Exponential Talent Development

What would have to be true for every person to contribute 100% of their potential to the world?

Most of us have a HUGE gap between the impact we actually make and what we are capable of.

Asking myself (and my teammates) this question helps me put it in perspective: How would you rate yourself on a scale from 1 to 100?

A 100 represents making the highest possible impact that your talent and potential allow.

A 1 represents completely wasting the opportunity to positively contribute to the world.

I think most of us, myself included, are much lower on this scale than we realize—maybe a 20 or 30 at best. This realization begs the question: Why is there such a discrepancy, and what can we do about it?

In my experience, there are three reasons we leave vast amounts of our talent and potential untouched. First, we may never be challenged enough to use it. Second, we're not in the right contexts to let our strengths shine. Third, we may not have the support we need to develop the untapped talent we possess.

If we were all fully auto-didactic, we’d have no problem. That's because an auto-didact can fully teach and develop themselves. But none of us are completely auto-didactic; we all need others' help to develop ourselves so that we make our fullest contributions.

Introducing Exponential Skills

The difficulty in fully developing ourselves and others is relevant in many contexts. In professional settings, we call this challenge "talent development." In family settings, it’s "parenting." In community spheres, it's "mentorship" in secular contexts and "faith formation" in spiritual ones. In all domains of our lives, fulfilling and contributing the totality of our potential to the world matters.

The question I like to ask to really push my thinking is: What would have to be true for everyone in the world to develop and contribute 100% of their potential? As I’ve reasoned through this, the only way we get to the point of the world contributing 100% of their talent is through an exponential feedback loop where the number of people helping others to grow and develop increases exponentially.

To make the jump to create a society with an exponential feedback loop for talent development, let me define some terms and introduce some concepts:

We are all contributors who bring our talent and potential to the world. Some of us contribute by making art, others by building bridges, creating knowledge, making cakes, or making decisions. In mathematical terms, think of this as a constant: c.

A coach is a contributor who also helps develop others. Coaches are a big deal because they help others close the gap between their potential and their contribution. Think of this as x(c), where x is the number of people a coach is able to develop.

A linear coach is a coach who also helps develop other people into coaches. Think of this as mx(c), where m is the number of other coaches the linear coach creates.

An exponential coach is a linear coach whose coaching tree goes on in perpetuity: the people I coach become coaches, and then those people create more coaches, and those people create more coaches, and so on. Think of this as (mx(c))^n, where n is the number of generations an exponential coach is able to influence the cycle of creating more coaches.

Visually, I think of it like this:

Barriers To Creating Exponential Coaches

To create exponential coaches, several significant challenges need addressing. These challenges revolve around how we internalize and transmit knowledge, and the intrinsic motivations behind our contributions.

Challenge 1: Recognition Gap — The further you get from a contributor, the less credit you get for your work. This recognition gap can demotivate those who do not see immediate returns on their efforts. Solution: To overcome this, we must cultivate inner motivation and focus on long-term impact rather than immediate recognition. Developing a sense of purpose that transcends acknowledgment allows leaders to dedicate themselves to creating a lineage of coaches, thus prioritizing legacy over accolades.

Challenge 2: Complex Idea Communication — For an idea to spread, the messenger must internalize it sufficiently to simplify and communicate it effectively. This requires a deep understanding of both the intellectual and emotional aspects of the idea. Solution: Coaches need to engage in profound introspection to grasp the nuances of their knowledge and experiences fully. This depth of understanding enables them to articulate these concepts clearly and simply, making them accessible and teachable.

Challenge 3: Teaching to Teach — Teaching others to teach is a complex task that involves not only passing on knowledge but also instilling the value and methodology of teaching itself. This requires a reflective understanding of one’s own teaching practices. Solution: Coaches should introspect on their teaching methods and motivations, understanding them deeply enough to convey their importance to others. This process ensures that the coaches they develop can, in turn, teach effectively, perpetuating a cycle of self-replication in coaching practices.

Mastering these challenges not only enhances our own potential but also multiplies our impact exponentially across our communities and industries.

Where Do We Even Start?

On a personal note, the person I call Nanna is not my grandmother by birth but rather by love; she's my father-in-law's mother. During a trip to England a few years ago, I asked her about the secret to a long and healthy life. Here are the highlights of what she said:

Make time for family, faith, and community.

Stay active; keep your body moving, whether it’s through dancing, walking a dog, or any other physical activity.

