The Dynamic Leader: Parenting Lessons for Growing a Team

How often we adjust our style is a good leadership metric.

In both life and work, change isn't just inevitable; it is a vital metric for assessing growth. My experiences as a parent have led me to a deeper understanding of this concept, offering insights that are readily applicable in a leadership role.

Children Grow Unapologetically

As a parent, it’s now obvious to me that children are constantly evolving, forging paths into the unknown with a defiance that seems to fuel their growth. Despite a parent’s natural instinct to shield them, children have a way of pushing boundaries, a clear indicator that change is underway. This undying curiosity and defiance not only foster growth but necessitate a constant evolution in parenting styles.

Today, my youngest is venturing into the world as a wobbly walker, necessitating a shift in my approach to offer more freedom and encouragement, but with a ready stance to help our toddler the most dangerous falls. Meanwhile, my older sons are becoming more socially independent, which requires me to step back and allow them to resolve their disputes over toys themselves. It's evident; as they grow, my parenting style needs to adapt, setting a cycle of growth and adaptation in motion.

The Echo in Leadership

In reflecting on this, I couldn't help but notice the clear parallel to leadership in a corporate setting. A leader's adaptability to the changing dynamics of the team and the operating environment is critical in fostering a team's growth. If a leadership style remains static, it likely signals a team stuck on a plateau, not achieving its potential.

A stagnant leadership style not only hampers growth but fails the team. It is thus imperative for us as leaders to continually reassess and tweak their approach to leadership, ensuring alignment with the team's developmental stage and the broader organizational context.

This brings me to a critical question: how often should a leader change their style? While a high frequency of change can create instability, a leadership style untouched for years is a recipe for failure. A quarterly review strikes a reasonable balance, encouraging regular adjustments to foster growth without plunging the team into a state of constant flux.

Conclusion: The Dynamic Dimension of Leadership

In the evolving landscapes of parenting and leadership alike, adaptability emerges not just as a virtue but as a vital gauge of growth and effectiveness. Thanks to my kids, I was able to internalize this pivotal point of view: understanding the dynamic or static nature of one's approach is central to assessing leadership prowess.

For leaders eager to foster growth, the practice of self-assessment can be straightforward and significantly revealing. It is as simple as taking a moment during your team's quarterly goal reviews to ask, "How has the team grown this quarter?" and "How should my leadership style evolve to support our growth in the upcoming period?"

By making this practice a routine, we can ensure that our leadership styles remain dynamic, evolving hand in hand with our teams' developmental trajectories, promoting sustained growth and productivity.

Photo by Julián Amé on Unsplash

It is what it isn’t: surfacing struggles as a key leadership responsibility

To lead and move forward, we should think of common deflections as triggers to listen more deeply.

When we all use phrases like “it is what it is” or “I’m just tired” - portraying that we’re doing fine while masking our struggle.

And honestly, that actually seems rational. Talking about struggles is really hard! And most of the time, we don’t know if the person we’re talking to actually cares or is just interested in making small talk.

And so we use a phrase like, “it is what it is” and move on.

In our culture, we have lots of phrases like these, which have a double meaning - where we’re trying to suggest that we’re doing fine enough but are actually feeling the weight of something difficult.

But just because it’s rational, doesn’t mean we should use phrases like these and just move on - letting the struggle remain hidden.

And if we’re taking the responsibility to lead, whether at work or at home, surfacing and resolving struggles is part of our responsibility as leaders.

The difficult question is how. That’s what I’ve been reflecting on and what this post is about: how do we surface and help resolve struggles when it’s rational to mask them?

Surfacing Struggles

Luckily, we often use consistent turns of phrases when we are surfacing struggles. If we listen for those tells, we have a chance to double down when we hear them and try to learn more.

I asked a question on facebook this week to try generating a list of these phrases which create a subtle and believable facade. Thank you to anyone who shared their two cents, these were the examples folks shared:

“Living the dream.”

“I’m fine.”

“It’s going.”

“I am okay.”

“I’m hanging in there.”

“That’s life.”

“I’m here.”

“Another day in paradise.”

“Eff it.” (Used causally)

If we hear someone use phrases like these (or we say them ourselves) we can use it as a trigger to pause and explore, rather than as a cue to move on.

Surfacing Struggles With Kids

Kids are less obfuscating with their struggles, they come right out and share their little hearts out. They just struggle with being specific about their woes when then say or do stuff like:

“I can’t do this!”

“I’ll never figure this out!”

“This is too hard!”

[Screams and foot stomps]!

[Pterodactyl noises with hands over ears]!

“Poo-poo, poo-poo, POO-POO!”

“I forgot how to walk!” (My personal favorite from our kids)

With kids, these can be cues to pause, gather our patience and saddle up to emotional coach through some big feelings.

Surfacing Struggles At Work

At work, we’re more opaque, deftly deflecting and misdirecting with our words to make our inner struggles seem like obstacles outside our control. How often have you heard phrases like this?:

“We don’t have the resources.”

“We’re too busy.”

“It’s not our job.”

“We’ll just CYA and keep it moving.”

“We need to run this by the executive team first.” (or replace executive team with “legal”, “audit”, or “HR”)

“We’re breaking the guidelines set out in [insert name of esoteric poorly defined policy that’s only tangentially related to the issue at hand].”

At work, it’s so easy to take these phrases at face value and assume that there’s nothing to explore. But there usually is.

Once I started listening for them, I found that these phrases of deflection came up at home and at work, all the time.

Resolving Struggles

When others use subtle but believable facades to avoid or deflect from their struggles, the key is to decipher what they would actually be saying if they felt like they could be honest and vulnerable.

If we can figure that out, we can meet the person in front of us (or ourselves in the mirror) where they are, understand their true needs, and then help them deal with their struggles.

When someone uses a subtle but believable deflection, they usually, deep down, mean something like this:

“I’m overwhelmed. There’s so much happening and I can’t even figure out where to start.”

“I’m scared. Things are not going well and I don’t know whether the future will be better.”

“I don’t trust you. I need you to give me reasons to put my faith in you.”

“I’m stuck. I’ve been trying to make this better but nothing seems to make a difference. I need help.”

“I feel alone. I don’t feel the support of other people on this very difficult thing we’re going through.”

“I don’t believe in myself. I need convincing that you won’t let me fail.”

“I don’t care. To keep going, I need to feel like what we’re doing actually matters.”

“I don’t trust our group. I’ve been let down before and I don’t want to be hurt again.”

“I’m confused. I don’t know what to do or what’s expected of me.”

“I’m ashamed. I need to feel included and that my behaviors don’t make my worth conditional.”

“I feel guilty. I need encouragement and guidance that I can do better.”

“I feel like I’m in danger. I need you to help me feel safe.”

If we discover the real root feeling or struggle, the posture we need to take is relatively straightforward. It’s rarely an easy struggle, but if we know what the person in front of us is actually dealing with, we actually have a chance to be helpful to them. If we don’t understand, we definitely won’t be helpful, even if we’re well-intentioned and try really hard.

Practical Skills Matter: Listening, Integrity, Compassion

The practical lesson that I’ve learned is twofold.

First, we need to listen very carefully for these very subtle deflections and instead of being fooled by them, we need to sharpen our focus. We need to pause and graciously lean in. These deflections are really tells that the person in front of us, or ourselves if we say them out loud, are actually struggling.

Second, we need to find a way to hear precisely what the person in front of us is having a hard time saying. That can happen in one of two ways. We either have to listen and observe very carefully, or, we need to show integrity and compassion so unflinchingly and consistently that the person in front of us feels safe enough to tell the truth.

Conclusions

Beyond the practical tools around how to surface and resolve struggles, there’s a broader point that’s important to make: we have a choice to make.

On the one hand, one could completely reject my point of view. Someone could say, “I’m not responsible for helping every person in front of me with every single one of their struggles. They need to suck it up, they need to figure some of this out on their own. They need to take responsibility for their own struggles, that’s not fully on me.”

