We Are All Near Misses

That we all have moments of near-death, is a reason to have a little extra grace.

When I hold our newborn son, Griffin, I tell him, “I’m glad you’re here.”

I don’t know what else to say—it just comes out. Like a reflex, like an exhale, just from being close to him. And every time I say it, I start to cry. Sometimes the tears make it all the way to my eyes, but sometimes they just wiggle in my throat, staying caught there for a moment.

It’s such a beautiful and difficult thing to say.

It’s beautiful because it means something like, “Your mere presence with me is enough to bring me joy. You don’t need to be anything or do anything—you are here, and that alone brings me comfort and happiness. I love you exactly as you are.”

But it’s also difficult. Difficult because it reveals something raw in us. Because it also means, “I was, and can often feel, lonely. I was whole before you, but I was missing something. And now that you’re here, I am better than I was.”

The beauty and the difficulty of “I’m glad you’re here” both come from a place of longing.

It chokes me up every time. When I say it to my kids, or my wife. Even to our dog, or to my plants as I sing and talk to them while in our vegetable garden.

If I say it, I mean it. And when I mean it, it hits something deep and tender.

I understand why this phrase opens, but also rattles, my soul better now. Because when I say “I’m glad you’re here” to Griffin, I know in the sinews of my muscle that he may not have been.

We were lucky. When he was born accidentally at home because of Robyn’s disorientingly fast labor, there were no complications. No umbilical cord tied around his neck. No fluid in his lungs needing to be pumped out.

Had anything gone wrong, I would’ve been trying to save his life with a spatula and a pair of kitchen shears until the ambulance arrived. I thank God regularly that I didn’t have to try.

Griffin, truly, was a near miss. God rushed the process, but He cut us a break. Griffin is here. And every day, when I tell him, “I’m glad you’re here,” I feel the weight of that truth—he very easily might not have been.

And I feel it, too, when I look at my wife, Robyn. When I remember that she, too, had a near miss. She could have bled out delivering Griffin, right there on our family room floor. Instead, she was holding him in front of the fireplace, both of us the beneficiaries of a not-so-small mercy.

Near misses.

And as I traced this thought further, I realized—we are all near misses.

Some are dramatic, life-or-death moments. Others, like mine, are quieter, only revealing themselves in hindsight.

The week before COVID really broke open, I would’ve attended a community event with my old colleagues at the Detroit Police Department, but I had to travel out of town for a wedding. Turns out, it was a super spreader event, before we even had that term in our lexicon. I may not have died, but who knows what it would’ve been like to contract COVID before we knew how serious it was, with a three-month-old baby at home. Near miss.

A friend of mine was born two months early, in a town with only basic medical facilities. Even her family elders doubted she’d survive. But she’s here. Another near miss.

Almost all of us have been close to these moments, whether it was the car that almost swiped us on the freeway, the stairs we almost fell down, or the hard candy we almost choked on. And those are just the near misses we know about.

And that’s when it hit me: every single person I encounter—every stranger, every friend, every difficult person—was a near miss, too.

At some point, they almost weren’t here.

There was a homily at Mass once that sticks with me. I don’t remember what the Gospel reading was that day, but the point stuck—try to see someone as God sees them.

And maybe one way to do that is to remember: no matter who they are, no matter how annoying or rude the person in front of me is, there was some moment in time when they almost didn’t make it.

It’s easy to offer grace to someone who just survived a life-threatening event. We instinctively soften, give them space, recognize the weight of what they just went through.

But what I realized today—when I was trying to understand why a four-word sentence brings me to tears—is that everyone has brushed past death at some point.

Everyone has almost not been here.

Which means I can have a little more grace than I do sometimes.

So today, I’m trying, even for the random guy at the grocery store who tried to punk me by swiping a box of tea out of my cart while his friend very inconspicuously filmed it.

Because even though I may need a nudge to remember it sometimes—

I’m glad they’re here.

And maybe, just maybe, they’re glad I’m here, too.

This Year, I Finally Stopped Arguing with a Ghost

We don’t have to keep justifying our choices to the ghosts of our past selves.

2025 is our year of joy.

We’re welcoming our final child into the world, and we want to remember it—really soak it in since it’s the last time, ya know?

One of my three New Year’s resolutions is something I’d never have imagined—even two years ago: no career planning. Exactly as it sounds, I do not want to spend a single shred of time or energy obsessing over my next professional step.

I’ll never remember the sound of our baby’s laughter or the way they hold my finger if I’m simmering in the back of my mind about my next move or some other bullshit like that.

This resolution is shocking for me because I’ve quietly obsessed over my career for almost three decades. I don’t know what it’s like not to think about achievement. From my earliest school days, my worth was tied to what I achieved—anything that could help me get into an elite college and land a lucrative, respected job at the top of whatever ladder would crown me "the best of the best."

For those of you who didn’t grow up as South Asian immigrant kids, this might sound preposterous—even funny. But for those of us who did, this is no joke. The pressure to perform, to win approval through achievement, feels like it’s coded into our DNA—maybe even hidden in the spices of our ancestral cuisine.

Imagine the most intense armchair quarterback you know, the guy who lives and dies by how the Detroit Lions fare in the NFC North standings. Now apply that same fanatic energy to getting into a famous college. That’s the vibe.

And to really drive it home: a 37-year-old husband and father of almost four kids having a New Year’s resolution of "no career planning" is wild. It’s as alien as a dog laying an actual egg.

Getting here wasn’t easy. From the moment I considered this resolution, I started trying to convince myself it was a good idea. Over and over, I hashed out the same conversation: justifying why I wasn’t setting goals that would lead me to become a CEO or senior-level elected official. It’s that same old churn—resisting the achievement-addicted version of me who’s always craving that ever-elusive gold star.

But every time I pushed back against the addict within, he pushed right back.

Then, it hit me.

That addict is a ghost. He’s not here anymore.

I’ve made decision after decision that shut the door on becoming a CEO or a senior-level elected official. The life he wanted for me? It’s long gone. That window closed when I decided not to move to DC after college, when I stayed local for grad school, and when Robyn and I built our big, beautiful family.

That ghost has no power anymore. The dream he clung to isn’t even viable.

And yet, there I was—arguing with him. Justifying to this phantom why I don’t need to chase some mirage of a dream. I’d been sitting in an empty room, at an empty table at the center of my mind, negotiating with nobody.

Once I realized this, I knew it was time. Time to stop having the same damn conversation, over and over, about the direction I want to take my life. Time to stop justifying my decisions, explaining why I’ll never live up to that ideal I once clung to—that I was only worth what I achieved.

The only thing left in the room was the ghost. And when that happens—when the demons are put to rest—there’s only one thing left to do: say, “Thank you for your time, but this negotiation is over.” Turn off the light. Close the door behind us.

The most important thing I learned this year was this: at some point, you stop negotiating. You thank the ghost for what it taught you, but you leave it behind. Because joy isn’t found in rehashing the past—it’s waiting for us in the life we’re living now.

