2023: The Year of ‘Not Helpless’

2023 taught me a powerful lesson: facing fears and owning up to my choices proves that, really, we're never helpless.

My biggest regret this year was not attending a memorial service for someone I knew who died unexpectedly.

Despite our distant connection, my grief was real, but fear held me back. I worried about navigating the unfamiliar customs of their faith and feared saying the wrong thing to their family, whom I had never met before. Additionally, I was concerned about how others would perceive my attendance, given our weak ties.

Upon reflection, none of these fears justify my absence, and this regret has been a poignant lesson for me. It seems so obvious now, but I actually have some control over how I react to fear. Nothing but myself was stopping me from making a different choice.

I am glad that even though I feel regret, I have learned something from it: My ignorance is my responsibility and under my control. My irrational fears are my responsibility and under my control. My boundaries and response to social anxiety is my responsibility and under my control. These are all hard, to be sure, but I am not helpless.

—

I’ve now proven to myself that I can do better. This is my greatest accomplishment of the year.

On vacation, where work stress dissolves into the Gulf of Mexico's salt, I find myself more patient with my sons. In the last two months, gratitude journaling helped me realize that I was unfairly expecting my sons to manage my frustrations. This insight has made me a better listener, helping me see them as they need to be seen - closer to how God sees them.

On vacation, when the stress of work dissolves into the Gulf of Mexico’s salt, I am more patient with my sons. In the last 2 months of the year, when some gratitude journaling I did finally made it click that I’m expecting my sons to help me manage my own frustrations, I am better. I am a better listener and I finally see them in the way they need me to - closer to how God sees them.

Now, I know, I can do better - I just have to do it when the world around me feels chaotic and when we’re out of our little paradise and back into our beautiful, but very real, life. This will be extremely difficult, but I know I can do it, because I’ve already done it.

Once I am better - as a listener, as a father, and as a husband when Robyn and I work through this together - I start to talk to them different. I’m curious. I’m asking questions. I’m taking pauses. I’m no longer trying to control and react, I am the powerful wave of the rising tide that is firm but gentle, enveloping them and their sandy toes until they are anchored again.

I change how I talk. Instead of saying - “stop it, now!” I start to say, with a full, palpable, sense of love and confidence in them - “you are not helpless.”

—

Over the years, Robyn and I have taken exactly one walk on the beach together during our Christmas vacation.

We saunter away for 30 minutes at nap time, letting the masks we so reluctantly maintain as parents and professionals fully drop. It's just us, speaking to no one except three young girls who earnestly and eagerly approach us, asking, “Excuse us, but would you like a beautiful sea shell?“

Some years, one of us is weeping as our grief and frustration finally is allowed to boil over. This year though, we are incisive and contemplative. I am honestly curious. We struggled so much this year, how is it that we aren’t more frustrated with each other?

By the end of our walk and our conversation, I see her differently. She is more beautiful, but that’s how I feel everyday. Today, I also feel the depth of her soul and resolve more strongly. Her gravity pulls me in closer.

We have fought hard to get here. All the hard conversations we’ve had and all the conflict resolution techniques we’ve studied and applied have made a big difference. Yes, we have put in the work.

But at the root of it, is something much deeper and strategic. We have seeds of resilience that we have planted consistently with every season of our marriage that passes. We plant and reap, over and over, not a fruit but a mindset. We have vowed to be in union. We are dialed into a single vision that is bigger than both of us. We are committed to make it it there and we have jettisoned our escape pods, figuratively speaking, we have left ourselves no choice but to figure it out.

And with every crisis, we feel more and more that we can figure it out. With each year that passes, the difficulty of our problems increases, but so does our capacity to manage them. More than ever, as the clock strikes the bottom of the hour and we end our saunter, I remember - we are not helpless.

This year was hard. But the silver lining was that I finally internalized something so simple, but so important.

When the going gets tough - whether it’s because of death, our children growing up, or external factors adding stress to our marriage - nobody is coming to save us. We are on our own. But that’s okay, because we are not helpless.

Who should help us measure our lives?

The people who know us intimately and fully.

Who should help me measure my life?

By that I mean, whose eyes should I look through to understand my contribution to the world and the type of person I am? Who should I lean on to confirm whether my life has meaning or is wasted? Who can help me evaluate the parts of myself I can’t see?

To me the answer is simple: the people who know the full extent of who I am. The people who should help us measure our lives are the people that know us intimately. The people who see us in the trenches and up close. The people we cannnot hide our true character from, even if we tried. The people who should help us measure our lives are the people who can see our intent, our thinking, our emotions, our habits, our behaviors, and all the other invisible things we are that are.

Who should help us measure our lives? The people who actually have a 360-degree view of the relevant data about who we are.

By this definition, those are people like our spouses, our families, and our closest friends. Maybe it could also be our colleagues or neighbors who we trust enough to let down our masks and armor. Hopefully we know ourselves in this way, too.

And maybe, it could also be looser ties, who are with us in our most joyous and trying moments - like moments of grief, struggle, sacrifice, or hardship, like doctors, pastors, social workers, or public servants who help us in crises. If we’re lucky, we might also find those people from a team we were on that was trying to accomplish something difficult or of great import - whether that’s our high school theatre group, a soccer team, or a team from our professional life, working on a difficult and meaningful achievement.

What this implies, is that the vast majority of people we’ve ever met aren’t well equipped to help us measure our lives. The people who usually only interact with us based on what they see on LinkedIn or Instagram? Not qualified. Our colleagues? Mostly not qualified, unless we have a generous and transparent relationship with them. Our contemporaries from high school or college? Mostly not qualified, unless they were the people we stayed up all night bonding with, who know us at our best, worst, and most honest.

***

After many years, my inner voice was finally able to bring words to my angst about life and career.

“I am so much more and greater than what my accomplishments suggest. All these people who look at my LinkedIn profile, my job title, and even what I post on facebook don’t know the full story of what I am.”

To be sure, this sentiment causes me and has caused me a deep turmoil and angst. I just get so frustrated because I feel so capable but I don’t have as much to show for it as others. My peers from school (at every level, but especially college and grad school) are objectively a lot more successful and probably more wealthy than me. My peer group has people, too, who have made substantial contributions to the world. Even at work, within my own company, I feel like I have so much untapped potential and ability to create results than the title, rank, and level of respect I currently have.

This, honestly, causes me this deep, churning, in-my-gut kind of angst. I feel sometimes that I’m wasting my talent. On my worst days, I feel like I’m wasting my life.

What I finally realized this week, is that it’s illogical to expect these people to see the full picture of who I am. It’s unreasonable to expect the vast majority of people to help me measure my life, especially because I haven’t let down my guard or had enough time with the vast majority of people for them to see who I am, fully.

There’s no reason for angst about this, because the people that I’m seeking validation from and wanting to help me measure my life, can’t possibly give it.

***

I wish that I could measure my life on my own. Honestly, it would be much simpler if I could see myself clearly enough to make my own adjustments. I want to measure my life, in some way at least, so that I can live a life of integrity and some amount of contribution and meaning. If I evaluate myself, I can make adjustments to be better

The problem is, I can’t adequately self-evaluated because I’m biased. I am a mortal man who has ego. I am not fully enlightened. I need help to see myself as I am. I need the feedback of the people who really know me, deep down, to help me make adjustments so I can be a good guy in a stressed out world. I live enmeshed in a social world, and a community of others - how could I not need help to measure my life if my life impacts the lives of others?

For others to help me measure my life, then, I need to exhibit full-scale honesty: honesty with my self and honesty with others. If I want help measuring my life I have to let people in, and I have to have at least some confidants with who I don’t hid the full gamut of good, bad, and ugly.

This is one of the things I find so compelling about a belief in God: God is someone who there’s no reason to lie to. Because if you believe in God, you believe they know you intimately and fully - there’s no incentive to hide the truth, because God already knows. Similarly, this is why I love journaling - the journal is a safe place to tell the full, completely naked truth. There’s no reason to lie in our journal, if it’s private. If we don’t have people we trust enough to be ourselves, can at least be honest with God and the journal.