Maybe that’s true, at least to some degree. In my life, I’ve found it impossible to help someone who’s not enrolled in the journey of finding a better way. And, it’s also true that we have practical limits. We as individuals can’t possibly do this all ourselves - there’s not enough time or energy available to us to take every struggle of the people we care about onto our shoulders alone.

But at the same time, I believe we need to try because we owe it to each other. We have all struggled. We have all needed someone to help us surface and resolve our struggles. We all have been helped, by someone, at some time. Nobody in this world has done it alone.

And if we want to move forward - whether it’s with our kids at home or with our colleagues at work - someone has to be responsible for it.

So when someone in our orbit next says something like, “it is what it is” or “I’m just tired” I hope we all choose to say something like, “oh really, what do you mean?” Instead of letting the conversation pass as if nothing happened.

That’s the choice we have ahead of us. Let’s choose to listen deeply.

Photo by Christina Spiliotopoulou on Unsplash

My Dream: Bringing CX to State and Local Government

Bringing CX to State and Local Government would be a game-changer for everyday people.

My number one mission for my professional life is to help government organizations become high performing. If every government were high performing, I think it would change the trajectory of human history for the better in a big way.

One way to do that is to bring customer experience (CX) principles pioneered in the private sector and some forward thinking places (like the US Federal Government, the UK Government, or the Government of Estonia) and bring them to State and Local Government.

It is my dream to create CX capabilities in City and State Government in Michigan and have our state be a model for how CX can work at the State and Local level across the country.

Dreams don’t come true unless you talk about them. So I’m talking about it.

If you have the same mission or the same dream, I want to meet you. If you have friends or colleagues who have similar missions or dream, I want to meet them too. We who care about high performing, citizen-centric government want to make this happen. I want to play the role that I can play to bring CX to State and Local Government and I want to help you on your journey. Full stop.

I have so much more to say about what this could be, but I had to start somewhere. I had ChatGPT help me take some thoughts in my head and convert them into a Team Charter and a Job Description for the head of that team.

What do you think? Have you seen this? What would work? What’s missing? Maybe we can make something happen together, which is exactly why I’m putting a tiny morsel of this idea out there for those who care to react to.

The country and world are already moving to more responsive, networked, citizen-centric models of how government can work. Let’s hasten that transformation by bringing CX principles to the work our City and State Governments do every day.

I can’t wait to hear from you.

-Neil

—

Team Charter for Customer Experience (CX) Improvement in City or State Government

Purpose (Why?)

To transform and enhance the quality of government services and citizens’ daily life through CX methodologies. High impact domains include touchpoints with significant impact for the citizens who are engaged (e.g., support for impoverished families obtaining benefits) and those touchpoints affecting all citizens (e.g., tax payments, vehicular transportation), and touchpoints with high community interest.

Objectives (What Result Are We Trying to Create?)

Increase citizen satisfaction

Strengthen trust in government

Elevate the quality of life for residents, visitors, and businesses

Scope (What?)

This initiative will focus on the top 5-7 stakeholders personas driving the most value to start:

Improve how citizens experience government services, daily life, and vital community aspects

Drive change cross-functionally and at scale across interaction channels

Foster tangible improvements in the quality of life

Create and align KPIs with community priorities and establish ways to measure and communicate success

Activities (How?)

Segment residents, visitors, businesses, and identify top personas and touchpoints

Develop customer personas, journey maps, and choose highest-value problem areas to focus on for each persona

Prioritize and create an improvement roadmap

Partner with various stakeholders to drive change

Measure results, gather feedback, and align with community priorities

Share progress regularly and communicate value to stakeholders to gain momentum and support

Team and Key Stakeholders (Who?)

Leadership: A head with experience in leadership, CX methods, data, technology, innovation, and intrapreneurship

Department Liaisons: Individuals driving CX within different governmental departments

External Partners: Collaboration with other government agencies, citizen groups, foundations, the business community, and vendors

Core Team: A mix of professionals with expertise in relationship management, digital, innovation, leadership, and related fields

Timeline and Next Steps (When?)

0-6 Months: Segmentation, personas, and journey mapping

6-12 Months: Problem analysis and a prioritized roadmap creation

9-18 Months: Tangible improvements and iterative changes in focus areas

Ongoing: Continual refinement and adaptation to changing needs and priorities

—

Job Description: CX Improvement Team Leader

Position Overview:

As the CX Improvement Team Leader for City or State Government, you will drive transformative change to enhance citizens’ experience with government services and improve quality of life for citizens in this community. You will guide a cross-functional team to create innovative solutions, aligning with community priorities and creating tangible improvements in quality of life.

Responsibilities:

Lead and inspire a diverse team to achieve objectives

Create and align KPIs, establish methods for measurement

Develop and execute an improvement roadmap

Engage with stakeholders across government agencies, citizen groups, businesses, and more

Regularly share progress and communicate the value of initiatives to gain momentum and support

Collaborate with external partners and vendors as needed

Foster an innovative and responsive culture within the team

Qualifications:

Minimum of 10 years of experience in customer experience, leadership, technology, innovation, or related fields

Proven ability to drive change at scale across various channels

Strong communication and relationship management skills

Experience in government, public policy, or community engagement is preferred

A visionary leader with a passion for improving lives and a commitment to public service

Photo by NordWood Themes on Unsplash

A practitioner’s take on goals and dreams

There’s a time for SMART and there’s a time for something bigger.

There is a time and a place for SMART goals.

Like when we want or have to achieve something that’s specific, measurable, attainable, relevant, and timely. (See what I did there?)

Put another way, sometimes we need to outline a goal like this: “I will publish my book in 2023, and have 1000 people download or purchase it within 6 months of publication.”

But there are times when SMART goals are precisely the wrong approach to take.

Sometimes we have to dream. And a good dream is probably the inverse of a SMART goal: A audacious, unorthodox, and slow to achieve.

Put another way, sometimes we need to put a dream out there, something like: “I dream about a day when America is a more trusting place, probably because our government is innovative and citizen centric, we have skilled leaders on every block, and our culture becomes one where everyone reflects on their own actions and is committed to developing their own character.”

Here’s what I’ve learned about both, as a real person, living a real life, trying to achieve goals and dreams for real:

First, dreams are a paradox. The most visionary dream feel too crazy to talk about - and so we often don’t talk about them. At the same time, the surest way to never achieve a dream is to keep it a secret. The only way our dreams become a reality is if we talk about them even when it feels awkward.

Second, it’s really important to know whether the situation at hand requires a goal or a dream. If the situation is well understood and we need to “get it done”…goals all day.

But if we’re trying to imagine a better future, and contemplate a new way of being, dreams are the only way.

Third, both goals and dreams are worthless if they are not specific. If the finish line is blurry, collective action grinds to a halt, especially when there’s no hierarchy to scare people into action.

Finally, and perhaps most importantly, both dreams and goals require an action which deviates from the status quo. That’s why we dream and set goals in the first place, we want something to be different.

A good question is: “Do my goals and dreams require me to act differently? If so, how? If not, how do I get better goals and dreams?”

That’s there’s the unlock.

Photo by Estee Janssens on Unsplash.

Leaders must create profound silence

Imagine walking into a bustling coffee shop. The whirring of espresso machines, heated debates over the latest news, and the clatter of cups and saucers create an overwhelming din. Now, imagine if all those noises were amplified by a microphone and broadcast over a loudspeaker as you sipped your coffee.

But finally, imagine if someone in the middle of this chaos could flick a switch, transforming the noise into a hum, the hum into a whisper, and finally, the whisper into silence. Suddenly, in the quiet, you can hear the person next to you, the words of a book being read aloud, or even your own thoughts. This is the power of creating silence.