Developing courage in the new year

Courage is the king of all virtues. Developing it on purpose can make a huge impact on our own lives and on the people we seek to serve.

As it turns out, developing courage in ourselves is not so easy. We have to learn it by practicing it. There’s no YouTube video (that I’ve found at least) that we just have to watch once and suddenly become courageous. Reflection and introspection is the best method I’ve found so far (and that’s not particularly easy, either).

In lieu of a New Year’s resolution like running a marathon or reading 20 books, I’ve opted to commit to a practice which I hope helps me to cultivate courage.

In hopes that it’s helpful, here It is:

First thing in the morning, answer these two questions in notebook, quickly:

What do I think will be one of the hardest things I have to do today?

How do I intend to act in that situation?

Last thing at night, answer these two questions in notebook:

What was actually the hardest thing I had to do today? Why was it hard?

What should I do differently next time?

I’ve been on the wagon for about 6 days now. Here’s what I’ve learned so far:

Even considering what’s going to be hard, helps me to have a plan. That makes me feel more confident and courageous in the moment

Debriefing and learning from the hard stuff yields benefit quickly, sometimes even the next day

I’m really bad at predicting what the hardest part of my day will be, which is humbling. I’m excited to review the data in my journal after 2-3 months because I suspect it’ll reveal some blind spots I have in my life

Here’s the background on why courage matters so much to me, and why I’m so interested in trying to cultivate it in myself and the organizations I’m part of:

The first obstacle to being better at anything is laziness. If we don’t get off our behind, we can’t figure out the easy stuff. This is the case for being a better spouse, parent, citizen, athlete, accountant, corporate executive, chef, team leader, musician, change agent, or gardener.

Any domain has fundamentals that are easy to learn, but just take work. We’re lucky that in our lifetimes this is true.

Before things like youtube, google, and the internet more generally I suspect it was much harder to learn the basics of anything - whether it was baking bread, grieving the loss of a loved one, personal finance, or designing a nuclear reactor. But the obstacle of laziness remains, if we don’t get out of bed we don’t get better anything.

Eventually, however, the easy-to-learn-if-you-do-the-work fundamentals are already done, because we, correctly, tend to do those first. At that point, all that’s left is hard. So we have a choice: do the hard stuff, or stop growing.

As I’ve gotten to the age where all that’s left is hard or really hard, I’ve become more and more interested in courage. Courage, as I define it, is the ability to attempt and do the hard stuff, even though it’s hard. For this reason courage, to me, is the king of all virtues: it helps us to do everything else hard, including building our virtues and character.

This is a broadly applicable skill because there are all sorts of hard things out there: technical challenges, situations requiring patience or emotional labor, bouncing forward through adversity, product innovation, leading others through solving complex problems, being vulnerable, managing large projects, having a happy marriage, being a parent…the list goes on.

Courage matters, because it is fundamental for us to even attempt the hard stuff once the low-hanging fruit in our lives is gone. Although it is non-trivial, developing courage in ourselves and our organizations matters a lot and can make a huge difference for ourselves and those we seek to serve.

Something more compelling than fear

I don’t want to live in a fear-driven culture for the next twenty years. I’ve grown tired of it.

It seems to me that “know thy self” is good advice to end an attachment to fear. If we have something more compelling to focus on, we have something to think about that’s more compelling than the fear others are trying to project into our lives.

Twenty years is the time a newborn child needs to come of age. For children born on September 11, 2001 that day would have been yesterday. Those children have come of age.

I remember feeling a placeless and faceless fear, frequently, over the past twenty years. Fear of terrorism, the competition of globalization, or the fear of death. Or the fear of missing out. Or the fear of racial tension, polarization, and social shame. The fear of being canceled or having to stand alone.

It seems to me, that fear was a recurring motif of the past two decades. These children have come of age in a time typified by its focus on external threats, assertion, and outrage. It gives me a weeping, grieving, sadness to think that they, those children, and we those others, have lived under twenty years of siege by a culture enmeshed with fear.

I do not want the next two decades to be a response to fear.

But how?

—

Apparently, there is a YouTube channel where classical musicians listen to K-Pop and comment on its musicality. An analytically-inclined colleague of mine told me about it when we were chit-chatting before a virtual meeting - about how she loves ballet and played the viola growing up. This YouTube channel uncannily blends three of her passions: classical music, analysis, and K-Pop.

It was one of those moments where everything feels light and elevated because you’re in the presence of someone who feels comfortable in their own skin. It was liberating to just listen to her talk about those interests of hers, because she was being her full self.

Know thy self. We have so many expressions in the western world that riff on this wisdom: having a North Star, stay true to yourself, stick to your knitting, be comfortable in your own skin, you do you, etc.

It seems to me that being confident in who we are, and what we like, and what we stand for, is the first step in getting out of a cycle of fear. Because if I have something inward to focus on, I don’t have to focus on an outward threat. It’s like knowing yourself gives us our mind and soul something better to do than look at the scary things around us.

Talking to my colleague reminded me of this important practice of knowing thy self.

But how?

—

I have told myself lies. Like, big lies that led me astray of who I am. Those lies wasted my time and talent; kept my soul and mind in chains.

By bringing these lies into the sunlight, they become less infectious. And then, knowing ourselves is more possible. And then we have something other than fear to anchor our lives in.

