Naming our holiness

Holy is an interesting word. Most people kind of know what it means, without knowing what it means. What is holiness? I’ll know it when I see it.

But what about me, what does it mean to be holy? Am I holy? This post is an attempt to put words to holiness without having to depend on just knowing it when we see it.

My friend Nick was recently ordained as a priest in the Greek Orthodox Church, but fortunately for me, he’s been a spiritual guide to mine for a long time. He recently told me a parable he heard:

A man went to see a monk. And he asked the monk, “Brother, I have a problem and I seek your guidance. I am at a crossroads, should I become a doctor or a lawyer? What does God want me to do?”

The monk thought to himself for a quick moment and quickly replied, “God doesn’t care. Become a doctor or a lawyer, to God it doesn’t matter. But whatever you choose, be holy in it. That’s what matters to God. If you become a doctor, be a holy doctor. If you become a lawyer, be a holy lawyer.”

For me, it was providential advice. I have been focused on career in the wrong way recently. Instead of worrying about promotions and new jobs, what I should be worrying about is being holy where I am now.

But of course, that’s not easy. I do not know what it means to be holy. I am, quite frankly, not holy. And, the holy people I have seen, or met, seem like they are not quite of this world. When I think of “holy” I imagine His Holiness the Dalai Lama or Mother Theresa.

I am not holy like that. I am me, in a puddle of my imperfections and selfishness. After talking with Nick, I wondered - for me specifically, what does holy feel like and look like? What is my holiness? What is the holiest version of myself?

I found it helpful to do an exercise like this:

First, I thought of a few examples of when my attitude, mindset, and how I acted was at its peak of goodness. When I felt like my most pure and good. When I felt like something about my presence was transcendent in some way.

For me that’s when I’m dancing, when I’m lost in thought on a new idea, when what I’m writing dissolves out of my fingers like liquid lightning, or when I’ve had sublime, radically honest conversations around a campfire. There’s something about my mindset that’s been other-worldly, for brief moments at least, when doing those things.

And so I picked those moments apart. What was happening in those moments. How did I feel? What was unique about just those times?

How would I describe the way my mind was in those moments? Intense. How would I describe the way my body was in those moments? Graceful. How would I describe the way my heart and spirit were in those moments? Joyous.

Joyous, graceful, intensity (The Ballet Mindset) is my holiness. That is its name.

I am a mortal man. Dealing with the reality that I will indeed die one day, has been one of the major pillars of my writing and reflection over the past 5 years. Which is why I need so dearly to name this holiness.

I am not perfect. I cannot meditate or think my way into holiness. I also cannot just mimic somebody else. Because I am not capable of being perfectly selfless or loving, I cannot just jump straight to absolute holiness. I have to struggle for it. And yet, holiness eludes me.

Which is why I think it’s so important to try to name our holiness. Like, give it something concrete to rest upon using adjectives of this world. Adjectives that regular people can be for at least a few minutes at a time. Something that we can know if we’ve found it.

I am not perfect enough to just be holy, I have to tag it with words. Most of us cannot be saints or prophets. But the rest of us can be specific.

We can put words to the embers of ourselves and our souls, capable of reaching transcendental states. We can give ourselves a few words to remember - joy, grace, intensity for me - so that when we’re in the throes of everyday life, dealing with difficult children or bosses, or stuck in traffic, or dealing with death and illness whatever, we can remember those words to help us remember what our holiness feels like.

If we can name it, we can get back to that holiness with practice. And maybe someday we will be holy enough to really feel worthy of our best moments. Until then, we keep at it, trying to be the holiness we named.

Surplus and Defining “Enough”

Unless I define “enough”, surplus doesn’t exactly exist.

The idea of surplus is simple, you compare what you have to what you need. If you have more than you need, surplus exists. The concept of surplus is often linked to money or material resources, but I think of it in terms of time and energy.

I’ve thought about the question, “What am I doing with my surplus?” before. But I’m realizing that I’ve missed a more fundamental question: “How much do I need? How much is enough?”

To a large degree, how much we need is a choice.

If I wanted to live by myself and grow my own food off the grid for the rest of my life, I could probably retire tomorrow. If I didn’t want to grow in my job, I probably wouldn’t have to work as hard as I do - I could coast a bit and do the minimum to avoid being fired. If I didn’t care about the health of my marriage or raising our children, I probably wouldn’t have to put as much energy in as I do. If I didn’t have such a big ego, I probably would spend less effort trying to gain social standing. You get the picture.

Defining the minimum standard - after which everything else is gravy - is what creates the construct of surplus in the first place. Because if what I “need” only requires I work a job for 25 hours a week, I now have created 15 additional hours of surplus, for example. If it’s unclear what my bar is, it’s hard to know if I’ve cleared it. Until I define that bar, I have no basis for measurement. Defining what “enough” is is half of the surplus equation.

And I want to know if I’ve cleared bar. Because once I have, then I can use that surplus for things I care about - like traveling, leisure, writing, serving, prayer, time with friends and family, gardening, learning something new, exercising, whatever.

I’m realizing my problem is that I haven’t really defined my minimum standard, so I don’t really know if I have enough. And because I don’t know if I have enough, I am stuck in this cycle of grinding and grinding to get more even though I may not want or need to.

This uncertainly leads to waste. If I do have enough, but don’t know it, I might be wasting my time and energy working for something I don’t want or need. If I don’t have enough, but don’t know it, I am probably misdirecting my time and energy on things that aren’t high priorities.

Either way, if I’m not clear on what I need and how much is enough, I’m likely wasting the most precious resources I have - my time and energy.

For so long I’ve blamed the culture for my anxiety around career and keeping up with the Joneses. I figured that it was things like social media and societal pressures that made me engage in this relentless pursuit of more. But maybe it’s really just on me.

Maybe what I could’ve been doing differently all along is get specific about how much is enough. Maybe instead of feeling like I have no choice but to be on this accelerating cultural treadmill, I could really just turn down the speed or get off all together.

These are some of the questions I haven’t asked myself but probably should:

How much money do we really want to have saved and by when?

What is the highest job title I really need to have?

How respected do I really need to be in my community? What “community” is that, even?

How much do I want to learn and grow? In what ways do I really care about being a better person?

What level of health do I really want? What’s just vanity?

What creature comforts and status symbols really matter to me?

At what point do I say, “I’m good” with each domain of my life? What’s the point at which I can choose to put my surplus into pursuits of my own choosing?

Only after defining enough does it make sense to think about the question of “what should I do with my surplus?” Because until I define “enough”, whether or not I have surplus time and energy isn’t clear. And if it’s not clear, I’m probably wasting it. And surplus is a terrible thing to waste.

Kegerators, Enrollment, and Becoming Better

I am committed to helping us - on this journey to be better husbands, fathers, or citizens - all rise together.

There are two general strategies for making the world we live in better: make better systems or make better people.

More on that after the break - first a story about a kegerator.

—

We took a walk during our neighborhood yard sale and stopped to chat with some neighbors we know from a few blocks over.

“Did ya’ll sell anything?”

To which they replied energetically, “yes, we finally sold our kegerator!”

“Who was this person that bought it? Were they fresh out of school or something?”

”No it was actually an older guy, who was landscaping in the neighborhood. He already had one and he’d been looking for a second one for a long time. He bought it and threw it in his trailer.”

Of course, I thought. A pretty good predictor of who might buy a kegerator is someone who already has one. For whatever reason, they’re already enrolled in the journey of having a kegerator. Maybe they brew beer. Maybe they like throwing parties. Maybe they are amateur chemists who have to keep large vats of liquid cold.

