Team 144

I’ve never wanted a Michigan Football team to win more than this one.

““No man is more important than the team.

No coach is more important than the team.

The Team. The Team. The Team””

One of the strongest convictions I have is the value, beauty, and honor it is to be part of a great team.

It’s in my DNA, probably because as an only child I have desperately wanted to be part of something bigger than myself for my whole life. And, as an alumnus of the University of Michigan, the value of “The Team” is part of my identity, because of Coach Bo Schembechler’s legendary speech which I’ve linked above.

On Monday, January 8, the 144th edition of the University of Michigan football team will take the field to compete for a national championship. I have never wanted a Michigan team to win as badly as this one.

For me though, it’s less about football and the cachet that comes from being an alumnus of a team that wins “the natty.” I have admired this team from the very start because they are winning AS A TEAM and embody the spirit of an elite team, through and through.

One of the Detroit Police Department leaders I looked up to most had this on her team’s work area whiteboard, in perpetuity: “You get a lot more done when you don’t care who gets the credit.”

That, to me, is the simplest way of describing what a truly great team believes. It’s the same ethos that Coach Bo describes in “The Team Speech”. A truly great team cares more about the mission, the cause, the person they are serving, and the team’s goal more than individual accolades. That spirit is what has I’ve seen in Team 144 and been inspired by this whole season.

Here are just some of the examples that have stuck out to me that show this spirit in Team 144:

Coach Harbaugh is constantly deflecting attention in post game interviews and quickly getting off camera. Instead, he says to the field reporter, “you should talk to this man right here” and gracefully exists before his player takes the mic.

In the Ohio State game, All-American Offensive Lineman Zak Zinter went down with an injury late in the game, at a critical moment. On the very next play Blake Corum ran in a touchdown. The first thing he does? Go up directly to the sideline camera and throw up his teammate’s number with his hands, dedicating the TD to their injured teammate, on behalf of the entire squad.

Apparently this week, Coach Harbaugh asked JJ McCarthy (QB1) if he wanted to talk about this future (i.e., his NFL prospects). McCarthy basically gives him a “naw, I’m good coach.” Basically saying instead that he’s focused on the national championship game and they can talk about his future after the CFP championship.

In the CFP Semifinal, Michigan (with 2 five star recruits on its roster) beat Alabama (with 18 five star recruits on its roster). That doesn’t happen unless coaches develop players up and down the depth chart and unless everybody participates and steps up to play their best as a single unit.

There was clearly a culture change after the Covid season. This team openly talks about how much they love each other and how they play for each other and play for Michigan. In any post game interview I’ve seen, the reporters don’t seem like they can get someone to talk about themselves instead of the team.

After each huge win, I love seeing Blake Corum’s expression. He and other top players constantly talk about the team’s goal. And Corum’s words and expression sum up the same thing, “Job’s not done.” This is huge on a football team to have one of your best players and team leaders focused on the team’s goal immediately after a big win. It sends a huge message on what’s important to the entire locker room.

After all the drama of the season, you didn’t hear any fingerpointing coming out of the locker room. All we saw was unity, and all we heard was the same message, we’re a team and we’re focused on our goals. No matter what was swirling in the press and no matter who the head coach was for that week, you heard no dissent in the ranks. Not once.

Several of the team’s key players decided to return for another season because they had “unfinished business” and wanted to win a championship. Moreover, after last year’s loss to TCU in the CFP semifinal, JJ McCarthy said, “But we’ll be back, and I promise that.” And here we are.

To be sure, there are more examples than what I’ve listed. These are just some of my favorites. The punchline is this: Team 144 embodies what it means to be a team.

—

Sometimes, I get really frustrated with life at work. So often, I worry that someone is going to put themselves ahead of the team. I’ve experienced it personally, and it happens a lot: People hide information so they can maneuver. They try to claim credit for the team’s work behind the scenes. They throw you under the bus, baselessly, to the boss. They don’t give others opportunities to lead because they want to earn their gold star or be top of mind for a promotion.

To be clear, all this is bullshit and wrong. To be sure, I’m not perfect (I’m sure I’ve behaved selfishly) but I honestly try everyday to be a team player and not a selfish agent. And, very little makes me angrier or sadder than when people screw the team to advance their individual interests. It offends me to my core, and makes me feel hopeless that true, pure teamership is possible.

But Team 144 gives me hope.

The fact there’s a team out there playing elite college football and competing for the sport’s highest championship gives me hope. This year, there’s at least one elite team, in it’s truest and purest sense - that’s out there in the world doing it right. Team 144 has reminded me that it’s still possible - even in a culture that often seems defined by self-absorption and self-centeredness - to have a great team. The idea of a team - that acts as one unit and achieves a mission greater than it’s individual members - still lives.

So to Team 144, thank you. Thank you for a great season. Thank you for giving us alumni something to get excited about and reconnect over. But most of all, Team 144, this wolverine thanks you for reminding us what Coach Bo meant when he proclaimed, “The Team. The Team. The Team.”

