Exponential Talent Development

What would have to be true for every person to contribute 100% of their potential to the world?

Most of us have a HUGE gap between the impact we actually make and what we are capable of.

Asking myself (and my teammates) this question helps me put it in perspective: How would you rate yourself on a scale from 1 to 100?

A 100 represents making the highest possible impact that your talent and potential allow.

A 1 represents completely wasting the opportunity to positively contribute to the world.

I think most of us, myself included, are much lower on this scale than we realize—maybe a 20 or 30 at best. This realization begs the question: Why is there such a discrepancy, and what can we do about it?

In my experience, there are three reasons we leave vast amounts of our talent and potential untouched. First, we may never be challenged enough to use it. Second, we're not in the right contexts to let our strengths shine. Third, we may not have the support we need to develop the untapped talent we possess.

If we were all fully auto-didactic, we’d have no problem. That's because an auto-didact can fully teach and develop themselves. But none of us are completely auto-didactic; we all need others' help to develop ourselves so that we make our fullest contributions.

Introducing Exponential Skills

The difficulty in fully developing ourselves and others is relevant in many contexts. In professional settings, we call this challenge "talent development." In family settings, it’s "parenting." In community spheres, it's "mentorship" in secular contexts and "faith formation" in spiritual ones. In all domains of our lives, fulfilling and contributing the totality of our potential to the world matters.

The question I like to ask to really push my thinking is: What would have to be true for everyone in the world to develop and contribute 100% of their potential? As I’ve reasoned through this, the only way we get to the point of the world contributing 100% of their talent is through an exponential feedback loop where the number of people helping others to grow and develop increases exponentially.

To make the jump to create a society with an exponential feedback loop for talent development, let me define some terms and introduce some concepts:

We are all contributors who bring our talent and potential to the world. Some of us contribute by making art, others by building bridges, creating knowledge, making cakes, or making decisions. In mathematical terms, think of this as a constant: c.

A coach is a contributor who also helps develop others. Coaches are a big deal because they help others close the gap between their potential and their contribution. Think of this as x(c), where x is the number of people a coach is able to develop.

A linear coach is a coach who also helps develop other people into coaches. Think of this as mx(c), where m is the number of other coaches the linear coach creates.

An exponential coach is a linear coach whose coaching tree goes on in perpetuity: the people I coach become coaches, and then those people create more coaches, and those people create more coaches, and so on. Think of this as (mx(c))^n, where n is the number of generations an exponential coach is able to influence the cycle of creating more coaches.

Visually, I think of it like this:

Barriers To Creating Exponential Coaches

To create exponential coaches, several significant challenges need addressing. These challenges revolve around how we internalize and transmit knowledge, and the intrinsic motivations behind our contributions.

Challenge 1: Recognition Gap — The further you get from a contributor, the less credit you get for your work. This recognition gap can demotivate those who do not see immediate returns on their efforts. Solution: To overcome this, we must cultivate inner motivation and focus on long-term impact rather than immediate recognition. Developing a sense of purpose that transcends acknowledgment allows leaders to dedicate themselves to creating a lineage of coaches, thus prioritizing legacy over accolades.

Challenge 2: Complex Idea Communication — For an idea to spread, the messenger must internalize it sufficiently to simplify and communicate it effectively. This requires a deep understanding of both the intellectual and emotional aspects of the idea. Solution: Coaches need to engage in profound introspection to grasp the nuances of their knowledge and experiences fully. This depth of understanding enables them to articulate these concepts clearly and simply, making them accessible and teachable.

Challenge 3: Teaching to Teach — Teaching others to teach is a complex task that involves not only passing on knowledge but also instilling the value and methodology of teaching itself. This requires a reflective understanding of one’s own teaching practices. Solution: Coaches should introspect on their teaching methods and motivations, understanding them deeply enough to convey their importance to others. This process ensures that the coaches they develop can, in turn, teach effectively, perpetuating a cycle of self-replication in coaching practices.

Mastering these challenges not only enhances our own potential but also multiplies our impact exponentially across our communities and industries.

Where Do We Even Start?

On a personal note, the person I call Nanna is not my grandmother by birth but rather by love; she's my father-in-law's mother. During a trip to England a few years ago, I asked her about the secret to a long and healthy life. Here are the highlights of what she said:

Make time for family, faith, and community.

Stay active; keep your body moving, whether it’s through dancing, walking a dog, or any other physical activity.

Find a way to express yourself—through music, art, writing, knitting, making movies, having a book club, or any other form—because expression is crucial to mental and emotional health.

That last imperative is so deeply intertwined with introspection. Isn’t expression just a word that means exploring our inner world and then sharing it outside of ourselves? We have to express to be sane and healthy.

I know this post is heady and meta. I’ve been thinking about this concept for months, and I’ve only just synthesized enough to share a muddy morsel of it. A fair question to ask is: Where, in the real world, do we even start?

For inspiration on where to start on our own journeys to become exponential coaches, we can take heed from Nanna. She was onto something.

To become an exponential coach, we have to introspect and express. And to introspect and express, we have to find a medium that works for us and allows us to explore our inner world. And once we find it, we have to just practice with that medium, over and over.

For me, that medium is writing. For others, it might be painting, photography, singing, or making pottery. For others still, it might be talking honestly with a good friend, praying, or starting a podcast.

The medium doesn’t really matter, as long as we just do it. As long as we take that time to introspect and express. That’s the first step we all can take to grow toward becoming exponential coaches. Expression is the first step to becoming an exponential coach.

Crafting a Resident-Centric CX Strategy for Michigan

What might a resident-centric strategy to attract and retain talent look like for Michigan?

Last week, I shared an idea about one idea to shape growth, talent development, and performance in Michigan through labor productivity improvements. This week, I’ve tried to illustrate how CX practices can be used to inform talent attraction and retention at the state level.

The post is below, and it’s a ChatGPT write-up of an exercise I went through to rapidly prototype what a CX approach might actually look like. In the spirit of transparency, there are two sessions I had with ChatGPT: this this one on talent retention. I can’t share the link for the one on talent attraction because I created an image and sharing links with images is apparently not supported (sorry). It is similar.

There are a few points I (a human) would emphasize that are important subtleties to remember.

Differentiating matters a ton. As the State of Michigan, I don’t think we can win on price (i.e., lower taxes) because there will always be a state willing to undercut us. We have to play to our strengths and be a differentiated place to live.

Focus matters a ton. No State can cater to everyone, and neither can we. We have to find the niches and do something unique to win with them. We can’t operate at the “we need to attract and retain millennials and entrepreneurs” level. Which millennials and which entrepreneurs? Again, we can’t cater to everyone - it’s too hard and too expensive. It’s just as important to define who we’re not targeting as who we are targeting.

Transparency matters a ton. As a State, the specific segments we are trying to target (and who we’re deliberately not trying to targets) need to be clear to all stakeholders. The vision and plan needs to be clear to all stakeholders (including the public) so we can move toward one common goal with velocity. By being transparent on the true set of narrow priorities, every organization can find ways to help the team win. Without transparency, every individual organization and institution will do what they think is right (and is best for them as individual organizations), which usually leads to scope creep and a lot of little pockets of progress without any coordination across domains. And when that happens, the needle never moves.

It seems like the State of Michigan is doing some of this. A lot of the themes from ChatGPT are ones I’ve heard before. Which is great. What I haven’t heard are the specific set of segments to focus on or what any of the data-driven work to create segments and personas was. If ChatGPT can come up with at least some relatively novel ideas in an afternoon, imagine what we could accomplish by doing a full-fidelity, disciplined, data-driven, CX strategy with the smartest minds around growth, talent, and performance in the State. That would be transformative.

I’d love to hear what you think. Without further ado, here’s what ChatGPT and I prototyped today around talent attraction and retention for the State of Michigan.

