Maximizing Organizational Performance: 7 Key Questions

Making organizations better is hard, but it doesn’t have to be complicated.

Leaders are often charged with "making the organization perform better." That's an incredibly difficult mission unless we understand what an organization, especially ours, is and how it works. Only then can we diagnose organizational problems and make improvements.

This is a pretty long, nerdy post, so here's the tl;dr for those in a hurry, and for those who need a little taste to prove the read is worth it.

If you're trying to make an organization perform better, start by asking (just) seven questions. I think you'll make sense of your biggest problems pretty quickly:

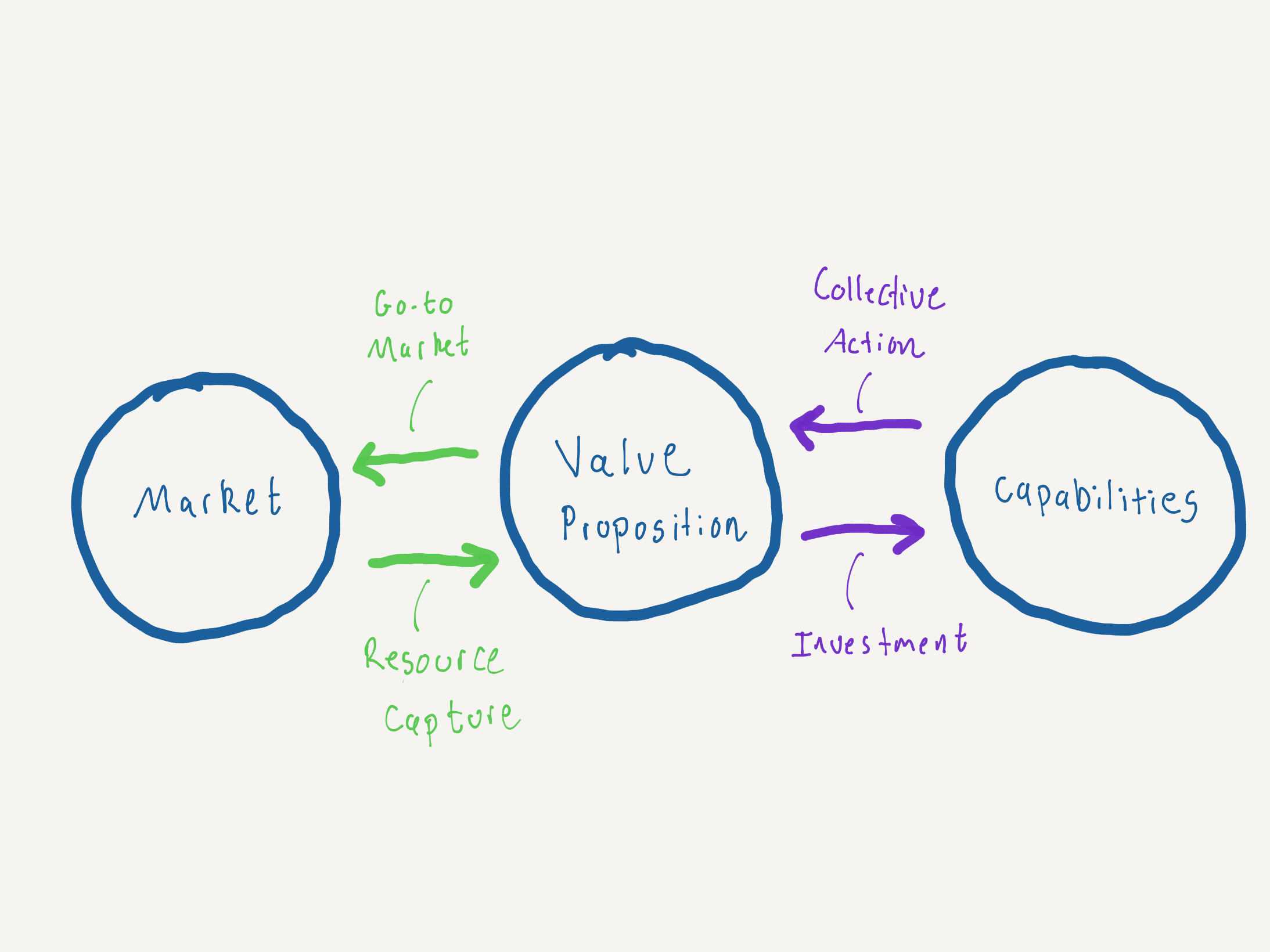

Value Proposition: What do we create that other people are willing to sacrifice something (i.e., pay) for?