Go get that natty tomorrow, and forever Go Blue. We’ll be rooting hard for you from Detroit.

How to build a Superteam

Superteams don’t just achieve hard goals, they elevate the performance of teams they collaborate with.

In today's dynamic business landscape, the concept of building high-performing teams and managing change has been extensively discussed in management and organization courses.

However, as I've gained real-world experience, I've come to realize that the messy reality we face as leaders is far different from the pristine case studies we encountered in school. Collaborating with other teams, even within high-performing organizations, presents unique challenges that demand a fresh perspective.

The Dilemma of Collaboration for High-Performing Teams

As high-performing teams, we often find ourselves operating within larger enterprises, requiring collaboration with teams from other departments and divisions. However, the reality is that not all these teams are high-performing themselves, which poses a significant challenge. Most enterprises lack the luxury of elite talent, and even the most high-performing teams can burn out if burdened with carrying the weight of others.

Over time, organizations tend to regress to the mean, losing their edge and succumbing to stagnation. If we truly aspire to change our companies, communities, markets, or even the world, simply building high-performing teams is not enough. We must contemplate the purpose of a team more broadly and ambitiously.

What we need are Superteams.

As I define it, a Superteam meets two criteria:

A Superteam is a high-performing team that's able to achieve difficult, aspirational goals.

A Superteam elevates the performance of other teams in their ecosystem (e.g., their enterprise, their community, their industry, etc.).

To be clear, I mean this stringently. Superteams not only fulfill their own objectives and deliver what they signed up for but also export their culture. Through doing their work, Superteams create a halo that elevates the performances of the people and partners they collaborate with. They don't regress to the mean; they raise the mean. Superteams, in essence, create a feedback loop of positive culture that is essential to make change at the scale of entire ecosystems.

One way to think of this is the difference between a race to the bottom and a race to the top. In a race to the bottom, the lowest-performing teams in an ecosystem become the bottlenecks. Without intervention, these low-performing teams repeatedly impede progress, wearing down even high-performing teams. Eventually, the enterprise performs to the level of that sclerotic department. This is the norm, the race to the bottom where organizations get stale and regress to the mean.

Superteams change this dynamic. They export their culture to those low-performing teams that are usually the bottlenecks in the organization, making them slightly better. This improvement gets, reinforced, and creates a transformative, positive feedback loop. As other teams achieve more, confidence in the lower-performing department grows. This is the race to the top, where raising the mean becomes possible.

The biggest beneficiary of this feedback loop, however, is not the lower-performing team—it's actually the Superteam itself. Once they elevate the teams around them, Superteams can push the boundaries even further, reinvesting their efforts in pushing the bar higher. This constant pushing of the boundary raises the mean for everyone, ultimately changing the ecosystem and the world.

How to Build a Superteam

The first step to building a Superteam is to establish a high-performing team that consistently achieves its goals. Moreover, a Superteam cannot have a toxic culture since it is difficult, unsustainable, and dangerous to export such a culture.

Scholars such as Adam Grant, who emphasizes the importance of fostering a culture of collaboration, have extensively studied how to build high-performing teams with positive cultures. Drawing from their work, particularly in positive organizational scholarship, we can further expand our understanding of Superteams.

In addition to the exceptional work of these scholars, it is essential to focus on the second criterion for a Superteam: elevating the performance of other teams in the ecosystem. How can a team work in a way that raises the performance of others they collaborate with? To achieve this, I propose four behaviors that make a significant difference.

First, a Superteam must act with positive deviance. Superteams should feel materially different from average teams in its ecosystem. Whether in composition, meeting structures, celebration of success, language, or bringing energy and fun, Superteams challenge conventions. Such explicit differences not only generate above-average results but also create a safe space for others to act differently.

Second, a Superteam must be self-reflective and constantly strive to understand and improve how it works. Holding retrospectives, conducting after-action reviews, or relentlessly measuring results and gathering customer feedback allows Superteams to make adjustments and changes with agility. This understanding of internal mechanics and the ability to transmit tacit knowledge of the culture enable every team member to become an exporter of the Superteam's culture.

Third, a Superteam walks the line between open and closed, maintaining a semi-permeable boundary. While being open and transparent is crucial for exporting the team's culture, maintaining a strong boundary is equally important. Being overly collaborative or influenced by the prevailing culture can hinder positive deviance. Striking the right balance allows Superteams to create space for exporting their culture while protecting it from easy corruption.

Finally, a Superteam must act with uncommon humility and orientation to purpose. By embracing the belief that "you can accomplish a lot more when you don't care who gets the credit," Superteams prioritize the greater purpose of raising the mean instead of seeking personal recognition. This humility allows them to make cultural improvements without expecting individual accolades, empowering others to adopt and embrace the exported culture.