Whoever they are, kegerators are already part of the journey they are on. They’re already sold on them.

—

I believe there are two general strategies for making the world we live in better: making better systems or making better people. And by my observation, there are plenty of people trying to make better systems and not that many people trying to make better people. And also by my observation, good, honest, kind, loving, respectful, courageous, persistent people tend to to be better at making systems and cultures better.

And so that brings me to the journey that I am on. I am trying become a better husband, father, and citizen - at home, at work, and in my neighborhood. That’s my life’s work. It’s my jam and my struggle. It’s my hard, long, lifelong slog. That’s why I write this blog. It’s a journal reflecting on this long walk that I’m on to become better.

Why I share this blog is for others - those on a long walk of their own, or those supporting someone trying to become a better husband, father, or citizen. It’s my attempt at being a lighthouse. By sharing what I have learned and connecting with others my hope is that all of us rise together.

I’ve proven to myself that I’m committed to this journey. For the first time in 15 years of blogging, I’ve published consistently. This post is well beyond my 52nd consecutive week of publishing a post. I’m in it for the long haul.

If you’re on this long walk to become better what can I do for us? Is it writing more or going deeper? Is it getting us together on a zoom call so we have support? Is it starting a book club? Is it organizing a conference? Is it creating software to solve a common problem we face?

There is no meetup for people like us. There is no seminal volume for people like us. There is no watering hole for people like us, that I’ve found at least. Right now, we’re isolated, venturing into uncharted territory, wondering who else is out there that’s on this long walk too.

I am eager to hear from you so we can all rise together. You can leave a comment here, find me on social media (linked on this website) or email me at neil.tambe@gmail.com. There are others, and I’m committed to bring us together in a meaningful way over time.

-Neil

Coaxing my best self to show up

This exercise has helped the best version of myself to show up more than he would otherwise. It’s a “dress rehearsal for the day.”

Historically, the time between hitting the snooze button on my alarm and getting out of bed has been the worst part of my day.

One of two things usually happens. One, I might immediately open my phone and start scrolling through facebook, which gets me amped because of the memes and sensational posts. Or, my mind starts to run through my to-do list, and I feel like garbage out of the gate because I’m always behind and that’s the first emotion I’m feeling to start the day.

Either way, I never fall back asleep, which makes me feel even worse because I’ve wasted 9 (or 18 or 27) minutes of my day on top of putting myself into a bad mood. This cycle repeats, every day.

And every day our culture is like Lucy pulling the football out from under me, and I’m Charlie Brown thinking today is different and ending up on my ass before I’ve even put my slippers on.

This past week, I’ve been trying an alternative snooze cycle.

I’m in bed, my eyes are closed, and I’m cycling through my day. But instead of dreadfully asking, “what do I have to do today?” I’m thinking, “what would my day look and feel like today if I were being the best version of myself?”

And I visualize in my head, myself, going through my day at my best. Hour by hour, I’m feeling my attitude and my body. I’m imagining how I am treating others. I’m thinking about how I’m approach the day’s work if I’m at my peak. I’m thinking about times when my day is going to spiral out of control, and I’m feeling in my bones how to bring it back to balance. I’m thinking less about what I have to do, and more about how I’m going to act.

It’s a dress rehearsal for the day. And it takes about 3 minutes.

I remember from dance recitals growing up, what dress rehearsal feels like. It’s different than rehearsals at the studio, because you’re in the space you’ll be performing and you’re actually wearing the clothes and costume as if it’s the real thing. It’s as close to the real thing as it gets without performing in the actual show.

But there’s less pressure because it’s not the recital; you know it’s not the real show. Which makes it a risk-free rep. But dress rehearsals are amazing because they help your body know what the real thing will be like, for the most part. So when the real show happens, you’re as ready as you can be.

I tried “dress rehearsal for the day” visualization once, and I was hooked. I’ve done it every day since. As I went throughout my day, after the first morning of doing this exercise, I felt like I was in a prepared posture instead of a defensive one. When things started going badly during my day, it’s like my mind and body had muscle memory kick in to recognize that something was wrong and self-correct.

The truth is, I have not been at my best for the past few months. I have been getting angrier at my children more quickly. Resentment piles up faster when I perceive an affront of disrespect from my family or at work. I am more overwhelmed by my to-do list. I have been in a state of general malaise more days out of the week, then I was a year ago. And like most mortal men, when tension piles up, it leads to conflict more often than it would otherwise.

And I don’t want more conflict in my life. I don’t want to be that resentful husband. I don’t want to be that angry father. I don’t want to be that self-absorbed neighbor or colleague.

The problem is, life has trade offs. In addition to not wanting to feel so much tension, I don’t want to give up on the priorities I care about that give me this tension in the first place. Nor do I want to to accept this tension and have a short fuse basically all the time.

There’s one way I see out of this trade off, and that’s to be my best self: behaving with a better attitude and a clearer mind throughout the day. Because my best self is better equipped to deal with this tension than my average self is. My best self creates growth and love from tension, my average self gets washed over by it.

But it’s not easy to get him to show up all the time, even though I want him to. Which is not unique to me, I think. I think a lot of us want our best self to show up more often.

This dress rehearsal visualization has helped my best self show up more regularly (at least a little), which is why I wanted to share it with others.

Snapping out of social comparison

I snapped out of the LinkedIn doom loop by thinking about the sacrifices a counterfactual world would’ve required.

When I’m stuck in a rut of feeling like I don’t measure up to others’ accomplishments, the advice of “remember how lucky you are” or “don’t compare yourself to others” or “focus on being the best possible version of you” just doesn’t work for me. It never has.

And in general I suppose those are good pieces of advice. They just don’t help me get out of a cycle of comparing my accomplishments to the people I went to school with or am friends with on LinkedIn.

Most Saturdays, these days at least, we go on a family walk. We live a few blocks away from a neighborhood coffee shop and we go after breakfast. Bo gets a hot chocolate with whipped cream, Robyn gets a coffee with milk, and I treat myself to a mocha - it is the weekend after all. Riley gets a extra long walk with extra time for smells and Myles is content just looking around and feeling the breeze go by as he rides in the stroller’s front seat.

And today, instead of trying to convince myself to stop feeling down about not being as accomplished as my peers, I started to wonder about trade-offs. After all, I made choices - for better or worse - that led to the spot I’m in today. And I wondered, if I had made different choices, what would I have had to sacrifice?

And I quickly realized, if I had made different choices that led to more professional success (which is mostly what drives my feelings of insufficiency, relative to my peers) I would’ve probably had to give up two things: living in Michigan and being a present husband and father. Which are two sacrifices I was absolutely not willing to make.

More or less, this was the thought exercise I went through:

And sure, after doing this exercise there were a few things that I regret and would do differently, like working harder on graduate school apps or sacrificing some of house budget for lawn care (I am irrationally embarrassed about how much crabgrass and brown patches we have on our lawn).

But by and large, thinking about the sacrifices making different choices would’ve required helped me to snap out of the doom loop of social comparison. Trying to ignore the feeling of not measuring up never works. Think about sacrifices and trade offs, was remarkably helpful.

If you also struggle with measuring yourself up to others’ accomplishments, I hope this reframing of the question is helpful to you too.

When I’m feeling used up

How I respond to feeling used up is a choice. It’s a choice. It’s a choice.

As a general rule, I don’t advocate for myself. It’s not that I avoid it or find it uncomfortable, I never really think to do it. The reason why, making a long story short, is that I’m a people-pleaser. I’m motivated more by making someone’s day than I am by a feeling of personal accomplishment.