What does this all mean? I’m still grappling with this as it’s an entirely new idea for me. What I think this means is two things.

First, I have to be fully honest with myself and with at least some others. And two, I can let go the pressure I feel to be like my more successful peers, because those means of evaluation - social media, my work performance review, or my social standing - is an incomplete picture anyway. I can lean on the people who know me fully to help me measure my life and help me evaluate whether I’m the sort of person I seek to be.

We all can.

From Standing Ovations to Silent Smiles: How My Daydreams Changed

I’ve become more compassionate over the years, but I’m not sure why.

What I visualize has changed over the years, and I can’t figure out why.

When I was younger, I always used to visualize myself being applauded.

In those days, I regularly imagined myself being sworn in as a U.S. Senator, or perhaps being elevated to CEO of a publicly traded company. Sometimes, I wouldn’t even just imagine myself giving a TED talk, I imagined myself watching a video of myself giving a TED talk.

This is objectively vain and narcissistic stuff. These delusions fueled my motivation and ambition. I craved moments of being “awesome” or being “ the guy” and that’s a large part of why I worked hard and tried to achieve success in my education and professional life.

Somewhere along the way that changed.

To be clear, I still have moments where I imagine myself winning something, succeeding, or receiving some sort of promotion. But it’s not only that anymore. Sometimes, now, I visualize others experiencing joy.

Sometimes, for example, I imagine Robyn and I being older and we’re making pizza and chocolate chip cookies with our giggling grandchildren. Or maybe we’re holding hands at church, seeing families of five hugging each other in the pew in front of us, and we feel remember our own joy because we see theirs.

Other times, I imagine our adult sons, joking and laughing with each other, while we’re all having a beer around a campfire. Sometimes, I imagine a time when the world is kinder and more verdant, and I am walking through the park, breathing clean air and passing by birthday parties with loads of youngsters singing and eating cake. They are all strangers and I don’t talk to them, I just notice their glee and I am smiling as I stroll past.

Sometimes, too, I imagine some of the former gang members I met at community meetings dropping their kids off at school or cooking a Friday night dinner, being attentive and loving fathers. Sometimes, I imagine some of the people who buy La-Z-Boy furniture just sitting, and catching their breath in moments of ease.

Again, I’m still self-centered, I’m just not solely that anymore. Now, I imagine others’ joyous moments sometimes too.

The problem is, I don’t know what caused this change to happen.

Was it gratitude journaling or prayer? Was it marriage and kids? Was it losing my father? Was it travel to places, like India, where I witnessed slums with unimaginable poverty? Was it just something that happened because I lived more life? What was it that caused my visualizations to change?

This post doesn’t have a solution, only a question for those of y’all who made it this far. Has this change in perspective happened to you? What do you think did it?

It’s something that I would love to understand enough to recreate on purpose. If I can pinpoint what sparked this shift in me, perhaps we all can learn to intentionally foster a more outwardly compassionate perspective.

Photo by Clay Banks on Unsplash

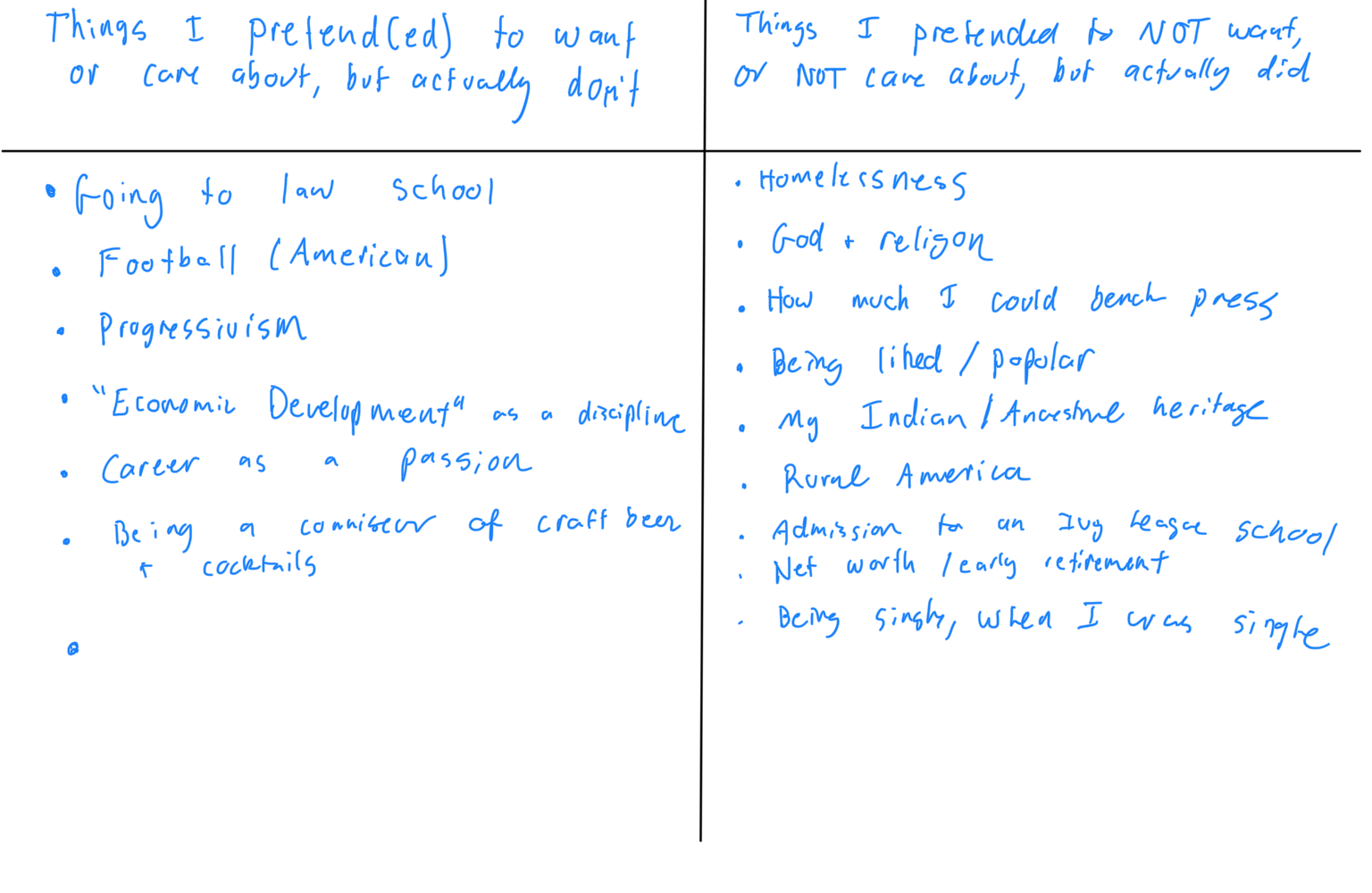

“Dawg, I can’t afford this anymore.”

An exercise in The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck.

These problems matter a lot to me:

How do I be a good guy in a stressful world?

How do I do my part to build a marriage of mutual respect, even though I have selfish tendencies?

How do I show unconditional love and patience as a father, even though my kids need a LOT from me?

How do I bend society to be a more trusting place - even though I’m just one person?

How do I make the organizations and communities I’m a part of places where there’s a virtuous cycle of growth and development - even though I’m just one person?

How do I bend society to have fewer people die by homicide or suicide - even though I’m just one person?

This problem has caused me the most agony in my adult life:

How do I get powerful, influential people to tell me I’m awesome?

Honestly, I was ashamed of being vain and narcissistic enough to need others to tell me I’m awesome. For a long time, I deluded myself into believing that my ambition was wholly for the benefit of my family’s standard of living or the advancement of society.

Honestly, it wasn’t.

I know I shouldn’t be too hard on myself for being vain and narcissistic - I am human. But damn, over the course of my life, this problem has been so expensive. I was probably spending 20-30% of my emotion budget worrying about whether powerful people thought I was awesome.