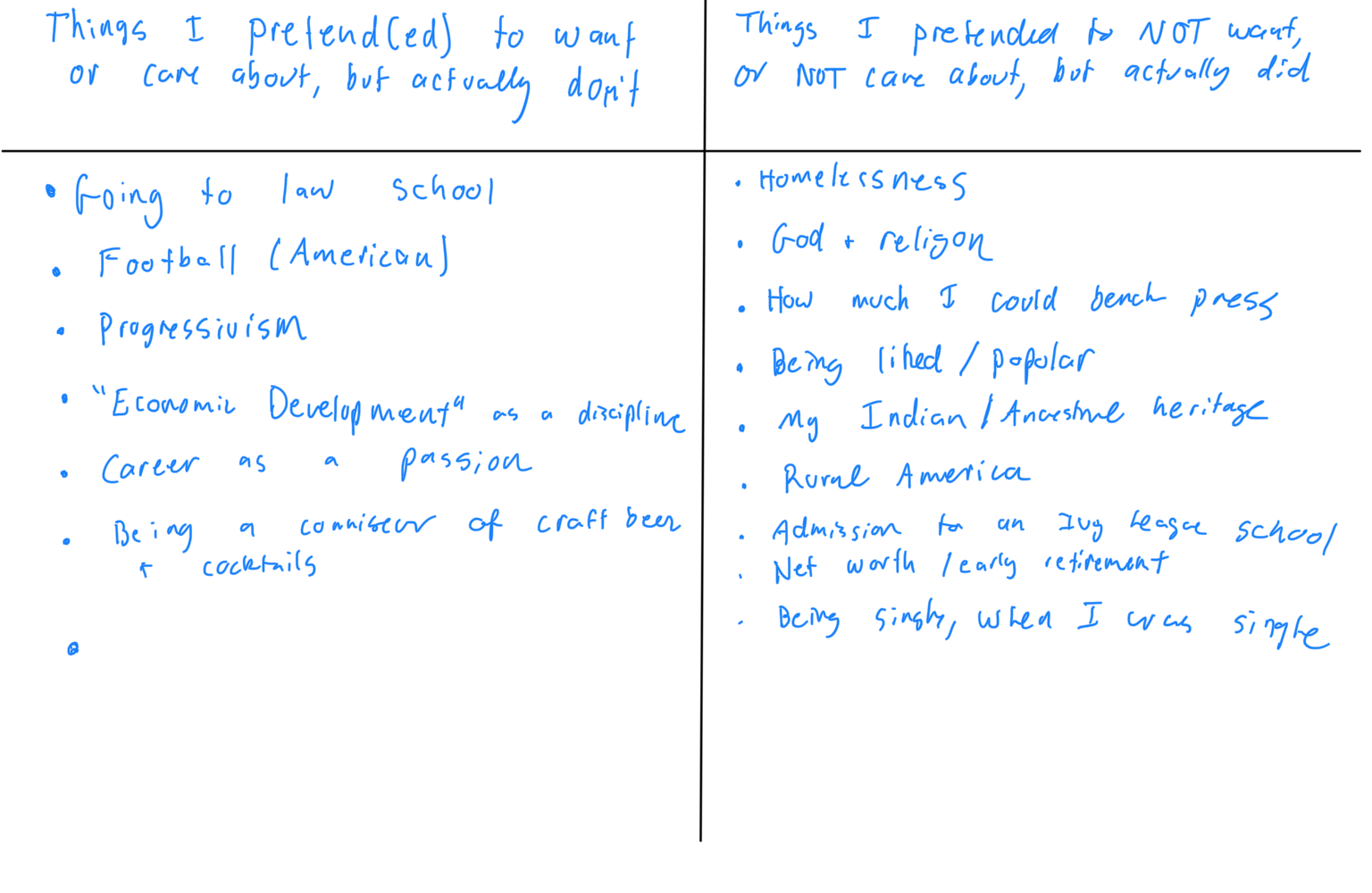

Reflection to disinfect the lies I tell myself

1. Make a two column table on a blank piece of paper

2. Label the first column, “Things I pretend(ed) to want or care about, but actually don’t”

3. Label the second column, “Things I pretend(ed) to NOT want, or NOT care about, but actually do”

4. Answer it honestly

5. Share with someone who knows you better than yourself. Ask them: “What am I still lying to myself about?”

6. Do something different.

Snapping out of social comparison

I snapped out of the LinkedIn doom loop by thinking about the sacrifices a counterfactual world would’ve required.

When I’m stuck in a rut of feeling like I don’t measure up to others’ accomplishments, the advice of “remember how lucky you are” or “don’t compare yourself to others” or “focus on being the best possible version of you” just doesn’t work for me. It never has.

And in general I suppose those are good pieces of advice. They just don’t help me get out of a cycle of comparing my accomplishments to the people I went to school with or am friends with on LinkedIn.

Most Saturdays, these days at least, we go on a family walk. We live a few blocks away from a neighborhood coffee shop and we go after breakfast. Bo gets a hot chocolate with whipped cream, Robyn gets a coffee with milk, and I treat myself to a mocha - it is the weekend after all. Riley gets a extra long walk with extra time for smells and Myles is content just looking around and feeling the breeze go by as he rides in the stroller’s front seat.

And today, instead of trying to convince myself to stop feeling down about not being as accomplished as my peers, I started to wonder about trade-offs. After all, I made choices - for better or worse - that led to the spot I’m in today. And I wondered, if I had made different choices, what would I have had to sacrifice?

And I quickly realized, if I had made different choices that led to more professional success (which is mostly what drives my feelings of insufficiency, relative to my peers) I would’ve probably had to give up two things: living in Michigan and being a present husband and father. Which are two sacrifices I was absolutely not willing to make.

More or less, this was the thought exercise I went through:

And sure, after doing this exercise there were a few things that I regret and would do differently, like working harder on graduate school apps or sacrificing some of house budget for lawn care (I am irrationally embarrassed about how much crabgrass and brown patches we have on our lawn).

But by and large, thinking about the sacrifices making different choices would’ve required helped me to snap out of the doom loop of social comparison. Trying to ignore the feeling of not measuring up never works. Think about sacrifices and trade offs, was remarkably helpful.

If you also struggle with measuring yourself up to others’ accomplishments, I hope this reframing of the question is helpful to you too.

When I’m feeling used up

How I respond to feeling used up is a choice. It’s a choice. It’s a choice.

As a general rule, I don’t advocate for myself. It’s not that I avoid it or find it uncomfortable, I never really think to do it. The reason why, making a long story short, is that I’m a people-pleaser. I’m motivated more by making someone’s day than I am by a feeling of personal accomplishment.

To be clear, this is a personality flaw. Because I am a people-pleaser, I end up feeling used and used up a lot. Other people ask for my time and energy and my default position is to say yes, which leaves me feeling depleted.

This is a choice, with trade-offs.

How I respond when I feel used up is also a choice.

On the one hand, I could start saying no. I could protect my time and energy by setting boundaries.

On the other hand, I could insist upon reciprocity. Doing so would make day-to-day life more of a give-and-take rather than a mostly-give and sometimes take.

And seemingly paradoxically, I could give more. By digging deep and giving more, I could practice and get better at expanding the boundaries of my very little heart, and learn to give without receiving just a little more.

In reality, I should probably do some amount of all these things. Honestly though, I hope I don’t have to set boundaries or insist upon reciprocity. I hope instead that I can dig deep within and give more when I feel used up. I hope I’m dutiful enough to give to others, even if it means bearing more weight and sacrificing status or personal accomplishment.

I don’t know if the sinews of ethics and purpose holding me together can sustain that. I am definitely a mortal man, and not a saint. But still, I hope that I can dig deep and give more. It seems to be the choice most likely to create the world I hope to live in and leave behind.

But the revelation here is that it is indeed a choice. I feel so much pressure from our culture that the way to handle feeling used up are things like, “say no” or “self-care” or “manage your career” or “give and take” or “know your worth”.

And all that probably has a time and a place for mortal men like me. But that’s not the only choice. This choice is what I’ve found comforting.

Another way to handle feeling used is to live by wisdom like, “service is the rent we pay” or “nothing in the world takes the place of persistence”or “no man is a failure who has friends” or “be honest and kind” or “the fruits of your actions are not for your enjoyment”.

How I respond to feeling used up is a choice.

Common bonds and unity that endures

The Hindu priest that married Robyn and I - to be clear, we were married twice: once by a Catholic priest, once by a Hindu pandit - left us with simple advice that we still remember and recite often:

From now on, you must be Together, Together, Together. Remember, Together, Together, Together.

From that day, Robyn and I were united in marriage.

But to be honest, I usually find myself wanting more when I hear the word “unity” uttered. Unity, to me, is a hollow word unless the common bond it invokes is specific and salient. Unity for what? Around what purpose? For whom? Unity bound by what beliefs?