Over the years, I've become skeptical of mere "culture change initiatives." True culture change requires more than rah-rah speeches and company-wide emails. Culture change demands role modeling and the deliberate cultivation of Superteams. Any team within an ecosystem can change its culture and aspire to build Superteams that export their culture, ultimately transforming the world around them for the better.

We can learn to be lucky

Even the best teams and organizations I’ve been part of underperform their potential. We can and should learn from failures. But we can learn just as much from successes with the right questions and approach.

Learning only when we make a mistake is not enough.

Life is too hard. Creating value in enterprises is too hard. Marriage is too hard. Reaching goals and making our dreams come true is too hard. All these aspirations are too hard to only learn some of the time.

Some people say we learn more from failures than from successes, and that may or not be true. But the way I see it, that’s a misleading trade off: we can learn a lot from both.

However, what I’ve observed in organizations is that in practice teams usually learn much less from successes than from failures. It’s not that they can’t learn more, they just don’t.

This is for two main reasons. First, teams usually have less motivation to learn from success - why be a downer and interrogate our victory when we could be celebrating? Even when teams choose to debrief successes, they seem less willing to be introspective and self-critical so the debriefs they do are less fruitful. Moreover, most organizations have more systems that force debriefs of mistakes to happen.

The second reason why teams tend to learn less from success is a matter of technique. Learning from failure is a bit more familiar because it’s an exercise of cause and effect. We saw bad effects, and the goal of a debrief is to understand the root causes. By understanding the root causes we can make different choices in the future.

Learning from success is different (and perhaps harder) because it’s an exercise of understanding counterfactuals. What could we have done to obtain a better result? What aspects of our success were because of our decisions and skills, rather than good circumstances? The fundamental questions when trying learn from a success are different than those needed to debrief a failure.

When you’re doing your next debrief, try these three questions to get the most learning possible out of a success. I’ve included some rationale for the questions and some examples within each.

Question 1: What would’ve had to be true to have a 2x better result? What about a 5x or 10x better result?

This question helps us understand the money we left on the table. If we were successful it means we already had some level of competence or skill related to the challenge at hand. Could we have done better? Why didn’t we? Are we at a plateau of performance? How can we break the plateau and get to the next level? This is what this question gets at.

I thought about this question a lot when working on violence prevention programs at the Detroit Police Department. There were quarters and years where we had substantial drops in shootings and murders. A lot of time that was because the community-based gang violence prevention programs we launched were working. But in Detroit, even after those successes, violence wasn’t at an acceptable level for our team, our leadership, or our community.

When we asked questions like, “why can’t have a 30% drop instead of 10% drop” we thought about other avenues for reducing violence. We started to explore domestic violence prevention, partnerships with social service organizations and faith-based organizations, and other non-traditional avenues. Thinking critically about our success helped us to lean in harder to the problem.

Question 2: What was a near-miss? What almost was a big problem but we got lucky?

This question helps us understand where caught a break. Teams generally discount their own luck, and do so at their own peril. Because the next time around, we might not be so lucky.

I just experienced this at Thanksgiving. Our family’s tradition is to go to the Detroit Lions’ Thanksgiving Day football game, and we host an early brunch at our house since we live closest to Downtown Detroit where the stadium is. I make bagels & lox, a breakfast casserole, and coffee. My father-in-law makes bloody marys.

When he arrived, he asked, “do you have ice?”

We usually do not have ice in our house. Our refrigerator is old, and doesn’t have a built-in ice machine. But this Thanksgiving, we were lucky - we happened to have extra ice in the freezer from a party we hosted a few weeks earlier.

Even though our family brunch was a resounding success, I learned something important: make ice part of the plan for any party. I added “get ice” to the party prep checklist I keep on my phone. I also plan to look into a better set of ice molds to make it easier to have ice on hand all the time.

Question 3: What gifts were just handed to us that we did nothing to earn?

This question helps to understand and shape luck. Teams usually have some headwinds or beneficial circumstances that just fall into their lap without even trying. Usually, those headwinds aren’t a guarantee for future challenges. But if we understand what made us lucky this time around, we can actively try to shape those headwinds in the future.

I saw this happen on a project some of my colleagues recently completed. It was a data analysis to understand a large area of SG&A for our company. The project was a clear success because the insights uncovered will have a huge benefit for our company and our customer. By all accounts the team did a great job and they executed flawlessly.

But they did have a healthy amount of luck, too. The executive sponsoring the project had an incredibly clear and specific question they wanted to understand. The clarity the team received up-front led to a very focused analysis on a specific set of data. Many times people who request work of analytical teams have no idea what they actually want to understand, and that creates huge drag on an analytics team.

It was a big headwind to have a clear, and focused question from jump. That’s definitely not a given on any project. But what we learned is that in the future we can push for clarity and actively shape the question very early in any analytics project to create headwinds for the team. We can shape our own luck.

—

Every team and every organization I’ve been part of underperforms. Even the best teams out there have even higher ceilings. We can and should learn from failures, but we can learn just as much from successes with the right questions and approach. And if we do that, we can learn to be better and contribute more to our teams, our customers, and our communities.