To be clear, this is a personality flaw. Because I am a people-pleaser, I end up feeling used and used up a lot. Other people ask for my time and energy and my default position is to say yes, which leaves me feeling depleted.

This is a choice, with trade-offs.

How I respond when I feel used up is also a choice.

On the one hand, I could start saying no. I could protect my time and energy by setting boundaries.

On the other hand, I could insist upon reciprocity. Doing so would make day-to-day life more of a give-and-take rather than a mostly-give and sometimes take.

And seemingly paradoxically, I could give more. By digging deep and giving more, I could practice and get better at expanding the boundaries of my very little heart, and learn to give without receiving just a little more.

In reality, I should probably do some amount of all these things. Honestly though, I hope I don’t have to set boundaries or insist upon reciprocity. I hope instead that I can dig deep within and give more when I feel used up. I hope I’m dutiful enough to give to others, even if it means bearing more weight and sacrificing status or personal accomplishment.

I don’t know if the sinews of ethics and purpose holding me together can sustain that. I am definitely a mortal man, and not a saint. But still, I hope that I can dig deep and give more. It seems to be the choice most likely to create the world I hope to live in and leave behind.

But the revelation here is that it is indeed a choice. I feel so much pressure from our culture that the way to handle feeling used up are things like, “say no” or “self-care” or “manage your career” or “give and take” or “know your worth”.

And all that probably has a time and a place for mortal men like me. But that’s not the only choice. This choice is what I’ve found comforting.

Another way to handle feeling used is to live by wisdom like, “service is the rent we pay” or “nothing in the world takes the place of persistence”or “no man is a failure who has friends” or “be honest and kind” or “the fruits of your actions are not for your enjoyment”.

How I respond to feeling used up is a choice.

The pizza stone, snowblower, and being that kind of man

I want to be humble and generous enough to give without receiving.

Two gifts I’ve been using a lot lately are a snowblower and a (2nd) pizza stone. Both were Christmas gifts from our parents in recent years.

The extra pizza stone has doubled our oven’s throughput for making pizza. Which is convenient for us a nuclear family, but it isn’t essential on a weekly basis. Where it makes a big difference is when we’re hosting - say close friends or family. Having that 2nd stone gives us the capability to throw a pizza party.

Similarly, the snowblower is convenient - especially on days of large snowfall - but not essential. I can muddle through with just a shovel if I really need to. Where the snowblower makes a huge difference is for our block.

Our next-door neighbors and we have an unwritten code: whoever gets to the shoveling first takes care of the others’ sidewalk. This makes it easier for whoever comes out second, and it clears more of the sidewalk, earlier in the day, for people walking down the block. Having the snowblower makes it much more possible for me to honor that neighborly code.

With the snowblower, I can basically guarantee I’ll be able to remove snow from our house, as well as for each of our next-door neighbors in about 30 minutes. Without the snowblower, it might take me closer to two hours on a day of heavy snowfall to manage that same task.

Receiving the stone and snowblower wasn’t a particularly flashy ordeal. Both were extremely generous and practical gifts, but it wasn’t particularly exciting to receive something so mundane, in the moment of unwrapping the present on Christmas day.

But these sorts of gifts, I’ve realized, are much more than practical. I’ve come to think of them as exponential because they give us the ability to give to others. In this example, the 2nd stone and snowblower has made the amount of times we’ll end up throwing pizza parties or helping out our neighbors over our lifetime exponentially greater.

I’ve thought recently, how humble one must have to be to give an exponential gift. When someone says “thanks for the pizza, it was great” I don’t, after all, make it a point to say something like, “You’re welcome, it would probably wouldn’t have happened if our parents hadn’t got us a 2nd pizza stone for Christmas 3 years ago.”

Or talking to our neighbors across the fence, I would never in a 100 years say something like, “No problem, I was happy to get your snow while I was out. The credit really goes to our parents who got us this snowblower. It would have been much harder to help you if not for their gift.”

And it’s not like I frequently say to our parents, “oh thanks for those gifts, it’s really helped me to be a better friend and neighbor.” Maybe I should, but that’s not really the sort of exchange I’d probably naturally have in real life.

Nobody knows the impact these gifts from our parents have had. Our parent’s probably don’t even realize it.

Essentially, when you give an exponential gift like a 2nd pizza stone or a snowblower, you can’t expect to get credit for it. This is much different than say a more novel gift that other people notice, like a consumer electronic or a very nice piece of new clothing.

Take a sweater I got this Christmas, for example. People noticed and said things like, “that’s a nice sweater, is it new?” And I could reply with something like, “oh yeah, I’ve loved it - it was a great Christmas gift from our parents.”

That sort of affirmation doesn’t happen with exponential gifts. Which is why I think giving an exponential gift takes tremendous generosity and humility, because the gift-giver isn’t recognized for it, nor might they even know how impactful their gift was.

And as I started contemplating this, I began to wonder - am I humble an generous enough to give gifts that nobody will ever know I was responsible for? And let’s put aside Christmas and birthdays and get to the big stuff.

What about in my job? Am I unconsciously holding back on making a contribution that I know won’t help me land a promotion? Am I working hard, just so I can get a pat on the back?

Do I volunteer in my community because I relish the credit and respect it provides, or because it’s just the right thing to do? Are there things I do, only because of how someone else might see it on instagram? Am I humble and generous, or am I just a peacock and a brat who gives only to get back reciprocally?

I don’t know how to know this, not yet at least. I think this problem - of knowing whether our own actions are done for their own righteous sake or because of the rewards we expect for them - is one of the essential, practical, moral struggles that we all face.

But I feel strongly that it’s important to try understanding this, and acting differently - more humbly and generously - if we can. Because exponential gifts are transformational in real people’s lives, and they transform the culture we live in for the better. I want to be humble and generous enough to give an exponential gift that I never expect to get any credit or recognition for.

I want to be that kind of man.

The Myth of Hard Work

What I was told would lead to success, led to fragility. Hard things, as it turns out, lead to courage and inner-strength.

My eldest sister, in her infinite wisdom, pointed out the subtle difference between hard WORK and HARD work, while we were WhatsApp video-ing across continents.

We were discussing a book we both happened to have read recently, Viktor Frankl’s Man’s Search for Meaning.

Which, if you haven’t read it, I think you should. It’s an essential work for us in this century, helping us to understand what it means to be human, the extremities of human experience, and the boundlessness of our inner strength.

“Why is it that in those extreme circumstances [of a Nazi death camp] some people could have such a response of strength and courage, while others did not?”, I asked her.

“Hard work,” she replied.

And so I pressed her. What kind of hard work? What kind of work should we do to build up our courage?

“Doesn’t matter,” she replied, again, thoughtfully. She continued and explained the difference to me. It doesn’t matter what the work is, as long as it’s challenging, and a struggle. To build our inner-strength and courage all that matters is that we do work that is hard.

If you’re like me - growing up in a well-to-do suburb, with educated parents - there is a myth you’ve probably been told. Everyone seems to be in on it.

If you work hard, you will make it, they tell us. You will be successful. You will have a good life. Perhaps you don’t even need to have grown up in a well-to-do suburb to have heard this myth. It’s pervasive in America.

Earlier in my twenties and thirties I thought this was a myth because hard work doesn’t necessarily lead to success, if you’re one of the people in this country who gets royally screwed because of your luck, the wealth you were born with, or one of many social identities.

What I got wrong, I think, is that there’s a bigger lie at play in the idea that hard work leads to a good life. The bigger lie, I think, is what hard work actually is.