Market: Who cares about what we have to offer?

Capabilities: What are the handful of things we really need to be good at to create something of value?

Go-to-Market Systems: How will we engage with our market?

Resource Capture Systems: How does the organization get the resources it needs?

Collective Action Systems: How will we work together to turn our capabilities into something of value?

Investment Systems: How will we develop the capabilities that matter most?

Making organizations better is hard, but it doesn't have to be complicated.

Leaders are often charged to “make the organization perform better”. That’s an incredibly difficult mission unless we understand what an organizations, especially ours, is and how it works. Only then can we diagnose organizational problems and make improvements.

This is a pretty long, nerdy, post so here’s the tl;dr for those in a hurry, and for those that need a little taste to prove the read is worth it.

If you’re trying to make understand and organization and help it perform better, start with asking (just) seven questions. I think you’ll make sense of your biggest problems pretty quickly:

Value Proposition: What do we create that other people are willing to sacrifice something (i.e., pay) for?

Market: Who cares about what we have to offer?

Capabilities: What are the handful of things we really need to be good at to create something of value?

Go-to-Market Systems: How will we engage with our market?

Resource Capture Systems: How does the organization get the resources it needs?

Collective Action Systems: How will we work together to turn our capabilities into something of value?

Investment Systems: How will fwe develop the capabilities that matter most?

Making organizations better is hard, but it doesn’t have to be complicated.

The Seven-Part Model of Organizations

So, what is an organization?

I'd propose that an organization, at its simplest, is only made up of seven components:

Value Proposition

Market

Capabilities

Go-to-Market Systems

Resource Capture Systems

Collective Action Systems

Investment Systems

If we can understand these seven things about an organization, we can understand how it works and consequently make it perform better. There are certainly other models and frameworks for understanding organizations (e.g., McKinsey 7-S, Business Model Canvas, Afuah Business Model Innovation Framework) which serve specific purposes - and I do like those.

This seven-part model of organizations is the best I've been able to produce which maintains simplicity while still having broad explanatory power for any organization, not just businesses. Each component of the model answers an important question that an organization leader should understand.

The seven parts (Detail)

The first three parts of the model are what I think of as the outputs - they're the core foundation of what an organization is: a Value Proposition, a Market, and a set of Capabilities.

Value Proposition: What do we create that other people are willing to sacrifice something (i.e., pay) for?

The Value Proposition is the core of an organization. What do they produce or achieve? What is the good or the service? What makes them unique and different relative to other alternatives? This is the bedrock from which everything else can be understood. Why? Because the Value Prop is where the internal and external view of the organization come together - it's where the rubber meets the road.

It's worth noting that every stakeholder of the organization has to be satisfied by the Value Proposition if they are to engage with the organization: customers, constituents, shareholders, funders, donors, employees, suppliers, communities, etc.

Market: Who cares about what we have to offer?

Understanding the Market is also core to an organization because any organization needs to find product-market fit to survive. This question really has two subcomponents to understand: who the people are and what job they need to be done or need that they have that they're willing to sacrifice for.

It's not just businesses that need to clearly understand their Markets - governments, non-profits, and even families need to understand their Market. Why? Because no organization has unlimited resources, and if the Value Proposition doesn't match the Market the organization is trying to serve, the organization won't be able to convince the Market to part with resources that the organization needs to survive - whether that's sales, time, donations, tax revenues, or in the case of a family, love and attention from family members.

Capabilities: What are the handful of things we really need to be good at to create something of value?

Thus far, we've talked about what business nerd types call "product-market fit," which really takes the view that the way to understand an organization is to look at how it relates to its external environment.

