enough. If the value is to the right of the origin, it means we are over analyzing the intended outcome and/or talking about it more than we need to.

The y-axis is the how. We make sure we understand the steps we need to take to achieve the intended outcome of the project. Do we understand the major milestones and next steps? Do we have a plan for how we’ll actually get the deliverables and analyses done? Do we understand the roadblocks ahead? If the value is below the origin, it means the how isn’t clear enough. If the value is above the origin, it means we’re micromanaging the project or getting too prescriptive about how it should be done.

We ask ourselves each week, usually during our Monday morning check-in, where are we at for each project. If we’re outside of the sweet spot, we spend some time clarifying the what, the how, or both.

Each quadrant, conveniently, has a nicely fitting heuristic which gives us a nudge on how to get back to the sweet spot:

High how, high what: we are talking too much. Let’s just take action.

Low how, high what: we understand what we’re trying to accomplish, but need to talk about how we get there. Let’s spitball and figure it out.

Low how, low what: we’re totally lost. We need to take a pause, reset and understand everything clearly where we are. This is the quadrant where the project is at risk and we have to dig out immediately.

High how, low what: this is the we might be wasting our time quadrant. If we don’t know what we’re trying to accomplish, even if we nail the project tactically, are we even solving the correct problem? We need to clarify the what (usually by escalating to the sponsor) or end the project.

What’s not plotted on the graph, but in the data table that powers the graph, are a few other elements: the why and who and the immediate next step.

The why and who has been a recent addition to our board, that we added a few weeks after trying this out for the first time. This value is the motivation for the project. Why does it matter, who is it for, what positive impact is this project in service of, why should anyone care about it? We think about our who as one of four general parties, that are applicable, honestly, to any organization. Any project has to ultimately impact at least one of these stakeholders in a big way to have a compelling why:

Our customer

Our owners or shareholders

Our colleagues

Our society or the communities in which we operate

If we can’t think of a compelling reason why what we’re doing matters to at least one of these four stakeholders, why are we even working on this project? We push ourselves to understand why, for our own motivation and to ensure we’re not doing something that doesn’t actually matter.

We also ensure everyone knows what the immediate next step is. If that’s not clear we establish it right there so there’s no reason we can’t take action right after our meeting.

Our team only started experimenting with this since the beginning of the year, but I’ve been finding it to be much more helpful than a traditional project board where the conversation revolves around the ambiguous concept of “status” and “accountability”.

Instead of checking our “status” non-specifically, and being reactive to a project that is “off-track”, we ensure that everyone on the team has clear, shared, expectations on each project, and we chip away at getting into the sweet spot of clarity on a weekly basis. By using this approach, we end up teasing out problems before they become large. Because after all, how often do projects get off-track if the why, what, and how of the project are clear to everyone, all the time? Rarely.

This approach is also much less autocratic than a traditional project board. Instead of the “manager” being dictatorial and projecting authority, this process feels much more democratic and equal, relatively at least. We all are working through the why, what, and the how together and even though one of us on the team is the titular “manager”, it feels more like we’re all on equal footing.

This is a good thing because everyone is more able to speak up, ask questions freely, and bring their talents forward to benefit the team and the people we’re serving. It’s less of an exercise where everyone is afraid of not having hit their milestones and therefore trying to tap dance around the status of the project.

There is of course a time and place for “status” and “accountability”. Of course, deadlines and results matter and we have to hit those. But what I’ve found so far is that by having clear, shared, expectations we are in a perpetual state of forward motion. We hit our deadlines as a natural consequence of having clarity. As is often said, but no less true, an ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure.

As is usually the case, what my wife and I are learning as parents is incredibly relevant to what we are learning about management and leadership. In this case the lesson is simple: clear, shared, expectations lead to better results (and less strife).

Paying Struggle Forward

I torture myself when a mission is going badly. Let’s say it’s a difficult project at work that I’m responsible for.

In the night, as I’m trying to fall asleep, I imagine myself in the CEO’s office, getting reprimanded, in front of my whole team. I feel the burn of my colleagues’ fearful, nauseated glances. I think about what I’m going to tell my wife, with a tail-between-legs posture, feeling like I embarrassed our family.

And when torturing myself in this self-imposed thought experiment, the bosses voice echoes enough to rattle my jaw. In my head I’m thinking, how did this happen, what was I thinking, why does this have to happen to me, why does it always have to be so hard?

But this week, in this particular version of my irrational thought experiment, the CEO asks me a question he never has:

“Why shouldn’t I fire you?”

And now, in a moment of clarity, I snap out of this hazy daydream. The answer is so clear to me. The boss shouldn’t fire me, because the next time we’re in this bad situation I won’t get beat. I’ve learned something.

Bad situations - whether it’s tough projects, losing a loved one, a failed relationship, an addiction, trauma, entrepreneurship, writing a book, climbing a mountain, you name it - are like viruses to me. They knock me on my ass. Sometimes, like viruses, bad situations quite literally make me ill.

But just as bad situations are like a virus, learning from our mistakes is like an immune response. Once we get through it, we’ve learned something. We’ve developed a sort of immuno-defense any time this particular bad situation comes up in the future. And I can share those anti-bodies with others.

The imaginary CEO shouldn’t fire me, I think in my head, because I now know a little bit about how to survive this bad situation, and I can tell the others how, too.

But that means I have to put this bad situation under a microscope and study it. I have to learn from it. I have to learn it well enough to teach others and then I have to actually teach others. Which means I have to tell the story of my struggle and failure again and again.

But reframing this into a process of learning from mistakes and teaching others makes the struggle feel meaningful. When I share what I’ve learned, I’m giving someone else a line of defense against this type of bad situation. They may not have to endure the same struggle as I did. And that is gratifying.

This was a mindset shift for me. In the past, when I’ve had bad situations happen, particularly at work, I’d just struggle. And I’d get angry. And I’d pout. And I’d just live with the struggle in a chronic condition sort of way for a long time. And I’d live in fear of the CEO’s office, or whoever the boss happened to be, until I had a new success to share.