When you’re told this myth, the hard work is presented like this:

Go to school, get good grades and get extra-curricular leadership credentials. That is hard. Get into a famous college, that is hard. Get good grades in an elite major at that famous college, that is hard. Then get a placement at an elite organization - could be an investment bank, could be a fellowship, could be a big tech firm, could even be an elite not-for-profit - that is hard. And do all this “hard” work and go forward and have a good, successful life.

What I realized after talking with my sister is that all that stuff isn’t actually the hard stuff. We perceive it to be “hard” because it’s made so artificially, through scarcity. It’s only hard to get into a famous college or into a plum placement because there are a fixed number of seats. It’s difficult to be sure, and one has to be skilled, but it’s a well trodden path that is hard to fail out of once you’re in it, that happens to have more applicants than seats.

And everybody knows this. Everybody, I think, who plays this game knows that there’s not that much special about them that got them to this point. It’s luck, taking advantage of the opportunities that have been given, and plodding along a well trodden path.

And I think most people, in their heart of hearts, knows that this game isn’t really hard because it’s not actually important. Degrees or lines on a resume don’t make a difference in the world. Getting a degree has no causal link to actually doing something of importance in the world. It’s an exercise to elevate our own status, without having to take any real risks or have any real skin in the game.

And I think this is why I have spent so much of my life having this fragile sense of accomplishment and confidence. I got good grades and was a “student leader” on paper and got into a good college. I did “well” there and got a placement at a prestigious firm where it was almost impossible to fail out. And so on.

Who cares? That didn’t create much value for anyone, save maybe for me. I was going down a well trodden path. I hadn’t actually done anything of any importance. And in my heart of hearts, I knew that. I felt like a fraud, because I was one. I hadn’t really done anything that hard or remarkable. I just played the game, didn’t fumble the ball I was handed, and was slightly luckier than the next person in line.

Of course I wouldn’t feel confident as a result of going down this well trodden path. Everything I had ever done was to build up a resume. That’s not hard.

So what’s hard?

Taking care of other people - whether it’s a child, a parent, a neighbor, or a sibling. It’s burying a loved one. It’s starting a company that actually makes other people’s lives better, even if it’s small. It’s taking that degree from a famous college and pushing from the bowels of a corporation, toward a new direction that actually solves a novel problem that everyone else thinks is ridiculous.

It’s marriage. It’s growing a garden from seeds. It’s baking a loaf of bread from scratch. It’s figuring out how to install a faucet because you don’t have the money to pay a plumber to do it. It’s making a sacrifice for others. It’s pulling a neighborhood kid out of trouble. It’s creating new knowledge and pioneering something nobody else has figured out. It’s telling the truth and being kind, consistently. This is the stuff that’s actually hard.

So yeah, one of the myths of hard work is that it leads to a good life - we know that isn’t fully true. But honestly, the bigger and more pernicious myth about hard work is that we’re lied to about what the truly important, hard work actually is.

The stuff we were told is “hard”, was all artificial and pursuing it left me fragile. It was only after getting chewed up by life in my late twenties, and going from fragile to broken, that I started to actually do the actually hard work of living.

And that’s when I actually started to feel inner-strength.

When I wasn’t trying to chase a promotion, but was actually trying to work on a team that was trying to reduce gun violence, because our neighbors and fellow citizens were literally dying. That’s hard. When I lost my father suddenly and was picking up the pieces of the life I thought I would’ve had, and the father-son friendship we were finally developing. That’s hard. When I fell in love with my soon-to-be wife, we were married, adopted a dog, and had children; being a husband and father, that’s hard. Monitoring my diet and trying to exercise, not because I wanted to look jacked at the bar, but because I’m confronting and trying to delay my own mortality. That’s hard.

And I say all this, at the risk of sounding like a humble-bragging narcissistic, because I still doom-scroll on LinkedIn, all the time.

I swaggle my thumb up and down the screen, seeing all the updates on promotions and new roles and elite grad school admissions. And I feel myself falling back into that hole of fragile pseudo-confidence, forgetting that I’ve learned all those accolades aren’t the hard work of real life. I forget the path of chasing status, money, and power is not the stuff that actually makes a difference in the world or what builds inner-strength and true courage.

I say all, out loud, this because I need help. I need help to not fall into that hole of that myth again. I need all of us in this collective - the collective that wants to live life differently than the myth we’ve been sold - to pull me back to the path of courage, goodness, and the hard and important work of real life.

And finally, I write all this, as a reminder that if you are also in this collective of living differently, we are in this together, and I am here to pull you back, out of the hole of that myth, too.

Paying Struggle Forward

I torture myself when a mission is going badly. Let’s say it’s a difficult project at work that I’m responsible for.

In the night, as I’m trying to fall asleep, I imagine myself in the CEO’s office, getting reprimanded, in front of my whole team. I feel the burn of my colleagues’ fearful, nauseated glances. I think about what I’m going to tell my wife, with a tail-between-legs posture, feeling like I embarrassed our family.

And when torturing myself in this self-imposed thought experiment, the bosses voice echoes enough to rattle my jaw. In my head I’m thinking, how did this happen, what was I thinking, why does this have to happen to me, why does it always have to be so hard?

But this week, in this particular version of my irrational thought experiment, the CEO asks me a question he never has:

“Why shouldn’t I fire you?”

And now, in a moment of clarity, I snap out of this hazy daydream. The answer is so clear to me. The boss shouldn’t fire me, because the next time we’re in this bad situation I won’t get beat. I’ve learned something.

Bad situations - whether it’s tough projects, losing a loved one, a failed relationship, an addiction, trauma, entrepreneurship, writing a book, climbing a mountain, you name it - are like viruses to me. They knock me on my ass. Sometimes, like viruses, bad situations quite literally make me ill.

But just as bad situations are like a virus, learning from our mistakes is like an immune response. Once we get through it, we’ve learned something. We’ve developed a sort of immuno-defense any time this particular bad situation comes up in the future. And I can share those anti-bodies with others.

The imaginary CEO shouldn’t fire me, I think in my head, because I now know a little bit about how to survive this bad situation, and I can tell the others how, too.

But that means I have to put this bad situation under a microscope and study it. I have to learn from it. I have to learn it well enough to teach others and then I have to actually teach others. Which means I have to tell the story of my struggle and failure again and again.

But reframing this into a process of learning from mistakes and teaching others makes the struggle feel meaningful. When I share what I’ve learned, I’m giving someone else a line of defense against this type of bad situation. They may not have to endure the same struggle as I did. And that is gratifying.

This was a mindset shift for me. In the past, when I’ve had bad situations happen, particularly at work, I’d just struggle. And I’d get angry. And I’d pout. And I’d just live with the struggle in a chronic condition sort of way for a long time. And I’d live in fear of the CEO’s office, or whoever the boss happened to be, until I had a new success to share.

I’ve had that utterly destructive thought of, why does life always have to be so hard, so many times, in so many types of bad situations. Like when my father died. Or when I choked on standardized tests. Or when I’ve had my heart broken. Or when I’ve been way over my head at work. Or when I’ve been up with a newborn that won’t sleep, for weeks at a time. Or when we’ve lived through a global pandemic. Or whatever.

But now I think there’s an opportunity to think differently. All these struggles are terrible, yes. But they don’t have to be in vain. They can be teachable moments, for me yes, but more importantly for others. I - and not just me, we - can give others some level of immunity from the deleterious effects of these bad situations that happen to us. But only if we’re wiling to share what we learn, humbly and specifically.

The option of paying our struggles forward to our children, our friends and families, our colleagues, and our neighbors seems much better than just living through them and forgetting about them.