Find a way to express yourself—through music, art, writing, knitting, making movies, having a book club, or any other form—because expression is crucial to mental and emotional health.

That last imperative is so deeply intertwined with introspection. Isn’t expression just a word that means exploring our inner world and then sharing it outside of ourselves? We have to express to be sane and healthy.

I know this post is heady and meta. I’ve been thinking about this concept for months, and I’ve only just synthesized enough to share a muddy morsel of it. A fair question to ask is: Where, in the real world, do we even start?

For inspiration on where to start on our own journeys to become exponential coaches, we can take heed from Nanna. She was onto something.

To become an exponential coach, we have to introspect and express. And to introspect and express, we have to find a medium that works for us and allows us to explore our inner world. And once we find it, we have to just practice with that medium, over and over.

For me, that medium is writing. For others, it might be painting, photography, singing, or making pottery. For others still, it might be talking honestly with a good friend, praying, or starting a podcast.

The medium doesn’t really matter, as long as we just do it. As long as we take that time to introspect and express. That’s the first step we all can take to grow toward becoming exponential coaches. Expression is the first step to becoming an exponential coach.

Thank you teachers, for being the rain

Thank you, teachers, for everything you do and have done - for me, for our three sons, and for all children. We have all yearned for the rain to drench our gardens, and you have made it pour.

The job of a gardener, I’ve realized three years into our family’s adventure planting raised beds, is less about tending to the plants as it is tending to the soil.

Is it wet enough? Are there weeds leeching nutrients? Is it too wet? How should I rotate crops? Is it time for compost? Are insects eating the roots? As a gardener, making these decisions is core to the craft.

The plants will grow. The plants were born to grow, that’s their nature. But to thrive they require fertile soil. That’s essential. And as a home gardener, ensuring the soil’s fertility is my responsibility.

Gardening is not just a hobby I love, it’s also one of my favorite metaphors for raising children. The connection is beautifully exemplified by a German word for a group of children learning and growing: kinder garten.

The kids will grow, but they rely on us to provide them with fertile soil.

And so we do our best. We cultivate a nurturing environment, providing them with a warm and cozy bed to sleep in. We diligently weed out negative influences, ensuring their growth is not hindered. Just as we handle delicate plants and nurture the soil, we handle them with gentle care, aware of their tenderness. And of course, we try to root them in a family and community that radiates love onto them as the sun radiates sunshine

If we tend to the soil, the kids will thrive.

Well, almost. The kids will only flourish if we just add one more thing: rain.

Without rain, a garden cannot thrive. While individuals can irrigate a few plants during short periods without rainfall, gardeners like us can’t endure months or even weeks without rain. Especially under the intense conditions of summer heat and sun, our flowers and vegetables struggle to survive without rainfall. The rain is invaluable and irreplaceable.

As the rain comes and goes throughout the spring and summer, it saturates the entire garden bed, drenching the plants and the soil surrounding them. The sheer volume of rainwater is daunting to replicate through irrigation systems; attempting to match the scale of rainwater is financially burdensome. Moreover, rain possesses a gentle touch and a cooling effect. It nourishes the plants more effectively than tap water.

For all these reasons, rain is not something we merely hope for or ask for - rain is something we fervently pray for.

It's incredibly easy to overlook and take for granted the rain. It arrives and departs, quietly watering our garden when we least expect it. Rain can easily blend into the backdrop, becoming an unscheduled occurrence that simply happens as a part of nature's course.

When we harvest cherry tomatoes, basil, or bell peppers, a sense of pride and delight fills us as we revel in the fruits of our labor. The harvest brings immense satisfaction and a deep sense of pride, even if our family’s yield is modest and unassuming.

As we pick our cucumbers, pluck our spinach, or uproot our carrots, it rarely occurs to me to credit the rain. And yet, without the rain, our garden simply could not be.

In the lives of our children and within our communities, teachers serve ASC the rain. And by teachers, I mean a wide range of individuals. I mean the educators in elementary, middle, and high schools. I mean the pee-wee soccer coaches. I mean the Sunday school volunteers. I mean the college professors engaging in discussions on derivatives or the Platonic dialogues during office hours. I mean the early childhood educators who infuse dance parties into lessons on counting to ten and words beginning with the letter "A".