But there's also another school of thought that believes a firm is best understood from the inside out - which is where Capabilities come in.

Capabilities are the stuff that the organization has or is able to do which they need to be able to produce their Value Proposition. These could be things like intellectual property or knowledge, skills, brand equity, technologies, or information.

Of course, not all Capabilities are created equal. When I talk about Capabilities, I'm probably closer to what the legendary CK Prahalad describes as "core competence." Let's assume our organization is a shoe manufacturer. Some of the most important Capabilities probably are things like designing shoes, recruiting brand ambassadors, and manufacturing and shipping cheaply.

The shoe company probably also has to do things like buy pens and pencils - so sure, buying office supplies is a Capability of the firm, but it's not a core Capability to its Value Proposition of producing shoes. When I say "Capabilities," I'm talking about the "core" stuff that's essential for delivering the Value Proposition.

Finally, we can think of how Capabilities interact with the Value Proposition as an analog to product-market fit, let's call it "product-capability fit." Aligning the organization with its external environment is just as important as aligning it to its internal environment.

When all three core outputs - Value Proposition, Market, and Capabilities - are in sync, that's when an organization can really perform and do something quite special.

In addition to the three core outputs, Organizations also have systems to actually do things. These are the last four components of the model. I think of it like the four things that make up an organization's "operating system."

Go-to-Market Systems: How will we engage with our Market?

How an organization "goes to market" is a core part of how an organization operates. Because after all, if the product or service never meets the Market, no value can ever be exchanged. The Market never gets the value it needs, and the organization never gets the resources it needs. A good framework for this is the classic marketing framework called the 4Ps: Price, Product, Place, and Promotion.

But this part of the organization's "operating system" need not be derived from private sector practice. Governments, nonprofits, faith-based organizations, and others all have a system for engaging with their Market; they might just call it something like "service delivery model," "logic model," "engagement model," or something else similar.

The key to remember here is that go-to-market systems are not how parties within the organization work together; it's how the organization engages with its Market.

Resource Capture Systems: How will the organization get the resources it needs?

Just like a plant or an animal, organizations need resources to survive. But instead of things like food, sunlight, water, and oxygen, and carbon dioxide, organizations need things like money, materials, talent, user feedback, information, attention, and more.

So if you're an organizational leader, it's critical to understand what resources the organization needs most, and having a solid plan to get them. Maybe it's a sales process or levying of a tax. Maybe it's donations and fundraising. Maybe for resources like talent, it's employer branding or a culture that makes people want to work for the organization.

This list of examples isn't meant to be comprehensive, of course. The point is that organizations need lots of resources (not just money) and should have a solid plan for securing the most important resources they need.

Collective Action Systems: How will we work together to turn our capabilities into something of value?

Teamwork makes the dream work, right? I'd argue that's even an understatement. The third aspect of the organization's operating system is collective action.

This includes things like operations, organization structure, objective setting, project management approaches, and other common topics that fall into the realm of management, leadership, and "culture."

But I think it's more comprehensive than this - concepts like mission, purpose, and values, decision chartering, strategic communications, to name a few, are of growing importance and fall into the broad realm of collective action, too.

Why? Two reasons: 1) organizations need to move faster and therefore need people to make decisions without asking permission from their manager, and, 2) organizations increasingly have to work with an entire network of partners across many different platforms to produce their Value Proposition. These less-common aspects of an organization's collective action systems help especially with these challenges born of agility.

So all in all, it's essential to understand how an organization takes all its Capabilities and works as a collective to deliver its Value Proposition - and it's much deeper than just what's on an org chart or process map.

Investment Systems: How do we develop the capabilities that matter most?

It's obvious to say this, but the world changes. The Market changes. Expectations of talent change. Lots of things change, all the time. And as a result, our organizations need to adapt themselves to survive - again, just like Darwin's finches.

But what does that really mean? What it means more specifically is that over time the Capabilities an organization needs to deliver its Value Proposition to its Market changes over time. And as we all know, enhanced Capabilities don't grow on trees - it takes work and investment, of time, effort, money, and more.

