The mindset which underlies enduring marriages

For our marriages to survive and thrive - whether to our soulmate or not - we have to believe that life is better done together, not solo. No amount of love, destiny, resources, compatibility, or compromise can make up for not having this pre-requisite shift in mindset.

If our lives can be explained by the treasurers we adventure to find, one of my few holy grails is understanding how to be a soulmate. I search, everywhere I can, for little bits of the wisdom that can help Robyn have a marriage that endures for our whole life and for anything that exists after.

My perspective on marriage and soulmates has evolved, to something like this:

We start our lives with a paintbrush in our hands, and a blank canvas. And we start to wonder - what’s the most beautiful picture I can put on this canvas? What is the life I want to live? As we grow up we experiment a bit as we learn to paint.

Eventually, we get a pretty good idea of the most beautiful life we can paint on the canvas, and we go after it. We start to paint more feverishly as we hit our teens and twenties.

If we’re lucky, along the way we fall in love with someone. If we’re really lucky, we take a leap and marry them. And then the dynamic at the canvas changes.

A wedding, I think, is the moment two people start to paint onto one canvas. But here’s the the trick: the moment we say I do, we suddenly have to figure out how to paint while both holding the same brush.

And suddenly, were not only painting, we’re both trying to prevent the brush we’re both holding - our marriage - from breaking. It seems like there are three ways to survive this.

First, we could strengthen our brush and make it more resilient. In a marriage, there are times when each person is pulling in a different direction, and the brush has to be strong and resilient so it does not break. This strategy represents the body of advice people give about integrity, being faithful, committing to better/worse/richer/poorer/sickness/health, having a thick skin, continuing to date, rekindling love and romance, etc.

Second, we could learn to compromise. Maybe sometimes we paint the way I want to paint. Other times, we paint the way you want to paint. We never pull in different directions at the same time. By compromising, we put less tension on the brush. By putting less tension on the brush, it does not break as readily. This strategy represents the body of advice people give about conflict resolution and compromise.

Third, we could both imagine the painting we want to put on the canvas the same way in our heads. What do we want our lives to be like? What’s the beautiful picture we want to paint together? By having a shared vision for what we want our marriage and life to be, we don’t put stress on the brush because both our hands are moving in the same direction. This strategy represents the body of advice people give about shared values, shared vision, and growing together instead of apart.

Truthfully, every married couple needs to be good at all three of these approaches. Moreover, the first strategy of having a strong and resilient brush seems like a given. I don’t know how any marriage survives without that.

What struck me is that compromising seems to be the least optimal strategy here. Sure, every married couple has to compromise at some point and compromise a lot. Robyn and I compromise, too.

But how terrible would it be to have a lifetime full only of compromise? Either you are settling for the average your whole lives, and the painting you produce is the average, path of least resistance. Or, one person dominates, and one person gets the painting they think is beautiful and the other has lived someone else’s dream.

Compromise is necessary, but it seems best as a last resort. What seems much better is to just be on the same page about life together - and wanting to paint the same painting, constantly evolving with each brushstroke as life unfolds.

This metaphor reminds me of a fundamental tension within management. Teams - whether it’s at work, in sports, in government, or in community - fall apart if people care more about themselves than what the team is trying to accomplish together. So to in marriage.

If I care more about what I want life to look like than I care about painting our shared vision for the canvas, and painting it together our marriage will suffer. This is no different than any team - a team only endures if its members sacrifice to advance the aspirations of the team and evolve as the team evolves.

When I first began to think about soulmates, I thought it was a question of predestination. There was a soul out there, and through God’s will I was linked to that soul. All I had to do was find her. We’d fall in love. We’d work through problems. We’d put in the work for a great marriage, and after we departed this world we’d be committed to anything that came after.

And I did, thank God, find her. But my perspective on soulmates and marriage is different now. I don’t think that it’s only about this compromise, loving each other, keeping on dating, and putting in the work stuff anymore.

To be clear, I do still believe all those things - love, compromise, romance, and commitment - are required to be married and probably to be soulmates.

But because of my own experience being married and learning vicariously from hundreds of other couples, I now believe that there’s a key prerequisite to marriage and even being soulmates. It’s a mindset and orientation toward life that believes together is better.

We can’t just keep painting the canvas we started with prior to being married. We also can’t just find someone compatible, that we love and try to stitch our separate canvases together. We can’t even create a fully detailed blueprint for the canvas of our life and marriage, agree to it prior to a wedding, and never evolve it - life’s unpredictability certainly doesn’t permit that.