I mean the engineer moms, dads, aunts, and uncles who coach FIRST Robotics, or the recent English grads who dedicate their evenings to tutoring reading and writing. I mean the pastors and community outreach workers showin’ up on the block day in and day out. I mean the individuals running programs about health and nutrition out of their cars. I mean the retired neighbors on their porch who share stories of their world travels and become cherished bonus grandparents. I mean the police officers and accountants who serve as Big Brothers and Big Sisters despite having no obligation to do so.

I mean them all and more. These people, these teachers, are the rain.

They find a way to summon the skies and shower our kids with nourishing, life-giving rain. As a parent and a gardener nurturing the soil in which children are raised, I cannot replicate the rain that teachers provide. Without them, our children simply could not flourish.

Candidly, this is also a personal truth. I have greatly relied on and benefited from numerous teachers throughout my life. It has all come full circle for me as I've embraced the roles of both a parent and a gardener. Witnessing our children learn, grow, and thrive under the guidance of teachers has been a humbling revelation. I've come to realize that without teachers, my own growth and development would not have been possible. Without teachers, I simply would not be.

This time of year is brimming with graduations - whether they're from high schools, colleges, or even from Pre-K like our oldest just graduated from this weekend. Much like the bountiful harvest, it is a time for joyous celebration. Our gardens have yielded fruit, and we should take pride in our dedicated efforts.

But in this post, I also wish to honor all of the different types of teachers out there. They have been the gentle, nurturing rain - saturating the soil and fostering a fertile environment for our children to flourish.

Thank you, teachers, for everything you do and have done - for me, for our three sons, and for all children. We have all yearned for the rain to drench our gardens, and you have made it pour.

Photo by June Admiraal on Unsplash

Coaching Requires Dedicated, intensely Focused Time

The biggest error of coaching - not being intentional about it - can be avoided by dedicating real time to it.