In our marriage, and in the marriages of the people that we are close enough to see their marriages up close, I would say the beliefs that bind them are specific and salient. Here are some examples from our marriage:

Our vows: to love, honor, and cherish each other; for better or worse; for richer or for poorer, in sickness and in health, good times and in bad, until death do us part

Our common beliefs: belief in God; that we put family first, but that our marriage ultimately exists to serve others

Our common dreams: to grow old together, to grow a family and stay close to our international extended family, raise our children to be good people, to learn through travel, and be enmeshed in a community throughout our life

Our common experiences: the trips we’ve taken; the dates we’ve been on; the time we’ve spent doing nothing but enjoying each other’s company; the suffering we’ve navigated together; the little moments every day where we affirm, support, respect, and acknowledge each other and the investment of love all those moments - big and small - represent

If you’re a married person ( or expect you will someday) I do suggest trying to do a similar exercise where you specifically write down what the common bond that undergirds the unity you have with your spouse. I honestly had never done this until just now and I feel washed over with warmth, confidence, stability, and love.

I think this exercise is worth doing for more than just marriages. Any team or community that wants to endure also requires a durable common bond that is specific and salient. Asking the question “what unites us?” is just as relevant to companies, communities, and even states or nations.

The real hum-dinging implication, though, is how. How do we discover and articulate our common bonds? How do we create and nurture our common bonds? It’s not useful to merely describe that we need common bonds to have unity - that’s obvious. The very difficult question is how.

I’m planning a few posts over the next 4-6 weeks that push this idea of unity and the “how” of it further. But here’s a start: I think a good place to begin is interrogating our own beliefs, and asking what do I believe?

There was a terrific series some years ago that National Public Radio launched called This I Believe. The premise was simple: ask people to articulate their most core beliefs and then share them publicly. And when you hear some of those essays, you don’t just understand others’ beliefs cognitively, you feel and internalize them. We could all stand to write one of those essays and share it with the people we are close to.

Because after we understand our own beliefs, our next job - and I think it’s the harder and more important one - is to listen and deeply understand, feel, and internalize the beliefs of others.

And from there, we are well on our way to articulating our common bonds specifically and saliently - and developing a unity that is durable and enduring.

The One-way Door

At some point in the past five years, I accepted that the door Papa went through went one way.

It’s been five years since Papa went through the door.

In five years, a lot of life - our marriage, Riley, buying a home, changing jobs, a trip to India, a trip to Frankenmuth, family dinners and washed dishes, backyard barbecues and park walks, Bo’s whole life, Myles’s whole life, 5 Diwalis, 5 Thanksgivings, 5 Christmases, the Trump Presidency, a pandemic, two half marathons, knowing God again, a mostly written book, and many many moments of laughter and tears - has happened.

And for a long time, I knew he had already left. But, still, I thought he might come back through that door. Not in a real way, but in a fantasy sort of way. Like, in a waking up from a dream or being on candid camera sort of way. For a long time, a little part of me was holding onto the only-with-a-miracle possibility that he’d be back.

I don’t know exactly when, but sometime in the past five years I let go of that hope. I knew and thought he wouldn’t be coming back. Finally, I accepted that it was a one-way door.

And so what to do? It is true, the door is one way. And one day, I too, will head through it. That is certain. This is all certain.

Basically all of us have this predicament at some point in our lives. We have to accept that it’s a one way door, and choose what happens next. Do we sit and wait in a chair by the door, biding our time until our turn comes? And then, relief, because we have rejoined our loved ones who have already gone ahead?

Or, do we build a life on this side of the one-way door? Do we make memories and hang those pictures up beside it? Or cover the door in crayon drawings and finger paint? Do we build a table and cook and feast to celebrate life on this side of the door? Do we laugh and cry and yawp and run and play and blush and garden and read and mend things?

I feel guilty, often, for trying to build a life without him on this side of the door. Even though I know it’s not betrayal, I think it is. I know living life is what he would make me promise to do had he known he was going, but I still think something’s not right about it. I may never rid myself of this dissonance. I don’t know.

But the door no longer haunts me, on an hourly and daily basis like it used to. It’s pain that’s chronic and manageable, not acute and insufferable. But here I still am, five years later, torturing myself by reliving memories of his last days, while weeping tears of gratitude for the life we have now. And still, thinking of him, praying, and wondering how he is on the other side of the door.

Radical Questions, Radical Diversity

By asking questions on facebook, I’ve learned the value of radical diversity and radical questions.

Over the holiday, my father-in-law asked me a very interesting question along these lines: after asking questions on facebook for so long, what have you learned?

Over these past five years or so of asking an almost-daily questions, I’ve tried not to ask gimmicky or empirical questions. I’ve tried to ask simple, specific questions that require reflection and emotional labor. This is not for any special reason, I just I think those sorts of questions are most interesting and yield the most wisdom on how to live a good life and be a good person.

What has been surprising is how often someone says something incredibly perceptive and relevant. Like, nearly every response I’ve ever received to any questions I’ve ever asked is something valuable. Individually, everyone has something profound to contribute.

At the same time, I’ve come to realize how deep but narrow of an understanding each of us have about the human experience. Nobody’s perspective fully explains or grasps the full truth on how to live a good life or be a good person. We all have a fragments of it. We all have a remarkably clear understanding on the little piece that’s been made clear to us by virtue of our most unique and compelling experiences.

If the truth of life were a large tree, we are not photographers standing from afar that can see the whole tree. Rather, we are each little birds that understand just the leaves and branches right around us.

Which leads me to two big takeaways - to understand the big truths of our human experience we need radical diversity and radical questions in our lives.

RADICAL DIVERSITY

The importance of diversity in teams trying to solve complex problems is not a new idea. Scott E. Page (Go Blue!) has done fascinating research in this area. I loved his book on the topic, The Difference: How the Power of Diversity Creates Better Groups, Firms, Schools, and Societies.

But what I would say, is that diversity isn’t just important for team problem solving. To understand the tree of human experience we need radical diversity in our live so that we can learn about the far reaching parts of the tree we’re all in, so to speak. Like, we don’t just need to learn from people who are different from us, they need to be radically different, from branches on the tree that are far, far away from us.

For example, there’s just some things that drug addicts understand better than others. Straight up. Or people who have lost parents early in life. Or people who have been bullied. Or people who have been insanely wealthy or dirt poor. Or people who have lived abroad. Or people who’ve had to execute massive projects. Or people who’ve studied the arts. Or people who have built things with their hands. Or people who have been abused. Or people who have raised children. Or people who have lied or have been lied to. Or people who have been to space. Or people who have served the most vulnerable. Or people who grew up in most typical suburbs. Or people who have been farmers. Or people who have committed heinous crimes and returned from prison.

Or whatever radical experience it is. There are just some things that folks who have had certain kinds of radical, intense experiences just understand better than I do. To really understand the human experience, I can’t settle for knowing people who are different than me - I have to learn from people who are radically different than me.