—

Introduction: Charting a New Course for Michigan

In an age where competition for talent and residents is fierce among states, Michigan stands at a crossroads. To thrive, it must reimagine its approach to attracting and retaining residents, and this is where Customer Experience (CX) Strategy, intertwined with insights from population geography, becomes vital. Traditionally a business concept, CX Strategy in the context of state governance is about understanding and catering to the diverse needs of potential and current residents. It's about seeing them not just as citizens, but as customers of the state, with unique preferences and aspirations.

Understanding CX Strategy in Population Geography

CX Strategy, at its essence, involves tailoring experiences to meet the specific needs and desires of your audience. For a state like Michigan, it means crafting policies, amenities, and environments that resonate with different demographic groups. Population geography provides a lens to understand these groups. It involves analyzing why people migrate: be it for job opportunities, better quality of life, or cultural attractions. This understanding is crucial. For instance, young professionals might be drawn to vibrant urban environments with tech job prospects, while retirees may prioritize peaceful communities with accessible healthcare. Michigan, with its rich automotive history, beautiful Great Lakes, and growing tech scene, has much to offer but needs a focused approach to highlight these strengths to different groups.

Applying CX Strategy: Identifying Target Segments

The first step in applying a CX Strategy is identifying who Michigan wants to attract and retain. This involves delving into demographic data, economic trends, and social patterns. Creating detailed personas based on this data helps in understanding various needs and preferences. For instance, a tech entrepreneur might value a supportive startup ecosystem, while a nature-loving telecommuter may prioritize scenic beauty and a peaceful environment for remote work. These insights lead to targeted strategies that are more likely to resonate with each group, ensuring efficient use of resources and increasing the effectiveness of Michigan's efforts in both attracting and retaining residents.

In the next section, we'll explore the importance of differentiation in attraction and retention strategies, and delve into the specific segments that Michigan should focus on. Stay tuned for a detailed look at how Michigan can leverage its unique attributes to create a compelling proposition for these key resident segments.

Importance of Differentiation in Attraction and Retention

Differentiation is crucial in the competitive landscape of state-level attraction and retention. It’s about highlighting what makes Michigan unique and aligning these strengths with the specific needs of targeted segments. For attraction, it might mean showcasing Michigan’s burgeoning tech industry to young professionals or its serene natural landscapes to nature enthusiasts. For retention, it involves ensuring that these segments find ongoing value in staying, like continuous career opportunities for tech professionals or maintaining pristine natural environments for outdoor lovers.

In focusing on segments like automotive innovators or medical researchers, Michigan can leverage its historic strengths and modern advancements. By tailoring experiences to these specific groups, the state can stand out against competitors, making it not just a place to move to but a place where people want to stay and thrive.

Overlap and Distinction in Attraction and Retention Strategies

The overlap and distinctions between attracting and retaining segments offer nuanced insights. Some segments, like tech and creative professionals, show significant overlap in both attracting to and retaining in urban settings like Detroit. This indicates that strategies effective in drawing these individuals to Michigan may also foster their long-term satisfaction. However, for segments with minimal overlap, such as medical researchers (attraction) and sustainable farmers (retention), strategies need to be distinct and targeted to their unique needs and lifestyle preferences.

Successful implementation teams will use these insights to create nuanced strategies for each segment. Avoiding a one-size-fits-all approach and recognizing the different motivations between someone considering moving to Michigan and someone deciding whether to stay is key. The primary pitfall to avoid is neglecting the distinct needs of each segment, which could lead to ineffective strategies that neither attract nor retain effectively.

Deep Dive into Experience Enhancements

Let’s delve into two specific segments: nature-loving telecommuters for attraction and tech and creative young professionals in Detroit for retention. For the nature-loving telecommuter, Michigan can offer unique experiences that blend the tranquility of its natural landscapes with the connectivity needed for effective remote work. Imagine "remote worker eco-villages" scattered across Michigan’s scenic locations, equipped with state-of-the-art connectivity and co-working spaces, set against the backdrop of Michigan's natural beauty. This not only caters to their desire for a serene work environment but also positions Michigan as a leader in innovative remote working solutions.

For tech and creative young professionals in Detroit, the strategy should be about fostering a dynamic urban ecosystem that offers continuous growth opportunities and a thriving cultural scene. Initiating a Detroit Tech and Arts Festival could serve as an annual event, bringing together tech innovators, artists, and entrepreneurs. This festival, coupled with collaborative workspaces and networking hubs, would not only retain existing talent but also attract new professionals looking for a vibrant, collaborative, and innovative urban environment.

Conclusion: Michigan’s Path Forward

Michigan is uniquely positioned to become a beacon for diverse talents and lifestyles. By adopting a resident-centric CX Strategy, informed by population geography, Michigan can tailor its offerings to attract and retain a dynamic population. It’s about moving beyond generic policies to creating experiences and opportunities that resonate with specific segments. The call to action is clear: Let's embrace innovation, leverage our unique strengths, and build a Michigan that’s not just a place on a map, but a destination of choice for a vibrant and diverse community. With these strategies, Michigan won’t just attract new residents – it will inspire them to stay, contribute, and flourish.

Attraction Segments Table:

Retention Segments Table:

How Might We Boost Labor Productivity in Michigan?

A cross-sector focus on labor productivity would increase prosperity for the State of Michigan.

What is Labor Productivity and Why Does it Matter?

I want you to care about labor productivity at the state level. Here’s a ChatGPT-supported primer on what labor productivity is and why it matters.

Labor productivity, the measure of output or value produced per unit of labor input, holds crucial significance at the state level. This economic metric directly impacts a state's health, competitiveness, and overall prosperity. States with higher labor productivity levels tend to experience robust economic growth, attracting businesses and creating job opportunities. This growth leads to tangible improvements in living standards, healthcare, infrastructure, and education, enhancing the quality of life for residents.

Conversely, low labor productivity can signal inefficiencies, hindering job creation and potentially leading to stagnant economies. In such cases, residents may face reduced access to quality healthcare and education, limited infrastructure development, and a less favorable living environment. Therefore, labor productivity serves as a vital tool for state-level policymakers, guiding their decisions on resource allocation, workforce development, and policies aimed at fostering economic growth. By prioritizing productivity, states can elevate the well-being of their citizens and build stronger, more prosperous communities.

Stanley Fischer, former Vice Chairman of the Federal Reserve Board of Governors, gave a talk in July 2017, titled "Government Policy and Labor Productivity." He expounded on the importance of labor productivity, stating that it is a basic determinant of the rate of growth of average income per capita over long periods. To understand the impact of productivity growth, consider this rule of thumb: divide 70 by the growth rate to estimate the doubling time of productivity. For instance, during the 25 years from 1948 to 1973, labor productivity grew at 3.25% annually, doubling in just 22 years. In contrast, from 1974 to 2016, the growth rate slowed to 1.75%, doubling the time to 41 years. This illustrates the significant difference in economic prospects across generations, highlighting the importance of productivity.

How has labor productivity been trending in the State of Michigan?

Overall, Michigan is not among the leading states with respect to it’s long run growth rate for labor productivity. Here’s an example that puts it into perspective.

Imagine two businesses, one in Michigan and the other in North Dakota, starting in 2007 with 100 units of output per unit of labor. Over the next 15 years, their paths diverge significantly. In Michigan, the average annual growth of 0.8% sees modest progress, reaching 113 units by 2022. In North Dakota, with a 2.7% growth, the productivity soars to 149 units of output per unit of labor. That difference is real money, real wealth, and real prosperity. This stark contrast in growth trajectories illustrates the transformative power of productivity rates.

For a more detailed analysis of recent trends (and data related to the thought experiment above), check out what the Bureau of Labor Statistics has published about state-level labor productivity, including the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic and specific changes in 2022. They’re fascinating.

The Opportunity

There is an opportunity to increase the long-run labor productivity growth rate in the State of Michigan.

Targeted strategies, rather than broad, sweeping changes, are more likely to yield positive results. The complexity of labor productivity issues necessitates a cross-sector vision and strategy, aligning efforts from the private sector, government, academia, the social sector, philanthropy, and the educational sector around a coordinated mission.