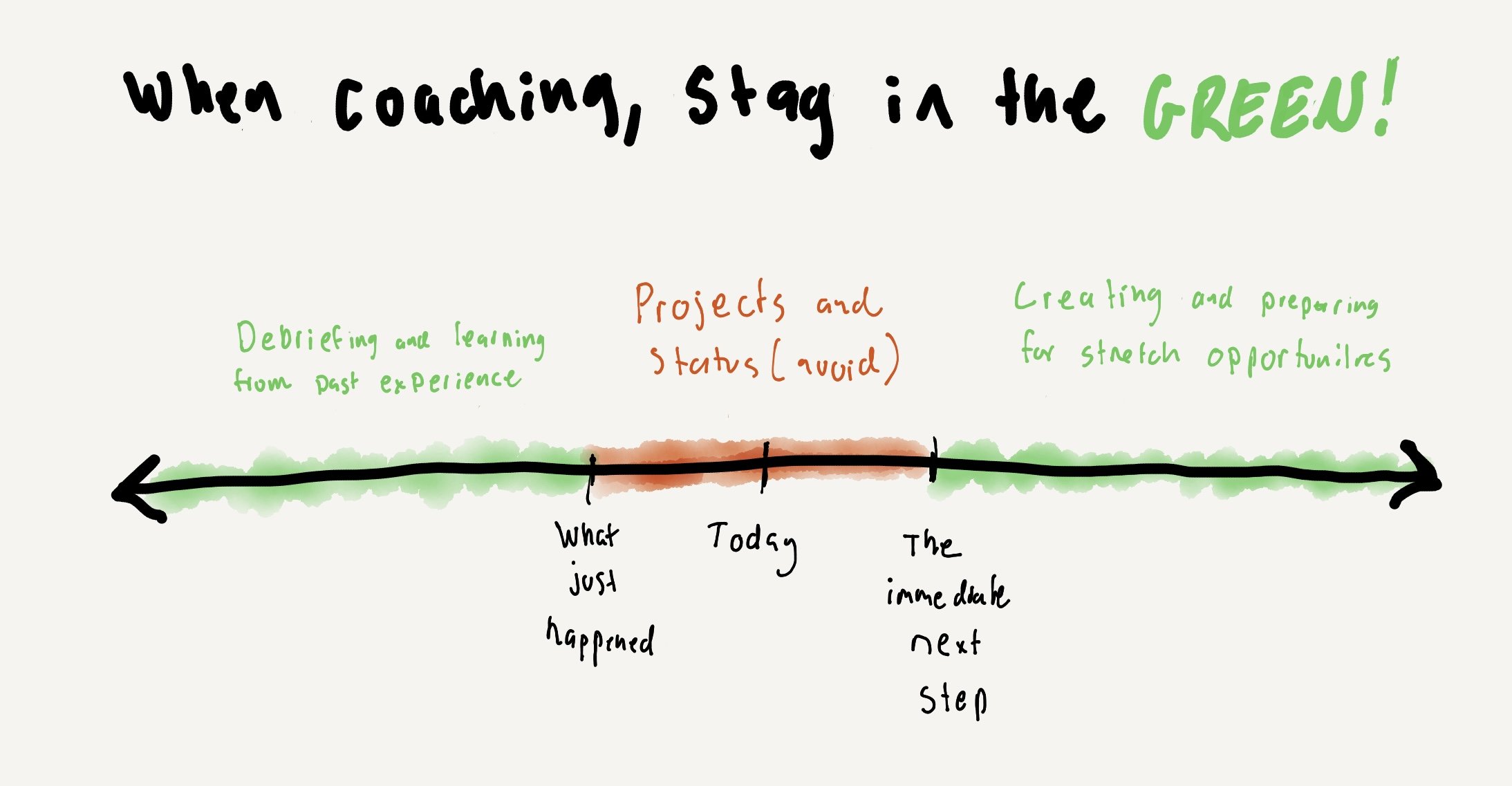

People develop faster when they are coached well, but coaching doesn’t happen without intent. To be a better coach, start with making actual “coaching time” that is intentional and intensely focused.

First, as a manager, we must dedicate one-to-one time with whomever we are trying to coach. 30 minutes per week, used well, is enough.

Second, that time can’t be about projects or status. It has to be spent on debriefing to glean learnings from past performance, or on how to create and prepare for future stretch opportunities.

Find a better way to manage status and project work than during a 1-1 and dedicate that time too and use it with intense focus. Personally, I like daily stand-ups from Agile/Scrum methodology and a once weekly full project review with the whole team.

Then, set a rule that during the dedicated time you will not talk about project status or the daily grind of work. If you dedicate time and hold firm to that rule, you’ll end up having a productive coaching conversation. Here are four questions that I’ve found work well to structure a 30-minute coaching conversation.

On a scale of 1 to 100, what percent of the impact you think you could be making are you actually making? (2-4 minutes)

Compared to last week, is your rate of growth accelerating, decelerating, or about the same? (2-4 minutes)

What do you want to talk about? (20-25 minutes)

What’s something I can do to help you feel respected and supported? (2-4 minutes)

This concept applies broadly: whether it’s coaching our team at work, our kids, our students, a volunteer group we’re part of, or co-coaching our marriage together with our partner, we must dedicate and focus the time. In my experience, the results of that dedicated time are exponential after just a few weeks.

When our kids have hard days

I want to remember that the goal of parenting is not avoiding my own sadness.

The first words he said to me, as he had the purple towel draped generously over his wet hair and entire frame, were,

“It was a hard day, Papa.”

And then he melted into me, and I, on one knee, wrapped my arms around him and started to rub his back - both to help him dry off and comfort him. And we just stayed there, hugging on the bathroom floor for awhile.

And that’s one of the saddest type of moments I think I’ve had - when you’re kid is just sad. And yes even at three years old and change, he can have hard days and recognize that those days were hard.

And it wasn’t even that I felt and explosive, caustic sadness, where you feel the sadness growing and pushing out from core to skin. Like a sadness that smolders into my limbs and mind, and makes them feel like burning.

It was a depleting sadness, where I started to feel my heart shrinking, my bones and muscles hollowing, and my face and skin starting to feel...transparent maybe. It was a sadness that made me feel like I was disappearing.

When your own children - the ones you have a covenant with God and the universe to take care of - are truly sad, it’s a feeling you want to pass as quickly as possible, and never want to have again.

And when I realized that I “never want to feel this way again”, I started to get these two primal-feeling urges.

First I wanted to “fix it”. And “fixing it” has two benefits. First, it just stops this horrible feeling of depleting sadness. Because if I fix it, my son isn’t sad anymore, and therefore I’m not sad anymore.

But also, if I were the one who failed my son somehow and caused him to fall into this genuine sadness, fixing it is my redemption. Fixing the sadness is what helps me to feel like I’m not to blame. Because if I’ve fixed the external problem causing his sadness - the problem wasn’t me, it was that thing. Fixing it gives me the illusion that I’m the hero in this story, not the villain.

But beyond wanting to fix it, there was a more insidious urge, that crept on me slowly, was to believe this falsehood of, “maybe he’s just not ready” or “maybe we need to protect him more”.