I’ve had that utterly destructive thought of, why does life always have to be so hard, so many times, in so many types of bad situations. Like when my father died. Or when I choked on standardized tests. Or when I’ve had my heart broken. Or when I’ve been way over my head at work. Or when I’ve been up with a newborn that won’t sleep, for weeks at a time. Or when we’ve lived through a global pandemic. Or whatever.

But now I think there’s an opportunity to think differently. All these struggles are terrible, yes. But they don’t have to be in vain. They can be teachable moments, for me yes, but more importantly for others. I - and not just me, we - can give others some level of immunity from the deleterious effects of these bad situations that happen to us. But only if we’re wiling to share what we learn, humbly and specifically.

The option of paying our struggles forward to our children, our friends and families, our colleagues, and our neighbors seems much better than just living through them and forgetting about them.

Common bonds and unity that endures

The Hindu priest that married Robyn and I - to be clear, we were married twice: once by a Catholic priest, once by a Hindu pandit - left us with simple advice that we still remember and recite often:

From now on, you must be Together, Together, Together. Remember, Together, Together, Together.

From that day, Robyn and I were united in marriage.

But to be honest, I usually find myself wanting more when I hear the word “unity” uttered. Unity, to me, is a hollow word unless the common bond it invokes is specific and salient. Unity for what? Around what purpose? For whom? Unity bound by what beliefs?

In our marriage, and in the marriages of the people that we are close enough to see their marriages up close, I would say the beliefs that bind them are specific and salient. Here are some examples from our marriage:

Our vows: to love, honor, and cherish each other; for better or worse; for richer or for poorer, in sickness and in health, good times and in bad, until death do us part

Our common beliefs: belief in God; that we put family first, but that our marriage ultimately exists to serve others

Our common dreams: to grow old together, to grow a family and stay close to our international extended family, raise our children to be good people, to learn through travel, and be enmeshed in a community throughout our life

Our common experiences: the trips we’ve taken; the dates we’ve been on; the time we’ve spent doing nothing but enjoying each other’s company; the suffering we’ve navigated together; the little moments every day where we affirm, support, respect, and acknowledge each other and the investment of love all those moments - big and small - represent

If you’re a married person ( or expect you will someday) I do suggest trying to do a similar exercise where you specifically write down what the common bond that undergirds the unity you have with your spouse. I honestly had never done this until just now and I feel washed over with warmth, confidence, stability, and love.

I think this exercise is worth doing for more than just marriages. Any team or community that wants to endure also requires a durable common bond that is specific and salient. Asking the question “what unites us?” is just as relevant to companies, communities, and even states or nations.

The real hum-dinging implication, though, is how. How do we discover and articulate our common bonds? How do we create and nurture our common bonds? It’s not useful to merely describe that we need common bonds to have unity - that’s obvious. The very difficult question is how.

I’m planning a few posts over the next 4-6 weeks that push this idea of unity and the “how” of it further. But here’s a start: I think a good place to begin is interrogating our own beliefs, and asking what do I believe?

There was a terrific series some years ago that National Public Radio launched called This I Believe. The premise was simple: ask people to articulate their most core beliefs and then share them publicly. And when you hear some of those essays, you don’t just understand others’ beliefs cognitively, you feel and internalize them. We could all stand to write one of those essays and share it with the people we are close to.

Because after we understand our own beliefs, our next job - and I think it’s the harder and more important one - is to listen and deeply understand, feel, and internalize the beliefs of others.

And from there, we are well on our way to articulating our common bonds specifically and saliently - and developing a unity that is durable and enduring.

The One-way Door

At some point in the past five years, I accepted that the door Papa went through went one way.

It’s been five years since Papa went through the door.

In five years, a lot of life - our marriage, Riley, buying a home, changing jobs, a trip to India, a trip to Frankenmuth, family dinners and washed dishes, backyard barbecues and park walks, Bo’s whole life, Myles’s whole life, 5 Diwalis, 5 Thanksgivings, 5 Christmases, the Trump Presidency, a pandemic, two half marathons, knowing God again, a mostly written book, and many many moments of laughter and tears - has happened.

And for a long time, I knew he had already left. But, still, I thought he might come back through that door. Not in a real way, but in a fantasy sort of way. Like, in a waking up from a dream or being on candid camera sort of way. For a long time, a little part of me was holding onto the only-with-a-miracle possibility that he’d be back.

I don’t know exactly when, but sometime in the past five years I let go of that hope. I knew and thought he wouldn’t be coming back. Finally, I accepted that it was a one-way door.

And so what to do? It is true, the door is one way. And one day, I too, will head through it. That is certain. This is all certain.

Basically all of us have this predicament at some point in our lives. We have to accept that it’s a one way door, and choose what happens next. Do we sit and wait in a chair by the door, biding our time until our turn comes? And then, relief, because we have rejoined our loved ones who have already gone ahead?

Or, do we build a life on this side of the one-way door? Do we make memories and hang those pictures up beside it? Or cover the door in crayon drawings and finger paint? Do we build a table and cook and feast to celebrate life on this side of the door? Do we laugh and cry and yawp and run and play and blush and garden and read and mend things?

I feel guilty, often, for trying to build a life without him on this side of the door. Even though I know it’s not betrayal, I think it is. I know living life is what he would make me promise to do had he known he was going, but I still think something’s not right about it. I may never rid myself of this dissonance. I don’t know.

But the door no longer haunts me, on an hourly and daily basis like it used to. It’s pain that’s chronic and manageable, not acute and insufferable. But here I still am, five years later, torturing myself by reliving memories of his last days, while weeping tears of gratitude for the life we have now. And still, thinking of him, praying, and wondering how he is on the other side of the door.

The Weekly Coaching Conversation

Coaching others is definitely the most important and rewarding part of my job. When I took on this responsibility, I worried: would I waste my colleagues’ talent? How do I help them grow consistently and quickly?