As I see it, taising labor productivity at the state level involves three distinct phases of work, with an assumption of continuous iteration.

The first phase is to deeply understand the problem. Michigan's world-class research universities should conduct research to understand what drives and hinders labor productivity in the state. This includes quantitative and qualitative research, examining factors like capital investment, skills development, and innovation, as well as under-utilized assets for improving productivity. We need to understand labor productivity deeply - by industry, by job type, by geography, and more.

The second phase involves a cross-functional group of major stakeholders and citizen groups selecting areas of focus (e.g., industry, types of jobs, regions of Michigan) that present unique opportunities for improving labor productivity. Success metrics and data infrastructure should be established early on to allow for dispassionate evaluation of implemented solutions. The cross-functional group could then moves to ideation, brainstorming solutions within each of the focus areas. Prioritization criteria - developed in advance - should then be used to narrow down possibilities, aiming to identify a set of small, quickly testable experiments.

This is worth nothing, the goal shouldn’t be to have huge transformation and an endless slate of big splash initiatives. At the beginning, learning is more important. And the best way to learn is to deploy small-scale programs quickly and cheaply.

After about a year, the group would start phase three by reconvening to assess the experiments, deciding what to scale, stop, or further test. This process will likely reveal systemic blockers, informing a data-driven policy agenda. The group can then iterate and scale the most effective strategies and pursue the most promising policy innovations for increasing labor productivity in Michigan.

I am excited about what’s happening in Michigan. A deep, cross-functional examination of labor productivity could bring together our most capable institutions and thinkers to collaborate and make our state more prosperous. We have great assets across sectors; all we need is the will and a framework to collaborate productively. Labor productivity matters and is a simple concept that can create an organizing framework and sense of shared purpose for driving transformational collaboration across sectors. We should strive to raise labor productivity together, at the state level.

In conclusion

Understanding and improving labor productivity is not just an economic concern; it's a pathway to enhancing the quality of life for everyone in Michigan. Let's not just witness the change – let's be the architects of it. There are so many exciting ideas (like the UM Detroit Innovation Center or the Growing Michigan Together Council) which might create opportunities for influencing labor productivity that are just starting in Michigan. Reach out, contribute your thoughts, and let's turn these ideas into actionable strategies. Together, we can forge a future where economic growth and prosperity are shared by all.

You can reach me at hello@neiltambe.com or leave a comment. I’m excited to hear from you.

Overcoming Ivy League rejection, finally

Overcoming the weight of Ivy League rejection, I discovered that the key to success and self-worth lies in embracing our own unique paths.

I was rejected by the Ivy League on three separate occasions. Twice while applying for undergraduate studies and once for grad school. The best I could manage was getting on the waitlist of one public policy school.

The Ivies were not my dream or my “league”, per se, but the league everyone, it seemed, wanted me to be in. Everyone around me implicitly signaled that Ivy League admission was the symbol of being elite and on a trajectory of success and respect. I don’t think I could've had an independent thought about the matter because the aura of the Ivy League was so insidious and pervasively woven into my psyche while I was growing up. Everyone else put their faith in the Ivy League, so I did too.

Ever since, it has been the source of whatever inferiority complex I have. I believe I am dumber than other people because I didn’t get into an Ivy League school. I thought I had to catch up, prove myself, and show everyone that I’m elite, too.

In a way, the Ivy League mythology is probably true. Extremely talented and capable people gain admission into Ivy League schools. And if I had too, I assume my career would’ve been easier and simpler. My “network” would have probably been more powerful and able to open stubborn doors. More people would’ve probably been knocking on my door, instead of the other way around.

And perhaps more importantly, I would’ve believed in myself more. It would’ve been a self-fulfilling cycle. If I had been admitted to the Ivy League, I would’ve believed that I was somebody. And because I believed that, I would’ve spent all that time I was insecure and engaging in negative self-talk actually being somebody. All the times I told myself stories about how I was too down-to-earth to go to the Ivy League, I could’ve been making a contribution.

The biggest trap of all this was not whether or not I got into an Ivy League school, but that I spent so much time in my life thinking about it, questioning what I was, and wondering what might’ve been. What a waste of time and energy.

What I realize now is that life and career are instances of product-market fit. Being able to make an impactful contribution is not just a matter of being talented but a matter of applying one's talents in the most impactful way. That is what I envy so much about Ivy Leaguers; nobody seems to tell them what they should do and what they should be. They seem like they have more mental freedom to just go in the direction they want, without too much questioning.

Even me, going to a relatively elite public university twice, people signal to me what I should be and what I should do all the time. They think they can fit me into the mold they want me to be. They think they can force me into their narrative. That’s what it feels like anyway.

Maybe none of this is true. Maybe nothing would’ve been different had I gotten into Harvard, Columbia, or any other Ivy League school. But putting this all on paper is proving to me that the mythology of the Ivy League has been in my head, rent-free, for a long time. I’ve been waiting for someone to validate my intellect, talent, and capability for so long.

—

The West Wing is probably my favorite television show of all time. I was turned onto it by Lee, who was one of my managers and role models when I was a consultant at Deloitte.

The funny part is that Lee was Canadian, and I figured if someone who wasn’t even born in the US was undeterred in his enthusiasm for a show dramatizing the American presidency, I would probably like it too.

One of my favorite moments of the show is the scene where the Chief of Staff, Leo McGarry, talks with the President and outlines a new strategy for the administration: “Let Bartlet be Bartlet.”

I think that's the lesson here: all of us need to find that moment when we find our footing. We should stop trying to be someone we're not. We need to accept that we should focus on being who we are, instead of obsessing over Ivy League admission, promotions, or awards.

I think we all need that moment when we realize we can embrace our individuality, whether it's "Let Tambe be Tambe," "Let Paul be Paul," "Let Detroit be Detroit," "Let Smith be Smith," or any other iteration that our identity requires.

This whole time, I've been depending on the Ivy League to give me permission to be myself. This whole time, I've been dangling my feet out, hoping for my choices to be validated by someone else.

The greatest lesson in all this has nothing to do with the Ivy League. The lesson here is that we need to create this moment where we grant ourselves permission to be ourselves.

In my case, the turning point came when a role model at work told me about his circuitous path and how he embraced it, reminding himself that sometimes "you've got to bet on yourself."

Maybe we can't will ourselves, completely on our own, to grant self-permission for self-authorship. It's okay and expected to need help, support, and encouragement. But I don't think we need an institution to "pick" us, either. I never needed the Ivy League to "Let Tambe be Tambe," though maybe that would've sped up the process. All I needed, and all that I think any of us need, is someone to remind us that the choice to grant ourselves permission is one that we're allowed to make.

The path is ours to walk if we're willing to claim it as our own.

Organizations are energy processes

Can you imagine what organizations would be like if there was so much human energy created that it was “too cheap to meter”? None of the world’s problems would be out of reach. Not one.

When I have an organizational problem - like an underperforming team, or an organization that seems like it’s stuck - I just want a mental model to help me figure it out that is practical and simple to use. As a practitioner, what I care about is having something that works.

I found inspiration after reading a Works in Progress article about making energy too cheap to meter: organizations are energy processes which create, harness, and apply human energy. To solve organizational problems, all we need to do is improve how the organization creates and applies energy.

Photo Credit: Unsplash @pavement_special

When I say “energy processes”, I mean something like what I’ve outlined below. Take nuclear fission as an example. The end to end process for creating and applying nuclear energy happens in four steps:

Accumulate a fuel source (uranium) from which energy can be created

Create energy from the fuel source (i.e., using a nuclear reactor)

Harness and transmit the energy (create electricity via a steam turbine and deliver it to a plug in someone’s home)

Apply it to something of value (the electricity goes into a lamp which someone uses to read a favorite book after sunset)

Organizations, similarly, are an energy process:

The fuel that powers organizations are people and the ideas, information, expertise, and the motivation they bring to the table (i.e., like the uranium)

Organizations try to get their people to put forth effort that can be used to create something of value (i.e., like the nuclear reactor).