We live in a world of ceaseless noise. At work, we often find that the louder we are – the more assertive in meetings, the more vocal in lobbying for promotions, the more boisterous in attracting customers and followers – the more recognition we receive. Particularly in large organizations, there's a perceived correlation between the volume of one's voice and the likelihood of reward.

Likewise, our family and community lives are marked by volume, though less as an incentive and more as a trap. Community meetings frequently devolve into verbal contests of who can yell the loudest. As parents, we often get swept up in hectic schedules and an unending flood of information, resorting to yelling out of sheer desperation to keep things under control.

Then there's social media, which amplifies this noise to near-deafening levels. It equips everyone with a microphone, fostering an environment that rewards those who shout the loudest. I'm not criticizing influencers or social media—a trend that's fashionable to critique these days. I'm merely labeling our day-to-day American life for what it is: incredibly loud.

The usual advice is to promote listening, to foster better listeners in this noisy world. But listening, as underrated as it is, may not suffice. Amid the cacophony of voices and plethora of microphones, effective listening becomes an Everest to climb. What we need, in professional settings, at home, or within our communities, is the ability to create silence.

Creating silence differs from listening. Listening involves one person attentively comprehending and empathizing with another—a personal act. On the other hand, creating silence entails reducing the ambient noise, enabling everyone in that space to hear and listen. While listening is a two-person tango, creating silence resembles providing noise-cancelling headphones for the entire room.

So, what does 'creating silence' look like? At work, it might be the pause in a meeting that encourages thoughtful responses, allowing even the quietest person to be heard and respected. It could be a company creating a safe space for critical feedback or praise from its customers and partners. It's the breakthrough idea emerging during a moment of quiet reflection in a workshop. It's a team communicating so effectively that members eagerly anticipate meetings or even deem them unnecessary.

In our homes and communities, creating silence might be even more crucial. It happens when those in power amplify the voices of the less powerful—be it our children or marginalized groups. It's when community leaders stay calm and receptive, encouraging constructive dialogues even when faced with challenging questions. It's the genuine connection made during a family dinner where everyone feels comfortable enough to discuss their week, free from platitudes and arguments.

Creating silence requires a particular kind of swagger—not an arrogant narcissism, but a quiet confidence stemming from self-belief and humility. Only when we are secure within ourselves can we create the silence that allows others to flourish.

Creating silence isn't without challenges, though. It could be misconstrued as suppressing voices or dismissing dissent. In our quest for quiet, we might unintentionally stifle vibrant discussion or inhibit creative conflict. The genuine creation of silence isn't about muffling noise but about cultivating an environment where every voice gets a chance to be heard without being drowned out. It's about discerning when to speak, when to listen, and when to simply relish the silence.

There's also a risk of silence being associated with absence or inactivity. In our fast-paced world, we're conditioned to see quiet as wasted time or empty space needing to be filled. We must remember that silence isn't emptiness but a space full of potential. In silence, we find room to think, reflect, and connect on a deeper level.

Perhaps the concept of creating silence has never been as vital as it is now, given our world's unprecedented noise levels. And why is it so crucial? Because silence makes space for collaboration and connection. We can't collaborate or build relationships unless we hear each other. Even the best listener can't function if they can't hear. That's why we must create silence.

So, where do we start? Like most things, we start with ourselves. We begin by creating silence within our own minds. We can work to silence catchy songs, the hum of to-do lists, or our own inner critics. Whether it's through meditation, self-expression, therapy, or exercise, we need to create silence so we can listen to ourselves.

But we mustn't stop there. Our teams, families, and communities need us to create enough silence so that the shouting subsides. Then we can stop worrying about being heard and truly begin to listen.

As we learn to create this silence, let's maintain an open dialogue about what works and what doesn't. Because in a world that's becoming louder, it's not just about who can shout the loudest, but also about who can create the most profound silence.

How to build a Superteam

Superteams don’t just achieve hard goals, they elevate the performance of teams they collaborate with.

In today's dynamic business landscape, the concept of building high-performing teams and managing change has been extensively discussed in management and organization courses.

However, as I've gained real-world experience, I've come to realize that the messy reality we face as leaders is far different from the pristine case studies we encountered in school. Collaborating with other teams, even within high-performing organizations, presents unique challenges that demand a fresh perspective.

The Dilemma of Collaboration for High-Performing Teams

As high-performing teams, we often find ourselves operating within larger enterprises, requiring collaboration with teams from other departments and divisions. However, the reality is that not all these teams are high-performing themselves, which poses a significant challenge. Most enterprises lack the luxury of elite talent, and even the most high-performing teams can burn out if burdened with carrying the weight of others.

Over time, organizations tend to regress to the mean, losing their edge and succumbing to stagnation. If we truly aspire to change our companies, communities, markets, or even the world, simply building high-performing teams is not enough. We must contemplate the purpose of a team more broadly and ambitiously.

What we need are Superteams.

As I define it, a Superteam meets two criteria:

A Superteam is a high-performing team that's able to achieve difficult, aspirational goals.

A Superteam elevates the performance of other teams in their ecosystem (e.g., their enterprise, their community, their industry, etc.).

To be clear, I mean this stringently. Superteams not only fulfill their own objectives and deliver what they signed up for but also export their culture. Through doing their work, Superteams create a halo that elevates the performances of the people and partners they collaborate with. They don't regress to the mean; they raise the mean. Superteams, in essence, create a feedback loop of positive culture that is essential to make change at the scale of entire ecosystems.

One way to think of this is the difference between a race to the bottom and a race to the top. In a race to the bottom, the lowest-performing teams in an ecosystem become the bottlenecks. Without intervention, these low-performing teams repeatedly impede progress, wearing down even high-performing teams. Eventually, the enterprise performs to the level of that sclerotic department. This is the norm, the race to the bottom where organizations get stale and regress to the mean.

Superteams change this dynamic. They export their culture to those low-performing teams that are usually the bottlenecks in the organization, making them slightly better. This improvement gets, reinforced, and creates a transformative, positive feedback loop. As other teams achieve more, confidence in the lower-performing department grows. This is the race to the top, where raising the mean becomes possible.

The biggest beneficiary of this feedback loop, however, is not the lower-performing team—it's actually the Superteam itself. Once they elevate the teams around them, Superteams can push the boundaries even further, reinvesting their efforts in pushing the bar higher. This constant pushing of the boundary raises the mean for everyone, ultimately changing the ecosystem and the world.

How to Build a Superteam

The first step to building a Superteam is to establish a high-performing team that consistently achieves its goals. Moreover, a Superteam cannot have a toxic culture since it is difficult, unsustainable, and dangerous to export such a culture.

Scholars such as Adam Grant, who emphasizes the importance of fostering a culture of collaboration, have extensively studied how to build high-performing teams with positive cultures. Drawing from their work, particularly in positive organizational scholarship, we can further expand our understanding of Superteams.

In addition to the exceptional work of these scholars, it is essential to focus on the second criterion for a Superteam: elevating the performance of other teams in the ecosystem. How can a team work in a way that raises the performance of others they collaborate with? To achieve this, I propose four behaviors that make a significant difference.

First, a Superteam must act with positive deviance. Superteams should feel materially different from average teams in its ecosystem. Whether in composition, meeting structures, celebration of success, language, or bringing energy and fun, Superteams challenge conventions. Such explicit differences not only generate above-average results but also create a safe space for others to act differently.

Second, a Superteam must be self-reflective and constantly strive to understand and improve how it works. Holding retrospectives, conducting after-action reviews, or relentlessly measuring results and gathering customer feedback allows Superteams to make adjustments and changes with agility. This understanding of internal mechanics and the ability to transmit tacit knowledge of the culture enable every team member to become an exporter of the Superteam's culture.

Third, a Superteam walks the line between open and closed, maintaining a semi-permeable boundary. While being open and transparent is crucial for exporting the team's culture, maintaining a strong boundary is equally important. Being overly collaborative or influenced by the prevailing culture can hinder positive deviance. Striking the right balance allows Superteams to create space for exporting their culture while protecting it from easy corruption.