That’s so expensive. That’s so much of my energy and emotion budget stolen away from more important problems. I just can’t afford that.

I’ve been struggling with this for at least a decade. Then, over the course of a few hours, I listened to a book during a long car ride that presented the question properly. Then, a decade’s worth of change happened in an afternoon.

The book I listened to was The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck, and if you burn energy on unaffordable problems, I’d highly recommend it.

We can choose which problems in our life we give a lot of effort to. Once we have an honest catalog of what we’re spending our emotion budget on, it becomes much easier to say, “dawg, I can’t afford this anymore.”

Resistance against easy

The easy path is attractive. But what would that make me? What would that make us?

At my angriest or most exhausted especially, I question whether my effort to do the right thing makes a difference.

And then I wonder if I should be a bit more “flexible” in how I choose to act. Because…

…I could angle for a promotion by courting competing offers that I never intend to take.

…I could get my colleagues to bend to my will by shaming them a little during a team meeting, sending a nasty email, or politicking with their boss.

…I could yell more at my kids or threaten them with no more ice cream.

…I could pawn domestic responsibilities off on my wife or run to my parents to bail me out.

…I could adhere to a rule of “no new friends” and prioritize the relationships in my life based on social status or what that person can do for me.

…I could say “because I said so”, much more.

…I could make all my blog posts click bait or say things I don’t actually believe to get more popular.

…I could find reasons to take more business trips or weekends with buddies to get away.

…I could play with facts to make them more persuasive.

…I could keep my head down if I notice little problems or injustices that others don’t.

…I could stop listening or talk over quieter people so that I can be heard.

…I could just throw away the toys the kids leave all over the floor.

…I could tear down others ideas, with no viable alternatives, to gain supporters.

…I could, literally, sweep dust under the rug.

…I could do these things to make it a little easier.

Lots of people do, right?

And honestly, I for sure still fail my better angels no matter how hard I try. I’m no perfect man, especially when it it comes to that one about yelling at my kids (yikes).

But damn, if I did shit like this on purpose, what would that make me?

“But what would that make me?” is all I need to ask myself when I want to stop trying so hard. That sets me straight when I want to loosen up a little on principles.

I share all this because I’m feeling the weight of the daily grind a little extra today. And I know I’m not the only one who fights the urge to compromise on their principles, even just slightly.

We could. But what would that make us?

Fatherhood and The Birmingham Jail

To break the cycle, I must engage in self-purification that results in direct action.

Bo tells me what’s on his mind and heart, when it’s just him and I remaining at the dinner table. It’s as if he’s waiting for us to be alone and for it to be quet, and then, right then in that instant he drops a dime on me.

“Today at school, Billy kicked me, Papa.”

This time, thank God, I met him where he was instead of trying to fix his problems.I asked if he was okay, which he was. I passed a deep breath, silently, as I remembered that this is the way of the world - there are good kids that still hit and kick, and there are bullies, and that on the schoolyard stuff does happen. This, I begrudgingly admit to myself, is normal - even though it’s not supposed to happen to my kid.

So I started to ask Bo questions, trying my best to keep my anger from surfacing and making him feel guilty for something he could not control.

Bo, has learned how we do things in our family, what we believe. And in our family, we have strong convictions around nonviolence. He was sad, but he told me that he didn’t hit back. He didn’t meet violence with violence. This is my son, I thought.

I told him how strong he was, and how much strength it takes to not meet a kick with a kick; how strong a person has to be to not retaliate. I said he should be proud of himself, and that I was proud too.

But as we continued, I realized just how much like me, unfortunately, he really is. It also takes strength, I added, to draw a boundary. It takes so much strength to say something like, “I want to be friends with you, but if you continue to kick me, I will not.” It takes so much strength to confront a bully, even an unintentional one.

I talked Bo through the idea of boundaries and how to draw them as best I could. It made him visibly nervous - his five year old cheeks admitting nervous laughter as he tried to change the subject with talk of monkeys and tushys. Boundaries are so hard for him. He really is my son, I thought.

Boundaries have always been hard for me. I haven’t been able to draw them, to say no. They still are. For so long, I couldn’t keep my work at work. I haven’t been able to advocate for my own growth in any job to date or to reject an undesirable project which was unfairly assigned. When a dominating person tries to take and take, I may not roll over, but I don’t challenge them either.

My instinct to please others is so instinctual, I hardly ever know I’m doing it. This inability to draw boundaries is my tragic flaw.

One of my core beliefs about fatherhood is on this idea of breaking the cycle. I think there’s one core sin within me, maybe two, that I can avoid passing on. For me this is the one. This inability to draw boundaries and please others is what I want to break from our linage for all future generations. This is the flaw that I want to disappear when I die. Even before our sons arrived, I promised myself, this ends with me.

As I searched for answers and wisdom in the days that followed, my mind went to Dr. King and the ideas of nonviolence articulated by him and his contemporaries, like Gandhi, who were the only heroes outside of my family that I ever truly had.

I remembered this passage, from his 1963 Letter from a Birmingham Jail (emphasis added is my own):

In any nonviolent campaign there are four basic steps: collection of the facts to determine whether injustices exist; negotiation; self purification; and direct action. We have gone through all these steps in Birmingham. There can be no gainsaying the fact that racial injustice engulfs this community. Birmingham is probably the most thoroughly segregated city in the United States. Its ugly record of brutality is widely known. Negroes have experienced grossly unjust treatment in the courts. There have been more unsolved bombings of Negro homes and churches in Birmingham than in any other city in the nation. These are the hard, brutal facts of the case. On the basis of these conditions, Negro leaders sought to negotiate with the city fathers. But the latter consistently refused to engage in good faith negotiation.

Then, last September, came the opportunity to talk with leaders of Birmingham's economic community. In the course of the negotiations, certain promises were made by the merchants--for example, to remove the stores' humiliating racial signs. On the basis of these promises, the Reverend Fred Shuttlesworth and the leaders of the Alabama Christian Movement for Human Rights agreed to a moratorium on all demonstrations. As the weeks and months went by, we realized that we were the victims of a broken promise. A few signs, briefly removed, returned; the others remained. As in so many past experiences, our hopes had been blasted, and the shadow of deep disappointment settled upon us. We had no alternative except to prepare for direct action, whereby we would present our very bodies as a means of laying our case before the conscience of the local and the national community. Mindful of the difficulties involved, we decided to undertake a process of self purification. We began a series of workshops on nonviolence, and we repeatedly asked ourselves: "Are you able to accept blows without retaliating?" "Are you able to endure the ordeal of jail?" We decided to schedule our direct action program for the Easter season, realizing that except for Christmas, this is the main shopping period of the year. Knowing that a strong economic-withdrawal program would be the by product of direct action, we felt that this would be the best time to bring pressure to bear on the merchants for the needed change.

This letter from Dr. King has always resonated with me. I believe deeply in its ideas of nonviolence and am so humbled by the way Dr. King was able to articulate the point of view so personally, simply, and persuasively.

But I had never before connected the ideas in the letter to my conception of fatherhood. The prose was so relateable and resonant with fatherhood, I found it almost damning.

I do not want my sons to bear the weight that I have borne. I want this flaw - the inability to draw boundaries - to end with me. Others, I’m sure, have others crosses that they bear that they do not want to pass on, whether it’s emotional vacancy, substance abuse, or the fear of failure. Everyone’s tragic flaw is surely different.

But what’s true for me is true for all: I need to lead by example. I will pass what I do not wish to my sons, unless I walk the walk. I need to do the self-purification that Dr. King talks about. I must make a deep change within, if I want to see the change in Bo, Myles, and Emmett.

I cannot simply say to Bo that he must draw boundaries, I must also learn to draw boundaries. I cannot simply coach Bo on how to stand his ground, I have to stand my ground. I cannot simply tell Bo that he has to say no, even when he’s intimidated, I must say no to those that intimidate me.

To break the cycle, I must engage in self-purification that results in direct action.

