How to Avoid Boondoggle Projects

Cut through project complexity with five essential questions that streamline focus and drive effective leadership, ensuring project success without the fluff.

I’ve spent too much of my life on absolute boondoggles of projects. Now, I know better.

To avoid boondoggle projects in any organization or team, these five questions must be clear to everyone (especially to me): who, what, to what end, why, and how.

Here they are:

Who are we serving? Answering this provides clarity on whose needs we really have to meet and who the judge of success and failure actually is. If we’re not clear on who is saying “thank you” at the end of all this, how can we do something magical for them?

To what end do we aspire? This clarifies what a successful mission looks like. The needle has to move on something; otherwise, why are we putting forth any effort?

What are we delivering? This clarifies the tangible thing we have to put in front of someone’s face or into their hands. If we’re not clear on what we’re building, aren’t we all just wasting our time?

Why does this matter? This clarifies the urgency and importance. If this doesn’t matter a lot, let’s respect ourselves enough to do something else that does.

How are we going to get from here to the end? This clarifies the process. If we don’t know how to get this done, will we ever finish?

Answering these five questions is the cheapest, simplest project charter you’ve ever had. If everyone on the team has the same answers to these questions, you’ll prevent the project from becoming a boondoggle.

If we’re part of leading a project, getting the team to clarity on these five questions is our job.

Clear, shared, expectations: in projects and parenting

My wife made a brilliant parenting move this week.

Our older son is 3, and we’re trying to work on table manners with him. At least 5 days a week we have been getting into some sort of tussle with him over playing with his food, chewing with his mouth open, or deliberately making a mess. Mealtime has been the most common trigger of friction between us all.

And the other day I asked Robyn what she wanted to do, and she calmly replied, “I have a plan.”

What she did was simple and immediately effective. When we were serving the next meal, she set expectations for our son as she was putting down his plate. “The expectation is that we eat Cheerios with a spoon, blueberries you can eat with your hands.” And on she went about sitting down properly and what can be dipped and what cannot.

Her plan of setting clear expectations, in advance, worked immediately. It was a master stroke.

—

My work colleagues and I have been experimenting with approaches to clarify expectations, too. Instead of doing a weekly check-in with a traditional project board, we made a “why-what-how” board.