Finally, a Superteam must act with uncommon humility and orientation to purpose. By embracing the belief that "you can accomplish a lot more when you don't care who gets the credit," Superteams prioritize the greater purpose of raising the mean instead of seeking personal recognition. This humility allows them to make cultural improvements without expecting individual accolades, empowering others to adopt and embrace the exported culture.

Over the years, I've become skeptical of mere "culture change initiatives." True culture change requires more than rah-rah speeches and company-wide emails. Culture change demands role modeling and the deliberate cultivation of Superteams. Any team within an ecosystem can change its culture and aspire to build Superteams that export their culture, ultimately transforming the world around them for the better.

Leadership in the Era of AI

When it comes to the impact of Generative AI on leadership, the sky's the limit. Let's dream BIG.

Just as the invention of the wheel revolutionized transportation and societies thousands of years ago, we might actually stand on the brink of a new era. One where generative AI, like ChatGPT, could transform our way of life and our economy. The potential impact of AI on human societies remains uncharted, yet it could prove to be as significant as the wheel, if not more so.

Let's delve into this analogy. If you were tasked to move dirt from one place to another, initially, you would use a shovel, moving one shovelful at a time. Then, the wheel gets invented. This innovation gives birth to the wheelbarrow—a simple bucket placed atop a wheel—enabling you to carry 10 or 15 shovelfuls at once, and even transport dirt beyond your yard.

But, as we know, the wheel didn't stop at wheelbarrows. It set the stage for a myriad of transportation advancements from horse-drawn buggies, automobiles, semi-trucks, to trains. Now, we can move dirt by the millions of shovelfuls across thousands of miles. This monumental shift took thousands of years, but the exponential impact of the wheel on humanity is undeniable.

Like the wheel, generative AI could be a foundational invention. Already, people are starting to build wheelbarrow-like applications on top of generative AI, with small but impactful use cases emerging seemingly every day: like in computer programming, songwriting, or medical diagnosis.

This is only the beginning, much like the initial advent of the wheelbarrow. Just as the wheelbarrow was a precursor to larger transportation modes, these initial applications of generative AI mark the start of much more profound implications in various domains.

One area in particular where I'm excited to see this potential unfold is leadership. As we stand on the brink of this new era, we find ourselves transitioning from a leadership style that can only influence what we touch, constrained by our own time. Many of us live "meeting to meeting", unable to manage a team of more than 7-10 people directly. Even good systems can only help so much in exceeding linear growth in team performance.

However, with the advent of generative AI, we're embarking on a new journey, akin to moving from the shovel to the wheelbarrow. Tools like ChatGPT can serve as our new 'wheel', helping us leverage our leadership abilities. In my own experiments, I've seen some promising beginnings:

A project manager can use ChatGPT to create a project charter that scopes out a new project outside their primary domain of expertise. This can be done at a higher quality and in one quarter or one tenth of the usual time.

A product manager can transcribe a meeting and use ChatGPT to create user stories for an agile backlog. They could also quickly develop or refine a product vision, roadmap, and OKRs for annual planning—achieving higher quality in a fraction of the time.

A people leader can use ChatGPT as a coach to improve their ability to lead a team, relying on the tool as an executive coach to boost their people leadership skills faster and more cost-effectively than was possible before.

These are merely the wheelbarrow-phase applications of generative AI applied to leadership. Now, let's imagine the potential for '18-wheeler' level impact. Given the pace of AI development, it's plausible that this kind of 100x or 1000x impact on leadership could be realized in mere decades, or possibly even years:

Imagine a project manager using AI to manage hundreds of geographically distributed teams across the globe, all working on life-saving interventions like installing mosquito nets or sanitation systems. If an AI assistant could automatically communicate with teams by monitoring their communications, asking for updates, and creating risk-alleviating recommendations for a human to review, a project manager could focus on solving only the most complex problems, instead of 'herding cats.'

Consider a product manager who could ingest data on product usage and customer feedback. The AI could not only assist with administrative work like drafting user stories, but also identify the highest-value problems to solve for customers, brainstorm technical solutions leading to breakthrough features, create low-fidelity digital prototypes for user testing, and even actively participate in a sprint retrospective with ideas on how to improve team velocity.

Envision a people leader who could help their teams set up their own personal AI coaches. These AI coaches could observe team members and provide them with direct, unbiased feedback on their performance in real time. If all performance data were anonymized and aggregated, a company could identify strategies for improving the enterprise’s management systems and match every person people to the projects and tasks they can thrive, and are best suited for, and actually enjoy.

Nobody has invented this future, yet. But the potential is there. What if we could increase the return on investment in leadership not by 2x or 5x, but by 50x or 100x? What if the quality of leadership, across all sectors, was 50 to 100 times better than it is today?

We should be dreaming big. It's uncertain whether generative AI will be as impactful as the wheel, but imagining the possibilities is the first step towards making them a reality.

Generative AI holds the potential to revolutionize not only computer programming but also leadership. Such a revolutionary improvement in leadership could lead to a drastically improved world.

When it comes to the impact of Generative AI on leadership, the sky's the limit. Let's dream BIG.

Photo by Ēriks Irmejs on Unsplash

The Leadership Trifecta: Management, Leadership, Authorship

What matters is the nuance, because the three affect dynamics at different levels of organization: management affects individual dynamics, leadership affects team dynamics, and authorship affects ecosystem dynamics.

When we choose to lead, the first question we must answer is: who are we leading for?

Are we choosing to lead to enrich ourselves or everyone? Are we doing this for higher pay, social status, career advancement, and spoils? Or, are we doing this to improve welfare for everyone, enhance freedom and inclusion, or better the community?

If you're not in it for everyone (including yourself, but not exclusively or above others), you might as well stop reading. I am not your guy - there are plenty of others who have better ideas about power, career advancement, or gaining increased social status.

But if you're in it for everyone, if you're willing to take the difficult path to do the right thing for everyone in the right way, you probably struggle with the same questions I do, including this big one: what does choosing to lead even entail? Do I need to lead or manage? What am I even trying to do?

Is the goal management or leadership?

For many years, I’ve rolled my eyes whenever someone starts talking about leadership versus management or how we need people to transcend from being “managers” and elevate their game to become “leaders.” In my head, I'd question anytime this leadership vs. management paradigm comes up: “what are we even talking about?”

After many years, I finally have a point of view on this tired dialogue: management, leadership, and authorship all matter. What matters is the nuance, because the three affect dynamics at different levels of organization: management affects individual dynamics, leadership affects team dynamics, and authorship affects ecosystem dynamics.

Management, Leadership, and Authorship

Management, though the term itself is not what matters, can be defined as the practice of influencing individual performance. Think "1 on 1" when considering management. In management mode, the goal is to ensure that every individual is contributing their utmost.

Management primarily influences individual dynamics. Hence, when discussing management, we often refer to directing work, coaching, providing feedback, and developing talent. These are the elements that shape individual performance.

Similarly, leadership can be viewed as the practice of enhancing team performance as a collective unit. Think "the sum is greater than its parts" when contemplating leadership. In leadership mode, the goal is to ensure the team can make the highest possible contribution as a single unit.

Leadership predominantly affects team dynamics, which is why discussions about leadership often involve vision, strategy, culture, and processes. These elements impact the performance of a team functioning as a single unit.

Authorship, however, is the practice of influencing the performance of an entire network of teams and organizations aiming to achieve collective impact, often without formal or centralized coordination.

Authorship has become more feasible in recent history due to the rise of the internet. Unlike 50 years ago, many of us now have the opportunity to consider authorship because we can communicate with entire networks of people.