Photo credit: Unsplash @glambeau

Good Managers Produce Exceptional Teams

This is an OKR-based model to define what a good manager actually produces. It’s hard to be good at something without beginning with the end in mind, after all.

The difference between a good manager and a bad one can be huge.

Good managers make careers while others break them. Good managers bring new innovations to customers while others quit. Good managers find a way to make a profit without polluting, exploiting, or cheating while others cut corners. Good managers find ways to adapt their organizations while others in the industry go extinct.

But it’s almost impossible to be good at something without defining what success looks like. As the saying goes, “begin with the end in mind.”

This is one model for the results a good manager takes responsibility to produce.

What would you add, subtract, or revise? My hope is that by sharing, all of us that are committed to being good managers get better faster.

Objective: Be a Good Manager

Key Results:

Talent of each team member is fully utilized

Develop team members enough to be promoted

Team has and utilizes diverse perspectives

Team delivers measurable results on an important business objective

Team is trusted by internal and external customers

Team and all stakeholders are clear on on the why, what, how, when, and intended result of our work

Whole team feels supported and respected

Team stewards resources (time, money, etc.) effectively

To build a great team, get specific

To scale impact, every team leader has to build their team. Building a team is hard, but it’s not complicated.

To set us up for success, they key thing to do is get specific about the role, and the top 2-3 things we can’t compromise on in a candidate.

Building a team is hard, but it doesn’t have to be complicated.

What I’ve learned when trying to build teams (whether serving on hiring committees, recruiting fraternity pledges, or volunteer board members) is that most of the time we’re not specific enough.

To build a great team, we can’t just fill the role with a body. We can’t count on the perfect candidate either - there are no unicorns. Instead, we should be clear about the role, and the attributes that we can and cannot compromise on.

Here’s a video with a tool / mental model on how to actually do that.

How to take more responsibility

If leadership is essentially an act of taking responsibility, how do we create teams where more people take responsibility?

“I’ll take responsibility for that.”

Hearing this phrase in a team setting is generally a good sign. Choosing to be responsible for something is effectively an act of leadership. And whether it’s in our families, at work, at church, or in community groups, more people choosing to lead is a good thing.

So instead of worrying about abstract concepts like “leadership development”, why not just focus on “taking responsibility”? If more folks - like us and our peers - are taking responsibility for their conduct and the needs of others, isn’t that exactly what we want?

One way to foster responsibility-taking is to make it clearer why taking responsibility is really important. This is fairly intuitive, it’s hard to convince someone to take responsibility for something if they believe it doesn’t matter. In my experience, people on teams don’t take responsibility if the challenge is unimportant, myself included.

Another way to foster more responsibility-taking is to build up competence. This is also intuitive, if someone feels like they’re definitely going to fail or have no idea what they’re doing, they don’t step up to take responsibility. For example, if someone asked me to take responsibility for making sure a car’s design was safe, I would say absolutely not. I do believe having safe automobiles is extremely important, but I am not comfortable taking responsibility for something in which I have no competence.

A third way to foster more responsibility-taking is to make teams non-toxic. I’d put it this way. Let’s say you’re in a meeting about a new problem that’s come up, maybe it’s a product safety recall your company has to do. You’re deciding whether or not to step up and take responsibility for executing the recall effort.

If you believed everyone would dump every last problem on you and vanish, would it make you more or less likely to step up? If you weren’t sure whether your boss would constantly overrule your decisions or if it seemed like your colleagues would scrutinize your work unfairly, would you volunteer? If you questioned whether or not you’d get the money and staff to solve the problem, or felt like you’d get all the blame for a mistake and no gratitude for a success, wouldn’t you think twice about taking responsibility?

I would, regardless of how important it was or how competent I felt. If the culture around us is toxic, we shouldn’t expect to see responsibility-taking.

In the American context, we tend to emphasize competence a lot. We like “all-stars” and “high-potentials” to save the day. There is a danger, however, to overindexing on this when assessing leadership. Competence (and also confidence) is easy to fake. It’s also easy to have hubris and think we have more competence than we really do.

I would also hypothesize there are diminishing marginal returns to competence. After a certain point, adding more competence doesn’t lead to more responsibility taking if importance isn’t clear or if a team has a toxic environment. If we want to increase responsibility-taking, competence matters, but it’s not the only thing that matters.

The big realization from this thought experiment came when I put these ideas into the context of our family.

I, like many others, want my kids to take responsibility for their actions and for helping others as they grow older. In fact, I believe that I owe it to them to help them learn how to do take responsibility. But no extra-curricular activity, or online video is going to do that for me. I cannot expect our kids’ school to teach them to take responsibility.

Rather, the responsibility lies with me. I have to explain to them why taking responsibility for something, like befriending a classmate who is struggling with a bully, is important. I have to create a non-toxic environment at home, and let them make decisions for themselves. I have to give them the time and support, and help them clean up a mess when they screw up - even if I knew beforehand that whatever they were doing was going to fail.