Instead, deep down, we have to fundamentally believe that the enterprise of painting a shared canvas, with a shared vision, using the same brush is what a beautiful life is. The critical prerequisite for marriage is that our mindset shifts from believing that the best way to live is being a solo artist, versus being part of a creative team.

No amount of love, destiny, resources, compatibility, or compromise can make up for not having this pre-requisite shift in mindset. For our marriages to survive and thrive - whether to our soulmate or not - we have to believe it’s better together.

The essential role of aunts and uncles

“Aunts” and “Uncles” build resilient cultures - whether it’s in a family or a larger organization.

I have come to appreciate aunts and uncles more lately, because now I see the effect that they have on our sons.

I am just in awe of how loved the boys feel by their aunts and uncles, whether they are blood-relatives or just close friends that care about our children as if they were blood family. And the love of an aunt or uncle is different than what we can give them, it’s something more generous perhaps. It’s as if the boys know, “you are not my parents, but you care about me and love me for who I am anyway, and that makes me feel safe and valued.”

Seeing the special love of aunts and uncles in the lives of our boys, has reminded me of my own aunts and uncles. I never could put words to it before, but I feel that same special, freely given, unconditional love from them. Thinking about it in retrospect, the love and support of my aunts and uncles has been a stabilizing force in my life.

I remember when my car broke down on the way into New York after college - miles away from the George Washington Bridge - and my Masi and Massasahib and extended family rescued me from a shady mechanic shop in the middle of North Jersey.

Or when my uncles in India deliberately ripped on American domestic policy to get a rise out of me and make sure I had some fire and fight in me. Or all our family friends who subtly reminded me I was a good kid in the middle of high school, by letting me sit and listen and hang out while they talked about scientific discovery, foreign affairs, or literature.

Or when Robyn’s aunts and uncles pulled me in and made me feel like part of the family, even from the very first family dinner I met them at by telling me stories and asking me questions. And they showed up at my father’s funeral as if they had known me my entire life.

I think what’s special about the love of aunts and uncles is that it’s redundant, affirming, and honest. It builds stability and resilience because it’s not the primary, day-in-day out sort of relationship you lean on. But it’s there, waiting to catch you, and to pick you up. And at times, it’s only an aunt or uncle who can really sit you down and get you out of the muck because they are able to have unconditional love but also enough distance and objectivity to call it like they see it.

It’s this combination of redundancy, affirmation, and honesty that makes aunts and uncles so important for a family’s culture. Theirs is a moderating influence that kicks in when things are going wrong.

And the more I think of it, the more I believe that every organization and community needs people who play the role of an aunt or uncle to thrive. In a company, for example, “aunts and uncles” are the people who take an active interest in you and give you advice, but don’t manage you directly. I can think of dozens of people who have been that sort of guide from afar, for me or others. When you mentor and develop others for whom you aren’t directly responsible, it’s such a gift to the culture of the company.

The same dynamic exists in a city. There are plenty of people who don’t have formal responsibilities over something but raise people up anyway. It could be neighbors who aren’t a block captain, but throw parties on their block and keep an eye out for neighborhood kids. It could be successful business owners who give advice behind the scenes to those coming up, outside of the auspices of business incubators and mentor programs. It could be the elderly couple in the church parish who invite newlywed couples to have dinner once or twice a year and help to nurture them through the ebbs and flows of marriage. These little acts are gifts that build the culture of a City and make the community more resilient. Which, it seems, is exactly like what aunts and uncles do.

I organize my life around three pillars - being a husband, father, and citizen. But what I’m realizing is that “uncle” is a really important role that fits within this framework, that I want to be intentional about - despite how invisible that role may be.

Snapping out of social comparison

I snapped out of the LinkedIn doom loop by thinking about the sacrifices a counterfactual world would’ve required.

When I’m stuck in a rut of feeling like I don’t measure up to others’ accomplishments, the advice of “remember how lucky you are” or “don’t compare yourself to others” or “focus on being the best possible version of you” just doesn’t work for me. It never has.

And in general I suppose those are good pieces of advice. They just don’t help me get out of a cycle of comparing my accomplishments to the people I went to school with or am friends with on LinkedIn.