When considering authorship, think of it as being part of a movement that's larger than ourselves. In authorship mode, the goal is to mobilize an entire network to benefit an entire ecosystem - whether it's an industry, a community, a specific social issue or constituency, or in some cases, society as a whole. The aim is to ensure that the entire network is making the highest possible positive contribution to its focused ecosystem.

Authorship primarily affects ecosystem dynamics. That's why, when I ponder authorship, I think about concepts like purpose, narratives, opportunity structures, platforms, and shaping strategies. These elements influence entire networks and mobilize them to create a collective impact, particularly when they're not part of the same formal organization.

To illustrate, consider a software development company. In the context of management, the team lead may ensure every developer is performing at their best by providing guidance, setting clear expectations, and offering constructive feedback.

When it comes to leadership, the same team lead would be responsible for setting the vision for their team, aligning it with the company's goals, creating a positive team culture, and facilitating effective communication.

Authorship, however, would usually (but not necessarily) involve the CEO or top management. They would work towards building industry partnerships, contributing to open-source projects, or organizing industry conferences, ultimately aiming to influence the broader tech ecosystem, perhaps to achieve a broader aim like improving growth in their industry or solving a social problem - like privacy or social cohesion - through technology.

It all boils down to three questions:

Management question: On a scale of 1 to 100 how much of my potential to make a positive impact am I actually making?

Leadership question: On a scale of 1 to 100, how much of our team’s potential to make a positive impact are we actually making?

Authorship question: On a scale of 1 to 100, how much of our potential positive impact are we making, together with our partners, on our ecosystem or the broader world?

To assess your potential impact on a scale from 1 to 100, start by understanding the maximum positive impact you, your team, or your ecosystem could theoretically achieve. This '100' could be based on benchmarks, best practices, or even ambitious goals. Then, honestly evaluate how close you are to that maximum potential. This is not a perfect science and will require introspection, feedback, and perhaps even some experimentation. The important thing is to have a reference point that helps you understand where you are and where you could go.

In my own practice of leading, these are the questions I have been starting to ask myself and others. These three questions are incredibly helpful and revealing if answered honestly.

To really make a positive impact, I’ve found that it’s important to ensure all three dynamics - individual, team, and ecosystem - are examined honestly. If we truly are doing this to benefit everyone (ourselves included) we need to be good at management, leadership, and authorship.

Developing skills in these three areas isn't always straightforward, but you can start small. The easiest way I know of is to begin asking these three questions. If you’re in a 1-on-1 meeting or even conducting your own self-reflection, ask the management question. If you’re in a weekly team meeting, ask the leadership question. If you’re meeting with a larger team or a key partner, ask the ecosystem question.

Beginning with honest feedback initiates a continuous improvement engine that leads to enhancement in our capabilities of management, leadership, and authorship.

In conclusion, whether we're discussing management, leadership, or authorship, it's clear that each plays a crucial role in achieving positive impact. From enhancing individual performance to influencing entire ecosystems, each area has its distinct but interrelated role. As leaders, our challenge and opportunity lie in understanding these nuances and developing our capabilities in all three areas. Remember, it's not about choosing between management, leadership, and authorship - it's about embracing all three to maximize our collective potential.

I'd love to hear your thoughts on these three aspects of leading - management, leadership, and authorship. How have you balanced these roles in your own leadership journey? What challenges have you faced? Feel free to share your experiences and insights in the comments below or reach out to me personally.

Photo by Aksham Abdul Gadhir on Unsplash

Maximizing Organizational Performance: 7 Key Questions

Making organizations better is hard, but it doesn’t have to be complicated.

Leaders are often charged with "making the organization perform better." That's an incredibly difficult mission unless we understand what an organization, especially ours, is and how it works. Only then can we diagnose organizational problems and make improvements.

This is a pretty long, nerdy post, so here's the tl;dr for those in a hurry, and for those who need a little taste to prove the read is worth it.

If you're trying to make an organization perform better, start by asking (just) seven questions. I think you'll make sense of your biggest problems pretty quickly:

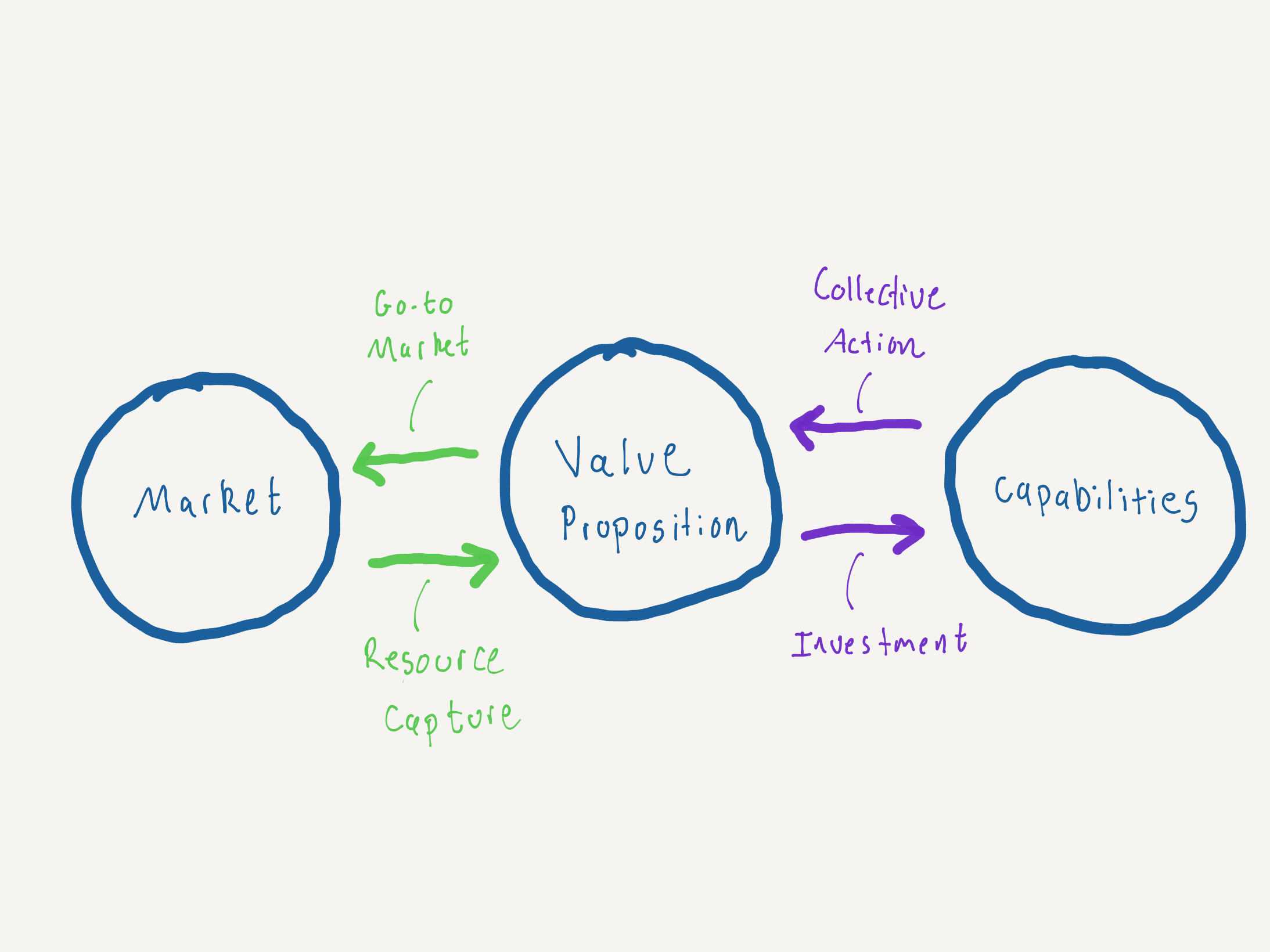

Value Proposition: What do we create that other people are willing to sacrifice something (i.e., pay) for?