RADICAL QUESTIONS

At the same time, I will not learn much about the human experience, even if I have radical diversity in my life, if I only talk to those people about topics like the weather, sports, politics, or celebrity gossip.

To learn about human experience we have to talk about the radical things that have happened to us, which means we have to ask radical questions.

I don’t claim to be great at this yet, but I have learned a lot on how to ask good questions. And radical doesn’t mean sensational. It means questions that are reflective and require emotional labor.

And yes, I’d suggest that those sorts of questions are indeed radical. Because honestly, the bar on asking radical questions is really low. Even though the questions I tend to ask aren’t extremely radical most of the time, it’s easy to clear a very low bar.

Most questions that we’re ever asked in our day to day lives are boring and sanitized. Think about every customer feedback survey you’ve ever taken: boring. Think about every question asked during a panel discussion you’ve attend: boring or loaded with assumptions. Think about every question you’ve ever talked about chit chatting at a bar or waiting in line somewhere: boring or safe.

There are so few forums where we ask or are asked questions that require reflection or emotional labor. And so, all we ever learn about is our little twig on the tree of human experience, even if we’re surrounded by radical diversity.

And I’d also say that it’s not that scary to ask a radical question, though it may feel that way. If you haven’t, you should try it sometime.

We are so deprived of radical questions in our lives, I’ve found that many people seem to feel liberated when asked a radical question. We’re just waiting for the opportunity to share something radical, if we believe we are listened to, safe, and respected.

Radical listening and radical love in settings of radical diversity lead to radical answers to radical questions.

I think most people, at least my age, care about this wisdom of how to live a good life and be a good life. We can help each other do this. We really can.

Dreams, from joy and the conviction of their own souls

Why, exactly, did I have the dreams I ended up having?

Raking leaves is one of those chores I don’t want to do until I’m doing it.

Until I’m with rake in hand, I’ve forgotten the crispness and soft chill of the air, and the sound of the brushing leaves. It’s sweatshirt weather. But I also forget that sweatshirt weather is also “thinking weather.”

As I raked yesterday, I escaped to thinking about dreams. And my subconscious drew me not to thinking about what my dreams are, but rather, “what influenced me to have the particular dreams that I do?” And for me, so much of my dreams are wrapped up into my parents’ dreams for me.

To be a “big man” or a man of great community respect. And I wondered why they had those dreams for me, and I think it must have been, at least in part, because of how they were treated when they arrived in this country. As immigrants, I don’t imagine they ever felt accepted or welcomed, at least for the first few decades of their arrival.

And when you’re an “outsider” respect and wealth protects you from harm - whether that is rude service or dirty looks in public, or more unfortunately, a brick through your window. I imagine my parents’ pain is something that influenced me to want the dreams that I wanted early in life. Pain is a powerful influence.

But my dreams were also influenced by the broader culture whose collective opinion skews toward a hedonistic, lowest common denominator and accepted malaise . Let’s call those the dreams of “the herd”.

The herd wants me to hold its dreams as my own, because it’s a mechanism of justification. It’s harder to criticize the herds hedonistic aspirations if they convince me (and others) to be part of it. The more people the herd co-opts, the more their dreams - however dishonorable they may be - become normal. Just like pain, the herd is a powerful influence.

So early in life my dreams were influenced by two things, avoiding pain and succumbing to the herd’s mentality. That’s where “I want to be a Senator” or a “social entrepreneur” came from - those were two dreams that pain and the herd led me, specifically, to.

And I’ve let go of those dreams, not because I grew out of those dreams, but because I grew out of pain and the herd’s mentality. Mostly through luck and blessing, some very special friends and family helped me to discover joy and my own soul. It’s a journey less like climbing a mountain, and more like a long, lonely walk.

It’s a journey I am still on, but my dreams are now about a growing family, goodness, the honor of public service, and sacrifice for a community bigger than myself. I still fall into the traps laid before me by pain and the herd, I am after all a mortal man. But these dreams - borne of joy and what lies within the core of me - are a far cry from the version of myself that was nakedly ambitious, longing to be on the Crain’s 20 in their 20’s list.

Honestly though, the point isn’t about me, nor should it be.

The point is this: I can only hope - for our children, and the children of our friends, family, and neighbors - that the generation up next spends less of their life having their dreams influenced by pain and the herd than I did. I hope, deeply, that more of their dreams, and really their lives, are instead influenced by joy and the convictions of their own soul.

Keeping Up With the Joneses or Answering Hard Questions?

The cycle of how life is supposed to work has always been presented to me like this, since I was a kid:

How we keep up with the Joneses

Get the best grades and build the best resume you can in high school

Get into best college you can

Get the best grades, network, and internships you can in college

Get the best, most prestigious job you can in your twenties

Get into the best graduate or professional school you can

Get the best placement you can and rise the ranks to the highest-paid and prestigious post you can

Have kids and move into the best neighborhood with the best school system you can

Repeat this process again and help your kids be the “best” they can be, so they too can keep up with the Joneses

I used to think this cycle kept on going because humans had some need for domination and power, status, or both. As in, we had this evolutionary need to be “the best”.

But after having a very insightful conversation this week, I wonder if using the tried and true MO of keeping up with the Joneses is attractive because it’s simple.

One of my best friends has been thinking about meaning and shared a remarkable insight with me. My friend said it better, but here’s the essence:

Life is messy and there are these difficult but inescapable questions we’re confronted with - about life, death, meaning, and purpose. These questions are exceptionally hard and scary to answer. And it’s not fair that the only people who seem to really have consistent help with these ineluctable questions are the religious and the pious. What about everyone else?

It had never occurred to me that so many of us may get stuck in a cycle of keeping up with the Joneses, not because we’re nakedly ambitious or because of social pressure. Maybe it’s just the easiest, most obvious way to feel like we’re not wasting our lives or doing what we’re supposed to.

Confronting life’s ineluctable questions (my friend used this word in her essay, I had to look it up, but I’m using it here because it’s a perfect word for this context) is so hard and intimidating to do.

Keeping up with the Joneses has its own drawbacks, but it’s less risky than confronting ineluctable questions.

How we keep up with the Joneses is clearly defined and relatively unambiguous. Society doesn’t flog anyone who tows the line and just keeps up with the Joneses. Our institutions (colleges, schools, corporations) all reinforce these norms too. Keeping up with the Joneses is not exalted but it’s rarely rejected. In the realm of figuring out how to live, it’s the path of least resistance.

But I worry that there’s an intergenerational debt accumulating here. If we repeat this cycle of keeping up with the Joneses - generation after generation - will we eventually forget how to tackle life’s ineluctable questions? If we do forget, is that really the type of culture we want to leave to our grandchildren’s grandchildren?

For me, the answer to that question is absolutely not.

I am determined - 2020 will not become a hashtag | Hurricane-proof Purpose

A note about 2020, algorithming ourselves to find our individual higher purpose.

I am determined not to let this year, 2020, become a hashtag. Every time I hear the punchline of a joke or a meme end in something like, “well that’s 2020 for you” I cringe. To me it’s defeat. It’s a resignation that we do not have agency over our own fate, or at least our reaction to our fate. I am determined not to let 2020 become a hashtag, even if it’s just in my own head.