That's where the final aspect of an organization's operating system comes in - the organization needs systems to figure out what Capabilities they need and then develop them. In a business, this could mean things like "capital allocation," "leadership development," "operations improvement," or "technology deployment."

But the need for Investment Systems applies broadly across the organizational world, too, not just companies.

As parents, for example, my wife and I realized that we needed to invest in our Capabilities to help our son, who was having a hard time with feelings and emotional control. We had never needed this "capability" before - our "market" had changed, and our Value Proposition as parents wasn't cutting it anymore.

So we read a ton of material from Dr. Becky and started working with a child and family-focused therapist. We put in the time and money to enhance our "capabilities" as a family organization - and it worked.

Again, because the world changes, all organizations need systems to invest in themselves to improve their capabilities.

My Pitch for Why This Matters

At the end of the day, most of us don't need or even want fancy frameworks. We want and need something that works.

I wanted to share this framework because this is what I'm starting to use as a practitioner - and it's helped me make sense of lots of organizations I've been involved with, from the company I work for to my family.

If you're someone - in any type of organization, large or small - I hope you find this very simple set of seven questions to help your organization perform better.

Making organizations better is hard, but it doesn't have to be complicated.

Organizations are energy processes

Can you imagine what organizations would be like if there was so much human energy created that it was “too cheap to meter”? None of the world’s problems would be out of reach. Not one.

When I have an organizational problem - like an underperforming team, or an organization that seems like it’s stuck - I just want a mental model to help me figure it out that is practical and simple to use. As a practitioner, what I care about is having something that works.

I found inspiration after reading a Works in Progress article about making energy too cheap to meter: organizations are energy processes which create, harness, and apply human energy. To solve organizational problems, all we need to do is improve how the organization creates and applies energy.

Photo Credit: Unsplash @pavement_special

When I say “energy processes”, I mean something like what I’ve outlined below. Take nuclear fission as an example. The end to end process for creating and applying nuclear energy happens in four steps:

Accumulate a fuel source (uranium) from which energy can be created

Create energy from the fuel source (i.e., using a nuclear reactor)

Harness and transmit the energy (create electricity via a steam turbine and deliver it to a plug in someone’s home)

Apply it to something of value (the electricity goes into a lamp which someone uses to read a favorite book after sunset)

Organizations, similarly, are an energy process:

The fuel that powers organizations are people and the ideas, information, expertise, and the motivation they bring to the table (i.e., like the uranium)

Organizations try to get their people to put forth effort that can be used to create something of value (i.e., like the nuclear reactor).

Organizations then create systems to harness the efforts of their people and channel it into collective goals (i.e., like the steam turbine and power lines)

The organization tries to ensure all the energy they’ve created goes into something that the end customer actually cares about, which they can be compensated for (i.e., like the reading lamp used to read a novel)

Thinking of organizations as energy processes can help us understand organizational challenges quickly and simply. When I have an organizational problem I can quickly ask myself these four questions, and determine where my organization’s issues lie:

Do we have enough “fuel” to create energy?

How much energy are we creating?

How much energy are we harnessing?

Are we applying our energy to something of value?

You can be the judge of whether this mental model is simple and useful. The rest of this post gives some detail on how to actually use the energy process model to diagnose an organizational problem.

Question 1: Do we have enough “fuel” to create energy?

One of my favorite questions to ask a teammate is: what percent of your potential impact do you feel like you are actually making? In my experience, most people are not even close to fully applying their skills, talents and ideas. A tremendous amount of potential is wasted in organizations.

To get a sense of whether there’s sufficient “fuel” in your organization or the degree to which potential is wasted, look for the following:

Complaints - if people are complaining, it means they have energy they’re not using and care enough to say something.

Regrettable losses - if people are leaving your company and getting good jobs and promotional opportunities elsewhere, at least one other organization seems something that you do not

Ask the team - people care about whether they’re wasting their time and energy. If you ask them, they’ll tell you if they have talents and energy that are being wasted

Ask yourself this question: if I assumed the people around me had talent, potential, and cared, would I be acting differently? If you answer that question with a “yes” it probably means you have more potential around you than you realize.