Here’s a summary of what I‘ve been experimenting with.

Experiment 1: Dedicate 30 minutes to coaching every week

I raided my father-in-law’s collection of old business books and grabbed one called The Weekly Coaching Conversation: A Business Fable About Taking Your Game and Your Team to the Next Level.

The idea in it is simple: schedule a dedicated block of 30 minutes every week with each person you’re responsible for coaching. I thought it was worth trying. As it turns out, it was. Providing support, feedback, and advice falls by the wayside if it’s not part of the weekly calendar - at least for me.

Experiment 2: Ask Direct Questions

We start each 30 minute weekly meeting the same way, with a version of these two questions:

On a scale of 1-100 how much of your talent did we utilize vs. waste this week?

This question is useful because it’s direct feedback from the person I’m trying to coach. I can get a sense of what they need. Most of the time, what is holding them back is either me, or something I can support them with, such as: more clarity on the mission, an introduction to a subject-matter expert, some time to spitball ideas, or just some space to explore. This is also a helpful question to ask, because when the person I’m coaching is excited and thriving, I get to ask them why, and do more of it.

What’s one way you’re better than the person you were last week?

This question is useful because it helps make on-the-job learning more explicit and concrete. We get to unpack results and really see tangible progress. Additionally, I get a sense of what the person I’m coaching cares about getting better at which allows me to tailor how I coach them.

Experiment 3: Stop controlling the agenda

At the beginning, I would suggest an agenda for our weekly coaching sessions. But over the course of 3-5 weeks, I transitioned responsibility for setting the agenda to the person I’m coaching. This works out better because we end up focusing our time on what matters to them, rather than what I think matters to them (which is good, because I’m usually wrong about what matters to them).

It also works out well because my colleagues are in the driver’s seat for their own development. And that fosters intrinsic motivation for them, which is really important for fueling real growth. I certainly raise issues if I see them, but it frees up my headspace and my time to be responsive to what they ask of me.

I still have a lot of improvement to do here, but I spend a lot less time talking and much more time asking questions and being a sounding board by letting go of control of the agenda. Which seems to work out better for my colleagues’ growth.

What I’m thinking about now (I haven’t figured it out) how do I know that my support is actually working, and leading to real growth and development?

—

I am absolutely determined to discover ways to stop wasting talent, in my immediate surroundings and across the organizational world. It’s a moral issue for me. And I figure a world with less wasted talent starts with me wasting less talent.

I’ll continue to share reflections on what I’m experimenting with so all of us that care about unlocking the potential of people and teams have an excuse to find and talk to each other.

Radical Questions, Radical Diversity

By asking questions on facebook, I’ve learned the value of radical diversity and radical questions.

Over the holiday, my father-in-law asked me a very interesting question along these lines: after asking questions on facebook for so long, what have you learned?

Over these past five years or so of asking an almost-daily questions, I’ve tried not to ask gimmicky or empirical questions. I’ve tried to ask simple, specific questions that require reflection and emotional labor. This is not for any special reason, I just I think those sorts of questions are most interesting and yield the most wisdom on how to live a good life and be a good person.

What has been surprising is how often someone says something incredibly perceptive and relevant. Like, nearly every response I’ve ever received to any questions I’ve ever asked is something valuable. Individually, everyone has something profound to contribute.

At the same time, I’ve come to realize how deep but narrow of an understanding each of us have about the human experience. Nobody’s perspective fully explains or grasps the full truth on how to live a good life or be a good person. We all have a fragments of it. We all have a remarkably clear understanding on the little piece that’s been made clear to us by virtue of our most unique and compelling experiences.

If the truth of life were a large tree, we are not photographers standing from afar that can see the whole tree. Rather, we are each little birds that understand just the leaves and branches right around us.

Which leads me to two big takeaways - to understand the big truths of our human experience we need radical diversity and radical questions in our lives.

RADICAL DIVERSITY

The importance of diversity in teams trying to solve complex problems is not a new idea. Scott E. Page (Go Blue!) has done fascinating research in this area. I loved his book on the topic, The Difference: How the Power of Diversity Creates Better Groups, Firms, Schools, and Societies.

But what I would say, is that diversity isn’t just important for team problem solving. To understand the tree of human experience we need radical diversity in our live so that we can learn about the far reaching parts of the tree we’re all in, so to speak. Like, we don’t just need to learn from people who are different from us, they need to be radically different, from branches on the tree that are far, far away from us.

For example, there’s just some things that drug addicts understand better than others. Straight up. Or people who have lost parents early in life. Or people who have been bullied. Or people who have been insanely wealthy or dirt poor. Or people who have lived abroad. Or people who’ve had to execute massive projects. Or people who’ve studied the arts. Or people who have built things with their hands. Or people who have been abused. Or people who have raised children. Or people who have lied or have been lied to. Or people who have been to space. Or people who have served the most vulnerable. Or people who grew up in most typical suburbs. Or people who have been farmers. Or people who have committed heinous crimes and returned from prison.

Or whatever radical experience it is. There are just some things that folks who have had certain kinds of radical, intense experiences just understand better than I do. To really understand the human experience, I can’t settle for knowing people who are different than me - I have to learn from people who are radically different than me.

RADICAL QUESTIONS

At the same time, I will not learn much about the human experience, even if I have radical diversity in my life, if I only talk to those people about topics like the weather, sports, politics, or celebrity gossip.

To learn about human experience we have to talk about the radical things that have happened to us, which means we have to ask radical questions.

I don’t claim to be great at this yet, but I have learned a lot on how to ask good questions. And radical doesn’t mean sensational. It means questions that are reflective and require emotional labor.

And yes, I’d suggest that those sorts of questions are indeed radical. Because honestly, the bar on asking radical questions is really low. Even though the questions I tend to ask aren’t extremely radical most of the time, it’s easy to clear a very low bar.