Organizations then create systems to harness the efforts of their people and channel it into collective goals (i.e., like the steam turbine and power lines)

The organization tries to ensure all the energy they’ve created goes into something that the end customer actually cares about, which they can be compensated for (i.e., like the reading lamp used to read a novel)

Thinking of organizations as energy processes can help us understand organizational challenges quickly and simply. When I have an organizational problem I can quickly ask myself these four questions, and determine where my organization’s issues lie:

Do we have enough “fuel” to create energy?

How much energy are we creating?

How much energy are we harnessing?

Are we applying our energy to something of value?

You can be the judge of whether this mental model is simple and useful. The rest of this post gives some detail on how to actually use the energy process model to diagnose an organizational problem.

Question 1: Do we have enough “fuel” to create energy?

One of my favorite questions to ask a teammate is: what percent of your potential impact do you feel like you are actually making? In my experience, most people are not even close to fully applying their skills, talents and ideas. A tremendous amount of potential is wasted in organizations.

To get a sense of whether there’s sufficient “fuel” in your organization or the degree to which potential is wasted, look for the following:

Complaints - if people are complaining, it means they have energy they’re not using and care enough to say something.

Regrettable losses - if people are leaving your company and getting good jobs and promotional opportunities elsewhere, at least one other organization seems something that you do not

Ask the team - people care about whether they’re wasting their time and energy. If you ask them, they’ll tell you if they have talents and energy that are being wasted

Ask yourself this question: if I assumed the people around me had talent, potential, and cared, would I be acting differently? If you answer that question with a “yes” it probably means you have more potential around you than you realize.

In my experience, it is almost never the case that an organization lacks sufficient “fuel” to create energy. Don’t shift the blame to the people around you, look inward first.

Question 2: How much energy are we creating?

I loved The Last Dance, the ESPN Films miniseries the 1997-1998 NBA Champion Chicago Bulls. It was remarkable to me how that team seemed to try so hard, and how Michael Jordan was able to be a catalyst, pulling tremendous amounts of energy from his teammates. Watching the documentary, the energy being created was obvious.

To get a sense of whether your organization is creating energy, look for the following::

Body language and non-verbals - If you work in an office, walk the floor and observe people through the windows of conference rooms, so you can’t hear what people are saying - just observe with your eyes. Do people seem like they want to be there or are trying very hard? Do they look bored? It’s pretty easy to see the parts of your organization that have energy just by being a fly on the wall and paying attention.

Experiments - When people are trying new things - whether its practices, sharing new ideas, or under the radar projects that nobody has asked for - it’s a good indication that energy is being created. It doesn’t have to be a grand novelty. I just had a colleague the other day, our team’s agile scrum master, that tried out a new framework for debriefing our bi-weekly sprint of work. He literally changed our four usual questions to four new questions. He just did it. I immediately thought, “our team has some energy and psychological safety if our scrum master is trying new things - this is awesome.”

Spontaneous Fun - I love to see teams that celebrate birthdays, bring snacks to work, create trivia games, or play pranks on each other. These are examples of activities that take energy that don’t have to occur to get the job done, they’re just for fun. If people are spending time putting energy toward having fun at work, it probably means they have plenty of energy for the work itself

Engagement Scores - Again, there are lots of survey companies that can help your organization execute a simple engagement survey. The ball don’t lie, and you can track engagement over time. If you have high engagement it probably means your organization is creating a lot of energy..

Question 3: How much energy are we harnessing?

One of my favorite bits of comedy is the Abbott and Costello, “Who’s on first?” skit. Nobody has any idea what’s going on and they have a pointless conversation with no conclusion. It’s hilarious to watch, and an excellent illustration of what it feels like when there’s lots of energy around but it’s not being channeled and applied.

To get a sense of whether your organization is effectively harnessing and applying energy, look for the following:

Low value work - In a factory setting, it can be easy to spot waste. In corporate offices, it’s harder to spot or prove inefficiency. Low value work is a good tell. If people don’t have anything better to do than low-value, non-impactful, work it probably means your organization isn’t harnessing energy well because it’s going into something that’s not worthwhile. When people have the opportunity to do something more impactful, they tend to.

“It’s not my job” - The phrase “it’s not my job” or when people toss work over the fence, it’s a strong indicator that someone, somewhere, doesn’t know what their job actually is or that they have any direction on what to do. If your organization is constantly trying to offload work to someone else, it probably means energy is being wasted and that there’s ambiguity around what matters and what doesn’t.

Silos and Bad Meetings - Every organization I’ve ever worked for has talked about how they’re “siloed” or that there are a lot of “useless meetings”. These are signs, again, that teams don’t know what they’re doing or know what the organization’s goal is. If people have the time to tolerate “silos” and “bad meetings” (which are easily fixed with clear goals and basic discipline), it probably means the organization isn’t harnessing energy well.

Sprint and Milestone Velocity: There’s a great concept from Agile called “sprint velocity”. It basically measures how much work (measured in “points” which are pre-assigned) the team was able to accomplish in a given amount of time, usually two weeks. When the sprint velocity rises, it means the team accomplished more with the same amount of time and resources invested. You don’t need to operate on a sprint team to use the concept - just look at how long simple things things - like making decisions, building presentations, or executing a contract - takes to complete. If you find yourself saying, “there has to be a faster way to do this” it probably means your organization isn’t harnessing and applying it’s energy effectively.

In my experience, organizations harness just a fraction of the energy they create. Sometimes all it takes it setting a clear goal and making it clear “who’s on first”.

Question 4: Are we applying our energy to something of value?

This area of the framework is where the stereotypical strategy and marketing questions come into play, like “where do we play”, “how do we win”, and “how are we differentiated”. To get a broad sense of whether your organization is in a virtuous cycle of value creation or a doom loop of commotodization, here are some quick heuristics to get a sense how bad your strategy issues are:

Revenue per employee or market share growth - if your organization’s revenue per employee or market share (or it’s equivalent) lags comparable industry players, you’re probably not doing something right - either you have energy problems further upstream, or, your organization is putting your energy into something people don’t actually care about.

Races to the bottom - if your company is trying harder and harder to grow, but you are constantly feeling downward pressure on prices, it probably isn’t providing a compelling product that people are happy to pay a premium for - because they get more than they pay for. If you feel like you’re in a race to the bottom, you need your customers more than they need you.

Customer feedback and referrals - This is obvious, if people are telling their friends about you or sending you thank you letters, it probably means you’re doing something of value to them - they’re literally marketing you for free. That willingness to show gratitude and spread the word means you’ve done something worthwhile for them.

That Works in Progress article I linked was so interesting, to me. I’ve been thinking about it for weeks. It suggested that something that disproportionally drives human progress is when energy becomes exponentially cheaper. What the author argued for was trying to make it so that energy was so clean, so cheap, and so abundant that it would be “too cheap to meter”.

Most of the time, organizations I’ve been part of miss the big picture about their organizational problems. Thinking through the lens of the energy process model brings this to light: the biggest opportunities for organizational energy are in creating it, not harnessing it.

To be sure, improving how we harness and apply energy matters - there’s opportunity at each phase of the organizational energy framework. But creating energy is the largest and most game breaking area to explore, by far.

Can you imagine what organizations would be like if there was so much human energy created that it was “too cheap to meter”? None of the world’s problems would be out of reach. Not one.

Coaching Requires Dedicated, intensely Focused Time

The biggest error of coaching - not being intentional about it - can be avoided by dedicating real time to it.

People develop faster when they are coached well, but coaching doesn’t happen without intent. To be a better coach, start with making actual “coaching time” that is intentional and intensely focused.