Debrief questions for parents (and coaches)

We can’t “teach” our kids character, but we can debrief it.

I have been struggling for a long time thinking about how to teach our sons “character.” They won’t learn it from a book, nor will sending them to Catholic school magically make that happen.

What dawned on me this week, is that I can debrief with them. And really do that intentionally.

I attended a wonderful summer camp in high school, it was “student council camp.” And there were lots of character building-activities, that I still remember and think about often.

When I become a camp counselor, I had the opportunity to facilitate those character-building activities. And what we always said amongst other counselors is that it’s not the activity that teaches anything, “it’s all about the debrief.”

Debriefing - the process of helping others learn from their own experiences - is a hard-earned skill. It’s not easy. But it’s essentially all about asking the sequence of questions that highlight the salient information which lead to a a novel insight.

During a debrief, the goal isn’t to tell anyone anything, the goal is to nudge them along by bringing relevant facts to the debriefee’s attention which causes them to have an “aha moment”. In those aha moments, so to speak, they learn a lesson on their own. Good debriefers don’t teach, they help others teach themselves.

Cutting to the chase, I started putting a list of questions that could be used to debrief, even with young children. I needed to write them down to debrief myself I suppose.

I share that list here in case it’s useful to those of us that are parents or coaches. I also share it here in hopes that others share their own debrief questions. If you’re uncomfortable leaving a comment, please do contact me if you have a thought to share, I’d be happy to append it anonymously.

Debrief Questions for Parents and Coaches

How do you feel right now?

Are you okay?

Can you tell me exactly what happened?

Then what happened?

What were you thinking right before you did X?

How do you think this made [Name] feel?

What can you do to make this right?

Why didn’t X, Y, or Z happen instead?

What were you trying to do by doing X?

What could you have done instead of X?

Was doing X okay, or not okay? Why?

What else happened because you did X?

Do you have any questions for me?

What are you going to do differently next time?

What happens next, right now?

Reflection Questions: NYE 2020

Some questions in support of your 2020 holiday reflections.

Robyn and I (and our families) relish the last week of the year as a time to reflect on the year past and upcoming.

Here are a few reflection questions, many that we’ve talked about in our household over the past week. I wanted to share them, since this year in particular warrants reflection and prompts can be helpful.

But whether or not you use these prompts, I do think reflection - whether alone, with a friend, a partner, or a notebook - during this time of year is well worth it. I highly recommend taking at least a few quiet, contemplative minutes before you return to your usual routine.

Happy New Year!

Reflections that look backward:

What have you received this year?

What have you given this year?

How have you made life difficult or inconvenient for others this year?

What did you intend for 2020, and what actually happened?

What were your high points and low points? What emotions did you feel at those points?

What do you now know about how the world works, that you didn’t before?

What happiness or sadness are you still holding onto?

In what ways is your relationship different, or stronger?

How has your perception of life in your community changed this year? How has your view of the world changed?

What activities or people did you find a way to hang onto in some form?

What’s an event that you’d want your grandchildren to remember about this year? What lesson would you share with them?

Reflections that look forward:

What about this year would you continue in the future?

What about this year would you never opt to do again?

What do you intend for 2021?

How do you want to make your closest relationships, like your marriage, stronger in 2021?

What outcome that you want to happen is at the top of your list for 2021?

What’s a way that you want to behave differently in 2021?

What’s something you want to spend more time on in 2021? Less time on?

What phase of life are you transitioning into or out of?

What hard thing do you intend to tackle in 2021, even though you may fail?

What are some of the relationships you want to focus on in 2021?

What’s something that seems urgent but is really just a distraction for your most important 2021 priorities? (Pair with this post on anti-priorities).

What am I doing with my surplus?

I am grateful or a lot this Thanksgiving. But what am I doing for others?

My feelings about "privilege" are complicated.

On the one hand, the data is clear that certain factors that we are born into - like race, gender, sexual orientation, zip code, etc. - are predictive of how healthy, wealthy, and at peace we become.

On the other hand, those with "privilege" still have to avoid screwing up the privilege they have to become healthy, wealthy, and at peace. And that's not trivial, either.

On the other hand, privilege is used as leverage to exploit those with less money and power. That exploitation is wrong.

On the other hand, I can't and don't want to live in a perpetual state of guilt, apology, doubt, and shame about any "privilege" I have. I didn't choose to be born into privilege or non-privilege, just like everybody else.

So what do I do with these complicated feelings?

It seems just as wrong to skewer people with privilege as it is to suggest privilege is a conspiracy. And having some sort of atonement about privilege through acknowledgement or "checking" privilege seems okay, I guess. But I honestly don't know the material, sustained effects it has on our culture. It doesn't seem like enough to simply become aware of privilege.

I've been thinking about this idea of "privilege" lately because of Thanksgiving. I feel extremely lucky to have steady work, work that doesn't require leaving my house, and health insurance. I have a family that I love and loves me back. I have friends and neighbors that I love, and love me back. When people have asked me, "what are you grateful for this Thanksgiving?" these are the things I've talked about.

Talking with and listening to my brother-in-law on Thanksgiving, inspired a different path.

It was helpful to replace the world privilege with "surplus". I have a lot of surplus. I was born into a life of surplus. There are other people who were also born into a life of surplus.

Nobody chooses what surplus they were born into.

But everybody chooses what they do with the surplus they have.

What am I doing with my surplus?

Am I trying to get more? Am I trying to shame others because they have more surplus? Am I trying to reallocate surplus after the fact? Am I trying to convince myself that I deserve the surplus I have? Am I using my surplus to enrich my own life and that of my friends and family with ostentatious luxuries? Am I wasting my surplus? Am I trying to acknowledge and atone for my surplus? Am I trying to stockplie it? Am I trying to bequeath it?

Or am I trying to use the surplus I have to enrich the lives of others?

I honestly don't know if this is the best answer on what to do with these complicated feelings about privilege. And maybe there doesn't have to be one "answer" in the first place.

But the best I can come up with is not worrying so much about privilege itself, and who has more of it than me. To me, it makes more sense to worry about whether I am enriching the lives of others.

"To who much is given, much is expected" is an old idea, but it seems like an enduring and worthwhile principle to apply to this befuddling idea of privilege.

Whose shoulders am I standing on?

Thinking of who lifted me up, gives me courage and strength.

I stand on the shoulders of many.

My parents, my wife, my high-school teachers and club advisers, my professional mentors, civil servants that have worked in my community, scholars who have created knowledge I learned, my friends, my grandparents, veterans of war, veterans of peace, artists, kind strangers, and probably many more that I don’t know.

When asking myself, “whose shoulders am I standing on?” it compels me to keep pushing through adversity. Because, how could I insult all those who lifted me up by giving up now?

But it also raises another question in my mind, “who am I putting on my shoulders?”

Both questions are worth asking. Spending five minutes with those questions brought me to a place of peace, gratitude, and service.

I am determined - 2020 will not become a hashtag | Hurricane-proof Purpose

A note about 2020, algorithming ourselves to find our individual higher purpose.

I am determined not to let this year, 2020, become a hashtag. Every time I hear the punchline of a joke or a meme end in something like, “well that’s 2020 for you” I cringe. To me it’s defeat. It’s a resignation that we do not have agency over our own fate, or at least our reaction to our fate. I am determined not to let 2020 become a hashtag, even if it’s just in my own head.

In most instances, this is where I’d insert an “easier said than done”, but I don’t think so. It’s actually very easy to bounce back from a “that’s 2020” mindset. All it takes is focus on a higher purpose.