Dr. King’s conception of nonviolence seems to get at what the essence of fatherhood is for me. It’s a process of trying to be better, in hopes that if we are better they might be better. That they might have one less cross to bear, one less flaw to resolve.

The flaw my father sacrificed for me was that of self-expression. He found it so difficult in his life to articulate what he was thinking and feeling. And that’s what he pushed me to do.

He encouraged me to sing, act, and dance. Even though it was expensive and we didn’t have a ton of extra money growing up, he and my mother never said no to the performing arts. He always showed up, every recital and performance.

But more importantly, he worked to be better himself and I saw that, up close. He joined the local Toastmasters club for awhile. He took online courses in Marketing. Towards the end of his life, he even tried to open his heart to me.

What my father did, was the journey all fathers seem to take. When we are young, we are invincible and full of swag. Then, along the way, we realize and then accept that our fathers are not superheroes, but mere mortals. Then, whether voluntarily or by the hand of life’s misfortunes, we realize that we are flawed, too - before we have children if we’re lucky.

And then the rest of our life is the singularly focused story of overcoming that tragic flaw. The sin we must not pass on, for no reason, perhaps, other than that we must, because that’s what father’s do.

And then there’s our final act, if we are lucky enough to see it. Our children are grown, and are on the precipice of having children of their own. And we hope, with all our hearts, that we have conquered some sin, that we’ve overcome that tragic flaw enough to not pass it on.

Then we pray, with what energy we have left, that our children forgive us for what we could not manage to redeem.

Photo Credit: Unsplash @polarmermaid

The linchpin to goodness: listening to love

The power of listening is that it creates bonds of love and ultimately, goodness.

This post is an excerpt from Choosing Goodness - a series of letters to my sons, that is both a memoir and a book of everyday philosophy. To find out more about this project, click here.

—

In my reflection, the linchpin of goodness is courageous action on the hard stuff, and the linchpin of courageous action is love.

Love, my sons, is what everything we’re discussing comes down to, and not in a soft, lofty, squishy, and non-specific way. For the purpose of goodness, love is tangible and tactical. Love is the brass tacks of the whole enterprise.

As I’ve thought about love, and where it comes from, the most important practice I can think of is listening. And I don’t mean just listening with your ears and your intellect. I mean the most comprehensive listening possible - with your heart, and your whole body and spirit.

There’s absolutely no chance in the world of loving someone if you know nothing about them. At it’s root, love is knowing something of another person’s story. And when we hear that story, we find something to love about them. Something about their essence and what makes them unique and special. Something of the grace that God himself has place within them to shine forth. You have to understand the truth, at least a little to start, of who someone is to love them.

There’s no chance of this knowing of someone and finding something about them to love – with that deep unselfish, sacrificial, redemptive love – unless your heart is open to listening. Knowing and loving someone cannot occur without listening.

Photo Credit: Unsplash @christinhumephoto

Listening is what puts us on the journey to love, because once we start to understand the compelling story, gifts, and grace that everyone has, we are drawn to them – just a little bit more than we were. And then we learn more of their grace, and we’re drawn in a little closer. And then a little closer.

Listening is like gravity, drawing us in closer. As we listen, we start to recognize the light in them that’s as important or more important than our own needs. We start to value who they are, and feel a genuine sense of care and concern for their well being. They become “same human beings.” And without even realizing it, there comes to be love there.

Listening, perhaps, is not a sufficient condition to love, but it is the first necessary condition to love.

When it comes to figuring out how to love, therefore, there is no bigger question than how to open up our whole body and heart and listen. The more and better we can listen, the more its gravity draws us in closer to love.

We can start with the basics. There are tips and practices I suggest to help with the mechanical aspects of listening. Before we learn to listen with our whole body and heart, we can try to listen with just our ears.

There are plenty of resources to help you with it, like these articles from NPR, Harvard Business Review, or TED. Some of the basics techniques are things like, “be quiet”, “confirm your understanding with questions”, or “reserve judgement”; a simple Google search will help you find many other tactics you can use to help with the mechanics of listening.

I don’t have much to add to the body of knowledge on the mechanics of listening and active listening. You can read about and practice those skills on your own. What I’ve found, however, is that to really listen in such a way that it leads to a bond of love, it’s a practice requiring more than just the mechanical. Listening that creates gravity between you and someone else takes opening your heart, which is a much different enterprise than what is thought of commonly as “listening.”

Again we turn to the how. How can we open our hearts?

“Our freedom is inextricably linked to goodness”

“I hope you are persuaded that our freedom, from the ever growing reach of rules and institutions, is inextricably linked to goodness. But for that to happen, more and more people have to choose the work to walk the path of goodness, rather than power. And that my sons, starts with us and the choices we make every day of our lives.“

This post is an excerpt from Choosing Goodness - a series of letters to my sons, that is both a memoir and a book of everyday philosophy. To find out more about this project, click here.

—

Why do we need to be good people?

Photo Credit: Unsplash @jvshbk

We have two really difficult problems when we humans live in a community of others rather than in the state of nature. We have the problem of how to ensure that the community doesn't devolve into a state of violence (i.e., we have to create rules and institutions), and, we have the problem of ensuring that the corrupting influence of power doesn't cause the system of government to rot from within.

My whole adult life, until your mom and I found out we were having you, I've been reading, writing, and thinking about institutions and how to create and run them well. Take a look at our bookshelf at home, the majority of what you'll find are books about institutions in one way or another. For most of my life, I've been nutty about making institutions work better and changing the system to make sure they do.

But since I've been reflecting on fatherhood, and starting to write these letters to you, I've grown more and more confused about institutions and their role in society. I suppose I've come to see institutions more for what they are: an intentional concentration of power that is bounded by rules, controls, and systems to ensure, god willing, that it’s wielded benevolently, and without abuse.

As I’ve challenged myself to think about institutions through the lens of power and goodness, I’ve cooled my singular focus on building better institutions. I don’t like the world that I foresee an institutions heavy approach would create, because institutions necessarily manage, regulate, and constrain freedoms.

I don’t want our world to be one where to resolve conflict, prevent violence, and deter corruption we stack rule on top of rule, penalty on top of penalty, oversight board after oversight board, and check after balance all to deal with conflict and the corrupting influence of power. I don't like the idea of a community that is so controlled and I'm not even sure that it's a strategy that would ultimately lead to less conflict, violence, and corruption.

Which makes building character, and moving toward a vision where our community and culture chooses freely to walk the path of goodness so important to me. A culture motivated by goodness deals with conflict, violence, and corruption by preventing it in the first place; character doesn't require changing institutions, it reduces the need for institutions in the first place.

To be sure, building character and a goodness-motivated culture is at least as difficult as reforming institutions. And we will always obviously need better institutions - the size of our society requires it.

But if it were possible to make our world a place that built character and a culture of goodness, I would much rather live in that world than a world on the verge of subduing itself through laws, regulation, and an ever greater requirement to concentrate power in institutions so those laws and regulations can be enforced.

The schism here you must be feeling, as to how your individual choice to choose the work and walk the path of goodness ladders up to the community’s aggregate culture, is not lost on me. It’s hard to see how individual acts affect the broader culture. But they are connected, because our individual actions affect perceptions of normal and vice-versa.

Our decisions and actions are infectious. The actions you take don't necessarily compel others to behave a certain way, but they do have influence because our actions shape what's normal. For example if you lie, others you interact with consistently will think it is more normal to lie than they otherwise would have, had you not lied. And if you lie consistently, it will give others more implicit, social permission to lie than they otherwise would have. Over time, these seemingly little acts will generate a feedback loop which eventually will be powerful enough to shift what constitutes normal behavior around lying and telling the truth.

But conversely, if you tell the truth, and do it consistently, it will give others the implicit, social permission to tell the truth. Your actions, you see, have reverberations beyond your own life. The book How Behavior Spreads, by Damon Centola, explain this complex system dynamic of how behaviors spread from neighborhood to neighborhood. Pick up that book from our bookshelf at home for a rich discussion about this point.