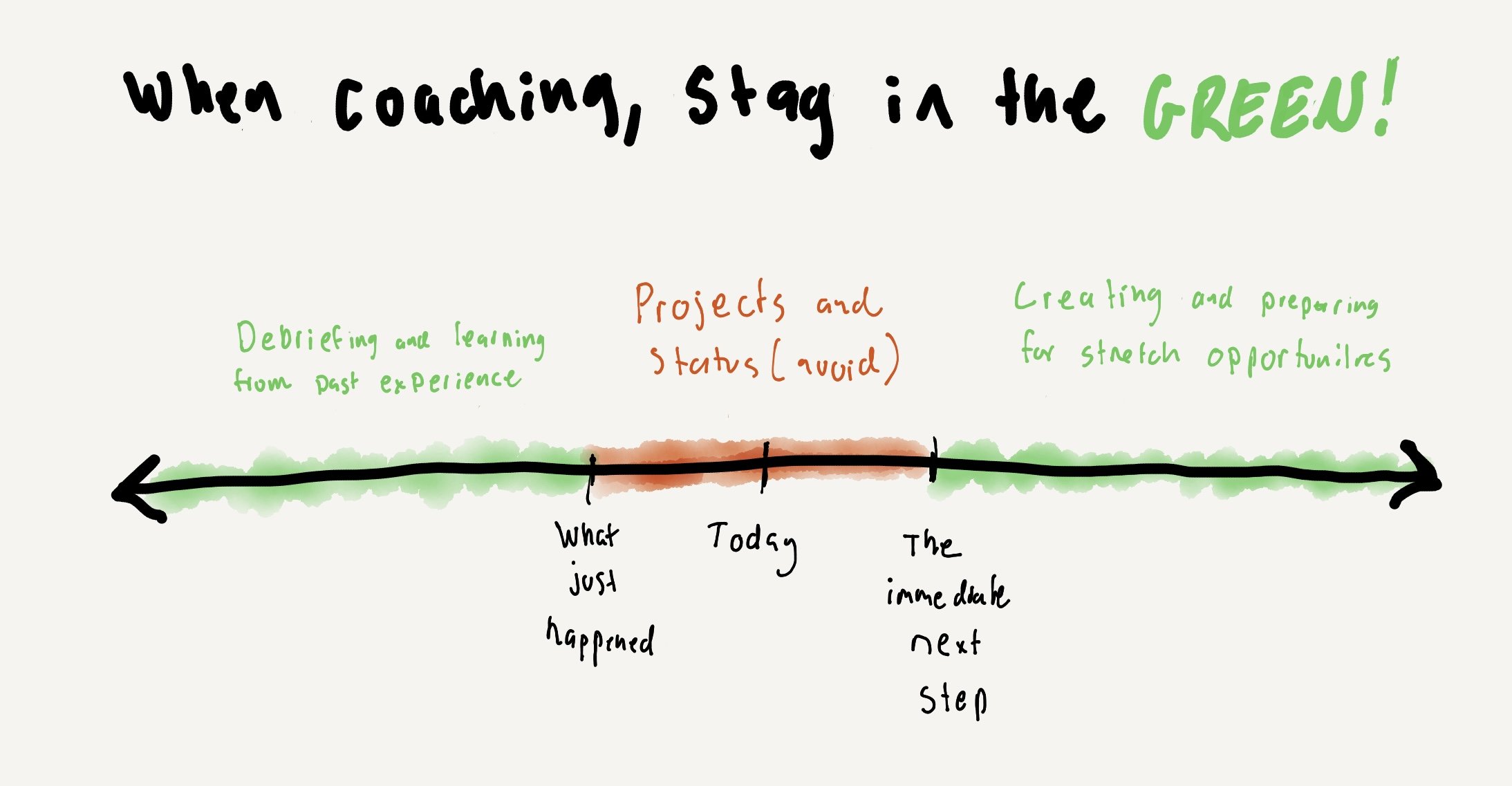

First, as a manager, we must dedicate one-to-one time with whomever we are trying to coach. 30 minutes per week, used well, is enough.

Second, that time can’t be about projects or status. It has to be spent on debriefing to glean learnings from past performance, or on how to create and prepare for future stretch opportunities.

Find a better way to manage status and project work than during a 1-1 and dedicate that time too and use it with intense focus. Personally, I like daily stand-ups from Agile/Scrum methodology and a once weekly full project review with the whole team.

Then, set a rule that during the dedicated time you will not talk about project status or the daily grind of work. If you dedicate time and hold firm to that rule, you’ll end up having a productive coaching conversation. Here are four questions that I’ve found work well to structure a 30-minute coaching conversation.

On a scale of 1 to 100, what percent of the impact you think you could be making are you actually making? (2-4 minutes)

Compared to last week, is your rate of growth accelerating, decelerating, or about the same? (2-4 minutes)

What do you want to talk about? (20-25 minutes)

What’s something I can do to help you feel respected and supported? (2-4 minutes)

This concept applies broadly: whether it’s coaching our team at work, our kids, our students, a volunteer group we’re part of, or co-coaching our marriage together with our partner, we must dedicate and focus the time. In my experience, the results of that dedicated time are exponential after just a few weeks.

To build a great team, get specific

To scale impact, every team leader has to build their team. Building a team is hard, but it’s not complicated.

To set us up for success, they key thing to do is get specific about the role, and the top 2-3 things we can’t compromise on in a candidate.

Building a team is hard, but it doesn’t have to be complicated.

What I’ve learned when trying to build teams (whether serving on hiring committees, recruiting fraternity pledges, or volunteer board members) is that most of the time we’re not specific enough.

To build a great team, we can’t just fill the role with a body. We can’t count on the perfect candidate either - there are no unicorns. Instead, we should be clear about the role, and the attributes that we can and cannot compromise on.

Here’s a video with a tool / mental model on how to actually do that.

Bad Managers May Finally Get Exposed

If we’re lucky, the Great Resignation may only be the beginning.

Hot take: the shift to remote work will finally expose bad managers, and help good managers to thrive.

If I were running an enterprise right now, I’d be doubling down HARD on improving management systems and the capabilities of my organization’s leaders. Why?

Because bad management is about to get exposed.

This is merely a prediction, but even with all the buzz about the “Great Resignation” I actually think most organizations - even ones that are actively investing in “talent” - are underrating the impact of workforce trends that have started during the pandemic. The first order effect of these trends manifests in the Great Resignation (attrition, remote work, work-life balance) but I think the second-order effects will reverberate much more strongly in the long-run.

Here’s my case for why.

A fundamental assumption a company could make about most workers, prior to the pandemic, was that they were mostly locked in to living and working in the same metro or region as their office location. Now, hybrid and fully remote work is catching on, and this fundamental assumption of living and working in the same region is less true than it was three years ago.

This shift accelerates feedback loops around managers in two ways. One, it lowers the switching costs and broadens the job market for the most talented workers. Two, it opens up the labor pool for the most talented managers - who can run distributed teams and have the reputation to attract good people.

I think this creates a double flywheel, which creates second order effects on the quality of management. If this model holds true in real life, good managers will thrive and create spillover effects which raise the quality of management and performance in other parts of their firms. Bad managers, on the contrary, will fall into a doom loop and go the way of the dinosaur. Taken together, I hope this would raise the overall quality of managers across all firms.

Here’s a simple model of the idea:

Of course, these flywheels most directly affect the highest performing workers in fields which are easily digitized. But these shifts could also affect workers across the entire economy. For example, imagine a worker in rural America or a lesser known country, whose earnings are far below their actual capability. Let’s say that person is thoughtful and hard working, but is bounded by the constraints of their local labor market.

Unlike before, where they would have to move or get into a well known college for upward mobility - which are both risky and expensive - they can now more easily get some sort of technical certification online and then find a remote job anywhere in the world. That was always the case before, but the difference now is that their pool of available opportunities is expanded because more firms are hiring workers into remote roles - there’s a pull that didn’t exist before.

Here’s what I think this all means. If this prediction holds true, I think these folks would be the “winners”:

High-talent workers (obviously): because they can seek higher wages and greater opportunities with less friction.

High-talent managers: because they are better positioned to build and grow a team; high-talent workers will stick with good managers and avoid bad ones.