In my experience, it is almost never the case that an organization lacks sufficient “fuel” to create energy. Don’t shift the blame to the people around you, look inward first.

Question 2: How much energy are we creating?

I loved The Last Dance, the ESPN Films miniseries the 1997-1998 NBA Champion Chicago Bulls. It was remarkable to me how that team seemed to try so hard, and how Michael Jordan was able to be a catalyst, pulling tremendous amounts of energy from his teammates. Watching the documentary, the energy being created was obvious.

To get a sense of whether your organization is creating energy, look for the following::

Body language and non-verbals - If you work in an office, walk the floor and observe people through the windows of conference rooms, so you can’t hear what people are saying - just observe with your eyes. Do people seem like they want to be there or are trying very hard? Do they look bored? It’s pretty easy to see the parts of your organization that have energy just by being a fly on the wall and paying attention.

Experiments - When people are trying new things - whether its practices, sharing new ideas, or under the radar projects that nobody has asked for - it’s a good indication that energy is being created. It doesn’t have to be a grand novelty. I just had a colleague the other day, our team’s agile scrum master, that tried out a new framework for debriefing our bi-weekly sprint of work. He literally changed our four usual questions to four new questions. He just did it. I immediately thought, “our team has some energy and psychological safety if our scrum master is trying new things - this is awesome.”

Spontaneous Fun - I love to see teams that celebrate birthdays, bring snacks to work, create trivia games, or play pranks on each other. These are examples of activities that take energy that don’t have to occur to get the job done, they’re just for fun. If people are spending time putting energy toward having fun at work, it probably means they have plenty of energy for the work itself

Engagement Scores - Again, there are lots of survey companies that can help your organization execute a simple engagement survey. The ball don’t lie, and you can track engagement over time. If you have high engagement it probably means your organization is creating a lot of energy..

Question 3: How much energy are we harnessing?

One of my favorite bits of comedy is the Abbott and Costello, “Who’s on first?” skit. Nobody has any idea what’s going on and they have a pointless conversation with no conclusion. It’s hilarious to watch, and an excellent illustration of what it feels like when there’s lots of energy around but it’s not being channeled and applied.

To get a sense of whether your organization is effectively harnessing and applying energy, look for the following:

Low value work - In a factory setting, it can be easy to spot waste. In corporate offices, it’s harder to spot or prove inefficiency. Low value work is a good tell. If people don’t have anything better to do than low-value, non-impactful, work it probably means your organization isn’t harnessing energy well because it’s going into something that’s not worthwhile. When people have the opportunity to do something more impactful, they tend to.

“It’s not my job” - The phrase “it’s not my job” or when people toss work over the fence, it’s a strong indicator that someone, somewhere, doesn’t know what their job actually is or that they have any direction on what to do. If your organization is constantly trying to offload work to someone else, it probably means energy is being wasted and that there’s ambiguity around what matters and what doesn’t.

Silos and Bad Meetings - Every organization I’ve ever worked for has talked about how they’re “siloed” or that there are a lot of “useless meetings”. These are signs, again, that teams don’t know what they’re doing or know what the organization’s goal is. If people have the time to tolerate “silos” and “bad meetings” (which are easily fixed with clear goals and basic discipline), it probably means the organization isn’t harnessing energy well.

Sprint and Milestone Velocity: There’s a great concept from Agile called “sprint velocity”. It basically measures how much work (measured in “points” which are pre-assigned) the team was able to accomplish in a given amount of time, usually two weeks. When the sprint velocity rises, it means the team accomplished more with the same amount of time and resources invested. You don’t need to operate on a sprint team to use the concept - just look at how long simple things things - like making decisions, building presentations, or executing a contract - takes to complete. If you find yourself saying, “there has to be a faster way to do this” it probably means your organization isn’t harnessing and applying it’s energy effectively.

In my experience, organizations harness just a fraction of the energy they create. Sometimes all it takes it setting a clear goal and making it clear “who’s on first”.

Question 4: Are we applying our energy to something of value?