Most Saturdays, these days at least, we go on a family walk. We live a few blocks away from a neighborhood coffee shop and we go after breakfast. Bo gets a hot chocolate with whipped cream, Robyn gets a coffee with milk, and I treat myself to a mocha - it is the weekend after all. Riley gets a extra long walk with extra time for smells and Myles is content just looking around and feeling the breeze go by as he rides in the stroller’s front seat.

And today, instead of trying to convince myself to stop feeling down about not being as accomplished as my peers, I started to wonder about trade-offs. After all, I made choices - for better or worse - that led to the spot I’m in today. And I wondered, if I had made different choices, what would I have had to sacrifice?

And I quickly realized, if I had made different choices that led to more professional success (which is mostly what drives my feelings of insufficiency, relative to my peers) I would’ve probably had to give up two things: living in Michigan and being a present husband and father. Which are two sacrifices I was absolutely not willing to make.

More or less, this was the thought exercise I went through:

And sure, after doing this exercise there were a few things that I regret and would do differently, like working harder on graduate school apps or sacrificing some of house budget for lawn care (I am irrationally embarrassed about how much crabgrass and brown patches we have on our lawn).

But by and large, thinking about the sacrifices making different choices would’ve required helped me to snap out of the doom loop of social comparison. Trying to ignore the feeling of not measuring up never works. Think about sacrifices and trade offs, was remarkably helpful.

If you also struggle with measuring yourself up to others’ accomplishments, I hope this reframing of the question is helpful to you too.

When I’m feeling used up

How I respond to feeling used up is a choice. It’s a choice. It’s a choice.

As a general rule, I don’t advocate for myself. It’s not that I avoid it or find it uncomfortable, I never really think to do it. The reason why, making a long story short, is that I’m a people-pleaser. I’m motivated more by making someone’s day than I am by a feeling of personal accomplishment.

To be clear, this is a personality flaw. Because I am a people-pleaser, I end up feeling used and used up a lot. Other people ask for my time and energy and my default position is to say yes, which leaves me feeling depleted.

This is a choice, with trade-offs.

How I respond when I feel used up is also a choice.

On the one hand, I could start saying no. I could protect my time and energy by setting boundaries.

On the other hand, I could insist upon reciprocity. Doing so would make day-to-day life more of a give-and-take rather than a mostly-give and sometimes take.

And seemingly paradoxically, I could give more. By digging deep and giving more, I could practice and get better at expanding the boundaries of my very little heart, and learn to give without receiving just a little more.

In reality, I should probably do some amount of all these things. Honestly though, I hope I don’t have to set boundaries or insist upon reciprocity. I hope instead that I can dig deep within and give more when I feel used up. I hope I’m dutiful enough to give to others, even if it means bearing more weight and sacrificing status or personal accomplishment.

I don’t know if the sinews of ethics and purpose holding me together can sustain that. I am definitely a mortal man, and not a saint. But still, I hope that I can dig deep and give more. It seems to be the choice most likely to create the world I hope to live in and leave behind.

But the revelation here is that it is indeed a choice. I feel so much pressure from our culture that the way to handle feeling used up are things like, “say no” or “self-care” or “manage your career” or “give and take” or “know your worth”.

And all that probably has a time and a place for mortal men like me. But that’s not the only choice. This choice is what I’ve found comforting.

Another way to handle feeling used is to live by wisdom like, “service is the rent we pay” or “nothing in the world takes the place of persistence”or “no man is a failure who has friends” or “be honest and kind” or “the fruits of your actions are not for your enjoyment”.

How I respond to feeling used up is a choice.

When our kids have hard days

I want to remember that the goal of parenting is not avoiding my own sadness.

The first words he said to me, as he had the purple towel draped generously over his wet hair and entire frame, were,

“It was a hard day, Papa.”

And then he melted into me, and I, on one knee, wrapped my arms around him and started to rub his back - both to help him dry off and comfort him. And we just stayed there, hugging on the bathroom floor for awhile.

And that’s one of the saddest type of moments I think I’ve had - when you’re kid is just sad. And yes even at three years old and change, he can have hard days and recognize that those days were hard.

And it wasn’t even that I felt and explosive, caustic sadness, where you feel the sadness growing and pushing out from core to skin. Like a sadness that smolders into my limbs and mind, and makes them feel like burning.

It was a depleting sadness, where I started to feel my heart shrinking, my bones and muscles hollowing, and my face and skin starting to feel...transparent maybe. It was a sadness that made me feel like I was disappearing.

When your own children - the ones you have a covenant with God and the universe to take care of - are truly sad, it’s a feeling you want to pass as quickly as possible, and never want to have again.