Market: Who cares about what we have to offer?

Capabilities: What are the handful of things we really need to be good at to create something of value?

Go-to-Market Systems: How will we engage with our market?

Resource Capture Systems: How does the organization get the resources it needs?

Collective Action Systems: How will we work together to turn our capabilities into something of value?

Investment Systems: How will we develop the capabilities that matter most?

Making organizations better is hard, but it doesn't have to be complicated.

Leaders are often charged to “make the organization perform better”. That’s an incredibly difficult mission unless we understand what an organizations, especially ours, is and how it works. Only then can we diagnose organizational problems and make improvements.

This is a pretty long, nerdy, post so here’s the tl;dr for those in a hurry, and for those that need a little taste to prove the read is worth it.

If you’re trying to make understand and organization and help it perform better, start with asking (just) seven questions. I think you’ll make sense of your biggest problems pretty quickly:

Value Proposition: What do we create that other people are willing to sacrifice something (i.e., pay) for?

Market: Who cares about what we have to offer?

Capabilities: What are the handful of things we really need to be good at to create something of value?

Go-to-Market Systems: How will we engage with our market?

Resource Capture Systems: How does the organization get the resources it needs?

Collective Action Systems: How will we work together to turn our capabilities into something of value?

Investment Systems: How will fwe develop the capabilities that matter most?

Making organizations better is hard, but it doesn’t have to be complicated.

The Seven-Part Model of Organizations

So, what is an organization?

I'd propose that an organization, at its simplest, is only made up of seven components:

Value Proposition

Market

Capabilities

Go-to-Market Systems

Resource Capture Systems

Collective Action Systems

Investment Systems

If we can understand these seven things about an organization, we can understand how it works and consequently make it perform better. There are certainly other models and frameworks for understanding organizations (e.g., McKinsey 7-S, Business Model Canvas, Afuah Business Model Innovation Framework) which serve specific purposes - and I do like those.

This seven-part model of organizations is the best I've been able to produce which maintains simplicity while still having broad explanatory power for any organization, not just businesses. Each component of the model answers an important question that an organization leader should understand.

The seven parts (Detail)

The first three parts of the model are what I think of as the outputs - they're the core foundation of what an organization is: a Value Proposition, a Market, and a set of Capabilities.

Value Proposition: What do we create that other people are willing to sacrifice something (i.e., pay) for?

The Value Proposition is the core of an organization. What do they produce or achieve? What is the good or the service? What makes them unique and different relative to other alternatives? This is the bedrock from which everything else can be understood. Why? Because the Value Prop is where the internal and external view of the organization come together - it's where the rubber meets the road.

It's worth noting that every stakeholder of the organization has to be satisfied by the Value Proposition if they are to engage with the organization: customers, constituents, shareholders, funders, donors, employees, suppliers, communities, etc.

Market: Who cares about what we have to offer?

Understanding the Market is also core to an organization because any organization needs to find product-market fit to survive. This question really has two subcomponents to understand: who the people are and what job they need to be done or need that they have that they're willing to sacrifice for.

It's not just businesses that need to clearly understand their Markets - governments, non-profits, and even families need to understand their Market. Why? Because no organization has unlimited resources, and if the Value Proposition doesn't match the Market the organization is trying to serve, the organization won't be able to convince the Market to part with resources that the organization needs to survive - whether that's sales, time, donations, tax revenues, or in the case of a family, love and attention from family members.

Capabilities: What are the handful of things we really need to be good at to create something of value?

Thus far, we've talked about what business nerd types call "product-market fit," which really takes the view that the way to understand an organization is to look at how it relates to its external environment.

But there's also another school of thought that believes a firm is best understood from the inside out - which is where Capabilities come in.

Capabilities are the stuff that the organization has or is able to do which they need to be able to produce their Value Proposition. These could be things like intellectual property or knowledge, skills, brand equity, technologies, or information.

Of course, not all Capabilities are created equal. When I talk about Capabilities, I'm probably closer to what the legendary CK Prahalad describes as "core competence." Let's assume our organization is a shoe manufacturer. Some of the most important Capabilities probably are things like designing shoes, recruiting brand ambassadors, and manufacturing and shipping cheaply.

The shoe company probably also has to do things like buy pens and pencils - so sure, buying office supplies is a Capability of the firm, but it's not a core Capability to its Value Proposition of producing shoes. When I say "Capabilities," I'm talking about the "core" stuff that's essential for delivering the Value Proposition.

Finally, we can think of how Capabilities interact with the Value Proposition as an analog to product-market fit, let's call it "product-capability fit." Aligning the organization with its external environment is just as important as aligning it to its internal environment.

When all three core outputs - Value Proposition, Market, and Capabilities - are in sync, that's when an organization can really perform and do something quite special.

In addition to the three core outputs, Organizations also have systems to actually do things. These are the last four components of the model. I think of it like the four things that make up an organization's "operating system."

Go-to-Market Systems: How will we engage with our Market?

How an organization "goes to market" is a core part of how an organization operates. Because after all, if the product or service never meets the Market, no value can ever be exchanged. The Market never gets the value it needs, and the organization never gets the resources it needs. A good framework for this is the classic marketing framework called the 4Ps: Price, Product, Place, and Promotion.

But this part of the organization's "operating system" need not be derived from private sector practice. Governments, nonprofits, faith-based organizations, and others all have a system for engaging with their Market; they might just call it something like "service delivery model," "logic model," "engagement model," or something else similar.

The key to remember here is that go-to-market systems are not how parties within the organization work together; it's how the organization engages with its Market.

Resource Capture Systems: How will the organization get the resources it needs?

Just like a plant or an animal, organizations need resources to survive. But instead of things like food, sunlight, water, and oxygen, and carbon dioxide, organizations need things like money, materials, talent, user feedback, information, attention, and more.

So if you're an organizational leader, it's critical to understand what resources the organization needs most, and having a solid plan to get them. Maybe it's a sales process or levying of a tax. Maybe it's donations and fundraising. Maybe for resources like talent, it's employer branding or a culture that makes people want to work for the organization.

This list of examples isn't meant to be comprehensive, of course. The point is that organizations need lots of resources (not just money) and should have a solid plan for securing the most important resources they need.

Collective Action Systems: How will we work together to turn our capabilities into something of value?

Teamwork makes the dream work, right? I'd argue that's even an understatement. The third aspect of the organization's operating system is collective action.

This includes things like operations, organization structure, objective setting, project management approaches, and other common topics that fall into the realm of management, leadership, and "culture."

But I think it's more comprehensive than this - concepts like mission, purpose, and values, decision chartering, strategic communications, to name a few, are of growing importance and fall into the broad realm of collective action, too.

Why? Two reasons: 1) organizations need to move faster and therefore need people to make decisions without asking permission from their manager, and, 2) organizations increasingly have to work with an entire network of partners across many different platforms to produce their Value Proposition. These less-common aspects of an organization's collective action systems help especially with these challenges born of agility.

So all in all, it's essential to understand how an organization takes all its Capabilities and works as a collective to deliver its Value Proposition - and it's much deeper than just what's on an org chart or process map.

Investment Systems: How do we develop the capabilities that matter most?

It's obvious to say this, but the world changes. The Market changes. Expectations of talent change. Lots of things change, all the time. And as a result, our organizations need to adapt themselves to survive - again, just like Darwin's finches.

But what does that really mean? What it means more specifically is that over time the Capabilities an organization needs to deliver its Value Proposition to its Market changes over time. And as we all know, enhanced Capabilities don't grow on trees - it takes work and investment, of time, effort, money, and more.

That's where the final aspect of an organization's operating system comes in - the organization needs systems to figure out what Capabilities they need and then develop them. In a business, this could mean things like "capital allocation," "leadership development," "operations improvement," or "technology deployment."

But the need for Investment Systems applies broadly across the organizational world, too, not just companies.