In most instances, this is where I’d insert an “easier said than done”, but I don’t think so. It’s actually very easy to bounce back from a “that’s 2020” mindset. All it takes is focus on a higher purpose.

If a higher purpose for my life is clear, then all I have to do is focus on that purpose. And just consistently think about that north star purpose and work on that. Focusing on that pre-established higher purpose pushes all of 2020’s qualms - both the legitimate trauma this year has brought, and the whining too - out of my mind.

The key is that purpose can’t be petty, shallow, or ego-driven. It has to be deep. It has to stir to the core. A higher purpose is only higher if it can withstand the hurricane times, like the ones we are living in. 2020 is not the hard part, building a hurricane-proof purpose is the hard part.

For me, that purpose falls into two parts - one related to my private life and the other related to my public life. I have been thinking about this for years, I think, and it’s starting to become clear. But my personal purpose is a bit beside the point right now. What really matters is, “how?”

Three friends of mine, Alison, Glenn, and Nydia, were among a handful that sent me some transformative comments to an early draft of a book I’m writing. Their particular comments pushed me on this point: the difficulty in living a purposeful life is not just living it consistently. That is hard, but how do we even figure it out? What’s the mental scaffolding we can lean on?

I have much more thinking and writing to do on this, but where it starts, for me at least, is being really good at noticing things. And luckily our mind, body, emotions, and perhaps even our soul are very sensitive instruments for finding these purpose-fulfilling moments if we calibrate them properly. Just listening to our mind, body, and gets us pretty far. But for that to work, we have to know how to listen and what we’re listening for.

Step one, I think, is calibration. Perhaps a good exercise is thinking of 5 or 10 instances where you had very strong emotions or were deeply immersed in thought. Maybe there are a couple of moments that you think about obsessively, even though they were seemingly small.

And when I think about my 5 or 10, some of them are self-indulgent feelings. They are times when I had a strong emotional reaction because of external affirmations, power, recognition, and ego. Throw those times out of your sample, they are false positives. Those aren’t the moments that lead to a discovery of higher purpose, in my experience. Rather, those are the moments that have taken me in the precisely wrong direction.

And then, remember those remaining moments vividly in your mind. Really feel them. How would you describe those feelings? Let your guard down, and let the deep feelings of peace, joy, or courage flow through your body. Try to amplify the feeling until you feel it in your torso or your limbs. Get to cloud nine. Go higher. Get to the place where you know in your bones that something about this memory is related to a hurricane-proof purpose. This feeling is your filter to exclude the memories and experiences that are false positives.

Step two, I think, is adding data to your dataset. Think of all the times where you feel similar feelings of deep emotional courage, peace, and joy. Think of all the times where there was something that stirred in you nobly. Think of all the times you felt flow or a state of pure play. As you go through your day, take a pause if you feel the beginnings of those feelings.

Organize these moments in your mind, write them down if you have to. Get as many data points as you can, being careful to separate out the moments that are simply ego-boosters and not examples of the deep, purposeful stirrings we’re looking for. Try to filter out the false positives.

I find zen meditation techniques to be helpful practice for getting better at this type of noticing.

Then explore the data and find the patterns. Talk about it, journal about it, do whatever you have to do. Slowly, the right words to describe purpose emerges. And then it changes as you get more data. And as you get more data, your filter gets better too. It’s very bayesian in a way.

This post became something much different than I originally intended. Whoops.

But the point is, I am personally determined not to let 2020 become a hashtag. The best antidote I can think of is focusing on a higher purpose. It’s easy to say go do it, so these reflections are the best advice I have to offer, so far, as to what that higher purpose may be for you.

I don’t know what help I can be, but please let me know if you think there’s something I can do to support you if you’re on this type of journey. It’s kind of like applying an algorithm to ourselves and what we feel.

Turning my inner-critic into a coach

Reflection changed my relationship with my inner-critic.

My inner-critic and I have a long, quarrelsome history together. He (my inner-critic is male) was a jerk for a really long time.

He started coming around in middle school. He told me that I should be afraid, especially of talking with girls I had pre-teen crushes on. And then he made me feel terrified of failure in high school. He led me astray in college by making me try to fit the cookie-cutter mold of pre-law, even though I didn’t want to.

Then as a young adult, he reminded me how lonely I was, and rubbed my nose in how I didn’t have a graduate degree or a high enough public profile. He made me feel like garbage about how little I was dating and how I needed to be more elite (his opinion, not mine).

Then, on top of all that - as I approached my early thirties, he scared me into thinking I was not good enough at my job or getting promoted fast enough. When I felt like doing something difficult, unorthodox, or unexpected he naysayed me, “naw you shouldn’t do that, that’s not for you to do” he would say. He also told me, so often, to take instead of give, indulge instead of restrain, ignore instead of love.

Over the course of years he has shamed, scared, cajoled, and ridiculed me. Like I said, he was a jerk for a long time.

I write often about reflection because I think it’s really important. Reflection is the engine that drives learning from experience. I’ve been developing a practice of structured reflection for over 15 years now, and I’ve been working on a project to share what I’ve learned. Reflection is what I’m probably best at and most serious about.

What I’ve realized in the past week, is that reflection is more than just the abstract notion of “learning from experience.” In retrospect, reflection has been a process that has improved my relationship with my inner-critic at least ten-fold. Reflection has transformed my inner-critic and made him into a damn good coach.

This is why I’m becoming something of an evangelist for developing a practice of structured reflection, similar to how someone might run, lift weights, do yoga, pray, or meditate. Almost everyone I’ve had a heart-to-heart conversation with alludes to their inner-critic and how terrible theirs is to them, too.

We all have to manage our own critic, and it seems more useful to channel them rather than silence them.

But how?

Structured reflection - over the course of time - was sort of like having a crucial conversation along these lines, with my inner-critic:

Alright buddy, our relationship is not working out. We need to do something different. You can’t harass me anymore. You’re either going to help me get better, or I’m going to replace you with someone who does.

Here’s a piece of paper with what I believe and how I want to be better. This is what you’re going to coach me to do.

I need you to coach me hard. I need you to be honest, specific, and encouraging. Sometimes, I’m going to need you to give me tough love and tell me hard truths. I understand that. But you will not make me feel like shit and shutdown while you do that. I need you to push me to be the highest version of myself. I need you need to be my coach, not my critic.

You will not heckle me right before I take a leap and do something hard, that we’ve agreed is important to do. In turn, I promise to work hard during practice and listen to what you coach me to do. The only way this is going to work is if we have a symbiotic relationship. need you to get better and you need me because you’ll have nothing to do if I shut you out.

Do we have an understanding?

I did not intend for this to happen when I started to get really serious about practicing reflection. But in retrospect, working through a structured set of reflective prompts and practicing them religiously has given my inner-critic no choice but to become my coach.

Thanks to two friends - Alison and Glenn - who connected some really important dots in my head on this subject. They probably don’t even realized they gave me that gift.