Sure, maybe at the margins, some sort of class, extra-curricular, or book is going to help them build up fundamental competence in some way, like say in how to run a meeting or how to manage the budget of their lemonade stand. But even then, I’ll still have to coach them - they won’t learn everything from a class, video, or book.

In a family setting, it seems to me that learning to take responsibility has much more to do with how we interact with our kids and shape our family’s culture than it does with sending them away to camp for a few weeks and assuming the “training” they receive there will be enough.

So why do we think “leadership training” at work would have different results? It seems to me that if we really want to create teams where more and more people take responsibility, having “leadership development” retreats or “high-potential talent pipelines” are a bit of a sideshow.

What we should be doing is telling stories about why the work we do is important. What we should be doing is finding really specific training courses to build up contextually-specific competence. What we should be doing is treating our colleagues with more compassion so they can count on a reasonable level of support and respect when they step up and take responsibility for a challenge.

I’m skeptical of the concept of “leadership” and have been for a long time. It seems to me that if I want other around me to take on more responsibility - whether it’s my family, my neighbors, or my colleagues - the biggest obstacle to that is not them and their “leadership abilities” or creating more “leadership development” opportunities. The biggest obstacle is probably me, and the way I treat them.

The mindset which underlies enduring marriages

For our marriages to survive and thrive - whether to our soulmate or not - we have to believe that life is better done together, not solo. No amount of love, destiny, resources, compatibility, or compromise can make up for not having this pre-requisite shift in mindset.

If our lives can be explained by the treasurers we adventure to find, one of my few holy grails is understanding how to be a soulmate. I search, everywhere I can, for little bits of the wisdom that can help Robyn have a marriage that endures for our whole life and for anything that exists after.

My perspective on marriage and soulmates has evolved, to something like this:

We start our lives with a paintbrush in our hands, and a blank canvas. And we start to wonder - what’s the most beautiful picture I can put on this canvas? What is the life I want to live? As we grow up we experiment a bit as we learn to paint.

Eventually, we get a pretty good idea of the most beautiful life we can paint on the canvas, and we go after it. We start to paint more feverishly as we hit our teens and twenties.

If we’re lucky, along the way we fall in love with someone. If we’re really lucky, we take a leap and marry them. And then the dynamic at the canvas changes.

A wedding, I think, is the moment two people start to paint onto one canvas. But here’s the the trick: the moment we say I do, we suddenly have to figure out how to paint while both holding the same brush.

And suddenly, were not only painting, we’re both trying to prevent the brush we’re both holding - our marriage - from breaking. It seems like there are three ways to survive this.

First, we could strengthen our brush and make it more resilient. In a marriage, there are times when each person is pulling in a different direction, and the brush has to be strong and resilient so it does not break. This strategy represents the body of advice people give about integrity, being faithful, committing to better/worse/richer/poorer/sickness/health, having a thick skin, continuing to date, rekindling love and romance, etc.

Second, we could learn to compromise. Maybe sometimes we paint the way I want to paint. Other times, we paint the way you want to paint. We never pull in different directions at the same time. By compromising, we put less tension on the brush. By putting less tension on the brush, it does not break as readily. This strategy represents the body of advice people give about conflict resolution and compromise.

Third, we could both imagine the painting we want to put on the canvas the same way in our heads. What do we want our lives to be like? What’s the beautiful picture we want to paint together? By having a shared vision for what we want our marriage and life to be, we don’t put stress on the brush because both our hands are moving in the same direction. This strategy represents the body of advice people give about shared values, shared vision, and growing together instead of apart.

Truthfully, every married couple needs to be good at all three of these approaches. Moreover, the first strategy of having a strong and resilient brush seems like a given. I don’t know how any marriage survives without that.

What struck me is that compromising seems to be the least optimal strategy here. Sure, every married couple has to compromise at some point and compromise a lot. Robyn and I compromise, too.

But how terrible would it be to have a lifetime full only of compromise? Either you are settling for the average your whole lives, and the painting you produce is the average, path of least resistance. Or, one person dominates, and one person gets the painting they think is beautiful and the other has lived someone else’s dream.

Compromise is necessary, but it seems best as a last resort. What seems much better is to just be on the same page about life together - and wanting to paint the same painting, constantly evolving with each brushstroke as life unfolds.

This metaphor reminds me of a fundamental tension within management. Teams - whether it’s at work, in sports, in government, or in community - fall apart if people care more about themselves than what the team is trying to accomplish together. So to in marriage.

If I care more about what I want life to look like than I care about painting our shared vision for the canvas, and painting it together our marriage will suffer. This is no different than any team - a team only endures if its members sacrifice to advance the aspirations of the team and evolve as the team evolves.

When I first began to think about soulmates, I thought it was a question of predestination. There was a soul out there, and through God’s will I was linked to that soul. All I had to do was find her. We’d fall in love. We’d work through problems. We’d put in the work for a great marriage, and after we departed this world we’d be committed to anything that came after.