Most questions that we’re ever asked in our day to day lives are boring and sanitized. Think about every customer feedback survey you’ve ever taken: boring. Think about every question asked during a panel discussion you’ve attend: boring or loaded with assumptions. Think about every question you’ve ever talked about chit chatting at a bar or waiting in line somewhere: boring or safe.

There are so few forums where we ask or are asked questions that require reflection or emotional labor. And so, all we ever learn about is our little twig on the tree of human experience, even if we’re surrounded by radical diversity.

And I’d also say that it’s not that scary to ask a radical question, though it may feel that way. If you haven’t, you should try it sometime.

We are so deprived of radical questions in our lives, I’ve found that many people seem to feel liberated when asked a radical question. We’re just waiting for the opportunity to share something radical, if we believe we are listened to, safe, and respected.

Radical listening and radical love in settings of radical diversity lead to radical answers to radical questions.

I think most people, at least my age, care about this wisdom of how to live a good life and be a good life. We can help each other do this. We really can.

Debrief questions for parents (and coaches)

We can’t “teach” our kids character, but we can debrief it.

I have been struggling for a long time thinking about how to teach our sons “character.” They won’t learn it from a book, nor will sending them to Catholic school magically make that happen.

What dawned on me this week, is that I can debrief with them. And really do that intentionally.

I attended a wonderful summer camp in high school, it was “student council camp.” And there were lots of character building-activities, that I still remember and think about often.

When I become a camp counselor, I had the opportunity to facilitate those character-building activities. And what we always said amongst other counselors is that it’s not the activity that teaches anything, “it’s all about the debrief.”

Debriefing - the process of helping others learn from their own experiences - is a hard-earned skill. It’s not easy. But it’s essentially all about asking the sequence of questions that highlight the salient information which lead to a a novel insight.

During a debrief, the goal isn’t to tell anyone anything, the goal is to nudge them along by bringing relevant facts to the debriefee’s attention which causes them to have an “aha moment”. In those aha moments, so to speak, they learn a lesson on their own. Good debriefers don’t teach, they help others teach themselves.

Cutting to the chase, I started putting a list of questions that could be used to debrief, even with young children. I needed to write them down to debrief myself I suppose.

I share that list here in case it’s useful to those of us that are parents or coaches. I also share it here in hopes that others share their own debrief questions. If you’re uncomfortable leaving a comment, please do contact me if you have a thought to share, I’d be happy to append it anonymously.

Debrief Questions for Parents and Coaches

How do you feel right now?

Are you okay?

Can you tell me exactly what happened?

Then what happened?

What were you thinking right before you did X?

How do you think this made [Name] feel?

What can you do to make this right?

Why didn’t X, Y, or Z happen instead?

What were you trying to do by doing X?

What could you have done instead of X?

Was doing X okay, or not okay? Why?

What else happened because you did X?

Do you have any questions for me?

What are you going to do differently next time?

What happens next, right now?

Reflection Questions: NYE 2020

Some questions in support of your 2020 holiday reflections.

Robyn and I (and our families) relish the last week of the year as a time to reflect on the year past and upcoming.

Here are a few reflection questions, many that we’ve talked about in our household over the past week. I wanted to share them, since this year in particular warrants reflection and prompts can be helpful.

But whether or not you use these prompts, I do think reflection - whether alone, with a friend, a partner, or a notebook - during this time of year is well worth it. I highly recommend taking at least a few quiet, contemplative minutes before you return to your usual routine.

Happy New Year!

Reflections that look backward:

What have you received this year?

What have you given this year?

How have you made life difficult or inconvenient for others this year?

What did you intend for 2020, and what actually happened?

What were your high points and low points? What emotions did you feel at those points?

What do you now know about how the world works, that you didn’t before?

What happiness or sadness are you still holding onto?

In what ways is your relationship different, or stronger?

How has your perception of life in your community changed this year? How has your view of the world changed?

What activities or people did you find a way to hang onto in some form?

What’s an event that you’d want your grandchildren to remember about this year? What lesson would you share with them?

Reflections that look forward:

What about this year would you continue in the future?

What about this year would you never opt to do again?

What do you intend for 2021?

How do you want to make your closest relationships, like your marriage, stronger in 2021?

What outcome that you want to happen is at the top of your list for 2021?

What’s a way that you want to behave differently in 2021?

What’s something you want to spend more time on in 2021? Less time on?

What phase of life are you transitioning into or out of?

What hard thing do you intend to tackle in 2021, even though you may fail?

What are some of the relationships you want to focus on in 2021?

What’s something that seems urgent but is really just a distraction for your most important 2021 priorities? (Pair with this post on anti-priorities).

Kitchen Table Entrepreneurship

We get up off the mat if and when something really, truly matters.

I have been trying my damndest this year to not give into the “that’s 2020” mentality. This whole year, I’ve been operating with a mantra of “get up off the mat, get up off the mat, get up off the mat.”

And let me start with honesty: I’ve failed on many fronts.

I didn’t finish this book, I shouted a lot at my sons, and attended church less, even though it was easier than before - to name a few ways I’ve failed.

But I’m encouraged. At the beginning of the year, I thought basically everyone but me had given up on 2020, as if it made you one of the cool kids to talk about how much 2020 sucked.

But this week, after taking a breath, it hit me how many people hadn’t given up on 2020, and were just going about their lives, quietly, but with tremendous courage and persistence.

In retrospect, I’ve seen an explosion of what I’d call “kitchen table entrepreneurship.”

By this, I don’t mean the venture-backed startups that develop software or some lifestyle product. Though I’m sure that’s continued.

I mean the ideas that were born around kitchen tables, in WhatsApp threads, or on Zoom calls by regular folks just trying to find a way to make things better for the people around them.

Like my sister-in-law who proclaimed it to be “Pajama Christmas” this year, rolled with three onsies to our family get together, and found a way for us to do a family social-distanced wine tasting after virtual church, complete with tasting scorecards to make up for the fact we couldn’t safely do our normal traditions.