This observation of how our actions affect others and how the culture affects us is especially important to keep in mind because of the time we live in. Social technologies make it easier and faster to influence what’s normal. And I've noticed that the terrible parts of our humanity are the ideas that spread wider and faster. And so our perception of normal gets skewed.

If we - and by that I mean you and me specifically, in addition to “society” - don't choose the work and walk the path of goodness, behaving with goodness will become less normal, and perhaps even become abnormal eventually. And that to me is a scary, scary world. But remember, we have the ability to shape what is normal with our own choices. Why not shape that normal to be goodness instead of the abuse of power?

I'm not much of a gambler, as you three will come to learn as you get older, but I'll make a bet with you. I bet that at some point in your life you will be in some position of power. Whether at work, at school, or volunteering - in some role, whether big or small. In some, if not all, of these positions you will have an opportunity to be corrupt, even if just in a small way. You'll have an opportunity to abuse the power you have to enrich yourself at the expense of others. And you'll have to make a decision to give into this temptation or not.

The key point here is not that you'll be in a position of power at some point in life, or that in that position you'll have a choice between goodness and power. That is all obvious, and something we've been considering together in these letters since the very beginning.

They key point, rather, is that this choice between goodness and power, between character and corruption will have a real effect on other people's lives. In that moment, when the opportunity to abuse power is thrust in front of you, how you choose to act will have real consequences. How you choose will affect what’s normal, even if it’s just in a small way that adds up over time.

If you choose to live in a community with others, the tension between power and goodness will be a constant part of your life, for your whole life. The choice is not imaginary, it’s a real choice, with real stakes that we must make.

Because we came out of the state of nature, and chose to live in communities this tension between power and goodness, between corruption and integrity will always be part of our life. It's a struggle we have inherited from our mothers and fathers before us and their mothers and fathers before them. And because we are mere mortals, and are not perfectly good, we, as a society, formed rules and institutions to help us navigate and manage that tension.

This may always be what mothers and father think as they prepare for their children to be born, but the America you are being born into seems more and more like it is consumed by a lust of power and control, which leads an ever escalating cycle of conflict, rules, the struggle to control those rules, and conflict again.

I always wondered why your Dada wanted to sacrifice everything and move to the United States. And one day he finally told me. Of course, part of what we sought was greater opportunities for prosperity – what he thought of as a better life than the poverty he experienced in his youth and early adulthood. But I’ll never forget what we hold me next.

He saw corruption in India, his motherland, and in America, his adoptive land. And that’s true. All places, I think, have some amount of corruption, albeit in different forms. But what your Dada believed to be difference between corruption in India and America was that in America the corruption didn’t affect “little people” in their everyday lives. Regular people could have a good life without having to succumb to the effects of corruption on a daily basis. In the halls of power, sure, there was corruption. But he respected that in America regular, everyday, people didn’t get squashed by it.

In the decades since I talked with your Dada about his aspirations to emigrate to America, and his view of life here, I’ve come to agree with him. Corruption is a leach. It siphons prosperity through graft and rent seeking. It saps people of their trust in each other and in institutions. It’s a disease, comparable to a cancer, that slowly eats away at a pleasant, peaceful, and prosperous society. The real enemy of any society is not a policy decision or a rival policy – we all have a stake in solving the corruption problem. To make the community a place worth living in, corruption is our common enemy.

The real practical question to me, then, is how. We have a few strategies, as we’ve seen, to address the problem of corruption. To me abundance is an enabler not a solution. Homogenization is a non-starter. That leaves only two viable strategies – building character and building institutions.

My case for “why goodness” and the need to build character into our culture boils down to this: If we choose to live in community with others, the incidence of corruption is inevitable. Accepting corruption is not an option, and neither is homogenization. We can’t depend on abundance to solve our problems, either. That leaves us with the choices to build institutions and build character, and in reality we need to do both.

But building more institutions comes at a hefty price because the more institutions we depend on, the less freedom we will have. Every rule we make constrains our future choices. That leaves goodness as our best option, even though building a society driven by goodness is extremely challenging. If we choose to leave the state of nature and live in community with others, we must also choose the work and walk the path of goodness so that we can do our part to preserve as much of our freedoms as possible.

The world I hope for me and your mother, and the world I hope to pay forward to you, my three sons, is a world that is truly free – like the freedom of heaven the renowned Bengali poet Rabindranath Tagore describes in Gitanjali 35.

Instead of succumbing to a culture struggling for power, I hope you aspire to find peace in goodness and that the world ends up requiring fewer rules and institutions as time goes on, instead of more. I hope you are persuaded that our freedom, from the ever growing reach of rules and institutions, is inextricably linked to goodness. But for that to happen, more and more people have to choose the work to walk the path of goodness, rather than power. And that my sons, starts with us and the choices we make every day of our lives. We must choose.

Listening comes from discomfort

Listening is a skill that builds character. To build the capacity to listen, I need to be comfortable with discomfort.

Listening might be the most important skill there is. It’s like a steroid for building character muscles.

By listening, I can realize that you, no matter who you are have an extraordinary story - and that will get me to love you more.

By listening, I can find something sacred in you, something of intrinsic value. And if I know that, I can be courageous enough to make a sacrifice for you.

By listening, I can understand what you really need. And then, I can serve you and care for you.

By listening, I give you a voice.

By listening, I can understand that the awful things I assumed about you aren’t true. Listening leads to humility and evaporates stereotypes.

If I could just listen more, I’d be a better man.

But to listen, I need to stop thinking about me for just a minute. For just a little while, I’ve gotta put my task list, my hunger, my fear of failure, and my need to be perceived as awesome off to the side. I’ve got to turn off the voice in my head that says, “I can’t deal with you right now, you’re going to have to wait a minute until I take care of ME.”

That suspension of my ego-monologue is so hard because it creates discomfort. When I put off my own needs, my ego and my body hunker down and make me feel discomfort - emotionally and physically. Which is why it’s so hard to stop thinking about myself and create the space to listen to you - by choosing to listen to you, I’m accepting that discomfort is coming.

I think that’s the key to listening - getting used to discomfort. Because if I can get uncomfortable, get through it, and realize that I got through it, the next time I want to listen I will remember that temporary discomfort is okay. The next time I want to listen to you, I can remind my ego-monologue that the listening to you is a temporary discomfort we can get through.

What I need to do, then, is practicing discomfort. Or more accurately, I need to trick myself into being uncomfortable. Because my ego-monologue will not go quietly into discomfort.

I’ve tricked myself into discomfort before.

Tricking myself into discomfort is when I need to go on a 5 mile run when it’s hot and I go two-and-a-half miles in one direction, which leaves me no choice but to run home. It’s when I force myself to raise my hand in class, so I sweat with the anxiety of maybe saying something stupid. It’s in starting the guided mediation video, so I feel obligated to stew in the discomfort of increasing the awareness I have of my own thoughts.

It’s in playing truth or dare or hot seat around a campfire so that I’ll look like a jackass if I don’t answer a deep, vulnerable, question. It’s in the walk down the wobbly diving board or the steps up to the top of the playground slide, with friends behind you, so there’s no way out other than cannonballing into the cold unknown.

If, through practice, I can get comfortable with being uncomfortable, I can convince my ego-monologue that it can deal with the discomfort of quieting down and letting me listen to you. And if I can listen to you, I can be a better man.

So what I really need to do is make the choice to get into uncomfortable situations, get through it, and create the belief that I’m capable of managing discomfort. Discomfort is a resource I need to build my capacity to listen, and, in turn, a resource I need build my own character.

The real slap in the face is that the same is true for our sons. I have to let them be uncomfortable. I can’t put them into situations of genuine harm, but I can’t rob them of the gift of discomfort either. They need me to let them stew in it.

Photo Credit: Unsplash @kaffeebart

We do not have monsters inside us

For sure, every person is capable of terrible things. But we, as men, don’t have to believe the delusion that we were born with a monster inside us. We have to stop believing that. We can build our identity as men around the parts of us that are most good.