And I did, thank God, find her. But my perspective on soulmates and marriage is different now. I don’t think that it’s only about this compromise, loving each other, keeping on dating, and putting in the work stuff anymore.

To be clear, I do still believe all those things - love, compromise, romance, and commitment - are required to be married and probably to be soulmates.

But because of my own experience being married and learning vicariously from hundreds of other couples, I now believe that there’s a key prerequisite to marriage and even being soulmates. It’s a mindset and orientation toward life that believes together is better.

We can’t just keep painting the canvas we started with prior to being married. We also can’t just find someone compatible, that we love and try to stitch our separate canvases together. We can’t even create a fully detailed blueprint for the canvas of our life and marriage, agree to it prior to a wedding, and never evolve it - life’s unpredictability certainly doesn’t permit that.

Instead, deep down, we have to fundamentally believe that the enterprise of painting a shared canvas, with a shared vision, using the same brush is what a beautiful life is. The critical prerequisite for marriage is that our mindset shifts from believing that the best way to live is being a solo artist, versus being part of a creative team.

No amount of love, destiny, resources, compatibility, or compromise can make up for not having this pre-requisite shift in mindset. For our marriages to survive and thrive - whether to our soulmate or not - we have to believe it’s better together.

Conflict resolution can be baked into the design of our teams, families

In hindsight, approaching organizational life - whether it’s in our family, marriage, our work, or our community groups - with the expectation that we’ll have conflict is so obviously a good idea. If we’re intentional, we can design conflict resolution into our routines and make our relationships and teams stronger because of it.

In our family, there are no small lies.

So when our older son (Bo) lied about knowing where our younger son’s (Myles) favorite-toy-of-the-week was, we didn’t take it lightly. He went to “the step” where I directed him to stay for 10 minutes.

“Think about the reason why you lied. I want to know why. We’re going to talk about it over lunch.”

“But papa…”

“You’re a good kid. But lying is unacceptable in this family. We’re going to talk about it over lunch.”

It turns out, Myles did not treat Bo well the previous night. The two of them recently started sharing a room (which they love and they get along great), and Myles was talking loudly and preventing his big brother from sleeping.

Bo, now four, was not happy about this. And even though Bo loves his little brother dearly - they’re best buds, thank goodness - his frustration manifested by taunting Myles about the toy keys, and lying about knowing where they were.

As we talked over lunch, the real problem became clear, lying was merely a symptom. Bo was angry about being mistreated by his little brother. What our lunch became was not an interrogation about why Bo lied, but a expression of feelings and reconciliation between brothers. Our scene was roughly like this:

“Bo, I think I understand why you lied about the toy keys. When someone does something we don’t like, we have to talk to them about it. I know it’s hard. Let me help you work this out with Myles. Could you tell Myles how you felt?”

“Sad.”

“Why?”

“Because you were talking loud and I couldn’t sleep.”

“What would you like him to do to make it right with you?”

“Don’t bother me when I’m trying to sleep, Myles.”

“Can you both live with this and say sorry?”

“Okaaayy…”

Which got me to thinking - this happens in organizational life all the time.

Intentionally or not, we get into conflicts with others. More often than not, the conflict brews until it spills out into an act of aggression. Rarely, in our organizational worlds, is conflict handled openly or proactively.

It’s understandable why it plays out this way Conflict is hard. Admittedly, my default - like that of most humans - is to avoid dealing with all but the most egregious of conflicts and letting things resolve on their own. Stopping everything to say, “hey, I’ve got a problem” is incredibly uncomfortable and difficult. Basically nobody likes being that guy.

It’s MUCH easier to pretend everything is fine, even though it’s usually a bad choice over the long-run. This tendency is unsurprising; it’s well understood that humans prefer to avoid short term pain, even if it means missing out on long-term gain.

But, we can design our organization’s practices to manage this cognitive bias. We can build pressure release valves into our routine, where it’s expected that we talk about conflict because we acknowledge up front that conflict is going to occur.

In our family, we’re experimenting with our dinner routine, for example. We shared with our kids that we’ll take a few minutes at the beginning of our meal to talk about what we appreciated about other members of the family, and share any issues that we’re having.

We had a moment like this with our kids:

“We all make mistakes, boys, because we’re all human. It’s expected. We’re going to talk about what’s bothering us before we get really sad and angry with each other.”

In hindsight, approaching organizational life - whether it’s in our family, marriage, our work, or our community groups - with the expectation that we’ll have conflict is so obviously a good idea. Conflict doesn’t have to be a bug, it can be a feature, so to speak. If we’re intentional, we can design conflict resolution into our routines and make our relationships and teams stronger because of it.

I didn’t realize it, but this design principle has been part of my organizational life already. The temperature check my wife and I do every Sunday is centered around it.

Even my college fraternity’s chapter meetings tapped into this idea of designing for peace. The last agenda item before adjournment was “Remarks and Criticism”, where everyone in the entire room, even if a hundred brother were present, had the chance to air a grievance or was required to verbally confirm they had nothing further to discuss.