Or the public servants in Detroit who just figured out how to rapidly build out drive-through Covid testing within days and weeks of the pandemic starting, put in protocols almost literally overnight to prevent the spread of Covid within DPD and DFD, launched a virtual concert of Detroit artists to help people stay sane, or delivered thousands of laptops to schoolchildren that didn’t have remote learning capabilities.

Or my wife, who’s been charging with some of her colleagues on legit, sincere Diversity and Inclusion programs and a Caregiver support group. She’s too humble to make noise about it, but she and her colleagues are doing really innovative work to change their particular workplace and improving the lives of their colleagues.

Or there are so many people who have figured out how to get their elderly neighbors groceries, or shovel their sidewalks, or get things like neighborhood storm drain cleanings coordinated even though some folks in the neighborhood barely knew how to send an email before this thing started, let alone join a Zoom call.

Or just today, I was able to use my Meijer App like a mobile cash register to scan my items as I shopped - minimizing time in the store and contacts with frontline employees.

Or our local businesses on Livernois, just turning on a dime to find ways to stay in business and operate safely. Narrow Way, our local coffee shop, is really efficient now, has used technology and new offerings to make their customer experience even better than it was before, and even though I’ve been in a mask, they still found a way to know me by name and make me feel respected and welcomed.

And even people who’ve had relative after relative get sick or pass away - I’ve heard so many stories of how they’re finding ways to get through, or continue to help others, or just keep doing what they do.

These are just examples from my own life, but they seem to be illustrative examples of people just making things better where they are, without a lot of money or a lot of fanfare. They’re just doing it.

Maybe this has always been happening and I haven’t noticed it as much. Either way, I think this kitchen table entrepreneurship is worth celebrating.

As I’ve reflected on these stories of kitchen table entrepreneurship, there has been one lesson that’s struck me most.

During this year, the entrepreneurship I’ve seen has all been on things that are important. Like, I haven’t seen stupid or totally self-indulgent or narcissistic apps, products, and services emerge from this situation. Those are getting less buzz at least.

The kitchen table entrepreneurship I’ve seen has addressed problems that matter. People are finding ways to make things better in material ways for the people around them. They’re not doing this stuff to get a pat on the back, get in the paper, or hustle someone out of a dollar. They’re doing it because it matters for the people around them: their families, friends, employees, neighbors, and customers.

And the lesson for me has been relearning a simple but wise idea: focus on what matters. That’s when hard stuff gets done, and new ideas emerge from unlikely places - when the outcome matters.

In that expression - focus on what matters - I’ve always leaned into the focus part. If I just focus more, I can live out my intentions, I thought.

But I’ve learned this year, that it might be wiser to lean in the the “what matters” part of that expression. Is what we’re trying to do really, really important? If not, why are we even doing it?

The lesson of kitchen table entrepreneurship, for me at least, has been to dig deeper for why something matters. If we can find things that matter, the focus part seems to mostly take care of itself.

Seeing all this entrepreneurial activity emerge from kitchen tables all across the country has been truly inspiring to me. And more importantly, it has been a great reminder that we get up off the mat if and when something truly matters.

Finding peace with the starved twenties

My twenties were starved, not lonely.

I noticed something odd this week.

Most of my dreams, which are unfortunately always stressful, take place in my early to mid twenties. I don’t think I’ve dreamt about my kids, maybe ever. I hadn’t noticed the pattern until a few days ago.

Why oh why would my twenties be hiding and lurking in my mind?

Upon reflection, my twenties were a lot like this year. I went days, sometimes weeks, without giving a hug because I traveled for work and rolled by myself most of the time. I had fun hanging out with friends at the bar every weekend, but that rarely led to conversations requiring emotional intimacy.

I always thought my twenties were lonely. And they were, but they were more than that. They were starved. Not of nourishment, but of emotion and spiritual depth. And love.

Upon reflection, my twenties were a lot like this year.

It struck me though that lots of people have to live like it’s 2020, but every year. Can you imagine?

I think it was enough to just see the past clearly and more honestly. The moment I connected the dots, and understood the difference between alone and starved I seriously felt it in my abdomen, right below my sternum; a tension released.

Two nights later I had a dream, and my sons were in it. Imagine that.

Damn it, let's give our kids a shot at choosing exploration

I dreamed of exploring space, but the problems of earth got in the way of that. I hope our kids can truly choose between exploration and institutional reform.

In retrospect, this isn’t the vocation I was supposed to have. It was put on me, or at least started, by an act of God. But my path within the universe of organizations - a mix of strategy, management, public service, and innovation - was never supposed to happen.

I had always, in my heart of hearts, set my mind on space. I knew I would probably never be an astronaut. For a multitude of reasons I would’ve never had a path to the launchpad - being an Air Force pilot or bench scientist wasn’t me. I won a scholarship to Space Camp when I was in 4th grade and I got to be the Flight Director for one of our missions. And from then on, I dreamed of being on a team that reached outward and put a fingerprint on the heavens.

Five years later, a mosquito was never supposed to bite my brother Nakul -when I was 13 - thousands of miles away in India. That mosquito was never supposed to give him Dengue Fever. He was never supposed to be patient zero of the local outbreak and die from it. None of that was ever supposed to happen, but it did.

And, when he died, I got hung up on something. I didn’t get caught up on curing the illness itself. I didn’t feel called to become a biologist, epidemiologist, or a physician. What I couldn’t for the life of me understand is how in the 20th century, with all its wealth and medical progress, could Nakul not receive the treatment - which humankind had the capability to administer, by the way - he needed to survive Dengue Fever? How was Dengue Fever still a thing, in the first place? How could governments and health care systems not have figured this shit out already?

The problem, as I saw it then, was institutions. His death, and millions of others across the world, could be prevented with institutions that worked better. And the vocation that called out to me shifted, and here I am.