If a higher purpose for my life is clear, then all I have to do is focus on that purpose. And just consistently think about that north star purpose and work on that. Focusing on that pre-established higher purpose pushes all of 2020’s qualms - both the legitimate trauma this year has brought, and the whining too - out of my mind.

The key is that purpose can’t be petty, shallow, or ego-driven. It has to be deep. It has to stir to the core. A higher purpose is only higher if it can withstand the hurricane times, like the ones we are living in. 2020 is not the hard part, building a hurricane-proof purpose is the hard part.

For me, that purpose falls into two parts - one related to my private life and the other related to my public life. I have been thinking about this for years, I think, and it’s starting to become clear. But my personal purpose is a bit beside the point right now. What really matters is, “how?”

Three friends of mine, Alison, Glenn, and Nydia, were among a handful that sent me some transformative comments to an early draft of a book I’m writing. Their particular comments pushed me on this point: the difficulty in living a purposeful life is not just living it consistently. That is hard, but how do we even figure it out? What’s the mental scaffolding we can lean on?

I have much more thinking and writing to do on this, but where it starts, for me at least, is being really good at noticing things. And luckily our mind, body, emotions, and perhaps even our soul are very sensitive instruments for finding these purpose-fulfilling moments if we calibrate them properly. Just listening to our mind, body, and gets us pretty far. But for that to work, we have to know how to listen and what we’re listening for.

Step one, I think, is calibration. Perhaps a good exercise is thinking of 5 or 10 instances where you had very strong emotions or were deeply immersed in thought. Maybe there are a couple of moments that you think about obsessively, even though they were seemingly small.

And when I think about my 5 or 10, some of them are self-indulgent feelings. They are times when I had a strong emotional reaction because of external affirmations, power, recognition, and ego. Throw those times out of your sample, they are false positives. Those aren’t the moments that lead to a discovery of higher purpose, in my experience. Rather, those are the moments that have taken me in the precisely wrong direction.

And then, remember those remaining moments vividly in your mind. Really feel them. How would you describe those feelings? Let your guard down, and let the deep feelings of peace, joy, or courage flow through your body. Try to amplify the feeling until you feel it in your torso or your limbs. Get to cloud nine. Go higher. Get to the place where you know in your bones that something about this memory is related to a hurricane-proof purpose. This feeling is your filter to exclude the memories and experiences that are false positives.

Step two, I think, is adding data to your dataset. Think of all the times where you feel similar feelings of deep emotional courage, peace, and joy. Think of all the times where there was something that stirred in you nobly. Think of all the times you felt flow or a state of pure play. As you go through your day, take a pause if you feel the beginnings of those feelings.

Organize these moments in your mind, write them down if you have to. Get as many data points as you can, being careful to separate out the moments that are simply ego-boosters and not examples of the deep, purposeful stirrings we’re looking for. Try to filter out the false positives.

I find zen meditation techniques to be helpful practice for getting better at this type of noticing.

Then explore the data and find the patterns. Talk about it, journal about it, do whatever you have to do. Slowly, the right words to describe purpose emerges. And then it changes as you get more data. And as you get more data, your filter gets better too. It’s very bayesian in a way.

This post became something much different than I originally intended. Whoops.

But the point is, I am personally determined not to let 2020 become a hashtag. The best antidote I can think of is focusing on a higher purpose. It’s easy to say go do it, so these reflections are the best advice I have to offer, so far, as to what that higher purpose may be for you.

I don’t know what help I can be, but please let me know if you think there’s something I can do to support you if you’re on this type of journey. It’s kind of like applying an algorithm to ourselves and what we feel.

One less reason, or, People Who Look Like Me (and my sons)

A Jimmy Fallon Clip with Chadwick Boseman changed the way I think about role models.

Yesterday, I came across this clip of Chadwick Boseman on the Tonight Show with Jimmy Fallon. It moved me to tears.

The scene is staged with a room that contains a framed moved poster for Black Panther. Fans are delivering video messages of appreciation to Boseman. What they do not know, is that the actor is behind the curtain watching them speak in real-time. He then surprisingly pops out to say hello, and the exchanges Boseman and his fans were emotional, funny, and for me transcendent.

I finally internalized what it meant to have people of color who look like you, who are pathbreaking.

The appropriate context here (especially if it's you Bo and Myles who are reading this many years after 2020), is that I've never had a well-known Indian-American that I've related to AND been inspired by.

There are plenty of Indian-American politicians, but many are so far outside of the mainstream that I don't relate to them. The others seem like they've anglicized themselves to win votes.

The lndian-American cultural figures, like actors, businesses executives, and television personalities, either have played caricatures of Indians or are in fields (e.g., like Dr. Sanjay Gupta or Dr. Atul Gawande) that are already associated with Indian vocations, or, they're not American-born (e.g., like Satya Nadella).

And more than that, I've never seen any Indian-Americans that have had a gravitas, grace, or poise about them that have made them exceptional (at least in a domain that resonates with me).

When I saw the Fallon clip, I realized that Chadwick Boseman wasn't just a good actor that played the Black Panther, Jackie Robinson, and Thurgood Marshall. He had gravitas. He was exceptionally talented. He had grace. He was so profoundly regal when playing king T'Challa that his playing of the role was pathbreaking, especially when so much of what Black Panther was is unique and pathbreaking on its own. He persisted through serious illness, in private, to make a gigantic cultural impact.

I remember the second Halloween we had in our home in Detroit. It was 2018, after Black Panther had come out earlier that year. There were so many young, black, men who dressed as the Black Panther. They wanted to be like Chadwick Boseman / King T'Challa. And truth be told, I want to be like King T'Challa. Boseman's work inspired me, too.

And I think there are a handful of people who were not just good at their jobs, they are pathbreaking for one reason or another. People like President Obama, or Beyonce, or a in-process example might be AOC. Or JK Rowling, or Dolly Parton, or Oprah. Or FDR, Viktor Frankl, or perhaps even Eminem. These people did not just make exceptional contributions, they have compelling character or inspiring personal stories.

A lot of people talk about how it's important to have role models that look like you. The narrative around that idea is often something like, "if they made it, I can make it." But I'd put a different spin on it: if they made it my [South Asian ancestry, but everyone fills in their own blank] is no longer a reason why I can't make the contribution I want to. And honestly, it's no longer an excuse either. And that’s truly liberating.

And why I mention that reframe is because for me (and I think this is true with a lot of minority groups) I have this soundtrack in my head telling me that I shouldn't try to do hard things, because I'm destined to fail. Because I'm Indian, or because I'm short. Or because I didn't go to Harvard. Or because my parents are immigrants and don't have a rolodex full of connections. People like me don’t do stuff like this. People like me can’t make exceptional contributions and have grace and gravitas.

These are all these stories that I know are dumb to believe. But it's so freaking hard not to listen to those stories. Or not feel like you're an impostor that has to compensate for some deficiency. And by the way, I don't think anyone (even white men) is immune to this phenomenon. Everyone needs path breaking role models that are like them.

I didn't know until recently that Sen. Kamala Harris or Ambassador Nikki Haley were half Indian. And I was even more surprised to find out that both of them (in their own ways) haven't turned away from their South Asian heritage. They don't hide it, at least in my opinion.

And I suppose it remains to be seen whether either of them are truly pathbreaking, but I don't see any reason why they can't.

And I feel so relieved. I had been without role models who look like me for so long, I didn't realize how important it was to me personally, and how much having a role model that looked like me changed my perception of my own self.

But I am more relieved for my sons. If either Sen. Harris or Ambassador Haley becomes a President or Vice President (and serves with distinction), they are both very close role models for my mixed race half-Indian sons. And my sons will grow up their whole lives with a path breaking role model that proves to them that their mixed-race ancestry doesn't have stop them from making a generous contribution to their communities.