As parents, for example, my wife and I realized that we needed to invest in our Capabilities to help our son, who was having a hard time with feelings and emotional control. We had never needed this "capability" before - our "market" had changed, and our Value Proposition as parents wasn't cutting it anymore.

So we read a ton of material from Dr. Becky and started working with a child and family-focused therapist. We put in the time and money to enhance our "capabilities" as a family organization - and it worked.

Again, because the world changes, all organizations need systems to invest in themselves to improve their capabilities.

My Pitch for Why This Matters

At the end of the day, most of us don't need or even want fancy frameworks. We want and need something that works.

I wanted to share this framework because this is what I'm starting to use as a practitioner - and it's helped me make sense of lots of organizations I've been involved with, from the company I work for to my family.

If you're someone - in any type of organization, large or small - I hope you find this very simple set of seven questions to help your organization perform better.

Making organizations better is hard, but it doesn't have to be complicated.

Preventing Trust-killers

A good way to assess an organization is by examining the types of problems the majority of their time on.

There are three general types of problems.

Type A problems are where the state of the art isn’t good enough. Even if we executed to the fullest extent of possible we’d still fall short. Cancer is like this. Even if the state of the art was applied with full fidelity, tons of people would suffer and die early deaths.

Type B problems are where the state of the art solutions would be good enough, but something’s not going to plan. Many operational problems are like this. We have a process, but life is messy so things go wrong even though the issue was “never supposed to happen.” So we fix the problem, improve our ability to execute, or both.

Type C problems are the ones caused by bad actors with nefarious intent. It’s the problem that arises because someone tries to screw over someone else, on purpose, because they can get away with it. It could be someone taking credit for a colleagues work, or a person running a Ponzi scheme which defrauded investors of billions of dollars. In a Type C problem, the bad actor knows what they are doing is wrong, unfair, or sub-optimal, but they do it anyway.

A good way to judge a team or enterprise is by looking at the proportion of time spent on each type of problem. Organizations that are well led and well managed tend to spend a lot of their time on Type A problems. They create systems and coach people well to minimize Type B problems, and they simply don’t tolerate Type C problems and the people that cause them.

Well run organizations and their leaders know that Type C problems are trust-killers which make working the more important Type A and Type B problems infinitely harder.

Luckily, creating safeguards to prevent Type C problems is not complicated. All it takes is the team or its leader articulating a set of values, behavioral norms, and performance standards that that make it clear how we’ll act and how we won’t. Then, the leader has to coach people up to those standards and remove people who continually violate them.

This may take courage, but it’s not complicated.

To me, thinking through the “how” of work, might be the most underrated activity in all of management and leadership. And it can be so easy - even talking for literally an hour with a team about “how are we going to act and how are we not going to act” can make a huge difference.

Photo Credit: Unsplash @quinoal

In-sourcing Purpose

At work, we shouldn’t depend on our companies to find purpose and meaning for us. We have the capability to find it for ourselves.

When it comes to being a husband and father, doing more than just the bare minimum is not difficult. At home, I want to do much more than mail it in.

The obvious reason is because I love my family. I care about them. I find joy in suffering which helps them to be healthy and happy. I believe that surplus is an essential ingredient to making an impactful contribution, and with my family I give up the surplus I have easily, perhaps even recklessly. I love them, after all.

Photo Credit: Unsplash @krisroller

And yet, love doesn’t explain this fully. The ease with which I put in effort at home taps into a deeper well of motivation and purpose.

With Robyn, our marriage is driven by a deeper purpose than having a healthy relationship, or perhaps even the commitment to honoring our vows. We find meaning in building something, in our case a marriage, that could last thousands of years or an eternity if there is a God that permits it. We’re trying to build something that could last until the end of time, until there is nothing of us that exists - in this world or beyond. We’re trying to make a marriage that’s more durable than “as long as we both shall live.” We find meaning in that.

Though we’ve never talked about it explicitly, I think we also find meaning in trying to have a marriage that’s based on equality and mutual respect. It’s as if we’re trying to be a beacon for what a truly equal marriage could look like. I don’t think we’ve succeeded in this yet; I’m certain that despite our best efforts, Robyn still bears an unequal portion of our domestic responsibilities. But yet, we try to find that elusive, perfectly equal, and mutually respectful marriage and we find meaning in that pursuit.

As a father, too, I find purpose and meaning that exeeceds the strong love and attachment I have with my children. I find it so inspiring to be part of something that spans generations and millennia. I am merely the latest steward to pass down the love, knowledge, and virtues of our ancestors. I find it humbling to be part of a lineage that started many centuries ago, and that will hopefully exist for many centuries in the future. Being one, single, link in this longer chain moves me, deeply.

I also believe deeply in a contribution to the broader community, to human society itself. And there too, fatherhood intersects. Part of my responsibility to humanity, I believe, is to raise children that are a net force for goodness - children that because of their actions make the world feel more trustworthy and vibrant. Through my own purification as a father, I can pass a purer set of values and integrity to our children, and accelerate - ever so slightly - the rate at which the arc of humanity and history bends towards justice. This is so lofty and so abstract, but yet, I find meaning in this.

These sources of deep purpose make it easy, trivial even, to put forth an amount of energy toward being a husband and father that a 16 year old me would find incomprehensible.

Finding this deep and durable source of purpose has been harder in my career, though I’m realizing it might have been hidden in plain sight all along.

I often felt maligned when I worked at Deloitte, especially when it felt like the ultimate end product of my time was simply making wealthy partners wealthier. At least Deloitte was a culture of kind people, and also had a sincere commitment to the community - I found some meaning in that.

But in retrospect, I think I missed the point. Deloitte, after all, is a huge consultancy. Its clients are some of the largest and most influential enterprises in the history of the world. Deloitte also produces research that is read by leaders and managers across the world. The amount of lives affected by Deloitte, through its clients, is probably in the billions. While I was there, I had an opportunity - albeit a small one - to affect the managerial quality of the world’s largest companies. That is incredibly meaningful. In retrospect, I wish I would’ve remembered that when I was toiling away on client projects, wishing I was doing anything else to earn a living.

While working in City government, sources of purpose and meaning were easier to find. It was easy to give tremendous effort, for example, toward reducing murders and shootings. I was a civilian appointee, and relatively junior at that - but we were still saving lives, literally. But even beyond that, I found meaning in something more humble - I had the honor and privilege of serving my neighbors. That phrase, serving my neighbors, still wells my eyes up in tears. What a gift it was to serve.

And now, I work in a publicly traded company. We manufacture and sell furniture. These are not prima facie sources of deep meaning and purpose. In the day-to-day, week-to-week, grind I often find myself in the same mindset as I was at Deloitte, asking myself questions like, why am I here, or, am I wasting my time?

And yet, I also realize that with hindsight I would probably realize that meaning and foundation on which to assemble a strong sense of purpose was always there, had I cared enough to look for it.

Why, I have been thinking this week, is it so easy to to find meaning purpose at home, but so difficult at work? There must be a deep well of meaning from which to draw, hidden in plain sight, why can’t I find it?

At home, I realized, we are free. We have nobody ruling us, but us. We are free to explore and think and make our family life what we wish it to be. I think and talk openly with Robyn about our lives. We reflect and grapple with our lived experiences and take it upon ourselves to make meaning from it. We aren’t waiting for anyone else to tell us what our purpose as partners, parents, or citizens.

In a way, at home, we in-source our deliberations of purpose. We literally do it “in house”. We know it is is on us to make meaning of our marriage and our roles as parents, so Robyn and I do it. We have, in effect in-source our search for meaning and purpose.

At work, I have done the opposite.

In my career, I have outsourced my search for meaning and purpose. I’ve waited, without realizing it, for senior executives to tell me why what we’re doing matters. I’ve whined, in my head at least, when the mission statements and visions of companies I’ve worked for - either as an employee or as a consultant - have been vacuous or sterile.