Visualizing the Highest Version of Ourselves

A thought experiment, just like an athlete would do to visualize their peak athletic performance.

I feel so many pressures to “be” very specific, culturally-prescribed, things. Be productive. Be smart. Be professional. Be loving and kind. Be pious. Be cool.

And being all these things is so confusing, because being one seems to conflict with another, much of the time.

Lately, I’ve wondering if I could stop trying to be something specific and try to just be the highest version of myself. Paradoxically, maybe trying to be the best of everything would actually be liberating.

And that’s when this thought experiment came to be. Like an athlete visualizing peak performance in their sport, what if I picked a specific environment in my day-to-day life and just visualized being the “highest” version of myself? It could be in a meeting at work. When with my family on vacation. When running. When mowing the lawn. Doesn’t matter - it could be any environment.

In any environment, what if we tried to imagine the highest version of ourselves? Would we be more likely to live up to it? Would the process change us? Would we be more or less frustrated at ourselves?

I didn’t know, so I gave it a try. I don’t think you need to read my reflection (below), unless you want to. I include it only to illustrate what I mean.

What I will say is this, I did this on a whim, just to see what would happen. And I don’t know what will happen in the future.

But after I did this thought experiment (in italics below), I had a tingling feeling in my lower abdomen. Not the queasy stomach feeling, but the kind of tingling you feel when you are about to give someone a gift on their birthday. Or the butterflies you get at the last step before solving an equation in math class. Or when the curtain goes up at the theater.

If you want to, give it a try. Just take the sentence below and replace what’s after the ellipsis with something relevant to you. I hope you get the same warm, tingling feeling if you try it for yourself.

I close my eyes as I type this, and push myself to imagine the highest version of myself in a typical situation…in this case when eating dinner, with my family, on a week night, 12 years from now.

I am at the dinner table. Specifically, our dinner table at home with my wife and kids. It is about 12 years from now - say in 2032. We are eating tacos, the same way we have every other Tuesday for nearly 15 years. It’s early autumn. We all sit quietly and pass our dinner around the table, everyone taking a turn. We are light and easy and comfortable feeling, because we are home. Robyn is laughing with one of the boys about a new joke they heard from a son’s friend on their way home from school - Robyn had pickup duty today. I laugh as I put a dollop of sour cream atop a small mound of avocado. Even though I am assembling a taco, I’m paying close attention to everyone. I look up, giggling at the joke.

I scan the room with my eyes only, this is my opportunity to check how everyone is feeling. If they are laughing as they normally do, all is well. I see our other son crack a smile but he doesn’t laugh. Hmm, how unlike him.

I quickly look down at everyone’s plate. Normal, normal, normal, hmm. Our same son, the one that didn’t laugh didn’t take as many tomatoes as he normally does. How unlike him. I sit up straight and start my meal, keeping him in the corner of my eye softly.

We do our nightly ritual of catching up on the day, and we do our “highs and lows”. My son seems to be his normal self, but his eyes are wandering a little bit. There’s something distracting him. I decide instantaneously that I should try talking to him after dinner. I mentally note that and focus my attention back on the entire family and our meal, so I don’t disengage myself.

As we start to break from the table, I ask, “Son, could you help me store the dog food? It’s a pretty big bag and my wrist still hurts from playing tennis yesterday.”

I probably could store the dog food myself. But my wrist IS still sore and I want to create the space for him to open up.

I ask him as he opens the container, “So bud, what have you been thinking about lately?” As he pours the kibble into the bucket, he starts to talk. He mentions a friend off-hand and how he had to cancel on their weekly study session.

I see my opening, but I opt not to take it. Instead I say, “Hey bud, since you’re already over here would you mind helping me load the dishwasher?” When he agrees, I smile extra wide and say thank you.

We chit chat the whole time. Just as we load our last plate, my son pauses, seeming to collect his thoughts. And then he hesitates. I wait . Then I gently raise my eyebrows to let him know that it’s his turn to speak if he wants to.

He takes my cue. Then he says, “Hey papa, have any of your friends ever avoided you?”

I take a moment, and pour two glasses of water. I motion him over to the now spotless dinner table.

“Yeah bud, sometimes. Let’s relax for a minute and I’ll tell you about it.”