The first time I had the delusion, was probably around the time I started high school. I don’t remember what preceded it, I just remember thinking, “there’s something untamed and dark inside me.”

As I’ve aged, I’ve come to realized that I’m not the only man who has felt the grip of something inside them, small to be sure, but something that feels like evil.

For decades now, I’ve believed this about myself as a man: I have this tiny little seed, deep down, in my heart. That seed is a little root of evil and I must not let it grow. I know there is a monster within, and I must not let it out.

I don’t know from whence this deluision came. But it came.

The delusion reawakened when I started to seeing press about a new book, Of Boys and Men by Richard Reeves, which is about the crisis among men we have in America. I haven’t read the book, yet, but here’s some context from Derek Thompson at The Ringer:

American men have a problem. They account for less than 40 percent of new college graduates but roughly 70 percent of drug overdose deaths and more than 80 percent of gun violence deaths. As the left has struggled to offer a positive vision of masculinity, male voters have abandoned the Democratic Party at historically high rates.

Or this from New York Times columnist David Brooks:

More men are leading haphazard and lonely lives. Roughly 15 percent of men say they have no close friends, up from 3 percent in 1990. One in five fathers doesn’t live with his children. In 2014, more young men were living with their parents than with a wife or partner. Apparently even many who are married are not ideal mates. Wives are twice as likely to initiate divorces as husbands.

I come away with the impression that many men are like what Dean Acheson said about Britain after World War II. They have lost an empire but not yet found a role. Many men have an obsolete ideal: Being a man means being the main breadwinner for your family. Then they can’t meet that ideal. Demoralization follows.

For more than a year, before this book was released, I’ve been grappling with some of its core themes. I might not call my own life a crisis, per se, but I struggle with being a man in America today.

I have been wanting to write about “masculinity” or “the American man” for some time, but have struggled to find the right frame and honestly the guts to do it.

A different version of this post could’ve been about how lonely, and isolated I feel and how hard it has been to maintain the ties I have with close, male, friends from high school, college, and my twenties. Or I could’ve written about the pressure of competition in the workplace and the way other protected groups are supported, but I and other males are not, though we also struggle.

I might’ve written about the confusion I feel - I am trying to operate in a fair and equal marriage with Robyn, but we have no blueprints to draw from because society today and what it means to be a man feels so different from the time I came of age. A different version of this post might’ve be political and angry, pushing back against the stigma I feel when I’m gathering with other men - for example, sometimes I feel like getting together in groups of men is something to be ashamed of because it’s assumed that groups of men will devolve into something chauvinistic or destructive and “boys will be boys” and masculinity is “toxic.”

[Let me be clear though: abusive, violent, exploitative, or criminal behavior is absolutely wrong. And the many stories that have been made public about men who behave this way is wrong. And I’d add, men shouldn’t let other men behave that way, toward anyone. I do not imply with any of the struggles I’ve referenced above that any person, man or women, is exempted from the standards of right conduct because they are struggling.]

What I do imply, is that the struggles that are talked about in public discourse about the crisis of men is real to me, personally. My life does not mirror every statistic or datapoint that’s published about it, but directionally I feel that same struggle of masculinity.

As I’ve searched for words to say something honest and relevant about masculinity, what I’ve kept coming back to is that delusion I’ve believed that there is an evil and dark part of me, even if it’s small and buried deep down, that exists because I am a man. The negative ground that all my struggles of masculity come from is the belief that there’s a monster inside me, and that the balance of my life hangs on not letting him out of the cage.

For me at least, this is the battleground where the struggle of my masculinity starts and ends. No policy change is going to solve this for me. No life hack is going to solve this for me. No adulation or expression of anger is going to solve this for me.

If I want to get over my struggle with my masculinity and difficulties I feel about being a man in America today, I have to dispel the belief that there’s a monster inside me. I have to prove that I am not evil inside and that belief is indeed a delusion. The obstacle is the way.

But how? How do I prove to myself that there’s not a monster, that I was born, inside me?

—

Our neighborhood is full of old houses, built mostly in the 1920s. And fundamentally, there are two ways to renovate an old house. You either paper over the problems, or you fix them and take the house all the way down to the foundation and the studs if you have to.

As it turns out, the only way you really make an old house sturdy is to take it down to the studs, and build from there. Papering over the issues in an old house - whether it’s old pipes, wiring, or mold - leads to huge, costly, problems later. The only way is to build a house is from good bones.

With that model in my head, I thought of this reflection, to hopefully prove to myself - once and for all - that I do not have the seeds of evil and darkness, sown into me because I was born a man.

The rest of this post is my self-reflection around three questions. I share it because I feel like I need to try out my own dog food and demonstrate that it can be helpful. But more than that, if you’re a man or someone who cares about a man, I share all this in hopes that if you also believe the delusion that you were born with a monster inside, that you change your mind.

For sure, every person is capable of terrible things. But we, as men, don’t have to believe the delusion that we were born with a monster inside us. We have to stop believing that. We can build our identity as men around the parts of us that are most good.

—

What are the broken, superficial parts of me that I can strip away to get down to the core of the man I am?

I can strip away the resentment I have about being raised with so much pressure to achieve. I can strip away the bizarre relationship I have with human sexuality because as an adolescent the culture around me only modeled two ways of being: reckless promiscuity or abstinence, even from touching. I can strip away the anger I have because as a south Asian man, I am expected to be a doctor, IT professional, and someone who never has opinions, something to say, or the capability to lead from the front. I can strip away the self-loathing I have about being a man - I can be supportive of womens’ rights and opportunities without hating myself. I can strip back all the times I tried to prove myself as a dominant male: choosing to play football in high school, doing bicep curls for vanity’s sake, binge drinking to fit in or avoid hard conversations, trying to get phone numbers at the bar, or talking about my accomplishments as a way of flexing - I do not need to be the stereotypical “alpha male” to be a man. I can strip away my need for perfection and control, without being soft or having low standards.

I can strip away all pressures to prove my strength based on how I express feelings: I do not have to exude strength by being emotional closed, nor do I need to exude strength by going out of my way to express emotion and posture as a modern, emotionally in-touch man - I can be myself and express feelings in a way that’s honest and feels like me. I can strip away the thirst I have for status, my job title and resume is what I do for a living, not my life. I can strip away the self-editing I do about my hobbies and preferences - I can like whatever I like, sports, cooking, writing, gardening, astronomy, the color yellow, the color blue, the color pink - all this stuff is just stuff not “guy stuff” or “girl stuff.” I can strip away the pressure I feel to be a breadwinner, Robyn and I share the responsibility of putting food on the table and keeping the lights on, we make decisions together and can chart our own path.

Once I strip away all the superficial parts of me, and get down to the studs, what’s left? What’s the strong foundation to build my identity, specifically as a man, from?

At my core, I am honest and I do right by people. At my core I am constructively impatient, I am not obsessed over results, but I care about making a better community for myself and others. At my core, I am curious and weird - that’s not good or bad, it’s just evidence that I have a thirst to explore no ideas and things to learn. At my core, I value families - both my own and the idea that families are part of the human experience. At my core, I care about talent - no matter what I achieve extrinsically I am determined to use my gifts and for others to use there, because if the human experience can have less suffering, why the hell wouldn’t we try? At my core, I believe in building power and giving it away and I am capable of walking away from power. At my core, I care most about being a better husband, father, and citizen.

Now that I’ve stripped down to the studs, what mantra am I going to say to replace my old negative thought of, “I was born with a monster inside me that I can’t let out of the cage?”

I was born into a difficult world, but with a good heart. I am capable of choosing the man I will become.

Photo Credit: Unsplash @bdilla810

Showing Up Is The First Choice

If listening is the key to love, relationships, and trust, choosing to show up is the key to listening.

Listening is the key.

We can love, maybe anyone, after we listen to their story. We can understand and solve many challenges if we are curious enough to listen and learn and understand. Relationships of trust and respect are built upon listening, more than anything else, perhaps. Listening to and knowing our own hearts, strengths, and unrelenting desires is a non-negotiable aspect of finding our way.