And when I realized that I “never want to feel this way again”, I started to get these two primal-feeling urges.

First I wanted to “fix it”. And “fixing it” has two benefits. First, it just stops this horrible feeling of depleting sadness. Because if I fix it, my son isn’t sad anymore, and therefore I’m not sad anymore.

But also, if I were the one who failed my son somehow and caused him to fall into this genuine sadness, fixing it is my redemption. Fixing the sadness is what helps me to feel like I’m not to blame. Because if I’ve fixed the external problem causing his sadness - the problem wasn’t me, it was that thing. Fixing it gives me the illusion that I’m the hero in this story, not the villain.

But beyond wanting to fix it, there was a more insidious urge, that crept on me slowly, was to believe this falsehood of, “maybe he’s just not ready” or “maybe we need to protect him more”.

And the fuzzy logic of that urge is this: If my kid is sad, there’s something out there that he can’t handle yet. And if I hold him back from going back out there, he’s less likely to have a hard day. Then he won’t be sad. And then I won’t feel this depleting sadness either.

But the problem with both of these responses is that if I find a way to let myself off the hook, it also deprives him of the opportunity to grow, and muddle his way through his sadness. Our kids will have hard days, and those days will suck. And on those days, we have to bring our best selves as parents. Because that’s when our kids need us to guide them, and love them, and coach them, and encourage them. And, many of those times we won’t be good enough; we will fail as parents and coaches. And they will have to muddle through that sadness for a longer. And we will feel depleted for longer, too.

But, damn. From those hard days, and that sadness, comes strength and confidence for our kids. Once they muddle through sadness, they have one more datapoint to add to their model to remind them that they can do this, they can figure this out, they can be themselves, they can be at peace, and they can rise up and through adversity.

And even though my instinct is to help my sons avoid sadness, I cannot let that instinct win. Because that instinct is selfish. What that motive truly is, is me wanting to avoid that horrible, depleting sadness that comes when your kids are sad.

Because these kids will have hard days. They will be sad. And even though my instinct is to make it stop as quickly as possible, and to never let this happen to them ever again, I must resist that selfish urge to fix their problems for them.

What I really need to do is comfort them, encourage them, love them, and coach them, and show them that no matter what happens I will be with them in this foxhole of sadness until they find a way out, no matter what.

And that I will be there, and support them in a way that doesn’t deprive them of the chance to come out of it stronger, kinder, and wiser.

Joy, Sacrifice, and Cattails

One day our sons will grow out of their find-joy-in-all-places mindset, and it will be my fault.

“These are cattails, Papa!”

When we were at the Metropark, I had another one of those moments where I can see the world through our sons’ eyes. “Dang,” I thought, “Bo finds joy, somehow, wherever he is.”

And I began to contemplate, how does he do that? Bo was as happy, peaceful, and silly-seeking as he ever is finding Cattails with Mommy and chasing Dadi around a tree, on this grassy pointe we were on at this lake, on an otherwise unremarkable Saturday morning.

And I was nostalgic, perhaps even a bit jealous as I watched him, laughing and enjoying the outside.

What happens to us along the way that makes it so that such little pleasures aren’t enough?

Later that week it hit me, one day our sons will grow out of this mindset too, and it will be my fault.

As they grow, I will teach them to sacrifice for the future. I will have no choice but to. Trade one cookie now for two cookies later sort of stuff. Or, study now so you can earn a living later. Or, that kid came a long way to play here, want to help him up the slide instead of going yourself?

All the examples, and more, are ones that hold the basic structure of: invest for the future so the future can be better, it will be worth the wait.

And that point of view, will probably lead to him believing that there’s more to life than cattails, so to speak.

As part of this growing up and learning to sacrifice, he will form beliefs on what “better” and “worth the wait” are. And my big gasp came when I realized that he will learn that from me.

As he learns to make sacrifice, his perceptions of why we should sacrifice will come from me. Should it be to lift up ourselves, or lift up others? Should we always strive for more? What is valuable, money and status? Character? Nature? Family? Being popular? Faith?

My example will dramatically influence what our boys will perceive as valuable and therefore what they sacrifice for.

I hope we can live up to that responsibility. And with any luck, at my age, Bo will still find joy in little things like cattails on a sunny day at the lake.

Here Comes the Sun

The Beatles song that comforts you, Here Comes the Sun, is a lovely tune. And it suits you.