It is a wonderful gift for me, as their father, to know that even if there are so many other reasons for them to doubt themselves, with people like Senator Harris and Ambassador Haley, they have one less reason.

Turning my inner-critic into a coach

Reflection changed my relationship with my inner-critic.

My inner-critic and I have a long, quarrelsome history together. He (my inner-critic is male) was a jerk for a really long time.

He started coming around in middle school. He told me that I should be afraid, especially of talking with girls I had pre-teen crushes on. And then he made me feel terrified of failure in high school. He led me astray in college by making me try to fit the cookie-cutter mold of pre-law, even though I didn’t want to.

Then as a young adult, he reminded me how lonely I was, and rubbed my nose in how I didn’t have a graduate degree or a high enough public profile. He made me feel like garbage about how little I was dating and how I needed to be more elite (his opinion, not mine).

Then, on top of all that - as I approached my early thirties, he scared me into thinking I was not good enough at my job or getting promoted fast enough. When I felt like doing something difficult, unorthodox, or unexpected he naysayed me, “naw you shouldn’t do that, that’s not for you to do” he would say. He also told me, so often, to take instead of give, indulge instead of restrain, ignore instead of love.

Over the course of years he has shamed, scared, cajoled, and ridiculed me. Like I said, he was a jerk for a long time.

I write often about reflection because I think it’s really important. Reflection is the engine that drives learning from experience. I’ve been developing a practice of structured reflection for over 15 years now, and I’ve been working on a project to share what I’ve learned. Reflection is what I’m probably best at and most serious about.

What I’ve realized in the past week, is that reflection is more than just the abstract notion of “learning from experience.” In retrospect, reflection has been a process that has improved my relationship with my inner-critic at least ten-fold. Reflection has transformed my inner-critic and made him into a damn good coach.

This is why I’m becoming something of an evangelist for developing a practice of structured reflection, similar to how someone might run, lift weights, do yoga, pray, or meditate. Almost everyone I’ve had a heart-to-heart conversation with alludes to their inner-critic and how terrible theirs is to them, too.

We all have to manage our own critic, and it seems more useful to channel them rather than silence them.

But how?

Structured reflection - over the course of time - was sort of like having a crucial conversation along these lines, with my inner-critic:

Alright buddy, our relationship is not working out. We need to do something different. You can’t harass me anymore. You’re either going to help me get better, or I’m going to replace you with someone who does.

Here’s a piece of paper with what I believe and how I want to be better. This is what you’re going to coach me to do.

I need you to coach me hard. I need you to be honest, specific, and encouraging. Sometimes, I’m going to need you to give me tough love and tell me hard truths. I understand that. But you will not make me feel like shit and shutdown while you do that. I need you to push me to be the highest version of myself. I need you need to be my coach, not my critic.

You will not heckle me right before I take a leap and do something hard, that we’ve agreed is important to do. In turn, I promise to work hard during practice and listen to what you coach me to do. The only way this is going to work is if we have a symbiotic relationship. need you to get better and you need me because you’ll have nothing to do if I shut you out.

Do we have an understanding?

I did not intend for this to happen when I started to get really serious about practicing reflection. But in retrospect, working through a structured set of reflective prompts and practicing them religiously has given my inner-critic no choice but to become my coach.

Thanks to two friends - Alison and Glenn - who connected some really important dots in my head on this subject. They probably don’t even realized they gave me that gift.

Visualizing the Highest Version of Ourselves

A thought experiment, just like an athlete would do to visualize their peak athletic performance.

I feel so many pressures to “be” very specific, culturally-prescribed, things. Be productive. Be smart. Be professional. Be loving and kind. Be pious. Be cool.

And being all these things is so confusing, because being one seems to conflict with another, much of the time.

Lately, I’ve wondering if I could stop trying to be something specific and try to just be the highest version of myself. Paradoxically, maybe trying to be the best of everything would actually be liberating.

And that’s when this thought experiment came to be. Like an athlete visualizing peak performance in their sport, what if I picked a specific environment in my day-to-day life and just visualized being the “highest” version of myself? It could be in a meeting at work. When with my family on vacation. When running. When mowing the lawn. Doesn’t matter - it could be any environment.

In any environment, what if we tried to imagine the highest version of ourselves? Would we be more likely to live up to it? Would the process change us? Would we be more or less frustrated at ourselves?

I didn’t know, so I gave it a try. I don’t think you need to read my reflection (below), unless you want to. I include it only to illustrate what I mean.

What I will say is this, I did this on a whim, just to see what would happen. And I don’t know what will happen in the future.

But after I did this thought experiment (in italics below), I had a tingling feeling in my lower abdomen. Not the queasy stomach feeling, but the kind of tingling you feel when you are about to give someone a gift on their birthday. Or the butterflies you get at the last step before solving an equation in math class. Or when the curtain goes up at the theater.

If you want to, give it a try. Just take the sentence below and replace what’s after the ellipsis with something relevant to you. I hope you get the same warm, tingling feeling if you try it for yourself.

I close my eyes as I type this, and push myself to imagine the highest version of myself in a typical situation…in this case when eating dinner, with my family, on a week night, 12 years from now.

I am at the dinner table. Specifically, our dinner table at home with my wife and kids. It is about 12 years from now - say in 2032. We are eating tacos, the same way we have every other Tuesday for nearly 15 years. It’s early autumn. We all sit quietly and pass our dinner around the table, everyone taking a turn. We are light and easy and comfortable feeling, because we are home. Robyn is laughing with one of the boys about a new joke they heard from a son’s friend on their way home from school - Robyn had pickup duty today. I laugh as I put a dollop of sour cream atop a small mound of avocado. Even though I am assembling a taco, I’m paying close attention to everyone. I look up, giggling at the joke.

I scan the room with my eyes only, this is my opportunity to check how everyone is feeling. If they are laughing as they normally do, all is well. I see our other son crack a smile but he doesn’t laugh. Hmm, how unlike him.

I quickly look down at everyone’s plate. Normal, normal, normal, hmm. Our same son, the one that didn’t laugh didn’t take as many tomatoes as he normally does. How unlike him. I sit up straight and start my meal, keeping him in the corner of my eye softly.

We do our nightly ritual of catching up on the day, and we do our “highs and lows”. My son seems to be his normal self, but his eyes are wandering a little bit. There’s something distracting him. I decide instantaneously that I should try talking to him after dinner. I mentally note that and focus my attention back on the entire family and our meal, so I don’t disengage myself.

As we start to break from the table, I ask, “Son, could you help me store the dog food? It’s a pretty big bag and my wrist still hurts from playing tennis yesterday.”

I probably could store the dog food myself. But my wrist IS still sore and I want to create the space for him to open up.

I ask him as he opens the container, “So bud, what have you been thinking about lately?” As he pours the kibble into the bucket, he starts to talk. He mentions a friend off-hand and how he had to cancel on their weekly study session.

I see my opening, but I opt not to take it. Instead I say, “Hey bud, since you’re already over here would you mind helping me load the dishwasher?” When he agrees, I smile extra wide and say thank you.

We chit chat the whole time. Just as we load our last plate, my son pauses, seeming to collect his thoughts. And then he hesitates. I wait . Then I gently raise my eyebrows to let him know that it’s his turn to speak if he wants to.

He takes my cue. Then he says, “Hey papa, have any of your friends ever avoided you?”

I take a moment, and pour two glasses of water. I motion him over to the now spotless dinner table.