The best part is, this “design” is free and really not that complicated. It could easily be applied in many ways to our existing routines:

Might we start every monthly program update by asking everyone, including the executives, to share their shoutouts and their biggest frustration?

Might every 1-1 with our direct reports have a standing item of “time reserved to squash beefs”?

Might part of our mid-year performance review script be a structured conversation using the template, I felt _______, when _________, and I’d like to make it right by _______?

Might the closing item of every congressional session be a open forum to apologize for conduct during the previous period and reconcile?

It might be hard to actually start behaving in this way (again, we’re human), but designing for peace is not complicated.

If you have a team or organizational practice that “designs” for peace and conflict resolution, please do share it in the comments. If you prefer to be anonymous, send me a direct message and I’ll post it on your behalf.

Sharing different practices that have worked will make organizational life better for all of us.

Clear, shared, expectations: in projects and parenting

My wife made a brilliant parenting move this week.

Our older son is 3, and we’re trying to work on table manners with him. At least 5 days a week we have been getting into some sort of tussle with him over playing with his food, chewing with his mouth open, or deliberately making a mess. Mealtime has been the most common trigger of friction between us all.

And the other day I asked Robyn what she wanted to do, and she calmly replied, “I have a plan.”

What she did was simple and immediately effective. When we were serving the next meal, she set expectations for our son as she was putting down his plate. “The expectation is that we eat Cheerios with a spoon, blueberries you can eat with your hands.” And on she went about sitting down properly and what can be dipped and what cannot.

Her plan of setting clear expectations, in advance, worked immediately. It was a master stroke.