This area of the framework is where the stereotypical strategy and marketing questions come into play, like “where do we play”, “how do we win”, and “how are we differentiated”. To get a broad sense of whether your organization is in a virtuous cycle of value creation or a doom loop of commotodization, here are some quick heuristics to get a sense how bad your strategy issues are:

Revenue per employee or market share growth - if your organization’s revenue per employee or market share (or it’s equivalent) lags comparable industry players, you’re probably not doing something right - either you have energy problems further upstream, or, your organization is putting your energy into something people don’t actually care about.

Races to the bottom - if your company is trying harder and harder to grow, but you are constantly feeling downward pressure on prices, it probably isn’t providing a compelling product that people are happy to pay a premium for - because they get more than they pay for. If you feel like you’re in a race to the bottom, you need your customers more than they need you.

Customer feedback and referrals - This is obvious, if people are telling their friends about you or sending you thank you letters, it probably means you’re doing something of value to them - they’re literally marketing you for free. That willingness to show gratitude and spread the word means you’ve done something worthwhile for them.

That Works in Progress article I linked was so interesting, to me. I’ve been thinking about it for weeks. It suggested that something that disproportionally drives human progress is when energy becomes exponentially cheaper. What the author argued for was trying to make it so that energy was so clean, so cheap, and so abundant that it would be “too cheap to meter”.

Most of the time, organizations I’ve been part of miss the big picture about their organizational problems. Thinking through the lens of the energy process model brings this to light: the biggest opportunities for organizational energy are in creating it, not harnessing it.

To be sure, improving how we harness and apply energy matters - there’s opportunity at each phase of the organizational energy framework. But creating energy is the largest and most game breaking area to explore, by far.

Can you imagine what organizations would be like if there was so much human energy created that it was “too cheap to meter”? None of the world’s problems would be out of reach. Not one.

Creating Safe and Welcoming Cultures

The two strategies - providing special attention and treating everyone consistently well - need to be in tension.

To help people feel safe and welcome within a family, team, organization, or community, two general strategies are: special attention and consistent treatment.

Examining the tension between those two strategies is a simple, powerful lens for understanding and improving culture.

The Strategies

The first strategy is to provide special attention.

Under this view, everyone is special and everyone gets a turn in the spotlight. Every type of person gets an awareness month or some sort of special appreciation day - nobody is left out. Everyone’s flag gets a turn to fly on the flag pole. The best of the best - whether it’s for performance, representing values, or going through adversity - are recognized. We shine a light on the bright spots, to shape behaviors and norms.

And for those that aren’t the best of the best, they get the equivalent of a paper plate award - we find something to recognize, because everyone has a bright spot if only we look.

This strategy works because special attention makes people feel seen and acknowledged. And when we feel seen, we feel like we belong and can be ourselves.

But providing special attention has tradeoffs, as is the case with all strategies.

The first is that someone is always slipping through the cracks. We never quite can neatly capture everyone in a category to provide them special attention. It’s really hard to create a recognition day, for example, for every type of group in society. Lots of people live on the edges of groups and they are left out. When someone feels left out, the safe, welcoming culture we intended is never fully forged and rivalries form.

The second trade off is that special attention has diminishing marginal returns. The more ways we provide special attention, the less “special” that attention feels. Did you know, for example, that on June 4th (the day I’m writing this post) is National Old Maid’s day, National Corgi Day, and part of National Fishing and Boating week, plus many more? Outside of the big days like Mother’s Day and Father’s Day - how can someone possible feel seen and special if the identity they care about is obscure and celebrated on a recognition day that nobody even knows exists?

The existence of “National Old Maid’s day” is obviously a narrow example, but it illustrates a broader point: the shine of special attention wears off the more you do it, which leads to the more obscure folks in the community feeling less special and less visible, which breeds resentment.

The second strategy to create a feeling of safety and welcoming in a community is to treat everyone consistently well.

In this world everyone is treated fairly and with respect. Every interaction that happens in the community is fair, consistent, and kind. We don’t treat anyone with boastful attention, but we don’t demean anyone either. We have a high standard of honesty, integrity, and compassion that we apply consistently to every person we encounter..