And from a posture of listening comes the core foundation of inner strength: courage, persistence, and integrity. I really believe this deeply, and as I’ve aged I’ve come to see listening as the under-appreciated linchpin of character and morality.

If listening is the key unlocking greater virtues, the key to listening is showing up. Only after showing up does listening even become possible. I know this without any empirical data.

I know this when I creep into my inbox, and Robert starts to inexplicably lash out at his brother. I know this when the energy in a work meeting changes based on the percentage of people who have their camera on vs. the percentage who are multi-tasking with their camera off. I know this when Robyn mentions that “Myles was asking for ya” at story time when I’m away on a business trip. I know this when I’ve glazed over half a chapter of my nightstand reading because I’m thinking about my to do list.

I know this when I’m rocking Emmett back to sleep, fuming about the slights I’ve perceived from the day, and he doesn’t settle into sleep on my shoulder until I’ve shifted my thinking to his breathing. I know this when I remember what it’s like to go on a date with Robyn and I’m finally hearing her again, not even realizing that I’ve forgotten how to listen.

And though I can wax about it’s importance, showing up is so hard. We can travel so cheaply, to get anywhere but here. We can be any place in the known universe with a smartphone. We can work from anywhere. We can retreat from the present challenge and justify just about anything under the auspices of “I deserve this” or “self-care”. We can disappear into our to do list, because it never ends anyway.

And there, too, is great distraction in struggle. There is hunger. There is disease. There is violence. There is The fear of missing out. There is uncertainty and mean spiritedness. There is the fear of not being enough or a life without meaning. These struggles are a barrier to showing up.

And most insidious of all, we can tell ourselves we can stop showing up if someone we love seems like they’ve stopped first. Tit for tat. it’s only fair. “He did it first” makes it okay, right?

Showing up is a choice. Rather, showing up is many little choices.

It’s the choice to get enough sleep. Or to put the phone away at dinner. It’s the choice to put a boundary on work hours. It’s the choice to meditate and do yoga to build concentration. It’s the choice to eat nutritious food and drink adequate water to prevent the body from distracting the present.

Showing up is the choice to make eye contact, and not scurry into our house to avoid talking with our neighbor. It’s the choice to hear out our proverbial weird uncle or aunt at Thanksgiving dinner. It’s the choice to not weasel out of a commitment when we get better plans. It’s the choice to breathe deeply instead of letting our attention run wild.

In a world of limitless choice, where we can be almost anywhere physically and digitally, showing up is a choice in itself.

I struggle with this. Most of the time, I act on autopilot and don’t actively choose to show up or not. It just happens or it doesn’t.

Like, literally yesterday I had an AirPod in my ear listening to the Michigan game while we had a family afternoon painting pumpkins and playing soccer, in Long Island, with family we flew across the country to see. In retrospect, why did I need to multitask for the sake of a football game? I was on autopilot.

And perhaps choosing whether or not to show up is not the greatest of all choices. That honor belongs to the choice of whether or not to become a better person. But even if it’s not the greatest choice, choosing to show up is our first moral choice. I must remember this, it is a choice. Showing up is a choice. It’s step one.

Before anything, I must stew on this deeply in my bones: will I choose to show up? And I must repeat the echo the answer in my head as a mantra: Yes, I can choose to show up. I can choose to show up. I can choose to show up.

Photo: Unsplash (@a_kehmeir).

How We Should Treat Aliens

Thinking about how to treat aliens, helps us think about how we treat each other.

How should I treat a glass of water? Here are a few gut reactions:

I should not shatter it senselessly on the floor. Effort and resources went into making the glass. Destroying it for no reason would be wasteful.

I should keep it clean and in good working order. That way, there’s no stress because it’s ready for use. There’s no need to inconvenience someone else with even a trivial amount of unnecessary suffering.

I should use it in a way that’s helpful. It would be exploitative, in a way, if I took a perfectly good glass and used it as a weapon. If it’s there, I might as well use it to quench thirst, or do something else positive with it. Even glasses are better used for noble purposes than ignoble ones.

If I’m thirsty, I should drink the water. After all, it’s here and it won’t be here for ever - life is short.

And finally, if someone else is thirsty, I should share what I have. After all, we’re all in this together, trying to survive in a lonely universe.

How should I treat an alien?

The thought experiment of the glass of water is interesting because I don’t know how the glass wants to be treated. I can’t communicate with the glass, so I don’t even know if it has preferences. It is after all, just a glass.

And because the glass doesn’t have any discernible preferences, all my suppositions on how to treat the glass are a reflection of my own intuitions about how other beings should be treated. The question is a revealing one, if one chooses to play along with the thought experiment, because I’m asking a question that’s usually reserved for sentient being about an inanimate object. I can more easily access my true, unbiased, preference because I’m thinking about how to treat a glass of water and not, say, my wife and children.

Helpfully, asking the question revealed some of my deep-seeded moral principles. Each of these intuitions are builds on one of the statements I made above:

Don’t be wasteful - energy, and resources are finite.

Be kind - other beings feel pain so it’s good not to inflict suffering unnecessarily.

Have good intentions - I have the chance to make the world better, using my talents for good purposes. The world can be cruel, so why not make it more tolerable for others.

Uncertainty matters - Sooner is better than later because we don’t know how much time we have left. If you have an opportunity, take it. The opportunity cost of time is high, and the future has a risk of not happening the way we want it to.

Cooperate if you can - we are all in this universe together, nobody can help us but each other. Life is precious, beautiful, and so rare in this universe, so we should try to keep it going even if it requires sacrifices.

Like a glass of water, if we were to come across an alien species, we would not know what their preferences were. But unlike a glass of water, the aliens might actually have preferences - presumably, the aliens wouldn’t be inanimate objects.

And let’s assume for a minute that we out to respect the moral preferences of aliens, though I acknowledge that whether or not to recognize the moral standing of aliens is a different question, which we may not answer affirmatively.

But let’s say we did.

How we should treat aliens (and how they might treat us)

What this thought experiment helps to reveal is that we have meta-constraints that shape our moral intuitions and in turn, affect our moral preferences.

It matters to our morality that resources and energy are finite. It matters to our morality that we feel mental and physical pain. It matters that the world is an imperfect, sometimes brutal, place. It matters that the future is uncertain. It matters that life is fragile and that for the entirety of our history we’ve never found it anywhere else. Our reality is shaped by these constraints and manifest in how we think about moral questions.

So, like many difficult questions I only have a probabilistic answer to the question of how we should treat aliens: I think it depends. If they face the same sorts of constraints we do, maybe we should treat them as we treat humans. If they face the same constraints we do - like finite resources, uncertainty, and the feeling of physical pain - maybe we could also expect them to treat us with a strangely familiar morality, that even feels human.

But what if? What if the aliens’ face no resource constraints? What if their life spans are nearly infinite? What if their predictive modeling of the future is nearly perfect? What if they know of life existing infinitely across the universe? If some of these “facts” we believe to be universal, are only earthly, it’s quite possible that the aliens’ moral framework is, pun intended, quite alien to our own.

Maybe we’ll encounter aliens 10,000 years or more from now, and maybe it’ll be next week. Who knows. I hope if you are a human from the far out future, relative to my existence in the 21st Century, I hope you find this primitive thought experiment helpful as you prepare to make first contact. More than anything, I’m trying to offer an approach to even contemplate the question of alien morality: one tack we can take is to look at the meta-constraints that affect us at the species and planetary level, and then see how the aliens’ constraints compare.

But for all us living now, in the year of our lord, two thousand twenty two, I think there’s still a takeaway. Thinking about how we should treat glasses of water and aliens provides a window into our own sense of right and wrong. Maybe we can use these same discerned principles to better understand other cultures and other periods of history. Do other cultures have different levels of scarcity or uncertainty, for example? Maybe that affects their culture’s moral attitudes, and we can use that insight to get along better.

If we’re lucky, doing this sort of comparative moral analysis will make the people and species we share this planet with feel a little less, well, alien, while we figure out who else is out there in the universe.