—

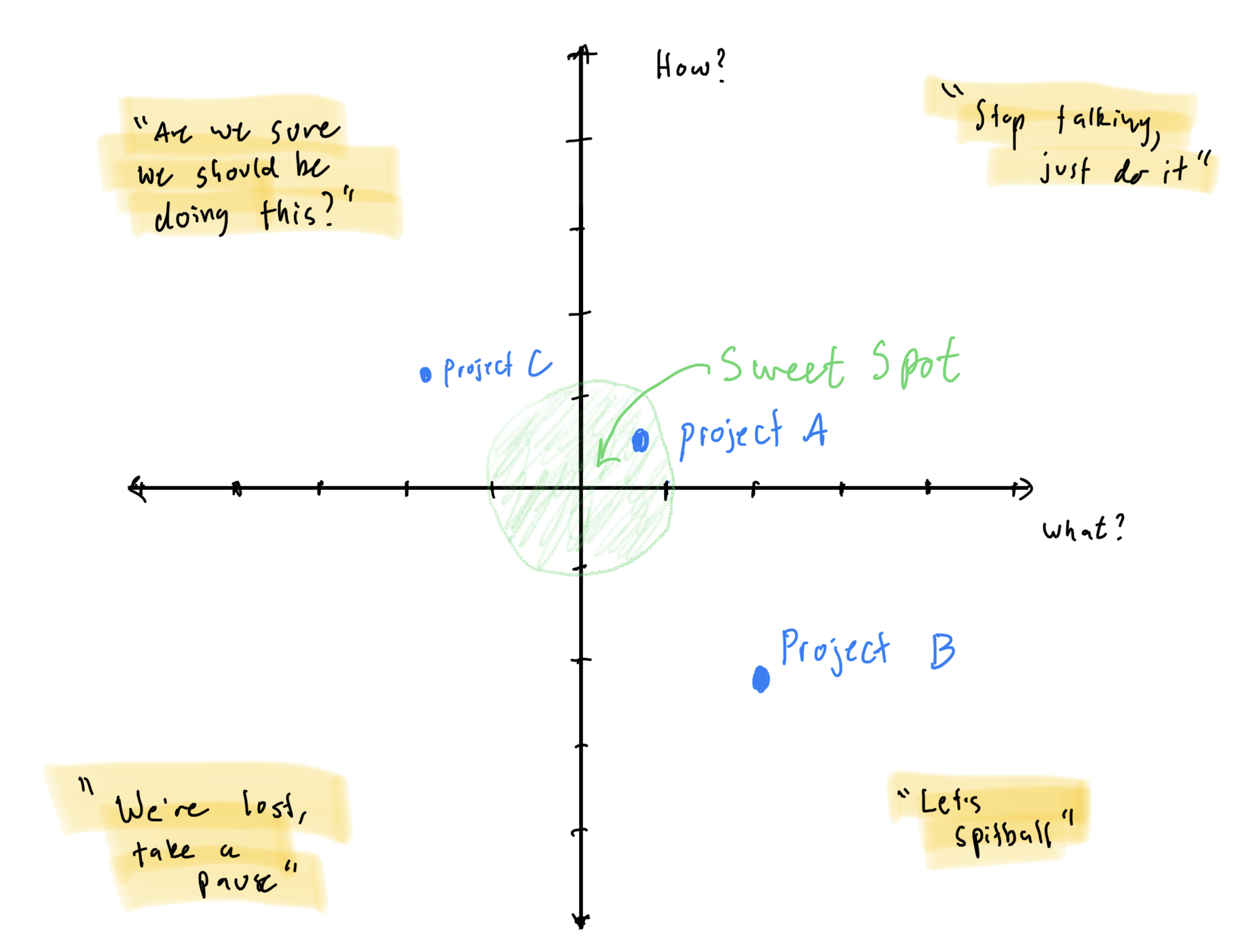

My work colleagues and I have been experimenting with approaches to clarify expectations, too. Instead of doing a weekly check-in with a traditional project board, we made a “why-what-how” board.

Here’s a representation of what our board (which is just a slide in PowerPoint) looks like:

What we do each week is re-score and re-plot our projects on this chart together. The goal of this exercise is to ensure the project is in the sweet spot of clear, shared, expectations.

The x-axis is the what. We make sure we understand what the intended outcome of the project is. Do we understand the deliverables? Do we understand what success looks like and what result we are trying to create? If the value is left of the origin it means the what isn’t clear enough. If the value is to the right of the origin, it means we are over analyzing the intended outcome and/or talking about it more than we need to.

The y-axis is the how. We make sure we understand the steps we need to take to achieve the intended outcome of the project. Do we understand the major milestones and next steps? Do we have a plan for how we’ll actually get the deliverables and analyses done? Do we understand the roadblocks ahead? If the value is below the origin, it means the how isn’t clear enough. If the value is above the origin, it means we’re micromanaging the project or getting too prescriptive about how it should be done.

We ask ourselves each week, usually during our Monday morning check-in, where are we at for each project. If we’re outside of the sweet spot, we spend some time clarifying the what, the how, or both.

Each quadrant, conveniently, has a nicely fitting heuristic which gives us a nudge on how to get back to the sweet spot:

High how, high what: we are talking too much. Let’s just take action.

Low how, high what: we understand what we’re trying to accomplish, but need to talk about how we get there. Let’s spitball and figure it out.

Low how, low what: we’re totally lost. We need to take a pause, reset and understand everything clearly where we are. This is the quadrant where the project is at risk and we have to dig out immediately.

High how, low what: this is the we might be wasting our time quadrant. If we don’t know what we’re trying to accomplish, even if we nail the project tactically, are we even solving the correct problem? We need to clarify the what (usually by escalating to the sponsor) or end the project.

What’s not plotted on the graph, but in the data table that powers the graph, are a few other elements: the why and who and the immediate next step.

The why and who has been a recent addition to our board, that we added a few weeks after trying this out for the first time. This value is the motivation for the project. Why does it matter, who is it for, what positive impact is this project in service of, why should anyone care about it? We think about our who as one of four general parties, that are applicable, honestly, to any organization. Any project has to ultimately impact at least one of these stakeholders in a big way to have a compelling why:

Our customer

Our owners or shareholders

Our colleagues

Our society or the communities in which we operate

If we can’t think of a compelling reason why what we’re doing matters to at least one of these four stakeholders, why are we even working on this project? We push ourselves to understand why, for our own motivation and to ensure we’re not doing something that doesn’t actually matter.

We also ensure everyone knows what the immediate next step is. If that’s not clear we establish it right there so there’s no reason we can’t take action right after our meeting.

Our team only started experimenting with this since the beginning of the year, but I’ve been finding it to be much more helpful than a traditional project board where the conversation revolves around the ambiguous concept of “status” and “accountability”.

Instead of checking our “status” non-specifically, and being reactive to a project that is “off-track”, we ensure that everyone on the team has clear, shared, expectations on each project, and we chip away at getting into the sweet spot of clarity on a weekly basis. By using this approach, we end up teasing out problems before they become large. Because after all, how often do projects get off-track if the why, what, and how of the project are clear to everyone, all the time? Rarely.

This approach is also much less autocratic than a traditional project board. Instead of the “manager” being dictatorial and projecting authority, this process feels much more democratic and equal, relatively at least. We all are working through the why, what, and the how together and even though one of us on the team is the titular “manager”, it feels more like we’re all on equal footing.

This is a good thing because everyone is more able to speak up, ask questions freely, and bring their talents forward to benefit the team and the people we’re serving. It’s less of an exercise where everyone is afraid of not having hit their milestones and therefore trying to tap dance around the status of the project.

There is of course a time and place for “status” and “accountability”. Of course, deadlines and results matter and we have to hit those. But what I’ve found so far is that by having clear, shared, expectations we are in a perpetual state of forward motion. We hit our deadlines as a natural consequence of having clarity. As is often said, but no less true, an ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure.

As is usually the case, what my wife and I are learning as parents is incredibly relevant to what we are learning about management and leadership. In this case the lesson is simple: clear, shared, expectations lead to better results (and less strife).