The most powerful and elite don’t get special privileges - everyone in the family only gets one cookie and only after finishing dinner, the executives and the employees all get the same selection of coffee and lunch in the cafeteria, and we either celebrate the birthday of everyone on the team with cake or we celebrate nobody at all.

The strategy of treating everyone consistently well works because fairness and kindness makes people feel safe. When we’re in communities that behave consistently, the fear of being surprised with abuse fades away because our expectations and our reality are one, and we know that we will be treated fairly no matter who we are.

But this strategy of treating other consistently well also has two tradeoffs.

The first, is that it’s really hard. The level of empathy and humility required to treat everyone consistently well is enormous. The most powerful in a group have to basically relinquish the power and privilege of their social standing, which is uncommon. The boss, for example, has to be willing to give up the corner office and as parent’s we can’t say things like “the rules don’t apply to grown ups.” A culture of consistently well, needs leadership at every level and on every block. To pull that off is not only hard, it takes a long time and a lot of sacrifice.

The second tradeoff is that to create a culture of consistently well there are no days off. For a culture of consistently well to stick, it has to be, well, consistent. There are no cheat days where the big dog in the group is allowed to treat people like garbage. There are no exceptions to the idea of everyone treated fairly and with respect - it doesn’t matter if you don’t like them or they are weird. There is no such thing as a culture of treating people consistently well if it’s not 24/7/365.

The Tension

The answer to the question, “Well, which strategy should I use?” Is obvious: both. The problem is, the two approaches are in tension with each other. Providing special attention makes it harder to treat others consistently and vice versa. They key is to put the two strategies into play and let them moderate each other.

A good first step is to use the lenses of the two strategies to examine current practices:

Who is given special attention? Who is not?

Who doesn’t fit neatly into a category of identity or function? Who’s at risk of slipping through the cracks?

What do our practices around special attention say about who we are? Are those implicit value statements reflective of who we want to be?

What are the customs that are commonplace? How do we greet, communicate, and criticize each other?

Who is treated well? Who isn’t? Are differences in treatment justified?

How do the people with the most authority and status behave? Is it consistent? is it fair?

What are the processes and practices that affect people’s lives and feelings the most (e.g., hiring, firing, promotion, access to training)? Are those processes consistent? Are they fair? Do they live up to our highest ideals?

As I said, the real key is to utilize both strategies and think of them as a sort of check and balance on each other - special attention prevents consistency from creating homogeneity and consistency prevents special attention from becoming unfairly distributed.

From my observation, however, is that most organizations do not utilize these strategies in the appropriate balance. Usually, it’s because of an over-reliance on the strategy of providing special attention. That imbalance worries me.

I do understand why it happens. Providing special attention feels good to give and to receive and is tangible. It’s easy to deploy a recognition program or plan an appreciation day quickly. And most of all, speical attention strategies are scalable and have the potential to have huge reach if they “go viral.”

What I worry about is the overuse of special attention strategies and the negative externalities that creates. For example, all the special appreciation days and awareness months can feel like an arms race, at least to me. And, I personally feel the resentment that comes with slipping through the cracks and see that resentment in others, too.

Excessive praise and recognition makes me (and my kids, I think) into praise-hungry, externally-driven people. The ability to have likes on a post leads to a life of “doing it for the gram”. The externalities are real, and show up within families, teams, organizations, and communities.

At the same, I know it would be impractical and ineffective to focus one-dimensionally on creating cultures of consistently well. It’s important that we celebrate differences because we need to ensure our thoughts and communities stay diverse so we can solve complex problems. I worry that just creating a dominant culture without special attention, even one that’s rooted on the idea of treating people consistently well, would ultimately lead to homogeneity of perspective, values, skills, and ideologies instead of diversity.

The solution here is the paradoxical one, we can’t just utilize special attention or treating people consistently well to create safe and welcoming communities - we need to do both at the same time. Even though difficult, navigating this tension is well worth it because creating a family, team, organization, or community that feels safe and welcoming is a big deal. We can be our best selves, do our best work, and contribute the fullest extent of our talents when we feel psychological safety.