In retrospect, I’ve freely relinquished my agency to create meaning and purpose to the enterprises for which I have worked. What a terrible mistake that was. Why was I waiting for someone else to find purpose for me, when I could’ve been creating it for myself all along?

When companies do articulate statements of purpose well, it is powerful and I appreciate it. My current company has a purpose statement, for example, and it does resonate with me. I’m glad we have one.

But yet, that’s not enough. To really give a tremendous amount of discretionary effort at work, I need to believe in something much more specific to me. After all, even the best statement of purpose put out by a company is, by design, something meant to appeal to tens of thousands of people. I shouldn’t expect a corporate purpose statement to ignite my inspiration, such an expectation is not reasonable or fair. No company will ever write a purpose statement that’s specifically for me, nor should they.

Rather than outsource my search for meaning and purpose, I’ve realized I need to in-source it. Perhaps with questions like these:

What makes my job and working as part of this enterprise special? What’s something about it that’s so valuable and important that I want to put my own ego, career development, and desire to be promoted aside and contribute to the team’s goal? What can I find meaning in and be proud of? What about being here makes me want to put effort in beyond the bare minimum?

Like I said, I work for a furniture company - certainly not something glamorous or externally validated . And yet, there can be so much meaning and purpose in it, if I choose to see it.

We are in people’s homes and we have this ability to rehabilitate people’s bodies and minds. We create something that brings comfort to other people and for every family movie night and birthday party - the biggest and smallest moments in the lives of our customers and their families, we are there. That’s worth putting in a little extra for.

And we’re a Michigan company, headquartered in a relatively small town. I get to be part of a team bringing wealth, prosperity, and respect to our State. I can’t tolerate it when people from elsewhere in the country snub their noses at Michigan, calling us a “fly over” state. I find meaning in that competition to be an outstanding enterprise - why not have the industry leader in furniture manufacturing and retailing be a Michigan company?

Without even considering the meaning and joy I find in creating high-performing teams that unleash people’s talent, there is so much meaning and purpose that’s hidden in plain sight - even at a furniture company. But that meaning is nearly impossible to find unless we stop being dependent on others to create meaning for us - we have to bring the search for purpose back in house.

How interesting might it be if everyone on the team created their own purpose statement, rather than depending on the enterprise to provide one for them? What if companies helped their employees create their own purpose statement instead of making one for them? I think such an approach would be interesting and, no pun intended, meaningful.

Organizations are energy processes

Can you imagine what organizations would be like if there was so much human energy created that it was “too cheap to meter”? None of the world’s problems would be out of reach. Not one.

When I have an organizational problem - like an underperforming team, or an organization that seems like it’s stuck - I just want a mental model to help me figure it out that is practical and simple to use. As a practitioner, what I care about is having something that works.

I found inspiration after reading a Works in Progress article about making energy too cheap to meter: organizations are energy processes which create, harness, and apply human energy. To solve organizational problems, all we need to do is improve how the organization creates and applies energy.

Photo Credit: Unsplash @pavement_special

When I say “energy processes”, I mean something like what I’ve outlined below. Take nuclear fission as an example. The end to end process for creating and applying nuclear energy happens in four steps:

Accumulate a fuel source (uranium) from which energy can be created

Create energy from the fuel source (i.e., using a nuclear reactor)

Harness and transmit the energy (create electricity via a steam turbine and deliver it to a plug in someone’s home)

Apply it to something of value (the electricity goes into a lamp which someone uses to read a favorite book after sunset)

Organizations, similarly, are an energy process:

The fuel that powers organizations are people and the ideas, information, expertise, and the motivation they bring to the table (i.e., like the uranium)

Organizations try to get their people to put forth effort that can be used to create something of value (i.e., like the nuclear reactor).

Organizations then create systems to harness the efforts of their people and channel it into collective goals (i.e., like the steam turbine and power lines)

The organization tries to ensure all the energy they’ve created goes into something that the end customer actually cares about, which they can be compensated for (i.e., like the reading lamp used to read a novel)

Thinking of organizations as energy processes can help us understand organizational challenges quickly and simply. When I have an organizational problem I can quickly ask myself these four questions, and determine where my organization’s issues lie:

Do we have enough “fuel” to create energy?

How much energy are we creating?

How much energy are we harnessing?

Are we applying our energy to something of value?

You can be the judge of whether this mental model is simple and useful. The rest of this post gives some detail on how to actually use the energy process model to diagnose an organizational problem.

Question 1: Do we have enough “fuel” to create energy?

One of my favorite questions to ask a teammate is: what percent of your potential impact do you feel like you are actually making? In my experience, most people are not even close to fully applying their skills, talents and ideas. A tremendous amount of potential is wasted in organizations.

To get a sense of whether there’s sufficient “fuel” in your organization or the degree to which potential is wasted, look for the following:

Complaints - if people are complaining, it means they have energy they’re not using and care enough to say something.

Regrettable losses - if people are leaving your company and getting good jobs and promotional opportunities elsewhere, at least one other organization seems something that you do not

Ask the team - people care about whether they’re wasting their time and energy. If you ask them, they’ll tell you if they have talents and energy that are being wasted

Ask yourself this question: if I assumed the people around me had talent, potential, and cared, would I be acting differently? If you answer that question with a “yes” it probably means you have more potential around you than you realize.

In my experience, it is almost never the case that an organization lacks sufficient “fuel” to create energy. Don’t shift the blame to the people around you, look inward first.

Question 2: How much energy are we creating?

I loved The Last Dance, the ESPN Films miniseries the 1997-1998 NBA Champion Chicago Bulls. It was remarkable to me how that team seemed to try so hard, and how Michael Jordan was able to be a catalyst, pulling tremendous amounts of energy from his teammates. Watching the documentary, the energy being created was obvious.

To get a sense of whether your organization is creating energy, look for the following::

Body language and non-verbals - If you work in an office, walk the floor and observe people through the windows of conference rooms, so you can’t hear what people are saying - just observe with your eyes. Do people seem like they want to be there or are trying very hard? Do they look bored? It’s pretty easy to see the parts of your organization that have energy just by being a fly on the wall and paying attention.

Experiments - When people are trying new things - whether its practices, sharing new ideas, or under the radar projects that nobody has asked for - it’s a good indication that energy is being created. It doesn’t have to be a grand novelty. I just had a colleague the other day, our team’s agile scrum master, that tried out a new framework for debriefing our bi-weekly sprint of work. He literally changed our four usual questions to four new questions. He just did it. I immediately thought, “our team has some energy and psychological safety if our scrum master is trying new things - this is awesome.”

Spontaneous Fun - I love to see teams that celebrate birthdays, bring snacks to work, create trivia games, or play pranks on each other. These are examples of activities that take energy that don’t have to occur to get the job done, they’re just for fun. If people are spending time putting energy toward having fun at work, it probably means they have plenty of energy for the work itself

Engagement Scores - Again, there are lots of survey companies that can help your organization execute a simple engagement survey. The ball don’t lie, and you can track engagement over time. If you have high engagement it probably means your organization is creating a lot of energy..

Question 3: How much energy are we harnessing?

One of my favorite bits of comedy is the Abbott and Costello, “Who’s on first?” skit. Nobody has any idea what’s going on and they have a pointless conversation with no conclusion. It’s hilarious to watch, and an excellent illustration of what it feels like when there’s lots of energy around but it’s not being channeled and applied.

To get a sense of whether your organization is effectively harnessing and applying energy, look for the following:

Low value work - In a factory setting, it can be easy to spot waste. In corporate offices, it’s harder to spot or prove inefficiency. Low value work is a good tell. If people don’t have anything better to do than low-value, non-impactful, work it probably means your organization isn’t harnessing energy well because it’s going into something that’s not worthwhile. When people have the opportunity to do something more impactful, they tend to.