“Yeah bud, sometimes. Let’s relax for a minute and I’ll tell you about it.”

Impactful Contribution

When I’ve already committed to making an impactful contribution, what will I do?

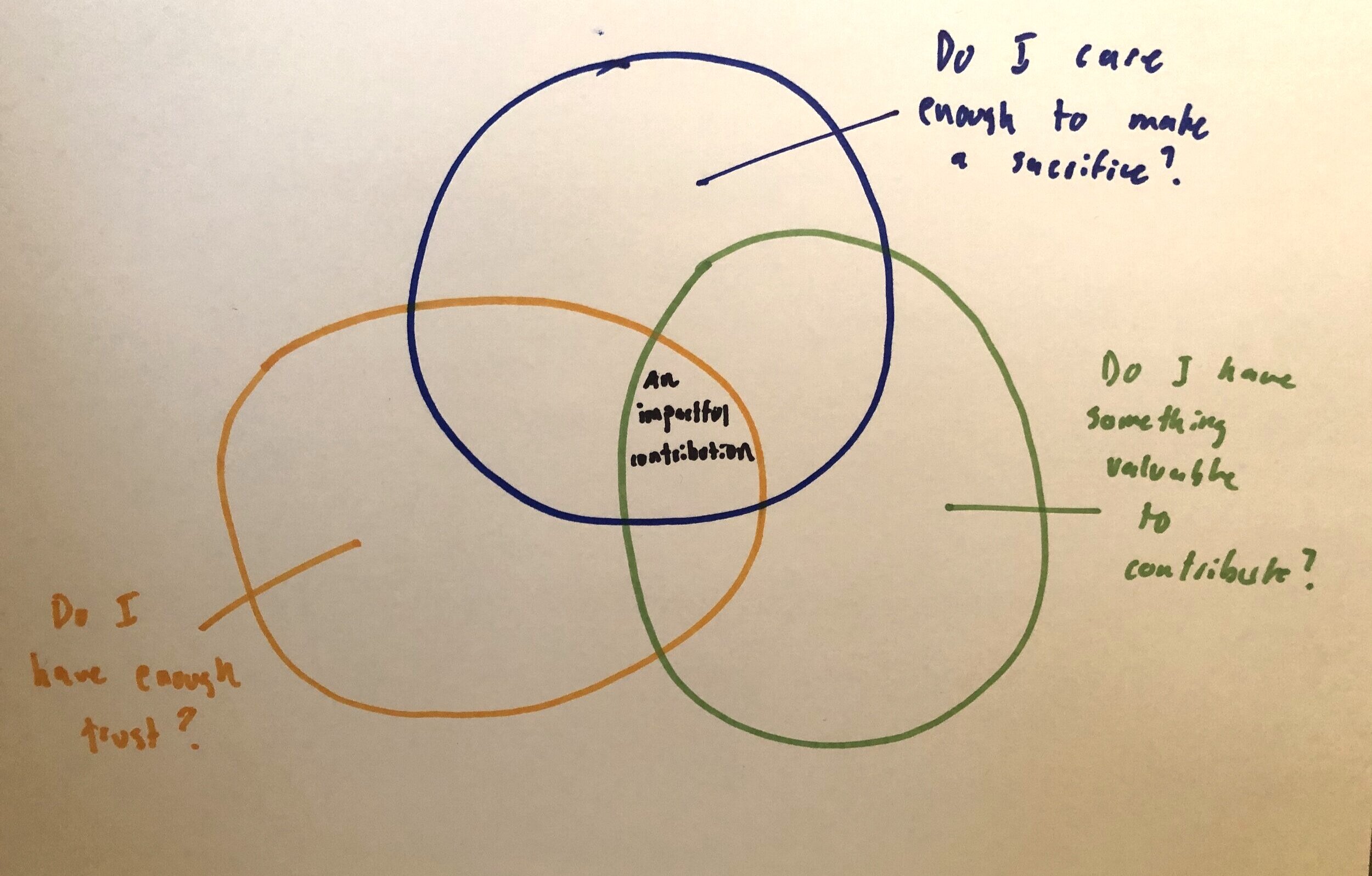

This image of ikigai has been floating around the internet in various forms for a while.

And even though I’m generally skeptical of advice that emphasizes “doing what you love”, I don’t see any reason to criticize the concept the diagram argues for. Those four questions seem sensible enough to me when thinking broadly about the question of “what do I want to do with my life?”

Lately though, in the aftermath of George Floyd’s murder, as protests continue throughout our country, I’ve heard a lot of people ask - “what can I do?”

In this case, the question of “what can I do?” is not a decision where the framework of ikigai easily applies. When it comes to racial equity, if we’re asking the question of what can I do, we’re already committed to issue area and we aren’t expecting to be paid for it.

And this question is common. I have often asked myself, something like what do I want to do to contribute to others when I’m not at work? Nobody has unlimited leisure time, but most of us have some amount of time we want to use to serve others, after we complete our work and home responsibilities. We’re already committed to doing something for others, we just don’t know what to do.

So the question becomes: when I’ve already committed to making an impactful contribution, what will I do?

Here’s how i’ve been thinking about approaching that question lately:

There are three key questions to answer and find the intersection of:

Do I have enough trust to make an impactful contribution?

if so, where?

If not, how can I build it?

Do I have something valuable to contribute?

If so, what is it?

If not, what can I get better at that is helpful to others?

I I don’t know what’s helpful, how do I listen and learn?

Do I care enough (about anyone else) to make a sacrifice?

If so, who is it that I care so deeply about serving?

If not, how do I learn to love others enough to serve them?

Our decision calculus changes when we not trying to determine what to based on whether it will make us feel good. When we’re looking to serve others, it’s not as important to find something we are passionate about doing or finding something which helps us seem important and generous to our peers. What becomes most important is putting ourselves in a position to make an impactful contribution.

Because when we’ve already committed to making an impactful contribution, making that contribution is it’s own reward. We don’t depend as much on recognition to stay motivated. As long as we’re treated with respect, we’re probably just grateful for the opportunity to serve.

The Hate Vaccine - A Reflection Exercise

This exercise is how I am trying to vaccinate myself so I don’t continue to be a carrier of hate, disrespect, and fear.

I subscribe to Michael Jackson’s theory of progress: “if you want to make the world a better place, take a look at yourself and make a change.”

If I want hatred, disrespect, and fear to stop spreading, that means I must not spread it myself.

This exercise is how I am trying to vaccinate myself so I don’t continue to be a carrier of hate, disrespect, and fear. I’m presenting it mostly without comment, but I will say this. When I worked this exercise last night, I realized there’s a lot I can do to be less hateful, disrespectful, and fearful.

INSTRUCTIONS: Start by determining the people / groups that have wronged you or you are expected to exchange hate, disrespect, or fear with. Then fill in the remaining boxes.

I’m working on a project related to practicing reflection, which you can learn more about at the link.

Picking ourselves up is only the first step

Getting up off the mat is not the act that matters, it’s a prerequisite.

Every work day, I begin with a short reflection, starting with this question: “What did yesterday say about my character?”

A few days ago, this is how I answered the question:

“You are getting off the mat. But the important part is not about you getting up, that’s not the heroic act that matters. What matters is what you do for others now that you’ve gotten up.”

It’s uncomfortable how prescient that was a few days ago, because I was furloughed (hopefully temporarily) from my job today. Now, I really get to test whether I can practice what I preach.

When we’re facedown on the mat, our first decision is whether or not we will rise again. But getting up is not enough.

The second decision is what truly reveals our character: what will we do for others one we have gotten up?