—

Watching kids watch Christmas movies is interesting. You can see their body language, facial expressions and language react to the imagination and wonder they’re observing. Their bodies seem like they’re preparing to explore, just like their minds are. They light up, appropriately enough, like Christmas lights. It’s really something to see a child imagining.

For our boys, right now, anything in the world is possible. Any vocation is on the table for them. They can dream of exploring. They can dream of applied imagination. They can dream of storytelling and art. They can dream of so much. At this age, I think they’re supposed to.

What occurred to me, while watching them watch Christmas movies, is that I don’t want them to be drawn into the muck like I was.

I was supposed to be exploring space, but plans changed and now I’m firmly planted on earth, in the universe of human organizations. I am definitely not charting new territory, rather, I’m fixing organizations that should never have been broken in the first place. I am not an explorer, I am a reformer. There was no choice for me, the need for reform here on earth was too compelling for me to contemplate anything else.

But for our children, mine and yours too, let’s give them a choice. Let’s figure out why our institutions seem to be broken and do something different. Let’s figure out why our social systems seem to be broken and do something different. Let’s not let institutions be a compelling problem anymore. Let’s take that problem off the table for them. Let’s complete this job of reform - both of our organizations and our individual character - so they don’t have to.

Maybe some of our children will want to follow in our footsteps and be reformers, but damn it, let’s give them a chance at choosing exploration instead.

I hope our kids are not happy, but rather happy enough

Please, God, let our children’s suffering be graceful instead of senseless.

I think there’s a shift happening with Millennials that is still mostly invisible. It’s in how we’re raising our children. Maybe it’s just me, but I don’t think so.

My parents, aunts, and uncles had a similar sentiment when they described what they wanted for us kids. They wanted us to be happy. Since having our two sons, I’ve come to realize I don’t want that. I don’t want them to be happy. I want them to be happy enough.

Yes, I do want our kids be comfortable, safe, healthy, respected, and be able to enjoy some amount of luxury in their lives. But there was a time in my twenties where I had those things, and not only was I miserable, it was a waste.

Yes, when I was a young adult, I had a well-paid, high-status job. It afforded me a comfortable, secure, lifestyle and a lot of fun nights out at the pub. I exercised a lot. I had time to do whatever I wanted. So I was indeed happy.

But it turned out not to be the life I wanted. Every year since my father passed, my life has become harder. Like, every single year Robyn and I think it can’t get any more intense, and then it does. We’ve come to expect more pain, so to speak, with each passing year.

But even though life is more painful, difficult, demanding, frustrating, exhausting, and less “happy”, it’s somehow better. It’s because we’re having to make sacrifices - for our children, pup, family, friends, neighbors, colleagues, and clients. All this suffering brings something, but I wouldn’t call it happiness, and it’s not even always a feeling of joy. It’s something that I prefer to happiness, but I don’t know what the word for it is.

Now of course, this situation would not be possible if we were starving, depressed, ill, wounded, freezing, wet, or alone. So to have a shot at this graceful suffering, we have to avoid the senseless stuff. We have to be comfortable enough. Safe enough, healthy enough, respected enough, content enough. Happy enough. Senseless suffering makes graceful suffering impossible.

Please, God, let our children’s suffering be graceful instead of senseless.

But I see the allure of wishing “happiness” upon our children. Seeing our kids unhappy - sick, despondent, or in unrelenting pain - is torturous to me. Literally, the best way for someone to torture me would be to hurt my children. Honestly, I am on the edge of weeping when one of ours just has “tummy troubles”. And so the sentiment of a person wanting their kids to be happy makes sense to me, because it’s a way to avoid torture.

At the same time, I’ve lived a life of “happiness” and comfort, and I didn’t want it. I don’t think our kids will want that, either. So I pray for them to not be happy, but happy enough. Maybe I’m the only one who feels this way, but I think it’s possible that I’m not.

What am I doing with my surplus?

I am grateful or a lot this Thanksgiving. But what am I doing for others?

My feelings about "privilege" are complicated.

On the one hand, the data is clear that certain factors that we are born into - like race, gender, sexual orientation, zip code, etc. - are predictive of how healthy, wealthy, and at peace we become.

On the other hand, those with "privilege" still have to avoid screwing up the privilege they have to become healthy, wealthy, and at peace. And that's not trivial, either.

On the other hand, privilege is used as leverage to exploit those with less money and power. That exploitation is wrong.

On the other hand, I can't and don't want to live in a perpetual state of guilt, apology, doubt, and shame about any "privilege" I have. I didn't choose to be born into privilege or non-privilege, just like everybody else.

So what do I do with these complicated feelings?

It seems just as wrong to skewer people with privilege as it is to suggest privilege is a conspiracy. And having some sort of atonement about privilege through acknowledgement or "checking" privilege seems okay, I guess. But I honestly don't know the material, sustained effects it has on our culture. It doesn't seem like enough to simply become aware of privilege.

I've been thinking about this idea of "privilege" lately because of Thanksgiving. I feel extremely lucky to have steady work, work that doesn't require leaving my house, and health insurance. I have a family that I love and loves me back. I have friends and neighbors that I love, and love me back. When people have asked me, "what are you grateful for this Thanksgiving?" these are the things I've talked about.

Talking with and listening to my brother-in-law on Thanksgiving, inspired a different path.

It was helpful to replace the world privilege with "surplus". I have a lot of surplus. I was born into a life of surplus. There are other people who were also born into a life of surplus.

Nobody chooses what surplus they were born into.

But everybody chooses what they do with the surplus they have.

What am I doing with my surplus?

Am I trying to get more? Am I trying to shame others because they have more surplus? Am I trying to reallocate surplus after the fact? Am I trying to convince myself that I deserve the surplus I have? Am I using my surplus to enrich my own life and that of my friends and family with ostentatious luxuries? Am I wasting my surplus? Am I trying to acknowledge and atone for my surplus? Am I trying to stockplie it? Am I trying to bequeath it?