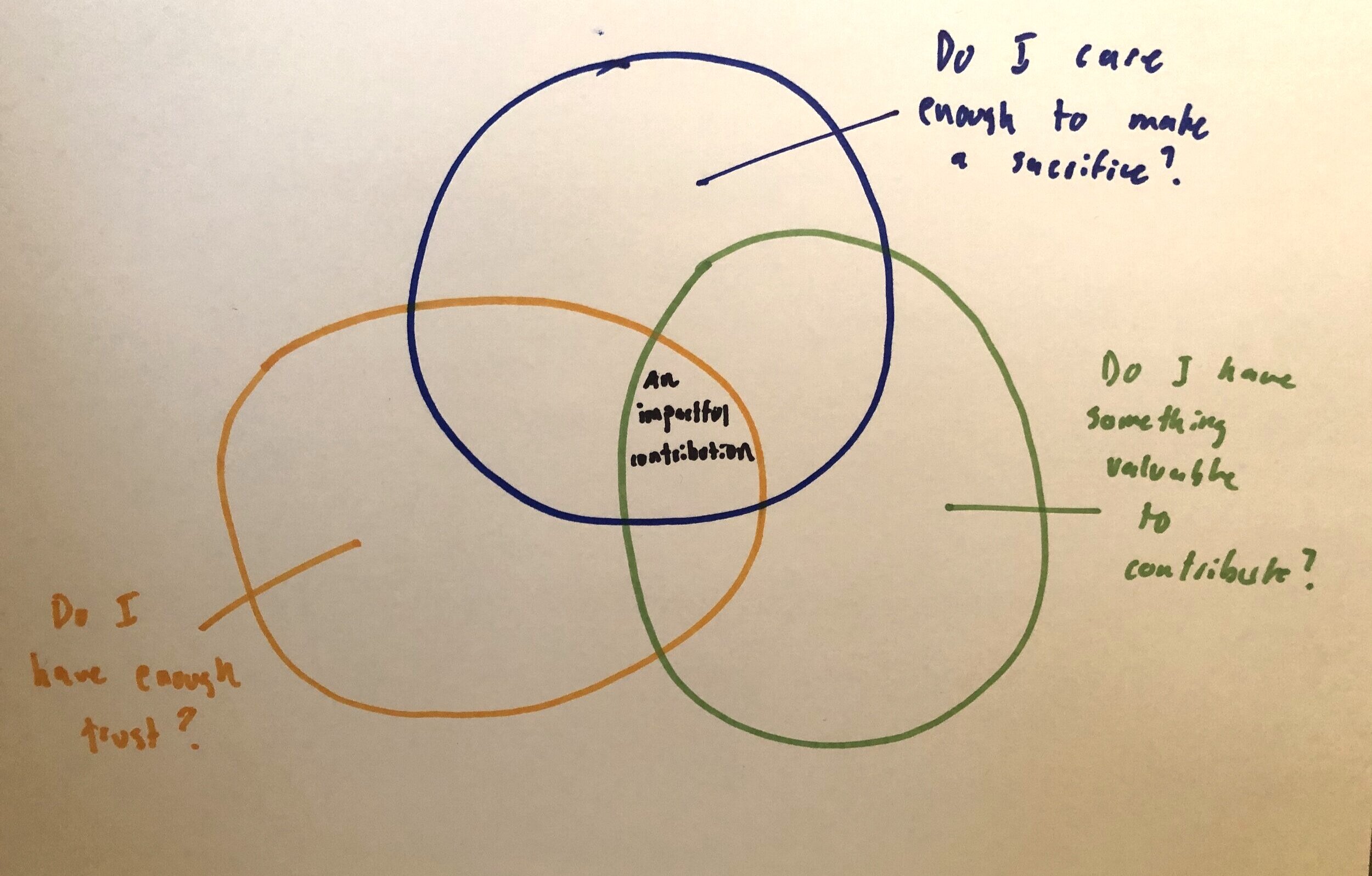

Impactful Contribution

When I’ve already committed to making an impactful contribution, what will I do?

This image of ikigai has been floating around the internet in various forms for a while.

And even though I’m generally skeptical of advice that emphasizes “doing what you love”, I don’t see any reason to criticize the concept the diagram argues for. Those four questions seem sensible enough to me when thinking broadly about the question of “what do I want to do with my life?”

Lately though, in the aftermath of George Floyd’s murder, as protests continue throughout our country, I’ve heard a lot of people ask - “what can I do?”

In this case, the question of “what can I do?” is not a decision where the framework of ikigai easily applies. When it comes to racial equity, if we’re asking the question of what can I do, we’re already committed to issue area and we aren’t expecting to be paid for it.

And this question is common. I have often asked myself, something like what do I want to do to contribute to others when I’m not at work? Nobody has unlimited leisure time, but most of us have some amount of time we want to use to serve others, after we complete our work and home responsibilities. We’re already committed to doing something for others, we just don’t know what to do.

So the question becomes: when I’ve already committed to making an impactful contribution, what will I do?

Here’s how i’ve been thinking about approaching that question lately:

There are three key questions to answer and find the intersection of:

Do I have enough trust to make an impactful contribution?

if so, where?

If not, how can I build it?

Do I have something valuable to contribute?

If so, what is it?

If not, what can I get better at that is helpful to others?

I I don’t know what’s helpful, how do I listen and learn?

Do I care enough (about anyone else) to make a sacrifice?

If so, who is it that I care so deeply about serving?

If not, how do I learn to love others enough to serve them?

Our decision calculus changes when we not trying to determine what to based on whether it will make us feel good. When we’re looking to serve others, it’s not as important to find something we are passionate about doing or finding something which helps us seem important and generous to our peers. What becomes most important is putting ourselves in a position to make an impactful contribution.

Because when we’ve already committed to making an impactful contribution, making that contribution is it’s own reward. We don’t depend as much on recognition to stay motivated. As long as we’re treated with respect, we’re probably just grateful for the opportunity to serve.

Racism, Reform, and the Second Commandment

Can we reform our way out of racism?

In these very dark times, I am struggling to make sense of what is happening in the aftermath of George Floyd’s unfathomably cruel murder by a Minneapolis Police Officer. For a lot of reasons.

We live in a predominately black city. I have worked as a Manger in our Police Department for the better part of the last five years, so I’ve seen law enforcement from the inside. I am, technically speaking, a person of color with mixed-race children. We live in a mixed-race neighborhood.

And of course, there’s the 400+ years of institutionalized racism in the United States that I have begun to understand (at least a little) by reading about it and hearing first-hand accounts from friends who have felt the harms of it personally.

And as I’ve stewed with this, I keep asking myself - what are we hoping happens here? What do we want our communities to be like on the other end of this?

Because something is palpably different this time. George Floyd’s murder feels like it will be the injustice that (finally) sparks a transformation.

What I keep coming back to in contemplation, reflection, and prayer is the second greatest commandment - “Thou shalt love thy neighbor as thy self.”

What I hope for is to live in a place where I can have good neighbors and be a good neighbor. The second greatest commandment is the most elegant representation of what I hope for in communities that I have ever found.

I interpret this commandment as a call to love. We must give others love and respect, even our adversaries. If loving our neighbor requires us to do the deep work of growing out of the fear, disrespect, and hate in our hearts then we must do it. Rather, we are commanded by God to do it.

But in the world we live in today, we can avoid the deep work of personal transformation if we choose to. If we don’t love our neighbors, we can just move somewhere with neighbors we already like. More insidiously, we can also put up barriers so that the people we fear, disrespect, or hate, can’t live in our neighborhood even if they wanted to.

This seems exactly to be what institutionalized racism was and is intended to do. I don’t have to learn to love someone if I keep them out of my neighborhood through, redlining, allowing crummy schools elsewhere, practicing hiring discrimination, racial covenants, brutal policing, and on and on.

If we choose neighbors we already love as ourselves, we’re off the hook for removing the hate from our hearts and replacing it with love for them.

In this, I am complicit. Part of why we live in a city is because I didn’t want to raise mixed-race children in a white, affluent suburb. I didn’t want to deal with it, straight up.

I say this even though I acknowledge that places like where I grew up are probably much more welcoming than they were 15 years ago. Similarly, there are times that I’ve chosen to ignore, block, and unfollow people who I fear, disrespect, or disagree with. I have been an accomplice creating my own bubble to live in.

Adhereing to the idea presented in the second greatest commandment is really quite hard.

The problem is, I and any others who want to live in a truly cohesive, peaceful community probably don’t have a choice but to do the deep work that the second greatest commandment asks of us.

My intuition is that even if we dismantled institutionalized racism completely, that wouldn’t necessarily lead to love thy neighbor communities. They’d be more fair and just, perhaps, but maybe not loving.

And, I’m not even convinced we can completely dismantle racist institutions without more and more people individually choosing to do the deep work of replacing the fear, disrespect, and hate in their hearts with love.

Which leaves me in such a quandary - I truly do believe there are pervasively racist institutions in our society, still. And those institutions need to be reformed - specifically to alleviate the particularly brutal circumstances Black Americans have to live with.

But at the same time, I know I am a hypocrite by saying all this because I too have to do the deep work of personal transformation.

I did the Hate Vaccine exercise last week and realized how fearful and disrespectful I can be toward people from rural and suburban communities because of my race, job, and where I went to college. When I really took a moment to reflect, what I saw in myself was uglier than I thought it would be.

In community policing circles a common adage is that “we can’t arrest our way out of [high crime rates].” I have been wondering if something similar could be said for where we are today - can we reform our way out of racism?

Maybe we can. I honestly don’t have the data to share any firm conclusion. But my lived experience says no: the only way out of this - if we want to live in a love thy neighbor society - is a mix of transforming institutions and transforming all our own hearts.

Thank you to my friend Nick for pointing out the difference between the second commandment and second greatest commandment. It is updated now..