This Is Soul Searching

What has given me organizing principles for living is thinking honestly about what I would be contemplating in the waning moments of my own life.

In the waning moments of my life, what do I want to be true? If I do not die suddenly, and unexpectedly like my father and my others did, I know I will be taking stock of my life. What story do I want to be the real, true, story I am able to tell myself about my own life?

I want it to be true that I did not bring death, senselessly, upon myself. Whatever is left of me after death would be ashamed at my negligence if I was texting while driving, or accidentally injured myself because I was drunk. Similarly, if I died needlessly young because of poor nutrition, air & water quality, rest, stress, or apathy toward my own health, my lingering soul would be devastatingly sad. When my time comes, it will be my time, but I don’t want that time to be recklessly early. Our bones may break, but I do not want to break my own.

I want it to be true that I did right by my family, by other people, and by other living creatures. I would be so regretful if I had lived my life neglecting my family, by being untrustworthy to my friends, disrespectful to my neighbors, unkind to strangers, and insulting to life, as it came to my doorstep, in any form. How could I steal the opportunity for a good day from others? How could I take out anger on children, a dog, or other defenseless creatures? How could I pollute the water or air and bring suffering to living creatures 100 years from now? I cannot selectively value life - I’m either in, or I’m out. And I’m either honest, kind, and respectful of life or I’m not. I either did right by others, or I didn’t. Do or do not, there is no try.

I want it to be true that I used my gifts to make an impactful contribution. I think I have realized that it’s less important to do something “big” or “noteworthy”. What is it that I and few others on this earth could contribute? It takes a village to leave the village better than we found it. What’s my niche? What’s my lane? What’s the diversity of contribution I can bring to the table? Papa always told you that you were a capable person, Honor your gifts, Tambe.

I also want to be at peace with death itself. Some people call this being ready to die, or having come to terms with death. I think that means forgiving and asking for forgiveness. I think that means righting my wrong and accepting the wrongs I could not make right. I think that means having lived a life seeking out, learning from, and hopefully understanding something of the the natural beauty of this world and traveling graciously to experience the beauty of human culture. I think that means having my affairs in order medically, legally, and financially. I think that means having done the hard, spiritual work to be prepared for the unknown and undiscovered country. I think that means knowing that I’ve shared the good parts of life with the good people God has brought me to. I want to be ready. Live like there are 10,000 tomorrows, all of which that may never come.

Thinking through this has been a bit of a reckoning. Am I really living to these principles? I’m not 100% sure.

Do I really, truly, not drive distractedly? Is eating fish consistent with my perspective on respecting life in all its forms? Is working in business, or even public service, really the way to contribute my unique gifts? Have I righted the wrongs of my adolescence and been present for my extended, global family? I’m not quite sure about any of these. I think the exercise of reconciling life today with the person we are at death’s doorstep is what is meant by “soul searching.” And that’s what this is, soul searching.

—-

I have dedicated a significant amount of my life to understanding teams, organizations, and how they work. Understanding these sorts of human systems is one of my unique gifts. And one of the enduring truths of my study is that the way for a human to solve problems is to begin with the end in mind.

What this approach absolutely depends on is knowing what the end actually is. What is our endgame? What are we trying to achieve? What result are we trying to create? We must know this to solve a problem, especially in a team of people.

This post was inspired by a few things - a few conversations with a few members of my extended family at dinner this weekend, and finishing the book The Path to Enlightenment by His Holiness, the Dalai Lama - and it’s become a set of organizing principles of how I want to live. These four ideas: avoiding senseless death, doing right by others, contributing my unique gifts, and find peace with death itself, have been loose threads that I have been trying to weave into a narrative since the beginning of my time writing this blog in earnest, almost 15 years ago.

What I have been missing this whole time is that tricky question - what is the end? What we experience about death in our culture is truly limited. The end of life is not a funeral or a eulogy. The end of life is not what is written about us in a book or newspaper. The end of life is not our retirement party from a job or a milestone birthday in our late ages where everyone makes a speech and says nice things about us.

Those moments are not the end, but those moments are usually what we experience, either in movies, television, or our own lives. The end we have in mind when we tacitly plan out our lives is maximizing those moments. But that’s not the actual end.

At the end of life we are really mostly alone, mostly with our own thoughts. I have never seen dying up close, and I think most people don’t. I did not have grandparents who lived in this hemisphere. My father wen’t ahead so surprisingly. My surviving parents (Robyn’s folks and my mother), thank God, are not quite that old just yet. I have never truly seen the true end of life.

I think for most of my life I have been optimizing for the wrong “end”. I have been trying to design my life around having a great retirement party, or a great funeral. And that has made me put a skewed amount of emphasis on what others might think and say about me one day.

What is the better, and more honest approach is to organize life around the true end: death.

It is hard, but has been liberating. Imagining what I want to believe to be true has given me remarkable clarity on how I want to live. And that is such a gift because, thank goodness, I still have time to make adjustments. It’s not too late. And in a way, I truly believe it’s never too late, because we’re not dead yet. Even if death is only days away, or even hours perhaps, it ain’t over ‘till it’s over. We still have time to choose differently.

The Great Choice

The greatest of all choices is choosing whether or not to be a good person.

In the spring of 2012, my life was a mess - even though it didn't appear that way to almost everyone, even me. But a few people did realize I was struggling, and that literally changed the trajectory of my life. It was just a little act, noticing, that mattered. And from noticing, care. Those seemingly small acts were a nudge, I suppose, that put me back on the long path I was walking down, before I was able to drift indefinitely in the direction of a man I didn’t want to become.

Those small acts of noticing and care were acts of gracious love, that probably prevented me from squandering years of my life. Without a nudge, it might have been years before I had realized that I lost myself. Because in the spring of 2012, I was making the worst kind of bad choices – the ones I didn’t even know were bad.

But I’m getting ahead of myself here.

Trying to become a good person is like taking a long walk in the woods. It’s winding. It’s strenuous. It’s not always well marked and there are a lot of diversions. There’s also, as it turns out, not a clear destination. Being a good person is not really a place at which we arrive, and then just declare we’re a good person. It’s just a long walk in the woods that we just keep doing – one foot in front of the other.

It is not something we do because it is fun. A long walk in the woods can be chilly, rainy, uncomfortable – not every day is sunny.

Righteousness is a word that I learned at an oddly young age. I must have been 10 or younger, I think. It was a world I heard lots of Indian Aunty’s and Uncles say during Swadhyaya, which is Sanskrit for “self-study” and what my Sunday school for Indian kids was called that I went to as a boy. And when those Auntys and Uncles would teach us prayers and commandments and the like – righteousness was a word that was often translated.

My father also used that word, righteous. I can hear him, still, with his particular pronunciation of the word talking to me about the rite-chus path. This idea of taking a long walk in the woods, you see boys, is an old idea in our culture. To me, talking about being a good person, going on a long walk in the woods, taking the righteous path – whatever you want to call it – are not just words and metaphors. It’s a dharma – a spiritual duty. It’s a long walk down an often difficult, but righteous, path.

But it is still a choice. Will we take the long walk?

This is a choice to you, like it was to me, my father before me, and his father before he. All of your aunts and uncles, grandparents, had this choice. In our family, this is a choice we have had to make – will we walk the righteous path or not? Will we do the right thing, or not? Will we take the long walk, day after day, or will we not? Will we try to be good people, or will we not?

This is the great choice of our lives. We have to choose.

This passage is from a book I’ve drafted and am currently editing. To learn more and sign up to receive updates / excerpts click here.

“How do I become a good father?”

The question of how to raise good children starts with figuring out how to be a good person myself.

Let me be honest with you.

I don't know whether I'm a good man, whether I will be a good father, or even whether I'll ever have the capacity to know - in the moment, at least - whether I'm either of those things. I, nor anyone, will truly be able to judge whether I was a good father or a good man until decades after I pass on from this earth.

I do know, however, that is what I want and intend to be. I want to be a good father and the father you all need me to be.