Or am I trying to use the surplus I have to enrich the lives of others?

I honestly don't know if this is the best answer on what to do with these complicated feelings about privilege. And maybe there doesn't have to be one "answer" in the first place.

But the best I can come up with is not worrying so much about privilege itself, and who has more of it than me. To me, it makes more sense to worry about whether I am enriching the lives of others.

"To who much is given, much is expected" is an old idea, but it seems like an enduring and worthwhile principle to apply to this befuddling idea of privilege.

Dreams, from joy and the conviction of their own souls

Why, exactly, did I have the dreams I ended up having?

Raking leaves is one of those chores I don’t want to do until I’m doing it.

Until I’m with rake in hand, I’ve forgotten the crispness and soft chill of the air, and the sound of the brushing leaves. It’s sweatshirt weather. But I also forget that sweatshirt weather is also “thinking weather.”

As I raked yesterday, I escaped to thinking about dreams. And my subconscious drew me not to thinking about what my dreams are, but rather, “what influenced me to have the particular dreams that I do?” And for me, so much of my dreams are wrapped up into my parents’ dreams for me.

To be a “big man” or a man of great community respect. And I wondered why they had those dreams for me, and I think it must have been, at least in part, because of how they were treated when they arrived in this country. As immigrants, I don’t imagine they ever felt accepted or welcomed, at least for the first few decades of their arrival.

And when you’re an “outsider” respect and wealth protects you from harm - whether that is rude service or dirty looks in public, or more unfortunately, a brick through your window. I imagine my parents’ pain is something that influenced me to want the dreams that I wanted early in life. Pain is a powerful influence.

But my dreams were also influenced by the broader culture whose collective opinion skews toward a hedonistic, lowest common denominator and accepted malaise . Let’s call those the dreams of “the herd”.

The herd wants me to hold its dreams as my own, because it’s a mechanism of justification. It’s harder to criticize the herds hedonistic aspirations if they convince me (and others) to be part of it. The more people the herd co-opts, the more their dreams - however dishonorable they may be - become normal. Just like pain, the herd is a powerful influence.

So early in life my dreams were influenced by two things, avoiding pain and succumbing to the herd’s mentality. That’s where “I want to be a Senator” or a “social entrepreneur” came from - those were two dreams that pain and the herd led me, specifically, to.

And I’ve let go of those dreams, not because I grew out of those dreams, but because I grew out of pain and the herd’s mentality. Mostly through luck and blessing, some very special friends and family helped me to discover joy and my own soul. It’s a journey less like climbing a mountain, and more like a long, lonely walk.

It’s a journey I am still on, but my dreams are now about a growing family, goodness, the honor of public service, and sacrifice for a community bigger than myself. I still fall into the traps laid before me by pain and the herd, I am after all a mortal man. But these dreams - borne of joy and what lies within the core of me - are a far cry from the version of myself that was nakedly ambitious, longing to be on the Crain’s 20 in their 20’s list.

Honestly though, the point isn’t about me, nor should it be.

The point is this: I can only hope - for our children, and the children of our friends, family, and neighbors - that the generation up next spends less of their life having their dreams influenced by pain and the herd than I did. I hope, deeply, that more of their dreams, and really their lives, are instead influenced by joy and the convictions of their own soul.

Preventing violence and madness, through abundance, strong institutions, and goodness

A theory on how to create a community that resolves conflict without violence and madness. It takes three supra-public goods: abundance, strong institutions, and goodness.

If we live in a community, rather than isolated in the woods fending for ourselves, conflict is inevitable. We are all imperfect humans, after all.

And in my mind that leads me to suggest one, bedrock aspiration that we all must have to live in a community: the conflicts we can’t avoid are settled without violence and a dissolution into madness.

But how?

To do that, I think we must create three supra-public goods: abundance, strong institutions, and goodness.

Abundance is important because it creates surplus. Surplus is important because it prevents us from squabbling over the fundamental resources we need to survive and have a life beyond mere subsistence. It also creates the space for generosity, culture, scholarship, art, and human flourishing.

Strong institutions are important because they create norms. Norms are important because they provide guardrails to ensure nobody behaves so peculiarly that they cause widespread and unbridled harm. Norms are also important because they provide accepted processes for mediating conflict when it inevitably happens.

Goodness is important because it creates trust. Trust is important because it prevents conflict in the first place. When people are good to each other, they give each other the benefit of the doubt and are more likely to let things slide or work out an issue, rather than skipping straight to punching their lights out. Trust is also nice because it reduces the need for concentrated bodies of power to enforce the norms laid out by institutions.

The big eureka moment for me is that we really need to grow in all three areas simultaneously. One or even two of this three-legged stool is enough.

A society without abundance is starving and fragile. A society without strong institutions can’t ever grow in size or manage the challenges of diversity. A society without goodness is lonely and without meaning.

To live in a society that resolves conflict without violence or dissolving into madness, these are the three things we - whether that “we” is us individually, our friends and families, or the formal organization we are part of - must all be trying to bring into the world: abundance, strong institutions, and goodness.

And again, we need all three. Not even two are enough to create a world where our children’s dreams are borne from joy and the convictions of their own souls, rather than from pain and our lesser-than-honorable impulses.

Every culture is misunderstood

Every culture is deeper or richer than we know.

Most people don’t understand the depth of Indian culture. For example…

Most people don't understand that there’s much more to Diwali than lighting pretty candles. Most people don't understand that there's more to yoga than it being a good "work out" with an emphasis on breathing and stretching. Most people don't understand that there are a LOT of Indians (and Indian-Americans) who don't work in medicine, IT, or engineering.

Most people don't know about the rich tradition of art, music, poetry, philosophy, theology, and governance on the Indian sub-continent. Most people don't understand that the range of our cuisine is so diverse and wide, that saying "I like Indian food" is similar to saying "I like ancestrally-white people food".