We are a family that sings.

It has always been this way. When we first started dating, your mother and I would sing along to the radio when on car rides. And both of us grew up in households radiating with music, because your grandparents love music.

Even the city where we live, Detroit, has a musical history. Motown Music - which your mother and I adore - was one of the most beloved sub-genres of music in the 20th century, and originated just a few miles from our house.

Your older brother sings to you when you are crying, already, just like your mother and I do.

I love to sing to you. And as it happens, you and your brother love the Beatles. Each of you, from the time you were both a few weeks old, took a liking to a specific Beatles song. In those early newborn days, I would try singing anything to rock you both to sleep and the Beatles are what you both responded to.

The Beatles song that comforts you, Here Comes the Sun, is a lovely tune. And it suits you.

One of the best ways to describe your emerging personality is that it is sunny. Your mother would often say, even at a month or two old, that "Myles is just happy to be here." Your smile and disposition, my son, is warm and calming.

By many accounts, your birth came at a dark time in contemporary human history. Just a few weeks after you were born, the novel coronavirus began spreading rapidly across the world, causing the worst pandemic any living person has ever seen.

The economic fallout of worldwide quarantine was also the most significant economic disruption any living person has probably ever lived through. And just a few weeks ago, the murder of George Floyd at the hands of Minneapolis police sparked global protests of police violence and racism, which again, are unprecedented.

You arrived in our arms just in time for a truly exceptional time in history.

On the surface, then, the song that soothes you seems ironically timed. The coming of the springtime sun seems out of tune with the arrival of a global pandemic, depression, and episode of civil unrest. Indeed, when I first realized that Here Comes the Sun helped settle you for sleep, when I sang it to you I thought of it as a prayer. I wanted the long, cold, lonely winter to subside. I hoped for the sun to come, and soon.

But recently I've wondered if the timing of Here Comes the Sun rising to prominence in our lives was not a prayer, but rather a sign that a prayer was being answered.

You're too young to realize this, and I'm only starting to see this too. But there has been something interesting happening during this pandemic. In communities all across the world, including our own, I am seeing courage, compassion, leadership, and kindness to a degree I've never seen it before. People of all ages are making sacrifices. People in my age group, who are sarcastically characterized as being self-absorbed and indulgent, are leading with integrity and making sacrifices, too.

Through all the darkness and malaise of this pandemic I see rays of light. I see the beginnings of a change in mindset. What I pray for and hope for is that this pandemic shines a light on our culture and reminds us that we are capable of making sacrifices to solve difficult, existential problems. That we are capable of rising above adversity and petty differences.

And most of all, I see hope that in the next decades my contemporaries and I will choose to meet difficult, global challenges with courage and confidence instead of running from them.

For us, Myles, you were a prayer answered. And amidst all this struggle, your arrival here reminds me that the sun is, and always was, coming.