And the fuzzy logic of that urge is this: If my kid is sad, there’s something out there that he can’t handle yet. And if I hold him back from going back out there, he’s less likely to have a hard day. Then he won’t be sad. And then I won’t feel this depleting sadness either.

But the problem with both of these responses is that if I find a way to let myself off the hook, it also deprives him of the opportunity to grow, and muddle his way through his sadness. Our kids will have hard days, and those days will suck. And on those days, we have to bring our best selves as parents. Because that’s when our kids need us to guide them, and love them, and coach them, and encourage them. And, many of those times we won’t be good enough; we will fail as parents and coaches. And they will have to muddle through that sadness for a longer. And we will feel depleted for longer, too.

But, damn. From those hard days, and that sadness, comes strength and confidence for our kids. Once they muddle through sadness, they have one more datapoint to add to their model to remind them that they can do this, they can figure this out, they can be themselves, they can be at peace, and they can rise up and through adversity.

And even though my instinct is to help my sons avoid sadness, I cannot let that instinct win. Because that instinct is selfish. What that motive truly is, is me wanting to avoid that horrible, depleting sadness that comes when your kids are sad.

Because these kids will have hard days. They will be sad. And even though my instinct is to make it stop as quickly as possible, and to never let this happen to them ever again, I must resist that selfish urge to fix their problems for them.

What I really need to do is comfort them, encourage them, love them, and coach them, and show them that no matter what happens I will be with them in this foxhole of sadness until they find a way out, no matter what.

And that I will be there, and support them in a way that doesn’t deprive them of the chance to come out of it stronger, kinder, and wiser.

The Weekly Coaching Conversation

Coaching others is definitely the most important and rewarding part of my job. When I took on this responsibility, I worried: would I waste my colleagues’ talent? How do I help them grow consistently and quickly?

Here’s a summary of what I‘ve been experimenting with.

Experiment 1: Dedicate 30 minutes to coaching every week

I raided my father-in-law’s collection of old business books and grabbed one called The Weekly Coaching Conversation: A Business Fable About Taking Your Game and Your Team to the Next Level.

The idea in it is simple: schedule a dedicated block of 30 minutes every week with each person you’re responsible for coaching. I thought it was worth trying. As it turns out, it was. Providing support, feedback, and advice falls by the wayside if it’s not part of the weekly calendar - at least for me.

Experiment 2: Ask Direct Questions

We start each 30 minute weekly meeting the same way, with a version of these two questions:

On a scale of 1-100 how much of your talent did we utilize vs. waste this week?

This question is useful because it’s direct feedback from the person I’m trying to coach. I can get a sense of what they need. Most of the time, what is holding them back is either me, or something I can support them with, such as: more clarity on the mission, an introduction to a subject-matter expert, some time to spitball ideas, or just some space to explore. This is also a helpful question to ask, because when the person I’m coaching is excited and thriving, I get to ask them why, and do more of it.

What’s one way you’re better than the person you were last week?

This question is useful because it helps make on-the-job learning more explicit and concrete. We get to unpack results and really see tangible progress. Additionally, I get a sense of what the person I’m coaching cares about getting better at which allows me to tailor how I coach them.

Experiment 3: Stop controlling the agenda

At the beginning, I would suggest an agenda for our weekly coaching sessions. But over the course of 3-5 weeks, I transitioned responsibility for setting the agenda to the person I’m coaching. This works out better because we end up focusing our time on what matters to them, rather than what I think matters to them (which is good, because I’m usually wrong about what matters to them).

It also works out well because my colleagues are in the driver’s seat for their own development. And that fosters intrinsic motivation for them, which is really important for fueling real growth. I certainly raise issues if I see them, but it frees up my headspace and my time to be responsive to what they ask of me.

I still have a lot of improvement to do here, but I spend a lot less time talking and much more time asking questions and being a sounding board by letting go of control of the agenda. Which seems to work out better for my colleagues’ growth.

What I’m thinking about now (I haven’t figured it out) how do I know that my support is actually working, and leading to real growth and development?

—

I am absolutely determined to discover ways to stop wasting talent, in my immediate surroundings and across the organizational world. It’s a moral issue for me. And I figure a world with less wasted talent starts with me wasting less talent.

I’ll continue to share reflections on what I’m experimenting with so all of us that care about unlocking the potential of people and teams have an excuse to find and talk to each other.