Nimble, well-run, companies: companies that are agile, flexible, dynamic, flat, (insert any related buzzword here) will be able to shape teams and roles to the personnel they have rather than suffocating potential by forcing talented people into pre-defined roles that don’t really fit them. A company that can adjust to fully utilize exceptional hires will beat out their competitors

Large, global, companies: because they have networks in more places, and are perhaps more able to find / attract workers in disparate places.

Talent identification and development platforms: if they’re really good platforms, they can become huge assets for companies who can’t filter the bad managers and workers from the good. Examples could be really good headhunters or programs like Akimbo and OnDeck.

All workers: if there are fewer bad managers, fewer of us have to deal with them!

And these are the folks I would expect to be the “losers”:

Bad managers: because they’re not only losing the best workers, they’re now subject to the competitive pressure of better managers who will steal their promotions.

Companies with expensive campuses: because they’re less able to woo workers based on facilities and are saddled with a sunk cost. Companies feeling like they have to justify past spend will adjust more slowly - ego gets in the way of good decisions, after all.

Most traditional business schools: because teaching people to manage teams in real life will actually matter, and most business schools don’t actually teach students to manage teams in real life. The blueboods will be able to resist transformational change for longer because their brands and alumni connections will help them attract students for awhile. But brands don’t protect lazy incumbents forever.

This shift feels like what Amazon did to retailers, except in the labor market. When switching costs became lower and shelf space became unlimited, retailers couldn’t get by just because they owned distribution channels and supply chains. Those retailers resting on their laurels got exposed, because consumers - especially those who had access to the internet and smartphones - gained more power.

And two things happened when consumers gained more power: some retailers (even large ones) vanished or became much weaker, and, the ones that survived developed even better customer experiences that every consumer could benefit from. It’s not a perfect analogy because the retail market is not exactly the same as the labor market, but switch “consumers” out with “high-talent workers” and the metaphor is illustrative.

Of course, a lot of things must also be true for this prediction to hold, such as:

We don’t enter an extended recession, which effectively ends this red hot labor market

Some sort of regulation doesn’t add friction to remote workers

Companies and workers are actually able to identify and promote good managers

Enough companies are actually able to figure how to manage a distributed workforce, and don’t put a wholesale stop to remote work

I definitely acknowledge this is a prediction that’s far from a lock. But I honestly see some of these dynamics already starting. For example…

The people that I see switching jobs and getting promoted are by and large the more talented people I know. And, I’m seeing more and more job postings explicitly say the roles can be remote. And, I see more and more people repping their friends’ job postings, which is an emerging signal for manager quality; I certainly take it seriously when someone I know vouches for the quality of someone else’s team.

So, I don’t know about y’all, but I’m taking my development as a manager and my reputation as a manager more seriously than I ever have. If you see me ask for you to write a review about me on LinkedIn or see me write a review about you, you’ll know why! I definitely don’t want to be on the wrong side of this trend, should it happen - you probably don’t.

Bad managers, beware.

High Standards Matter

Organizations fail when they don’t adhere to high standards. Creating that kind of culture that starts with us as individuals.

I’ve been part of many types of organizations in my life and I’ve seen a common thread throughout: high standards matter.

Organizations of people, - whether we’re talking about families, companies, police departments, churches, cities, fraternities, neighborhoods, or sports teams - devolve into chaos or irrelevance when they don’t hold themselves to a high standard of conduct. This is true in every organization I’ve ever seen.

If an organization’s equilibrium state is one of high standards (both in terms of the integrity of how people act and achieving measurable results that matter to customers) it grows and thrives. If its equilibrium is low standards (or no standards) it fails.

If you had to estimate, what percent of people hold themselves to a high standard of integrity and results? Absent any empirical data, I’ll guess less than 25%. Assuming my estimate is roughly accurate, this is why leaders matter in organizations. If individuals don’t hold themselves to high standards, someone else has to - or as I said before, the organization fails.

Standard setting happens on three levels: self, team, and community.

The first level is holding myself to a high standard. This is basically a pre-requisite to anything else because if I don’t hold myself to a high standard, I have no credibility to hold others to a high standard.

The second level is holding my team to a high standard. Team could mean my team at work, my family, my fraternity brothers, my company, my friends, etc. The key is, they’re people I have strong, direct ties to and we have an affiliation that is recognized by others.

To be sure, level one and level two are both incredibly difficult. Holding myself to any standard, let alone a high standard, takes a lot of intention, hard work, and humility. And then, assuming I’ve done that, holding others to a high standard is even more difficult because it’s really uncomfortable. Other people might push back on me. They might call me names. And, it’s a ton of work to motivate and convince people to operate at a high standard of integrity and results, if they aren’t already motivated to do so. Again, this is why (good) leadership matters.

The third level, holding the broader community to a high standard, is even harder. Because now, I have to push even further and hold people that I may not have any right to make demands of to a high standard. (And yes, MBA-type people who are reading this, when I say hold “the broader community” to a high standard, it could just as easily mean hold our customers to a high standard.)

It takes so much courage, trust, effort, and skill to convince an entire community, in all it’s diversity and complexity, to hold a high standard. It’s tremendously difficult to operate at this level because you have to influence lots of people who don’t already agree with you, and might even loathe you, to make sacrifices.

And I’d guess that an unbelievably small percentage of people can even attempt level three. Because you have to have a tremendous amount of credibility to even try holding a community to a high standard, even if the community you’re operating in is relatively small. Like, even trying to get everyone on my block to rake their leaves in the fall or not leave their trash bins out all week would be hard. Can you imagine trying to influence a community that’s even moderately larger?

But operating at level three is so important. Because this is the leadership that moves our society and culture forward. This is the type of leadership that brings the franchise to women and racial minorities. This is the type of leadership that ends genocide. This is the type of leadership that turns violent neighborhoods into thriving, peaceful places to live. This is the type of leadership that ends carbon emissions. This is the type of leadership, broadly speaking, that changes people’s lives in fundamental ways.

I share this mental model of standards-based leadership because there are lots of domains in America where we need to get to level three and hold our broader community to a high standard. I alluded to decarbonization above, but it’s so much more than that. We need to hold our broader community to a high standards in issue areas like: political polarization, homelessness, government spending and taxation, gun violence, health and fitness, and diversity/inclusion just to name a few.

And that means we have to dig deep. And before I say “we”, let me own what I need to do first before applying it more broadly. I have to hold myself to a high standard of integrity and results. And then when I do that, I have to hold my team, whatever that “team” is, to a high standard of integrity and results. And then, maybe just maybe, if the world needs me to step up and hold a community to a high standard of integrity and results, I’ll even have the credibility to try.

High standards matter. And we need as many people as possible to hold themselves and then others to a high standard, so that when the situation demands there are enough people with the credibility to even try moving our culture forward. And that starts with holding ourselves, myself included, to a high standard of integrity and results. Only then can we influence others.

Equality begins at home

Women pay a tax on their talent. It’s not fair.

Women are not treated fairly in America.

The splitting of daily domestic responsibilities is one way that this unfairness manifests (there are many more), and it’s the one area I kinda sorta understand so I’ll stick to this narrow subject.

In the past year, two unexpected things happened to help me learn this unfairness existed, even in our own home. First, I was furloughed from my job. My wife became our primary breadwinner and I picked up the role of lead parent, plus 20 hours a week of contract work. Second, Robyn became my office mate and I began seeing up close the tax domestic responsibilities put on her.

I never actually understood “mom brain” until I was trying to do what Robyn had been doing since Bo was born: juggling like 5,000 different details and bids for her time. It’s more than a full time job. But beyond that, it shreds your brain and zaps energy.

I lost a measurable amount of weight within week of becoming lead parent. It was hard to be at my best, because I was mentally and physically blitzed, every day.

And, I felt less valuable, honestly, despite Robyn’s best efforts to make me feel honorable and appreciated. Our culture doesn’t make domestic work heroic, even though it is.