Our culture goes much deeper than the caricature that most other people believe it to be.

I assume that virtually any group feels similarly sometimes. The sentiment of "our culture and people aren't stupid, you just don't understand their depth" is not unique to people of any descent - Indian or otherwise.

But I've learned two things about this:

One, if I believe any culture or community is dumb, antiquated, or backwards - i probably don't understand that culture's depth.

And two, nobody is going to understand the depth of my culture - whether it's the culture of India, America, Michigan, Detroit, or even our family - unless I welcome them with open arms and share something beyond the caricature they already have in their mind.

Your Dada's American Dream

Your Dada came here for a better life, full of prosperity. Today is a special day because we no longer have to doubt that we belong here.

It is time I told you boys the story of how we came to America.

Your Dada was the first of our Indian family to arrive here, by way of Ottawa and Chicago. But similar to the histories of many immigrants, his story doesn't begin in North America, it begins on the shores of a distant land, halfway across the world.

Bombay is a city on the sea. I have never been there, but I have heard of its vista many times. Your Dada loved the sea, although I'm not sure whether he's always loved the water or if he began to love it because he moved to Bombay. Which is not where our family is from, by the way - we are not Mumbaikars, ancestrally - but it is where the tale of our family coming to America begins.

Your Dada was at university for engineering there. He was in a hallway, probably on his way to some class, and a forgotten piece of paper was strewn across the floor ahead of him. This paper, at least from the way he told me the story, made quite an impression on him. As it turns out, the paper was a list, of colleges and universities in the United States and Canada that offered scholarships for foreign students.

And the idea to leave India in search of a better life, was probably a seed in his head before this moment. But this forgotten piece of paper is what caused that seed to take root, strongly, in his mind.

Your Anil Dada was a longtime friend of my Papa. They went to school and college together. And Anil Dada once told me that Papa's nickname among his school friends was Ghoda. It's the hindi word for horse. And that's what your Dada was, a work horse. Once that paper came across his path, and that idea of a scholarship rooted in his mind, it was only a matter of time before he got here.

And despite your Dada facing extraordinarily difficult circumstances, here we are.

If you could ask him yourself about why he came here, as I have tried to, he'd tell you that he came here "for a better life." I've thought many years about what he meant. It's a haunting thing to wonder - about what drives your father - because it is after all, an inevitable part of what drives his sons.

When he said a better life, I think he meant prosperity. And part of that means wealth. But prosperity - in the way I think your Dada meant it, and the way I mean it here in this letter - is not only wealth. It is much more than that.

Prosperity is thriving. It is reaching the height of our potential as human beings. Prosperity is creating surplus, and then having the honor of spreading it humbly and generously to others. Prosperity is what’s beyond the essentials needed to have our physical bodies survive - it is the jewels of knowledge, culture, art, virtue, and the audacity to dream of a better life. For ourselves, yes, but more importantly for ourselves and others.

In America, prosperity is intervening to end a world war. It is vaccines and splicing the gene. It is going to the moon and brokering peace on earth. It is bringing children out of hunger and into love. It is the freedom to think beyond our daily bread and our tired and our poor. It is seeking to understand the mysteries of our universe.

American prosperity, I believe, is so much bigger than riches and spoils. American prosperity is the idea of creating the surplus we need so that we can then set our sights higher: on challenging the injustices of the present and enriching the future we may never ourselves benefit from, but others might. This unique notion of American prosperity - a prosperity that is for ourselves and others is what I think your Dada thought of when he contemplated a better life. A dream he ventured across the ocean and into an unknown land to be part of.

Because in America we are not just handed a brush and asked to paint something, we as a people, are driven to create the canvas on which others, namely our children, can paint. In America, we are called not just to be the consumers of prosperity, but to also be its producers.

Prosperity for ourselves and others.

I tell you all this because yesterday was an interesting day.

Yesterday, Vice President Joe Biden and Sen. Kamala Harris became the President and Vice President-elect of the United States, our country.

This is what your Dadi said to me in a text message last night:

Me: Did you watch Biden’s speech?

Dadi: Yes. Biden & Harris both speech was outstanding. I am happy. First time in my life I enjoyed president results.

Me: It’s crazy how much of a difference it feels because our VP is half Indian. It feels like we belong here now.

Dadi: Yes beta. You, Bo & Myles will touch the sky in this country. I see that. Papa’s dream will come true.

This week, 74 Million Americans asked someone who looks like you, and who looks like me, and who looks like mommy to serve the nation. 74 Million.

But why I tell you both this is not because I want to emphasize that some barrier has been broken and a glass ceiling has been shattered, though it has. I want to tell you what that ceiling shattering means.

It would be easy for us to feel today that this ceiling shattering is an opportunity for us individually to grow and thrive and become more prosperous, because an invisible barrier is now gone. That the broken ceiling is for us.

That is not the lesson of today.

The lesson of the day is that there is no more doubt that we belong here, and that does provide us more opportunity. But there are no more excuses to be made out of not belonging, either. We can no longer claim to feel that we don't belong and let it be a reason we don't contribute.

The lesson of today - with the shattered glass of broken ceilings - is that we have an invitation and obligation to live out the broad, ever expanding notion of American prosperity - a dream your Dada risked everything for - not just for ourselves, but for ourselves and others.

Whose shoulders am I standing on?

Thinking of who lifted me up, gives me courage and strength.

I stand on the shoulders of many.

My parents, my wife, my high-school teachers and club advisers, my professional mentors, civil servants that have worked in my community, scholars who have created knowledge I learned, my friends, my grandparents, veterans of war, veterans of peace, artists, kind strangers, and probably many more that I don’t know.

When asking myself, “whose shoulders am I standing on?” it compels me to keep pushing through adversity. Because, how could I insult all those who lifted me up by giving up now?

But it also raises another question in my mind, “who am I putting on my shoulders?”

Both questions are worth asking. Spending five minutes with those questions brought me to a place of peace, gratitude, and service.