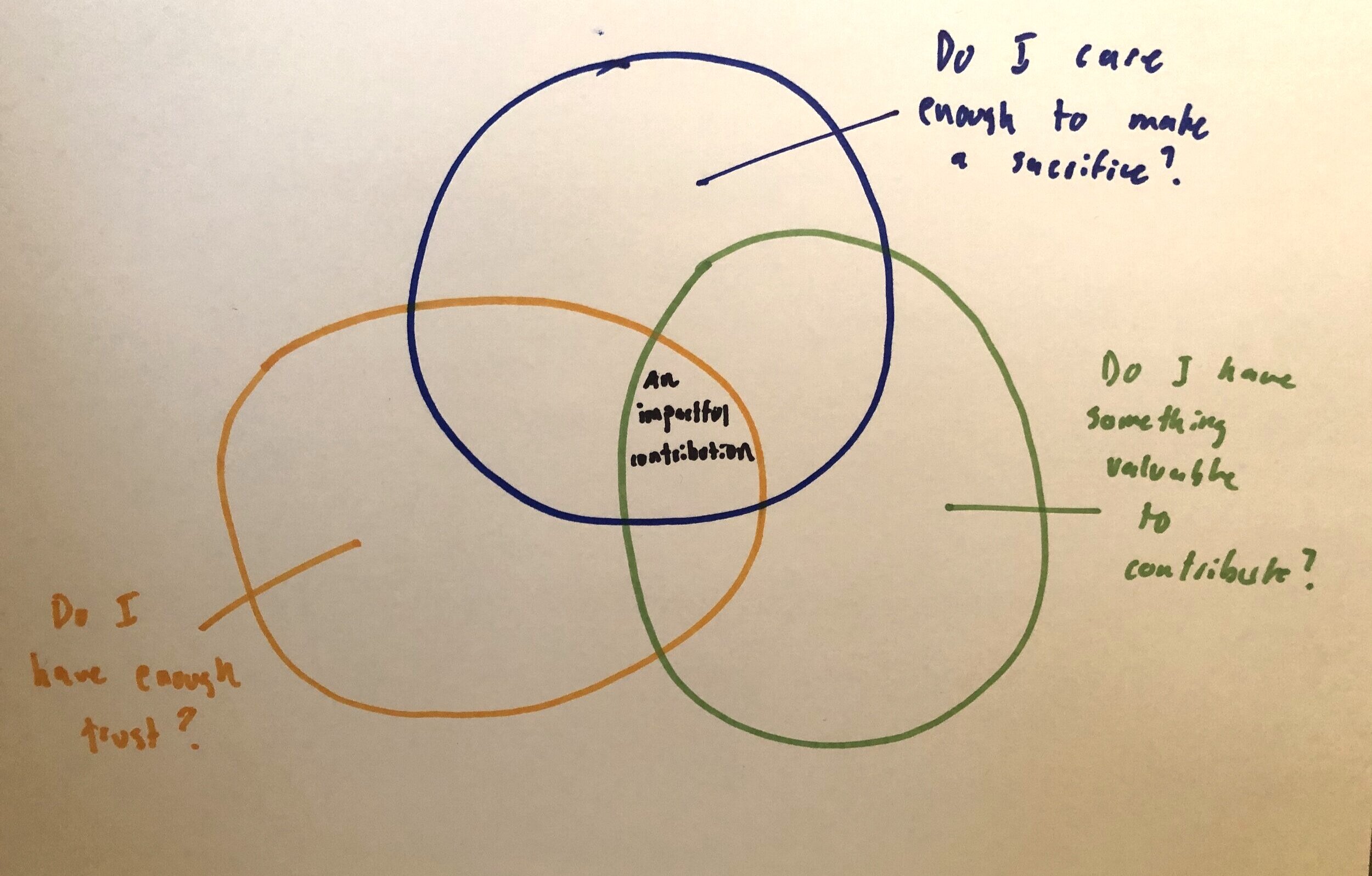

Impactful Contribution

When I’ve already committed to making an impactful contribution, what will I do?

This image of ikigai has been floating around the internet in various forms for a while.

And even though I’m generally skeptical of advice that emphasizes “doing what you love”, I don’t see any reason to criticize the concept the diagram argues for. Those four questions seem sensible enough to me when thinking broadly about the question of “what do I want to do with my life?”

Lately though, in the aftermath of George Floyd’s murder, as protests continue throughout our country, I’ve heard a lot of people ask - “what can I do?”

In this case, the question of “what can I do?” is not a decision where the framework of ikigai easily applies. When it comes to racial equity, if we’re asking the question of what can I do, we’re already committed to issue area and we aren’t expecting to be paid for it.

And this question is common. I have often asked myself, something like what do I want to do to contribute to others when I’m not at work? Nobody has unlimited leisure time, but most of us have some amount of time we want to use to serve others, after we complete our work and home responsibilities. We’re already committed to doing something for others, we just don’t know what to do.

So the question becomes: when I’ve already committed to making an impactful contribution, what will I do?

Here’s how i’ve been thinking about approaching that question lately:

There are three key questions to answer and find the intersection of:

Do I have enough trust to make an impactful contribution?

if so, where?

If not, how can I build it?

Do I have something valuable to contribute?

If so, what is it?

If not, what can I get better at that is helpful to others?

I I don’t know what’s helpful, how do I listen and learn?

Do I care enough (about anyone else) to make a sacrifice?

If so, who is it that I care so deeply about serving?

If not, how do I learn to love others enough to serve them?

Our decision calculus changes when we not trying to determine what to based on whether it will make us feel good. When we’re looking to serve others, it’s not as important to find something we are passionate about doing or finding something which helps us seem important and generous to our peers. What becomes most important is putting ourselves in a position to make an impactful contribution.

Because when we’ve already committed to making an impactful contribution, making that contribution is it’s own reward. We don’t depend as much on recognition to stay motivated. As long as we’re treated with respect, we’re probably just grateful for the opportunity to serve.