Women bear a disproportionate amount of these domestic responsibilities in America. This is a fact. I liked to think I was some sort of exception and this was not true for us, that somehow our distribution was fair despite the odds.

Wrong. I was lying to myself. Our split of home duties wasn’t egregiously unfair, but they weren’t fair. Which we are working on and have been for the past year. It was tough to read as a man, but if you’re interested in this idea, check out the book Fair Play for a ton of stories and a framework for working toward a fair arrangement.

Of course, what “fair” looks like varies by family. A family with historic gender roles can be as fair or unfair as a family with both partners working outside the home. Both can be great setups, but both can also be unfair - usually for women.

This unfairness makes women pay a tax on sharing their talents with the world. It’s just much harder to contribute something - whether at work, through community volunteering, or through a hobby or passion - when you have a case mom brain induced by an unfair balance of domestic responsibilities.

Robyn, still, gets interrupted more when I’m on duty with the kids because she’s the one they want to kiss their boo-boos. Robyn, still, gets her day hijacked more by “emergencies.” Robyn, still, gets more judgement if we have a messy house, messy kids, or miss some sort of caregiving responsibility.

And so she’s taxed on being able to contribute her talents fully. And because she’s my officemate now, I see firsthand how she has to work harder at everything to make the same contribution I can. Which isn’t fair.

The worst part is what the world is missing out on, by treating women unfairly. Whether it’s through a job, a hobby, or community effort, our culture taxes the gifts and talents of women. The loss of that taxation of talent is probably measured in the billions and trillions of hours, dollars, or quality of life years.

So what do we do differently? And by we I mean my brothers, because I’m writing to other men - husbands and fathers, specifically - today. I think we have to do the work with our partners to determine what’s fair in our own families. Because I’m convinced equality has to begin at home.

And it’s for real really uncomfortable to talk about, because even though we may think we have a fair situation going (I did), we probably don’t (we didn’t). And I felt a lot of guilt realizing Robyn was paying a tax on her talents, directly because of me. I was unintentionally harming her. And owning up to that sucks, but don’t we owe that to our partners and the other important women in our lives?

But gender equality is really good for us, too. We have more social permission to be part of home life. Like being fathers or caregivers. We can say, “yup, I can work on this, but after dinner and bedtime”, or, “no, I can’t make the call because my wife has a commitment and I’m watching my kids” with less stigma.

I think if we do the work at home, more equal public policy like paid family leave, childcare support, or reforms to prevent harassment and domestic violence probably follow in spades. Because we’ll have walked that road with our partners and will be emphatically motivated to advocate their interests, because now we understand more of the tax they pay.

This year has opened my mind to the win-win generated by gender fairness and equality, however that’s defined for our individual families. The sacrifice is us doing the difficult work to make things fair at home. But that sacrifice will be so worth it if we choose to make it.

Who is low-potential, exactly?

We have exclusive programs for people with “high-potential”. If we do that, then who exactly is “low-potential”?

There are lots of organizations that have programs for “high-potentials”, cohorts of “emerging leaders”, or who’s who lists for “rising stars”.

But lately, I’ve wondered: if we have programs for “high-potential” talent, who is “low-potential”, exactly? It’s audacious to me that we consider anyone low-potential.

With the right role, coach, opportunities, and expectations, my experience suggests that just about anyone can grow and thrive and make a tremendous contribution to whatever organization they are part of. Moreover, in my experience the most important ingredient needed for someone to be “high-potential” is that they want and are motivated to grow and be better.

It seems to me that a better approach than creating high-potential programs or leadership development cohorts that are exclusive is to design them in such a way that anyone who wants to opt-in and put in the work can participate.

And wouldn’t that be better anyway? Aren’t our customers, colleagues, shareholders, and culture all better off if everyone who wanted to had a structure where they could grow to their fullest potential? Even if not everyone ends up being a positional leader, don’t we want every single person in our companies to be better at the behavior of leading?

I don’t buy the excuse that it would take too many resources to design structures for developing potential that’s inclusive rather than exclusive. Software makes interaction much cheaper and scalable. People are really good at developing themselves and learning from their peers, given the right environment. And, in my experience most people are willing to coach and mentor someone coming up if that person is eager to learn and grow.

I definitely would want to be persuaded in a different direction,.however. Because to me, employing the best ways to prevent human talent from being wasted is worth doing, even if it’s not my idea that wins.

But again, if someone is truly motivated to grow and make a greater contribution, who of those folks are low-potential, exactly?

Clear, shared, expectations: in projects and parenting

My wife made a brilliant parenting move this week.

Our older son is 3, and we’re trying to work on table manners with him. At least 5 days a week we have been getting into some sort of tussle with him over playing with his food, chewing with his mouth open, or deliberately making a mess. Mealtime has been the most common trigger of friction between us all.

And the other day I asked Robyn what she wanted to do, and she calmly replied, “I have a plan.”

What she did was simple and immediately effective. When we were serving the next meal, she set expectations for our son as she was putting down his plate. “The expectation is that we eat Cheerios with a spoon, blueberries you can eat with your hands.” And on she went about sitting down properly and what can be dipped and what cannot.

Her plan of setting clear expectations, in advance, worked immediately. It was a master stroke.

—

My work colleagues and I have been experimenting with approaches to clarify expectations, too. Instead of doing a weekly check-in with a traditional project board, we made a “why-what-how” board.

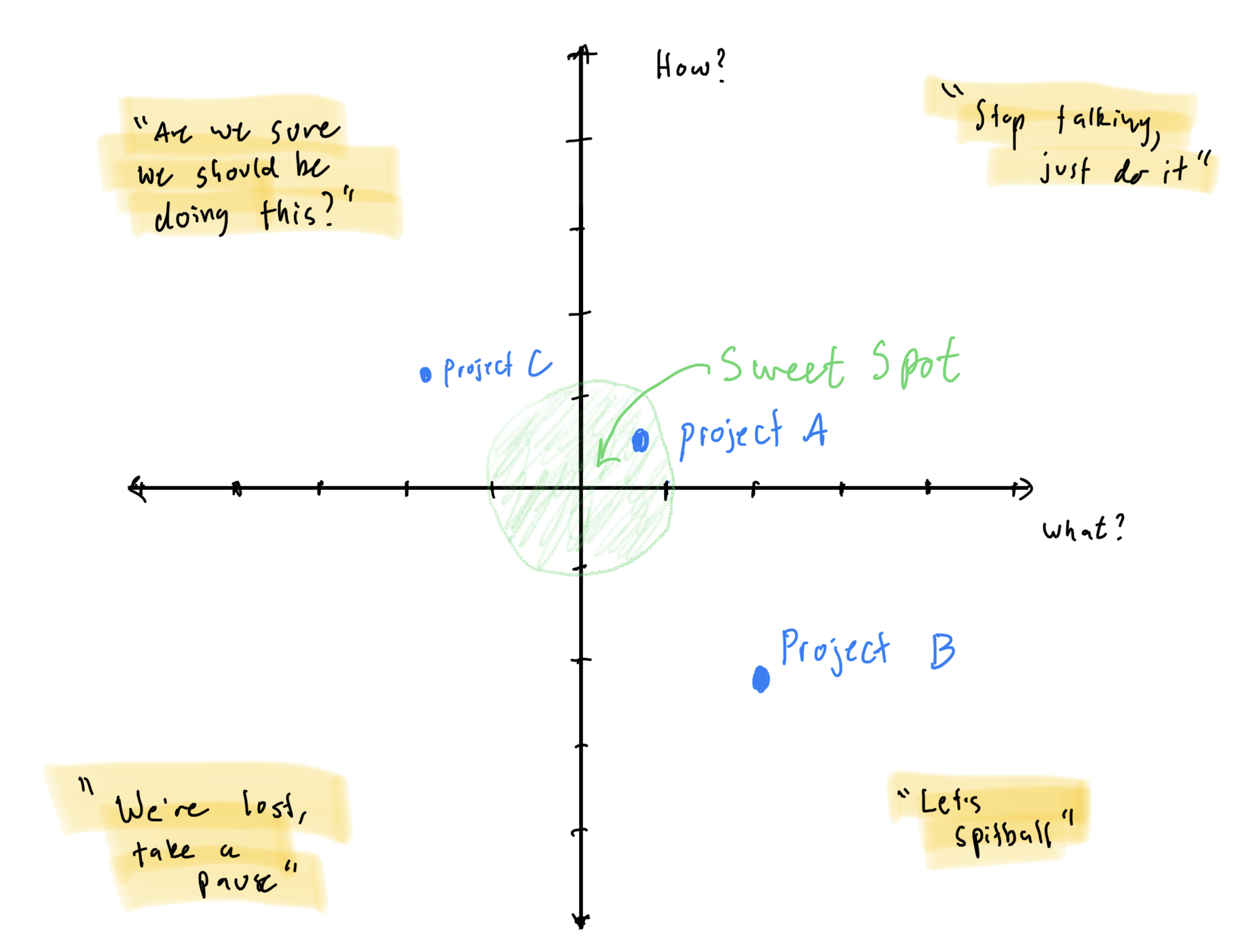

Here’s a representation of what our board (which is just a slide in PowerPoint) looks like:

What we do each week is re-score and re-plot our projects on this chart together. The goal of this exercise is to ensure the project is in the sweet spot of clear, shared, expectations.

The x-axis is the what. We make sure we understand what the intended outcome of the project is. Do we understand the deliverables? Do we understand what success looks like and what result we are trying to create? If the value is left of the origin it means the what isn’t clear enough. If the value is to the right of the origin, it means we are over analyzing the intended outcome and/or talking about it more than we need to.

The y-axis is the how. We make sure we understand the steps we need to take to achieve the intended outcome of the project. Do we understand the major milestones and next steps? Do we have a plan for how we’ll actually get the deliverables and analyses done? Do we understand the roadblocks ahead? If the value is below the origin, it means the how isn’t clear enough. If the value is above the origin, it means we’re micromanaging the project or getting too prescriptive about how it should be done.

We ask ourselves each week, usually during our Monday morning check-in, where are we at for each project. If we’re outside of the sweet spot, we spend some time clarifying the what, the how, or both.

Each quadrant, conveniently, has a nicely fitting heuristic which gives us a nudge on how to get back to the sweet spot:

High how, high what: we are talking too much. Let’s just take action.

Low how, high what: we understand what we’re trying to accomplish, but need to talk about how we get there. Let’s spitball and figure it out.

Low how, low what: we’re totally lost. We need to take a pause, reset and understand everything clearly where we are. This is the quadrant where the project is at risk and we have to dig out immediately.

High how, low what: this is the we might be wasting our time quadrant. If we don’t know what we’re trying to accomplish, even if we nail the project tactically, are we even solving the correct problem? We need to clarify the what (usually by escalating to the sponsor) or end the project.

What’s not plotted on the graph, but in the data table that powers the graph, are a few other elements: the why and who and the immediate next step.

The why and who has been a recent addition to our board, that we added a few weeks after trying this out for the first time. This value is the motivation for the project. Why does it matter, who is it for, what positive impact is this project in service of, why should anyone care about it? We think about our who as one of four general parties, that are applicable, honestly, to any organization. Any project has to ultimately impact at least one of these stakeholders in a big way to have a compelling why:

Our customer

Our owners or shareholders

Our colleagues

Our society or the communities in which we operate

If we can’t think of a compelling reason why what we’re doing matters to at least one of these four stakeholders, why are we even working on this project? We push ourselves to understand why, for our own motivation and to ensure we’re not doing something that doesn’t actually matter.

We also ensure everyone knows what the immediate next step is. If that’s not clear we establish it right there so there’s no reason we can’t take action right after our meeting.

Our team only started experimenting with this since the beginning of the year, but I’ve been finding it to be much more helpful than a traditional project board where the conversation revolves around the ambiguous concept of “status” and “accountability”.

Instead of checking our “status” non-specifically, and being reactive to a project that is “off-track”, we ensure that everyone on the team has clear, shared, expectations on each project, and we chip away at getting into the sweet spot of clarity on a weekly basis. By using this approach, we end up teasing out problems before they become large. Because after all, how often do projects get off-track if the why, what, and how of the project are clear to everyone, all the time? Rarely.

This approach is also much less autocratic than a traditional project board. Instead of the “manager” being dictatorial and projecting authority, this process feels much more democratic and equal, relatively at least. We all are working through the why, what, and the how together and even though one of us on the team is the titular “manager”, it feels more like we’re all on equal footing.

This is a good thing because everyone is more able to speak up, ask questions freely, and bring their talents forward to benefit the team and the people we’re serving. It’s less of an exercise where everyone is afraid of not having hit their milestones and therefore trying to tap dance around the status of the project.

There is of course a time and place for “status” and “accountability”. Of course, deadlines and results matter and we have to hit those. But what I’ve found so far is that by having clear, shared, expectations we are in a perpetual state of forward motion. We hit our deadlines as a natural consequence of having clarity. As is often said, but no less true, an ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure.

As is usually the case, what my wife and I are learning as parents is incredibly relevant to what we are learning about management and leadership. In this case the lesson is simple: clear, shared, expectations lead to better results (and less strife).

The Weekly Coaching Conversation

Coaching others is definitely the most important and rewarding part of my job. When I took on this responsibility, I worried: would I waste my colleagues’ talent? How do I help them grow consistently and quickly?

Here’s a summary of what I‘ve been experimenting with.

Experiment 1: Dedicate 30 minutes to coaching every week

I raided my father-in-law’s collection of old business books and grabbed one called The Weekly Coaching Conversation: A Business Fable About Taking Your Game and Your Team to the Next Level.

The idea in it is simple: schedule a dedicated block of 30 minutes every week with each person you’re responsible for coaching. I thought it was worth trying. As it turns out, it was. Providing support, feedback, and advice falls by the wayside if it’s not part of the weekly calendar - at least for me.

Experiment 2: Ask Direct Questions

We start each 30 minute weekly meeting the same way, with a version of these two questions:

On a scale of 1-100 how much of your talent did we utilize vs. waste this week?

This question is useful because it’s direct feedback from the person I’m trying to coach. I can get a sense of what they need. Most of the time, what is holding them back is either me, or something I can support them with, such as: more clarity on the mission, an introduction to a subject-matter expert, some time to spitball ideas, or just some space to explore. This is also a helpful question to ask, because when the person I’m coaching is excited and thriving, I get to ask them why, and do more of it.

What’s one way you’re better than the person you were last week?

This question is useful because it helps make on-the-job learning more explicit and concrete. We get to unpack results and really see tangible progress. Additionally, I get a sense of what the person I’m coaching cares about getting better at which allows me to tailor how I coach them.

Experiment 3: Stop controlling the agenda

At the beginning, I would suggest an agenda for our weekly coaching sessions. But over the course of 3-5 weeks, I transitioned responsibility for setting the agenda to the person I’m coaching. This works out better because we end up focusing our time on what matters to them, rather than what I think matters to them (which is good, because I’m usually wrong about what matters to them).

It also works out well because my colleagues are in the driver’s seat for their own development. And that fosters intrinsic motivation for them, which is really important for fueling real growth. I certainly raise issues if I see them, but it frees up my headspace and my time to be responsive to what they ask of me.

I still have a lot of improvement to do here, but I spend a lot less time talking and much more time asking questions and being a sounding board by letting go of control of the agenda. Which seems to work out better for my colleagues’ growth.

What I’m thinking about now (I haven’t figured it out) how do I know that my support is actually working, and leading to real growth and development?

—

I am absolutely determined to discover ways to stop wasting talent, in my immediate surroundings and across the organizational world. It’s a moral issue for me. And I figure a world with less wasted talent starts with me wasting less talent.

I’ll continue to share reflections on what I’m experimenting with so all of us that care about unlocking the potential of people and teams have an excuse to find and talk to each other.