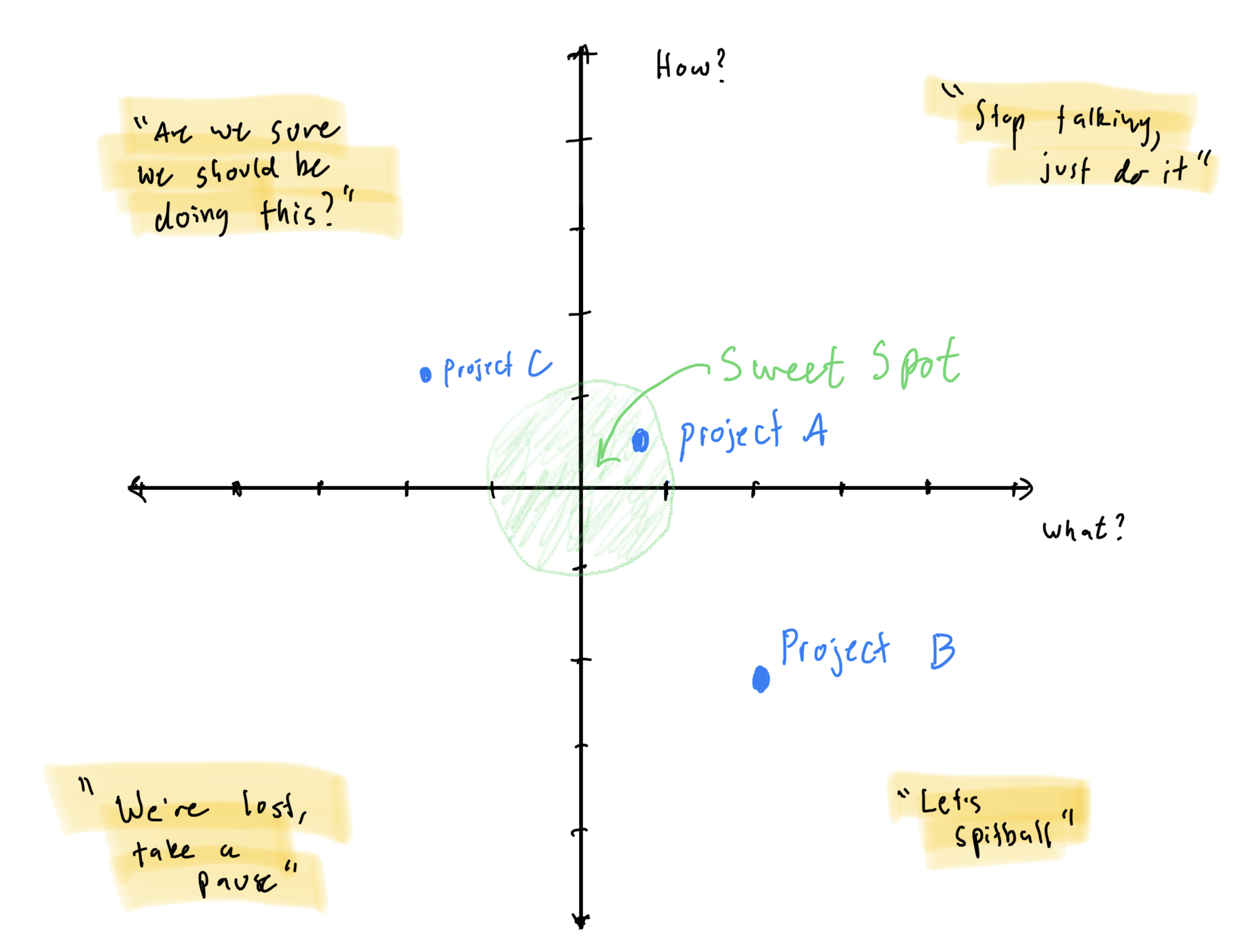

Here’s a representation of what our board (which is just a slide in PowerPoint) looks like:

What we do each week is re-score and re-plot our projects on this chart together. The goal of this exercise is to ensure the project is in the sweet spot of clear, shared, expectations.

The x-axis is the what. We make sure we understand what the intended outcome of the project is. Do we understand the deliverables? Do we understand what success looks like and what result we are trying to create? If the value is left of the origin it means the what isn’t clear enough. If the value is to the right of the origin, it means we are over analyzing the intended outcome and/or talking about it more than we need to.

The y-axis is the how. We make sure we understand the steps we need to take to achieve the intended outcome of the project. Do we understand the major milestones and next steps? Do we have a plan for how we’ll actually get the deliverables and analyses done? Do we understand the roadblocks ahead? If the value is below the origin, it means the how isn’t clear enough. If the value is above the origin, it means we’re micromanaging the project or getting too prescriptive about how it should be done.

We ask ourselves each week, usually during our Monday morning check-in, where are we at for each project. If we’re outside of the sweet spot, we spend some time clarifying the what, the how, or both.

Each quadrant, conveniently, has a nicely fitting heuristic which gives us a nudge on how to get back to the sweet spot:

High how, high what: we are talking too much. Let’s just take action.

Low how, high what: we understand what we’re trying to accomplish, but need to talk about how we get there. Let’s spitball and figure it out.

Low how, low what: we’re totally lost. We need to take a pause, reset and understand everything clearly where we are. This is the quadrant where the project is at risk and we have to dig out immediately.

High how, low what: this is the we might be wasting our time quadrant. If we don’t know what we’re trying to accomplish, even if we nail the project tactically, are we even solving the correct problem? We need to clarify the what (usually by escalating to the sponsor) or end the project.

What’s not plotted on the graph, but in the data table that powers the graph, are a few other elements: the why and who and the immediate next step.

The why and who has been a recent addition to our board, that we added a few weeks after trying this out for the first time. This value is the motivation for the project. Why does it matter, who is it for, what positive impact is this project in service of, why should anyone care about it? We think about our who as one of four general parties, that are applicable, honestly, to any organization. Any project has to ultimately impact at least one of these stakeholders in a big way to have a compelling why:

Our customer

Our owners or shareholders

Our colleagues

Our society or the communities in which we operate

If we can’t think of a compelling reason why what we’re doing matters to at least one of these four stakeholders, why are we even working on this project? We push ourselves to understand why, for our own motivation and to ensure we’re not doing something that doesn’t actually matter.

We also ensure everyone knows what the immediate next step is. If that’s not clear we establish it right there so there’s no reason we can’t take action right after our meeting.

Our team only started experimenting with this since the beginning of the year, but I’ve been finding it to be much more helpful than a traditional project board where the conversation revolves around the ambiguous concept of “status” and “accountability”.

Instead of checking our “status” non-specifically, and being reactive to a project that is “off-track”, we ensure that everyone on the team has clear, shared, expectations on each project, and we chip away at getting into the sweet spot of clarity on a weekly basis. By using this approach, we end up teasing out problems before they become large. Because after all, how often do projects get off-track if the why, what, and how of the project are clear to everyone, all the time? Rarely.

This approach is also much less autocratic than a traditional project board. Instead of the “manager” being dictatorial and projecting authority, this process feels much more democratic and equal, relatively at least. We all are working through the why, what, and the how together and even though one of us on the team is the titular “manager”, it feels more like we’re all on equal footing.

This is a good thing because everyone is more able to speak up, ask questions freely, and bring their talents forward to benefit the team and the people we’re serving. It’s less of an exercise where everyone is afraid of not having hit their milestones and therefore trying to tap dance around the status of the project.

There is of course a time and place for “status” and “accountability”. Of course, deadlines and results matter and we have to hit those. But what I’ve found so far is that by having clear, shared, expectations we are in a perpetual state of forward motion. We hit our deadlines as a natural consequence of having clarity. As is often said, but no less true, an ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure.

As is usually the case, what my wife and I are learning as parents is incredibly relevant to what we are learning about management and leadership. In this case the lesson is simple: clear, shared, expectations lead to better results (and less strife).